Eleanor Dark, c. 1940, photographed by Max Dupain. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

As the severity of Covid-19 restrictions have been dialled up and down over the past two years, one rule with a significant impact on my work as an independent writer remained a constant: university libraries largely barred physical access to non-students. This has been the case for most Sydney campuses at least and it’s only in early 2022 with the lifting of access restrictions at the main metropolitan university libraries that I am finally able to again enjoy the general borrowing rights that are admittedly patchy and uneven, at best. My paid alumni membership grants me limited privileges to download some scholarly articles that are more than five years old but no electronic books, which are now favoured over the acquisition of print titles. This decision to refuse library access to non-staff and students for such an extended period only compounded the paucity of resources and was out of step with the reopening timelines of most local and state libraries, as well as our National Library. It reflects a troubling introversion whereby tertiary institutions are increasingly focused upon catering to the discrete needs of students as clients, as distinct from embedding themselves more generously within the broader community.

Digital sources have always been central to my work but the recent limitations placed on library access has, unsurprisingly, led me to rely heavily on online research, prompting me to reflect critically upon its condition of ‘naturalized precarity,’ to borrow a phrase from cultural anthropologist Christopher Kelty.1 As open access has proliferated and archives are rapidly digitised, we have an unprecedented amount of digital content at our fingertips. Still, just as compiling bibliographies from print material has long involved mechanisms of judicious selection and discrimination to tame diverse sources into orderly lists, the digital realm is equally susceptible to biases – intentionally and incidentally. Unpicking the complexities of these biases is useful for understanding the barriers to accessing information that persist in the digital

world, and as a prompt to think about how this instability might also be harnessed productively to form new modes of research and creative activity.

*

Within academia, the arrival of open access is still the greatest disruptor to existing research paradigms. Open access allows research outputs to be distributed online without cost to the end user or institutional barriers. Open access’ capacity to attract detractors and advocates in equal measure is nothing short of remarkable. Proponents often become crusaders, linking it in a libertarian manner to a more profound type of creative license. The key attribute of this openness, says Martin Weller in The Battle for Open: how openness won and why it doesn’t feel like victory (2014), is ‘freedom – for individuals to access content, to reuse it in ways they see fit, to develop new methods of working and to take advantage of the opportunities the digital, networked world offers.’2 Creative Commons is arguably the most popular embodiment of this approach. Since its launch in 2001 the American not-for-profit has expanded to build a global network of resources available to legally share and build upon, reflecting a certain turn-of-the-millenium utopian ethos.

Open access’ logic is seductive, and its impact can be felt everywhere yet somehow this ubiquity hardly feels like a victory, a point Weller acknowledges in the subtitle of his book and a sentiment I share. Its more pernicious off-shoots include the explosion in predatory publishing practices, which in the scholarly world involves charging substantial author fees to publish articles in journals of questionable quality, as well as the growth in for-profit networking enterprises like academia. edu. I’m regularly spammed with invitations to contribute to pay-to-publish journals, solicitations that are easily recognisable to me as scams. However I’m not necessarily the intended audience, as these platforms are namely for STEM researchers who are required to publish their findings open access in the name of the public good. The truth is that quality publications require human labour and actual resources to produce, and inevitably someone must pay for this at some point. However beneficial open access appears on the surface, a deep dive into its machinations quickly reveals its exploitative pointy end. Then there’s the more prosaic matter of maintaining it. Librarians have quickly noted how the overall ‘unreliability of OA metadata and the difficulty in contacting OA publishers makes troubleshooting these resources more onerous.’3 These logistical shortcomings are hardly encouraging for the authors who have invested significant time and effort into taking this publishing route.

At the same time, digital poverty combined with the relatively high cost of home internet access and lagging digital infrastructure in Australia presents further barriers to equity in the shift to online research. The issue that perhaps weighs most heavily on my mind though, as both a creator of digital content and a consumer, is that of endurance, the capacity for content to be preserved online for the long term. I have seen many online journals and publications live very short lives, and have been troubled to see work disappear when funding dries up. Vanishing content, the authors of ‘Metadata and Open Access’ (2016) argue, is related to the broader fact that:

In the digital world, as has always been the case with written documents, copying is the way to resist annihilation, but it reaches new orders of magnitude. This point is all the more crucial that every digital document, when taken singly, is particularly fragile and vulnerable. Indeed, a tendency to evaporate allied to rapid technical obsolescence makes individual documents hard to preserve.4

Whether working with print or digital sources, research will always be haunted by absence. The slippages extend well beyond the material that we consciously exclude – not relevant, no room, ran out of time – to encompass the far greater amount of content that gets missed for all sorts of reasons. Content locked behind paywalls, omitted from results due to the commercialisation of search engines, misspelt metadata and poorly programmed algorithms are just a few of them. And all this before we even start to quantify the multitude of disappeared content, all the deleted and unarchived work that is gone and lost to view. The legitimacy and rigour of research is inherently tied to notions of comprehensiveness and yet as we navigate the precarious transition from print to digital, the knowledge gaps only grow wider.

*

At the beginning of 2021, a year into the pandemic and counting, I took stock of all these facts. I wondered whether I might design a writing project that could work more productively within the parameters of online research, rather than experiencing them as limits. Just as the authors of ‘Metadata and Open Access’ counterbalance their critique of the impermanence of digital content with affirmation for its generative capacity to ‘bring disparate but related documents together and create new research projects,’5 I began to think about how surrendering the desire to be exhaustive in my research might invite a freer approach, less constrained by conventional academic methodologies.

It was with this aim in mind that I formulated the premise of writing about two walks along the harbour foreshore in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, channelling these journeys through the lens of two formidable modernist authors, Eleanor Dark (1901–85) and Christina Stead (1902–83). The two Sydney-born women both lived in and drew upon these locales in their fictions. I resolved to freely mix primary and secondary, print and digital, scholarly and non-scholarly sources, resulting in an extended non-fiction essay composed over several months that I eventually printed in book format as Two Walks in late 2021. Revisiting a small cross-section of these sources provides an opportunity to reflect upon the research process and methodology, through which I came to appreciate not just the impossibility of separating print from digital but also the full extent of their codependency.

Brooks, Barbara and Clark, Judith. Eleanor Dark: A Writer’s Life. Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 1998.

First published in 1998, the biography Eleanor Dark: A Writer’s Life is long out-of-print but I was able to access a copy in between lockdowns at the State Library of New South Wales, which is also home to the Eleanor Dark papers. My initial instinct was to seek access to the papers, some thirty boxes of manuscripts, clippings, albums and diaries as well as pictorial material and, most intriguingly, locks of hair clipped from Dark and her family – ‘four generations of curls,’ according to the catalogue. Physical objects have an aura about them, and I felt the visceral pull of the archives. Yet I held back on the basis that this type of primary research would have set my project in an unintended direction, taking me away from my resolve to embrace digital sources and the freedom of a looser, open-ended approach.

Still, the tactility of the printed book and the pleasure of reading proved important in the early immersive stage of my research and Eleanor Dark: A Writer’s Life emerged as a pivotal text. Impressed by the generosity and attentiveness demonstrated by Barbara Brooks and Judith Clark in attending to the life and work of Eleanor Dark, I was emboldened to take a more personal and subjective route. The authors’ reliance on archival materials, including the papers held in the State Library’s collection, was also grounding. For as our exchanges become increasingly digital and ephemeral, I wondered at the fate of the literary biography in the years to come. Browsing the library’s photography holdings via the online catalogue, I noted that Dark was photographed by both Max Dupain and Olive Cotton: another pair of modernists. Dupain’s photograph was printed c.1940, around the time of the publication of Dark’s Sydney based fiction Waterway (1938). With a click of the mouse I downloaded Dupain’s photograph, filing it under ‘Eleanor Dark.’

Lidoff, Joan. Domestic Gothic: The Imagery of Anger, Christina Stead’s Man Who Loved Children.’ Studies in the Novel, 11.2 (Summer 1979): 201–15.

Between 1917 and 1928, the young Christina Stead lived at 14 Pacific Street, Watsons Bay, a large tumbledown weatherboard cottage, before sailing to England at the age of twenty-five. Stead’s former home provided the starting point for my second walk and the fact that the house is lightly fictionalised by Stead in The Man Who Loved Children (1940), deemed by many to be her masterpiece, led me to consider the influence of writers’ homes as another key theme of Two Walks. Underwhelmed by the plethora of cliched work on the topic, it was only when I discovered ‘Domestic Gothic: The Imagery of Anger in Christina Stead’s Man Who Loved Children,’ a startling essay by the late American scholar Joan Lidoff, that I was challenged to confront the unsettling psychic impact of the home in Stead’s work. Presenting an unflinching assessment of the oppressive nature of domesticity as it manifests in Stead’s masterly novel, Lidoff’s ‘Domestic Gothic’ acknowledges the disruptive impact of female rage in ways that resonate with current struggles.

Having accessed Lidoff’s essay from the academic database JSTOR, and noting that it first appeared in the prestigious literary journal Studies in the Novel, which is published by the John Hopkins University Press, I was compelled to acknowledge the importance of the scholarly publishing model. It was both thrilling and incredibly convenient to retrieve this pioneering work of scholarship via JSTOR. It is mostly due to the healthy investment by American and UK university presses in the printing and digitisation of their journals that essays like Lidoff’s remain accessible some forty years after their date of publication. Reflecting on the extent to which I reply upon these platforms, even with limited alumni access, produces an ambivalence that sums up my feelings about academia more broadly. On the one hand I remain committed to the notion that universities are one of the main incubators of original and even radical thinking in contemporary society. On the other, I must concede that the production and distribution of scholarly work is embedded within a system that is inherently elitist and exclusionary – a point that my two years of barred access to campus libraries has made painfully apparent.

‘Rest After Illness, Where the State Helps: Strickland Convalescent Home.’ Sunday Times, Sydney, 19 August 1917, 13.

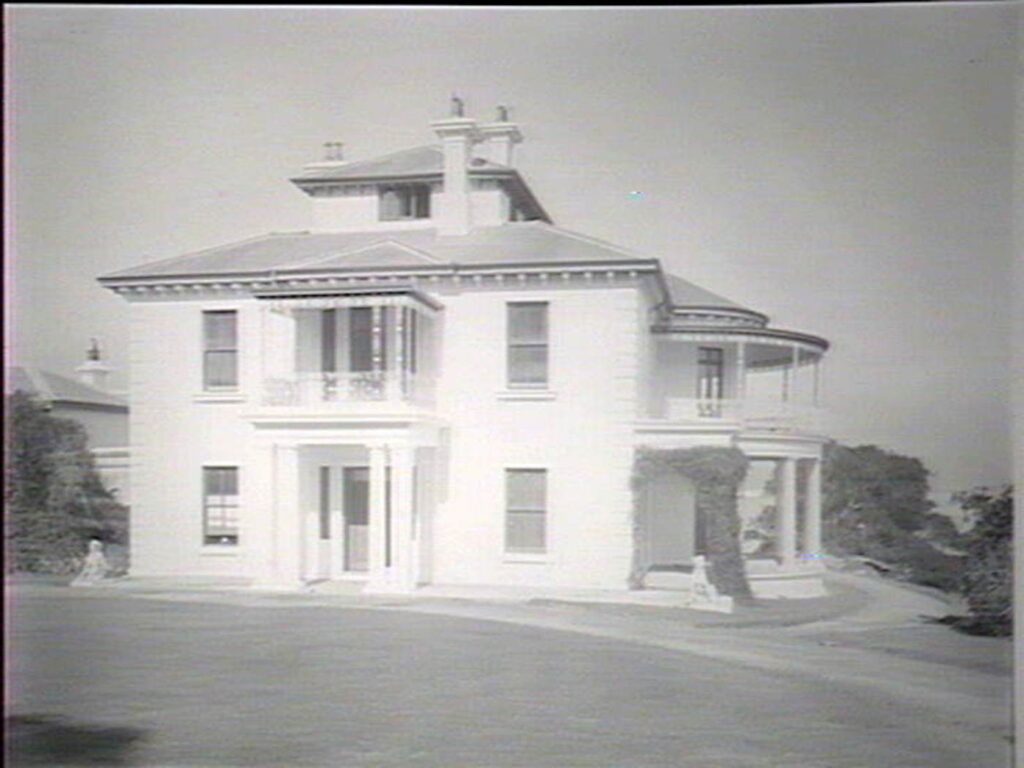

Formerly known as Carrara, Strickland House is a disused Victorian era mansion overlooking the water in Vaucluse and one of the key landmarks of the Hermitage Foreshore Walk. Eleanor Dark lived for a brief period in a nearby property, Benison, where she also convalesced after a kidney operation in the winter of 1935. This period of rest and recovery by Dark intersects with the former uses of Strickland House. Acquired by the New South Wales government in the early part of the twentieth century the building was first converted from a private residence into a convalescent home for women and later served as an aged care facility up until its closure in 1989. As I delved further into the biography of Eleanor Dark and the history of Strickland House, these parallel narratives of convalescence emerged as a key theme of my project.

Keen to understand more about Strickland House’s past life as a convalescent home I turned to the National Library of Australia’s online discovery tool, Trove, which yielded ready access to a plethora of digitised articles and press photography from the period. One article, ‘Rest After Illness,’ printed in 1917 in The Sunday Times caught my interest with its evocative description of the hospital’s landscaped setting complete with vegetable patch, dairy farm and eggs fetched from the poultry yard. The speed at which Trove allowed me to build up a picture of life at Strickland House more than a century ago was invigorating. Clicking through a set of blurred black and white photographs taken in the early days of Carrara, I was reminded of Gerhard Richter’s grey paintings. The connection between the photos and Richter triggered thoughts of the site’s complex history as a place of both gentle healing and latent trauma.

Trove’s name plays knowingly with the serendipitous nature

of online research, riffing off that joyous feeling of surprise discoveries that is perhaps not entirely appropriate for a national archive given the fundamental act of dispossession linked to stolen land at the heart of Australia’s history. Name aside, the tool functions as an important educational resource and is generally considered an exemplary model for collaborative digitisation projects. Since its launch in 2009, Trove has been caught up in culture wars and funding debates. However national interest in the site has rendered it a resource of ‘cultural and historical significance for all Australians’ and helped its cause. In 2020, the federal government committed an additional $8 million to the NLA to support its ongoing development.

Inevitably, the future of Trove circles back to issues of cost, value for money, sustainability and equity of access. These debates have neither disappeared nor become any simpler in the so-called free and open digital realm. When it came time to finalise my essay on the literary psycho geographies of Eleanor Dark and Christina Stead for printing, I checked over the bibliography for what felt like the nth time, fixing errant commas and full stops, searching anxiously for any errors before it was too late to correct them. While my freer engagement with digital sources had pushed my work in the new direction of creative non-fiction, sending it to print pulled me back into old habits: obsessing over accuracy, fearing flaws, feeling a sense of fidelity to the historical record. For in the end, our sources are paths for others to follow and whether retrieved or sent out to the world in print or digital, surely it still matters to nurture that quiet instinct to conserve, standing firm against the tide of virtual oblivion.

Ella Mudie is a writer and researcher

based in Sydney. Her work is focused on the geopolitics of the built environment and the representation of space more broadly in literature, photography and the visual arts. She received her PhD from the University of New South Wales in 2015.

No 2 (May 1994), 209.

14 Pacific Street, Watsons Bay. Former home of Christina Stead. Photo by Sardaka, Wiki Commons