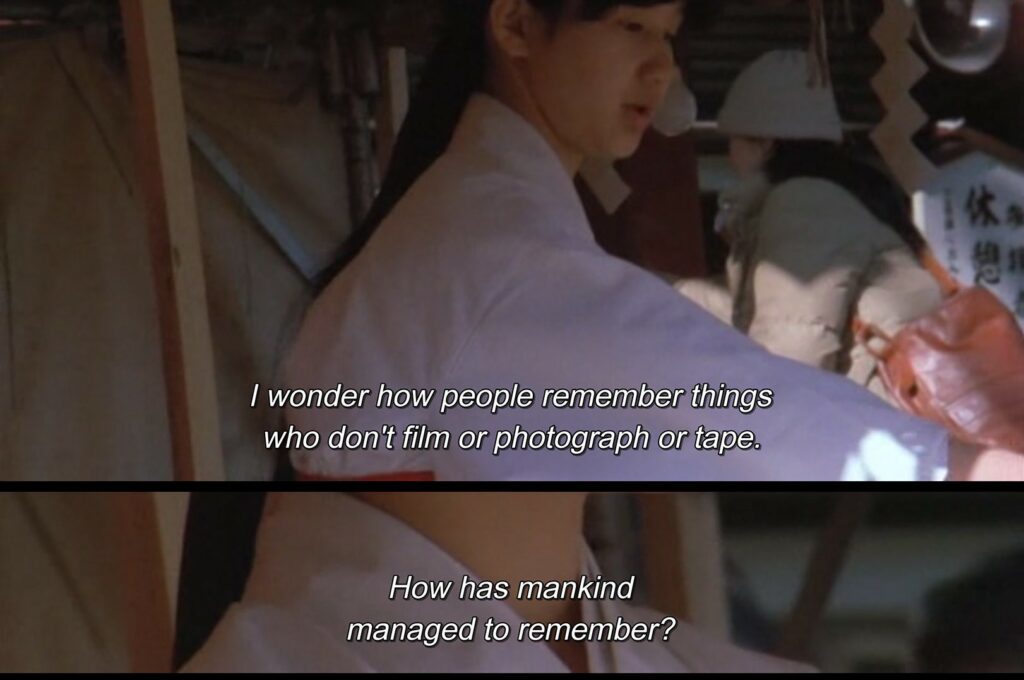

ED: Do you own a video camera?

– David Lynch, Lost Highway (1997)

RENEE MADISON: No. Fred hates them.

FRED MADISON: I like to remember things my own way.

ED: What do you mean by that?

FRED MADISON: How I remembered them. Not necessarily the way they happened.

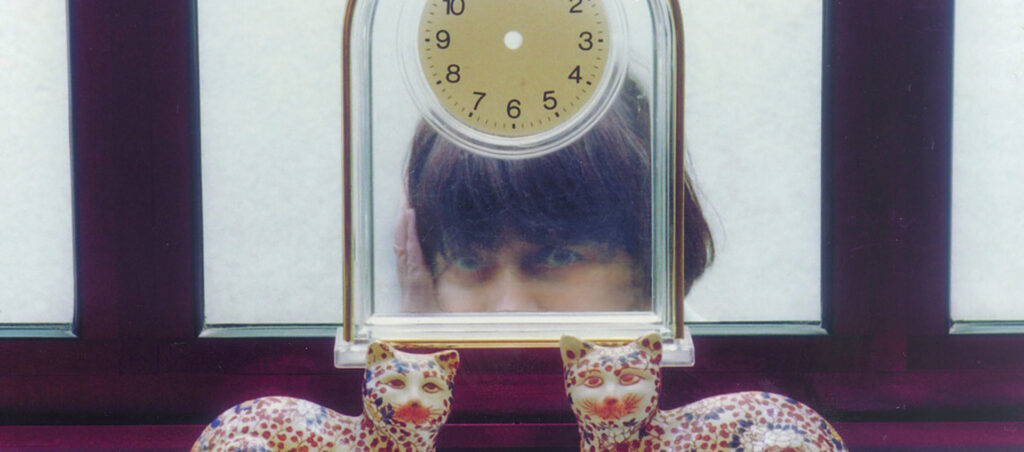

As a child I had a photographic memory. If only it were like that now, to be able to recall stories and dreams in crystalline detail. Maybe that isn’t important. The art I gravitate towards is elliptical, the photographs blurred, the films impressionistic. I create documents and lists to avoid forgetting. Inscribed or in assemblage, these records allow patterns and connections to surface.

Lists can be poems. Poems can be stories. Past, present and future tenses don’t matter when time isn’t linear.

A tiny praying mantis hanging in my father’s beard when he arrives home from the rubbish tip. The comforting rumble as his Volkswagen Kombi pulls into the driveway. Yellow tobacco stains on his fingers. The scent of my parents art studio: linseed oil, wood shavings, leather and clay. Decaying pages of antique books in the hallway library, stained like my father’s fingers. It’s called foxing: the mysterious, amber-coloured markings that appear on deteriorating paper. Memento mori.

Agnes Varda, The Gleaners and I (Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse) (film still), 2000,

I turn to libraries and bibliographies, seeking loose narrative threads hidden between the titles. Psychedelic philosopher, ethnobotanist, and psychonaut Terence McKenna’s extensive personal library, including his handwritten notes, burned to ashes twice – the first time while he was alive, the second after he’d departed to another plane of existence. His brother Dennis, having learned from the past, meticulously catalogued the second collection before it was destroyed. Yet, a catalogue is not a library. But a list can be a story.

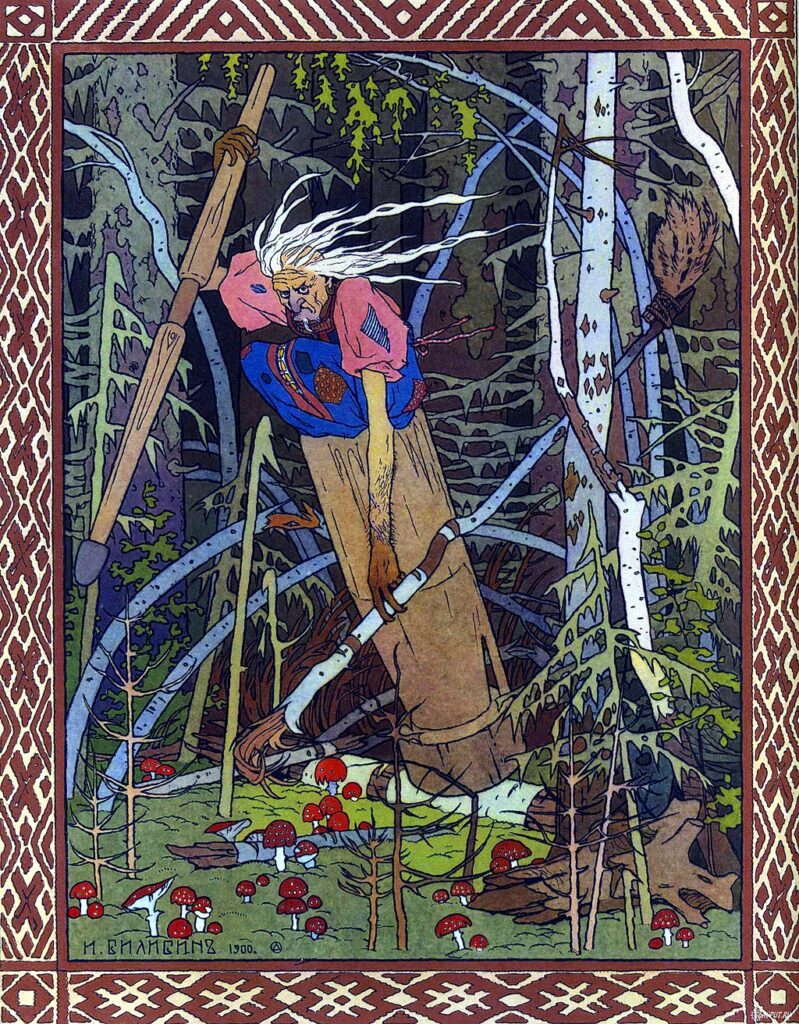

Ivan Bilibin, ‘Baba Yaga in her Mortar’ 1899, illustrations

McKenna, Terence. ‘Kathmandu Interlude.’

In True Hallucinations. New York: HarperCollins, 1989.

During my teenage years, with curiosity piqued by tales of my father’s psychedelic experiences in the 1970s, I sought anything that might allow an escape – imaginary or otherwise – from the stultifying culture of suburbia. In the novel True Hallucinations, Terence McKenna details his visionary adventures researching and experimenting with psychoactive plants. One chapter particularly galvanised my nascent fascination with altered states. It recalls a Tantric encounter on a rooftop in Nepal under the influence of DMT (the potent entheogen N,N-Dimethyltryptamine). He describes witnessing ‘... flowing everywhere, some sort of obsidian liquid, something dark and glittering, with colour and lights within it.’ McKenna interprets this substance as being a reflection of the surface of his own mind, suggesting the possibility that it was some kind of ‘translinguistic matter, the living opalescent excrescence of the alchemical abyss of hyperspace.’

As throughout his life’s work, the eloquent synaesthesia of McKenna’s articulation gives life to an otherwise alien and ineffable subjective experience. It is one example of countless cultural artefacts that have opened my mind to the mystical dimensions that exist beyond the limits of ordinary human consciousness.

Varda, Agnes, dir. The Gleaners and I

(Les Glaneurs et le Glaneuse). Cine-Tamaris, 2000.

My parents salvaged things that had been thrown away, restoring them, or using the materials to make art, toys, jewellery – anything of beauty to sell. This is how they survived and maintained a degree of resilience in the face of the hardship that often accompanies a creative life of integrity. When I first saw Agnes Varda’s essay documentary The Gleaners and I, I felt a sense of familiarity. Guided by the charming and inquisitive director, this meandering road trip celebrates the act of gleaning – of utilising that which has been discarded or overlooked. The film is a subtle critique of the excesses and dehumanisation of capitalism. Honest in her subjectivity, Varda makes things personal, steering the camera’s gaze on to herself as well as others. She records the signs of age on the surface of her hands, mould on the ceiling of her home which she likens to an abstract painting, heart-shaped potatoes she collects from a mountain of rejects dumped in a field by a supermarket chain. The Gleaners and I, through Varda’s sensitive lens, embodies the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which values imperfection and impermanence as an expression of nature and its cycles of life and death. She includes herself in a cast of social misfits – the artist as gleaner of poetry in the everyday.

Bilibin, Ivan,

‘Vasilisa the Beautiful at the Hut of Baba Yaga’, and ‘Baba Yaga in her Mortar,’ 1989, in Russian Folk Tales, 1899.

On windy days, our old stilted house creaks and sways among the treetops, threatening to wander away like Baba Yaga’s chicken- legged house in the Russian folk tale Vasilisa the Beautiful.

My childhood imagination was enchanted by Ivan Bilibin’s illustration of Vasilisa illuminating a night forest with a human skull lantern. She is surrounded by red mushrooms, some likely the entheogenic species, Amanita muscaria, traditionally used in shamanism throughout regions of the Far North.

While I admired Vasilisa’s bravery and beauty, I was most intrigued by Baba Yaga, a fearsome supernatural matriarch and forest dweller, depicted travelling in a large wooden mortar with a pestle and broom in each of her wiry hands. As a little girl, witch-like archetypes of folklore represented secret knowledge, wisdom, rebellion and the power of the outsider. They were, and continue to be, my heroines – proto-punks and feminist icons. My aunts in their youth shaved their heads and joined a coven. United via the internet, contemporary witches collectively cast monthly spells on Donald Trump during his presidency. The Australian environmental activist art collective, Dirt Witches, stage ritualised performance protests. Witches are everywhere, stealthily doing their work to disrupt and undermine hegemony.

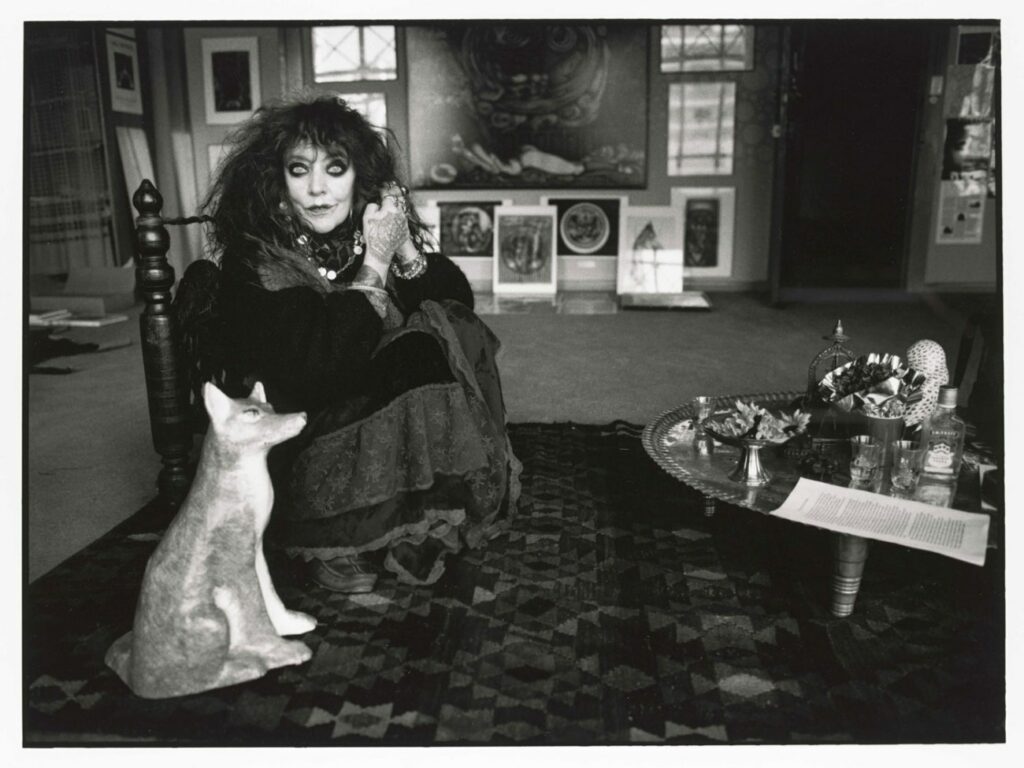

Vali Myers, Blue Fox, 1972–74,

Chinese ink, watercolour, gouache and gold leaf on paper, 39.2 x 30.4 cm.

Years ago, at the golden hour in a Melbourne laneway, I recognised the distinctive flame-coloured hair, pale eyes and face tattoos of Australian artist Vali Myers. It was like catching a glimpse of one of the wild creatures in her paintings. She was nicknamed ‘The Witch of Positano’ while living in a valley near Italy’s Amalfi Coast with an extended family of animal companions including owls, foxes, frogs and snakes.

Liz Ham, Vali Myers in her studio in the Nicholas Building,1997, gelatin silver photograph

Vali Myers, Blue Fox, 1972–74, pen, black ink, watercolour, tempera and gold leaf on paper

After her passing, I visited Myers’ studio on an upper level of Melbourne’s historic Nicholas Building. Home to hundreds of artists over the decades, the 1926 building is now under threat of redevelopment. Overlooking the Yarra River, Myers’ corner studio was a bohemian den with candy pink walls, flokati rugs and totemic objects, the walls and floors adorned with her intricate work, hand written diaries and personal photographs.

Her self-portrait, Blue Fox, channels hallucinatory Baba Yaga energy as the artist merges with a fox, her meditative gaze downturned while the fox stares resolutely to meet the viewer. Two otherworldly beings appear below and above her face like psychic gargoyles. Like much of Myers’ art, the work signifies a profound and non-hierarchical relationship to multispecies, as more-than-human kindred spirits and guides.

Meoto Iwa, n.d.

One summer I travelled to Yakushima, a circular, mountainous island in southern Japan, to help an artist friend film a solar eclipse. We soon learned that mountains form clouds, clouds make rain and summer is the time of monsoons. While disastrous for our mission, it imbued the landscape with an atmospheric elemental drama. On Yakushima the animist beliefs of Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion are palpable. Wild deer and monkeys traverse the winding road that circumnavigates the island, recognised for its ancient, mossy forests inhabited by revered Yakusugi, gnarly cedar trees aged over a thousand years. One such forest, Shiratani Unsuikyo Ravine, is said to be an inspiration for Hayao Miyazaki’s animated film Princess Mononoke (1997).

On Yakushima’s cliffs we came across a small stone yorishiro – an object designated to attract nature spirits (kami). Dedicated to Ebisu, the deity of fishing, fortune and things that drift ashore from the sea, it was accompanied by a beer can offering and draped with a shimenawa, traditional braided rope used for ritual purification. One of Japan’s most striking yorishiro is Meoto Iwa (‘Wedded Rocks’), two geological formations situated in the sea of Ise, Mie. Inhabited by the Shinto creator spirits Izanagi and Izanami, the rocks are joined by an immense shimenawa weighing around a tonne, a gesture that is ceremonially renewed three times a year as the rice straw is gradually eroded.

Veneration for the panpsychism of natural forms echoes through animist cultures. The Zen Buddhist gardener takes guidance from rocks as to their placement in a garden’s composition and rakes gravel daily in patterns resembling moving water. Creative practices involving slowness, duration, repetition, deep listening and mindfulness can radically transform our perception and understanding of the world around us.

Tadao Ando, Chichu Art Museum, 2004.

Tadao Ando and James Turrell, Minamidera

James Turrell, Backside of the Moon, 1999.

The immutable dance of celestial bodies and weather patterns

is a grand reminder of humility. On a remote headland as the eclipse approached, a lone group of Buddhist monks chanted in the torrential rain. At the decisive moment, the overcast sky and sea turned a strange shade of grey and the monkeys and birds in the forest fell silent. My friend, whose elegant, deeply considered ecological art practice I greatly admire, lay in a puddle in the downpour, laughing.

I hitchhiked around Japan for a couple of months. The hills of the art island Naoshima, in the Seto Inland Sea, are embedded with an underground museum designed by minimalist architect Tadao Ando to house major works by Claude Monet, Walter De Maria and James Turrell. The museum’s structure responds to nature, accommodating the circadian and seasonal movement of sunlight to interact with the art and interior spaces. Mastery of light and shadow is common ground to architecture, cinematography and photography. It is uniquely elevated and refined in Japanese aesthetics, incorporating great subtlety and restraint, as detailed in Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s essay, In Praise of Shadows (1993).

Across the island, a small fishing village has been transformed by installations created inside and amidst the traditional residential houses. With a small crowd, I entered a windowless building known as Minamidera, created by Ando and artist James Turrell to accommodate the latter’s work. Guided into a pitch-dark room, we were advised the experience would last 15 minutes and to feel our way along the wall. Disoriented in the warm space, anchored only by its boundary, I wondered what to do. It was bewildering yet hypnotic. After around ten minutes had passed, a very faint blue glow began to appear and a guide announced that we could now wander around the space. Subtle amber illumination crept in glacially at the edges of the blue, which now resembled a cinema screen. At some point it became apparent that nothing in the room had changed other than the ability to see in the dark. Through sensory deprivation, duration, light and colour, Turrell’s installation is mind altering, eliciting subtle aspects of the self through a process of physiological metamorphosis.

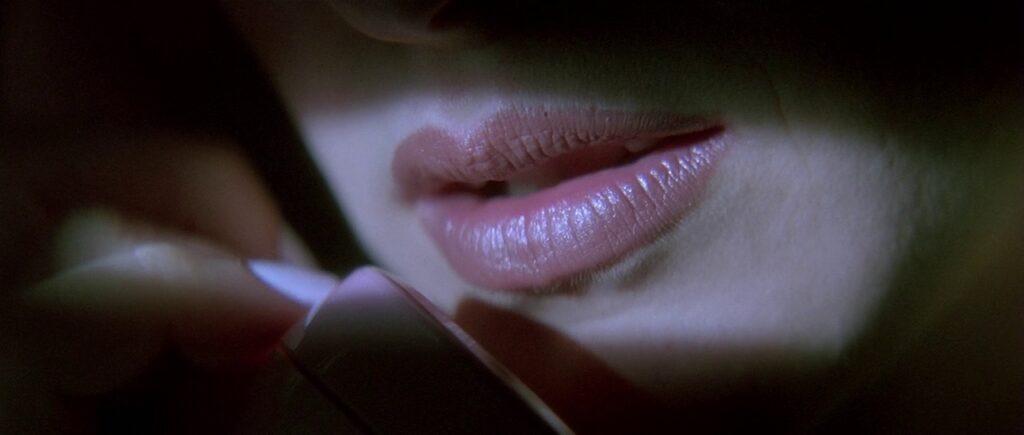

David Lynch, Lost Highway (film still), 1997.

Tsai Ming-Liang, The Deserted (virtual reality film still), 2017

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Memoria (film still), 2021

Lynch, David, dir. Lost Highway. Ciby 2000, 1997.

Lost Highway is David Lynch’s split psyche/parallel reality neo-noir prototype before it was reconfigured in Mulholland Drive (2001) with the glamour and decay of old Hollywood. Referencing the Hitchcock classic Vertigo (1958), angled through a more sinister prism, the film is a study in duality and psychosis. It reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly (1977) in which the protagonist, working as an undercover narcotics agent, gradually loses the ability to distinguish his real identity.

Lost Highway exemplifies the fetishist nightmare/dream logic that Lynch’s art tends to dwell in. The story is premised on the violence of possessive, paranoid masculine ego. Increasingly fragmented scenes that unfold between flashes of abject horror are a calculated seduction. An extreme closeup of Patricia Arquette’s lips speaking on the phone. Pools of lamplight illuminating minimalist architecture and mid-century furniture. A menacing encounter with a ghoulish man who claims to be in two places at once. The glint of metallic blue painted fingernails. A house fire in reverse. David Bowie’s sad, lilting voice singing ‘I’m deranged’ over footage of a road at night, illuminated by the headlights of a speeding car. And always the lurking dread of a world corrupted beyond control. The aesthetic sensuality of these compositions builds a psychological terrain that has no escape, only an endless cycle of memory, obsession and elusive objects of desire.

Ming-Liang, Tsai, dir. The Deserted. HTC Virtual Reality Content Centre with Jaunt China, 2017.

Tsai Ming-Liang’s excursion into virtual reality brings slow cinema to an immersive sensory experience, blurring distinctions between waking, dream and memory. Ming-Liang’s oeuvre is frequented by long static shots, minimal to non-existent dialogue and narrative, and the use of art design, sound and lighting to create atmospheric set pieces that act as extensions of his characters’ inner emotional lives. The Deserted moves through several scenes located among the ruins of an abandoned concrete housing block, surrounded by overgrown tropical forest. It centres on a man, recovering from illness in a dank, cave-like apartment, while the ghost of his mother cooks in the kitchen and a fish swims around a translucent plastic bathtub. Corporeal ailment in The Deserted is a manifestation of loneliness, melancholy, grief and regret as the individual is tethered to the past, caught in overlapping timelines and unable to fully exist in the present. Eventually, the body heals as turmoil is resolved.

Windows without panes bring the viewer into direct contact with the elements. The dissolution of boundaries – between interior and exterior, human and the supernatural – is simultaneously unsettling and tranquil, oppressive and cathartic. Heavy rainfall slowly builds to a deluge. Pivoting my disembodied gaze to the floor below, I watch the water pool until the room begins to flood. The enveloping sound design, combined with the way the VR positions the viewer weightlessly like another spirit haunting the scenes, creates an overwhelming feeling of being inside not only the character’s universe but also their experience of it.

Weerasethakul, Apichatpong, dir. Memoria. Sovereign Films, 2021.

Sound is a central character in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria. In its various guises, it is both a protagonist and antagonist. Another film artist distinguished for cryptic, slow cinema in which memories, dreams and reality merge, Weerasethakul’s somnambulant work often draws on animist folklore, investing the more-than-human with agency and presence. Everything has a spirit, even sound.

Filmed in Colombia with British actor Tilda Swinton, Memoria – Weerasethakul’s first film made outside Thailand – was inspired by his own experience with a hypnagogic sleep disorder known as ‘exploding head syndrome’. The story concerns a Scottish orchid grower living in Medellín who is searching to understand an increasingly loud banging sound that perpetually disturbs her. She engages a sound engineer to replicate the effect in a production studio. Through language and technology they attempt to translate what exists in her mind, finally arriving at an uncanny, heavy reverberation: primal, foreboding and difficult to locate as human, metal or anything else. The self-reflexive scene – and the entire film – demonstrates the potency and nuances of the auditory experience and its capacity to conjure a range of abstract and unconscious emotions we can barely comprehend. In Memoria sound isn’t just a metaphor for anamnesis, it’s a mysterious, shapeshifting vessel that carries meaning, history and perhaps time itself.

Shiga, Lieko, Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2008–12, 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT8), Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2015–16.

I returned to Japan to complete an art residency in a small mountain village that once thrived from the sale of greenschist and white quartz monoliths extracted from the river that flows through it. These stones were highly prized in traditional garden design, but as demand declined the population dwindled, and many of the town’s old buildings were abandoned. In this ghost town – whose name means ‘demon or ogre stone’ – I learned about folkloric supernatural beings called yokai. A local told me about the concept of ‘tasogare’, which refers to the threshold of evening as the last light fades and you can no longer discern if the figure approaching you is human. Every night for six weeks, as the sun set, I explored the town’s empty streets and its rural surrounds on a rickety bicycle, my camera gear in a backpack, searching for strange or sublime visions and sounds to document. The result was an outsider’s impression of the town and its spirits; a semi- fictional, wordless, audio-visual poem featuring an Australian performance artist as a spectral transgender deity.

Around this time, I revisited Chris Marker’s poetic reflection on memory, the experimental essay film Sans Soleil (1983) and explored the work of Japanese photographer Lieko Shiga. Both artists, in very different ways, combine documentary, found footage and dreamlike fictional elements to create transcendent art. Shiga’s surreal series, Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), shot over four years in the lead up to and aftermath of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami, is a creative collaboration with elderly local residents, many of whom lost their homes, possessions and photographs. They are often depicted in a luminous chromatic nightscape, seemingly captured by flash in moments of inexplicable activity. These staged scenarios, alongside the artist’s land art interventions, reference the devastation caused by the tsunami and local nature mythology. Projections from the collective unconscious, the images appear just out of reach of rational interpretation yet suggest the inextricable relationship between humans and nature.

Lieko Shiga, Rasen Kaigan 39, 2009, from the series Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2008–12, chromogenic print

Wilkes, John, untitled, 1979.

Time has softened the shadow of my father’s early passing, but his influence is indelible. A polymathic artisan and autodidact, he introduced me to arthouse cinema, the counterculture, philosophy, underground art, blues music and absurdist humour. He taught me to appreciate weirdness, to find beauty in details and old things, to take solace in nature and the vastness of the cosmos. He was wise, idiosyncratic, anti-authoritarian and highly conscious, to his detriment. My troubled collaborator and confidante.

John Wilkes, untitled, 1979, oil painting

The monochromatic blue painting, untitled, was created in my father’s final year studying fine art, while he was exploring themes of cybernetics, modern technology and science fiction. He dropped out of college three weeks shy of graduating, after overhearing his teachers discussing their

cynicism about the art world and the prospects of their students. Nonetheless, he painted and created constantly throughout

his life. All material held potential for some kind of invention, experiment or transmutation.

Trauma begets trauma. Memory merges the past with the present, for better or worse – a magic spell and curse. Burdened by existential suffering, sensitives and empaths often become translators of the numinous. Those who persevere long enough to share the light and wonder of their imagination give meaning to the mystery and madness of being human.

Adele Wilkes is an artist and filmmaker whose practice encompasses moving image, sound, photography, projection and installation, with a focus on expanded, experimental, poetic and hybrid modes of documentary and cinematic storytelling. She is particularly interested in the transformative potential of collaborative, experiential, sensory and ritual processes.