The Koorie Heritage Trust’s Affirmation exhibition brings together four multi-disciplinary Aboriginal artists - Paola Balla, Deane Gilson, Tashara Roberts and Pierra Sparks - whose photography practices author land kinship and interrogate the illegitimate truths of the federation.1 The exhibition initially came about as a contribution to the Photo2020 International Festival of Photography, which has been postponed until next year. And yet Affirmation, which I had the pleasure of visiting IRL between Naarm-based lockdowns and which can be viewed digitally here, is important and remarkable enough in its own right that it needs no festival scaffolding.

Holding over 48,000 original and duplicate copies of historical photographic items, the thirty year old Aboriginal owned and managed non-for-profit Koorie Heritage Trust has established a unique relationship with the photographic image. The role of archival photography and its legacy within Aboriginal communities is crucial to understanding and decoding the myths such images have helped inform. The interrogation of constructed myths and false histories is a recognisable artistic practice which Cheryl Simon states is ‘a late stage manifestation of postmodernism appropriation.’2 Operating as a commercial outlet, education and exhibition space, the Trust provides a compelling nexus to understand the constructed falsities of the Aboriginal image ... As a trusted institution, how does the Trust’s archival collection actually impact the nature of the works it exhibits?

The camera as a tool to engage with the past and with Indigenous memory is integral to the Affirmation exhibition. Whether or not it is present in the same space as the exhibition, the Trust’s photographic archive exists as a cerebral appendage of Aboriginal memory. Fifteen years ago, Marcia Langton argued that ‘[t]he problem with analysis of the visual representation of Aborigines lies in the positioning of us as object, and the person behind the camera as subject’.3 Satirical engagements with historical falsehoods, such as in Deane Gilson’s ceramic collage, dictate an undeniable authority by inserting bodies of power where they had previously been withheld. In an act of subversion, Deane’s recontextualisation of Captain Cook's bronzed image uses the technologies of objectification that were historically used to capture the Aboriginal image. Corporeal absence in photographic practices also allows mob to interact with images in an inexplicit manner. Anthropomorphic qualities in both Pierra and Tashara’s work illustrate an Indigenous perspective in opposition to the body as a commodity, whereby the power of focality is given to the land. The possibilities of emotional contention are invited by the way Pierra and Tashara work to inhabit Country as an appendage of memory. Much in the same vein can Paola Balla’s Mok Mok series be understood. As an engagement with the body as a tool to inhabit Indigenous stories and experiences formerly hidden from view, her work challenges the myth of absence of Aboriginal justice systems. As Mok Mok stares directly into the eyes of her viewer, control over the image’s intent is unwavering, without passivity.

The piercing eyes of Paola Balla’s reimagining of her matriarchal ancestral figure Mok Mok, from her Wemba Wemba Country, deliver a staunch welcome — upon entering Affirmation this is the first image you see. A treasured figure passed down by her mother and her mothers’ mother, ‘Mok Mok used to thrill me as well as frighten me because I thought: “What a powerful woman,”’4 Balla writes in ‘Walking in Deadly Blak Women’s footprints’. Artistic practice that seeks to address the systemic silencing of First Nations voices solidifies Mok Mok as a symbol of justice; as Balla asks in the exhibition text, ‘who could punish the perpetrator?’

We live in a nation that imprisons more Aboriginal children than any other in the world at the same time that ‘reconciliation’ is put forward as a solution to ongoing colonial violence. The heavy shadow of so-called justice is a burden delivered by the settler state to Aboriginal communities. Emotional outcries from the community easily become a commodity for the Australian media to use however they please. Without an acceptable visual code to justify emotional outcry, the image of injustice perpetrated against Aboriginal people seems inexplicable to the Australian media. Mok Mok’s reckoning with the lens seizes narrative control and scope from viewer to subject. Surrounded by multiple generations of women, Mok Mok represents justice as whole and encompassing, not separate from culture and relative to her modern surroundings. Emboldening cathartic energies, Mok Mok’s unapologetic glare insists justice is not separate from emotion and is not discounted because of it. The viewer is involved in the uncomfortableness of injustice in this cathartic encounter. Nestled amongst Australiana and Aboriginal kitsch, all already a part of Paolo’s house, situates Mok Mok within a frame of reference. Baking, cleaning and hanging out the washing ... no matter the context, Mok Mok remains adorned in native flowers and Dilly bag, reiterating that culture and justice need not sit in opposition. Balla talks back to that which relegates Aboriginal justice to a relic of the past, a myth furthered by the culture of photographing First Nations people.5 The agency to create and explore Mok Mok in a space of sanctity with kin in the backyard becomes more important than the implication of a witness, or viewer. ‘Mok Mok was a way to heal myself and try and find (the) fearlessness I needed,’ remarks Balla in the exhibition text.

The historical relationship between photography and First Nations people has been characterised by racist government ethnography, tourism and government programs of protection and assimilation. Nicholas Peterson argues that images circulating at the beginning of the twentieth century of Aboriginal people and their families fit into two prevalent moral discourses. Firstly, as visual evidence to explain impoverished circumstances, and secondly as evidence of the need for institutional intervention. Visuals that justify government intervention have long lasting legacies. Indeed, these ‘legacy images’6 have only recently become accessible to the community, and non-Aboriginal owned institutions and museums still maintain masses of these images. Colonial archives have remained largely inaccessible to mob, and there remains contention around the protocol of using images. Depictions of our people at the hands of injustice, legitimised and curated by a lens, can to some degree account for First Nations’ desire to reconfigure the body, spirit and narrative historically portrayed by photography. The international practice of working with archival legacies, or what Cheryl Simon calls the ‘archival turn’ of the 1990s, attempts to address the buried histories of war and genocide. It is by no means a coincidence that the increased use of archival photographs and artefacts in artistic practices correlates with First Nations’ methods of decoloniality. The re-making of visual meaning with archival images can also be likened to photographic practices that disregard the body as a point of interest entirely. Both attempt to decode the body as a site for colonial power, talking back to the colonial image that helps justify government violence.

In an Instagram exchange with Pibbulman Noongar artist Pierra van Sparkes, I asked if she considered the colonial depiction of country and mob in photography, and if the absence of a body in her photographic series was related.

I think it’s really interesting how you have interpreted these photographs as speaking to archival photography objectifying mob. This isn’t something that I intended to directly speak to — but definitely something that I was thinking about when putting the works together, and generally with my practice. Thinking about Paola’s work considering artistic Terra Nullius, what does it mean when body/ies are absent in these works depicting Country?

Does this meaning change at all when the subjects of the photos are specific details of Country, as opposed to depicting an expansive ‘empty’ landscape? … With the works, a part of processing feelings of liminality living and growing up off Country, I think this absence reflects feelings of loneliness or longing that can be part of this experience. Having said this, these feelings are accompanied by that of love all at once. Country grows and changes — as does ‘home’ — but it feels constant at the same time.

... As for the works feeling romantically entangled (with) Country — they certainly were intended to depict intimate moments between myself and Taungurung and Noongar Country, with each photograph working to practice being present and shift my gaze from the horizon to the beautiful details of Country before me.

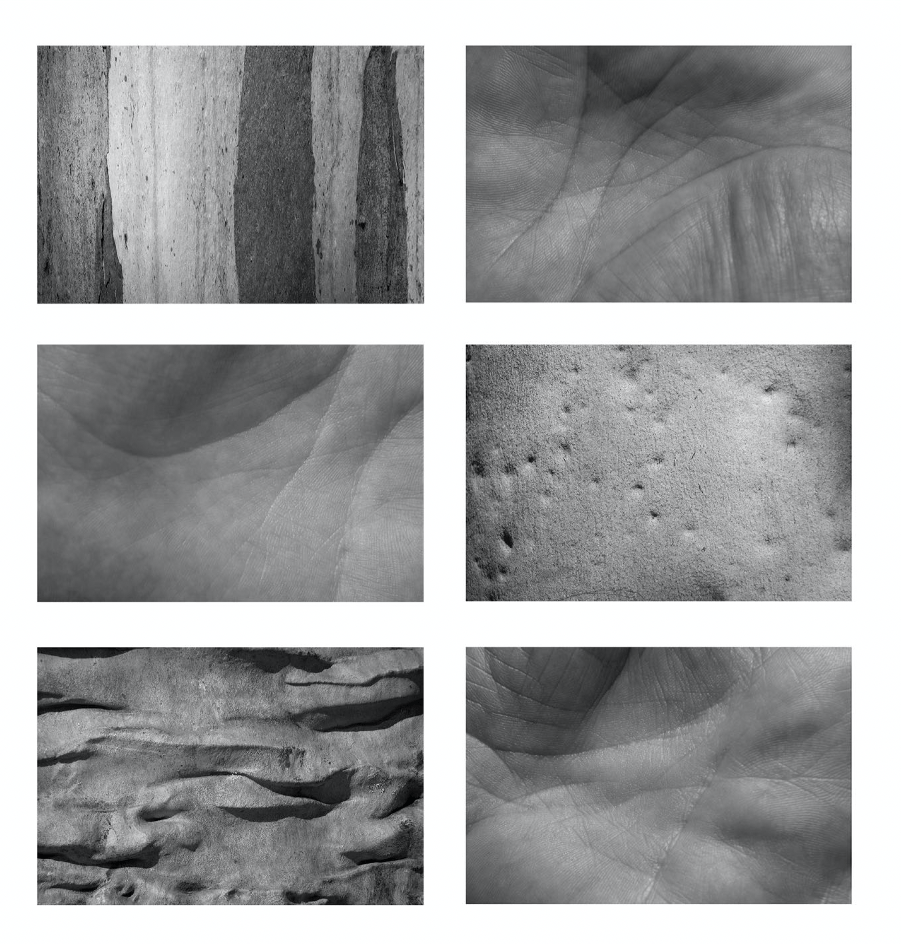

Dja Dja Wurrung and Yorta Yorta artist Tashara Robert’s photographs of Indigenous trees growing throughout Victoria portray an intimate relationship with her Country. Images of tree skin positioned alongside Robert’s palm offer a compelling and almost indistinguishable visual. The absence of a body in these images invokes connections between material and immaterial that expresses a longing to connect with Country. Evoking a need to reach out and touch Country, to feel it on your skin; gapila, a Dja Dja Wurrung word that means ‘to know through touch’. The privileging of Country over body within the context of photography denotes an importance not witnessed within colonial/ legacy imagery, which lends dominance to man over nature. In the same vein as Pierra’s work, the close affinity to Country delegitimises colonial narratives. These images give breath to an Aboriginality not subservient to a white gaze, but instead depicting identity through a relationaly to country. ‘Their skin is our skin, their blood our blood, their pain is our pain, and their loss,’ remarks Tashara. These black and white images bring to mind what might have been photographed by the subjects of those historical archives if given the opportunity ... what they might have found important to commemorate.

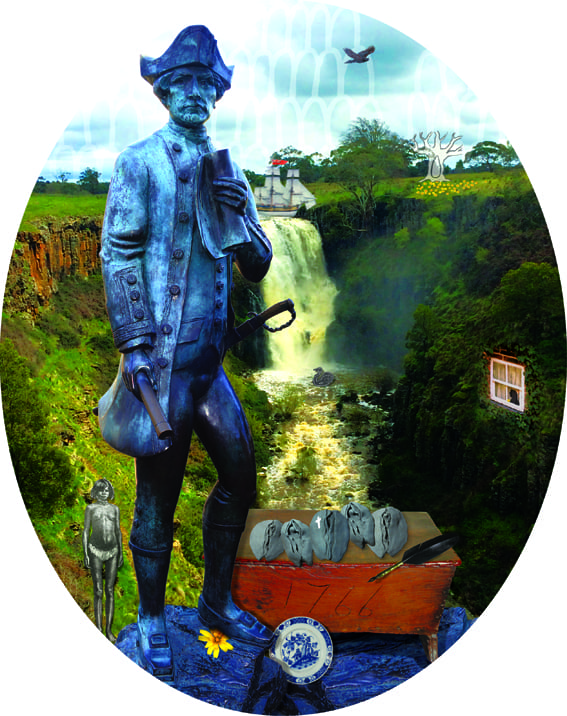

While the other artists in the exhibition symbolically reference archival histories or absence thereof, Deanne Gilson’s digital collage shields actually use archival imagery, including Queen Mary of Coranderrk and Captain Cook. In the eyes of many Australians Captain Cook remains a hero; every year the nation is torn between celebrations and Aboriginal mourning of James Cook’s so-called discovery of Australia, a ‘discovery’ that erases the 65,000+ years of continued occupation of this nation by its first people.7 Gilson's high gloss ceramic shields reconfigure colonial narratives that position Captain Cook as a hero figure in Australian history. In Gilson’s rendering, the archetypal hero seems irrelevant standing in front of the visually dominant waterfall, the memory of Country and its legacy incomparable to the blip in history that is Captain Cook. This is in stark contrast to the way Queen Mary of Coranderrk is depicted, standing adorned in yellow Murnong flowers, her belonging to the space undermining the legitimacy of Cook’s portrayal in history. The smaller shields symbolise the way Country and its people were commodified. With the Golden Stars of Murnong reoccurring all over the shields, Deanne signals hidden narratives and invites viewers to investigate further. A subtle visual testimony to the sophisticated farming methods of pre-colonial food cultivation, the flowers of the murrnong were grown and harvested for their swollen starchy roots; today the English name for these is ‘yam daisy’. Their inclusion in the photomontage falsifies the myth that there weren't farming practices before colonisation.

Just another theft, alongside the theft of history, writes Claire G. Coleman. Gilson’s works justify the repurposing of colonial imagery to debunk the myths of so-called Australia, myths substantiated by archival photography. The First Nations body also becomes a site of mythology in the colonial archival image, the result of a Eurocentric approach to photography coupled with the consumerist view of the body as a commodity. Whether a deliberate approach or the way the photographs have been distributed, this particular perpetuation of colonial mythology silences Aboriginal histories, such as farming technologies and systems of justice. It is not that photographic evidence of these histories doesn't exist, rather they weren't and still aren't circulated with the same vigour as photography that favours corporeal form. Gilson’s subversive use of the Murnong flower in colonial archival imagery speaks to this absence and challenges a narrative of colonial supremacy, as does the work of all the artists in this exhibition.

Jenna Rain Warwick is a proud Luritja woman, emerging artist and publishing writer whose work speaks to her desire to champion the creative imagination of First Nations peoples. Jenna is the 2020 un Writer in Residence.