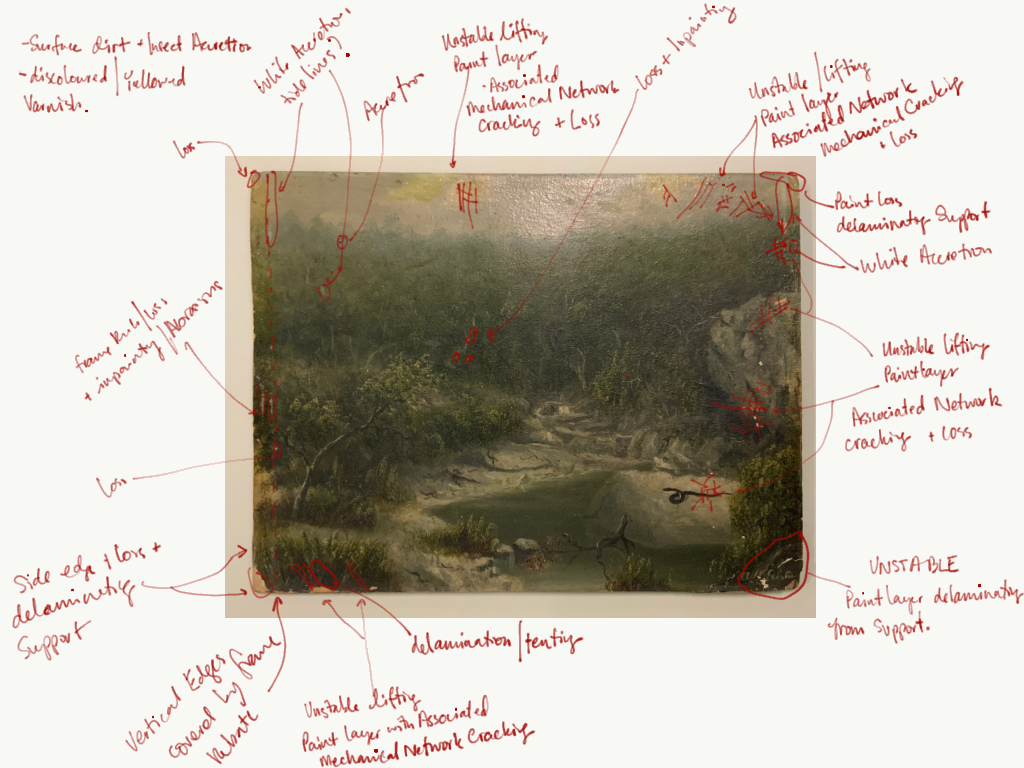

Image: Annotated Image of A.W. Eustace, Untitled (snake on a rock), c.1870-1880 oil on cardboard, 235 x 308mm: Image courtesy of the Murray Art Museum Albury and Emily Mulvihill.

Walking around the gallery space with an art conservator’s eyesight, I see paintings in a very specific way.

I always start with colour.

I see warmth or coolness. The vibrations or the movements. The dust, dirt and grime settled atop the canvas’ surface. I see the artists’ choices in the brushstrokes – what is original and intentional and how the selection of materials illustrates concepts and meaning for the maker. But I also see the materials that are out of place and the decisions and actions made overtime; the damage, deterioration and inherent change all a part of a painting’s journey through time and space. This superpower of sight has been developed through my education and practice as a conservator, allowing me to conduct condition assessment and conservation treatments on paintings.

When I think about the annotated bibliography my mind is instantly diverted to the annotated image, which is the way art conservators extend the annotation practice from text to artwork. The annotated image is a common tool used in conservation and comprises a surrogate image of an artwork that has been ‘marked up’ noting the location/s and describing the characteristics of the paint surface, damage or change, artist hand and other anomalies. As an example, (figure) I have completed an annotated image of A W Eustace’s Untitled (snake on rock), c.1870-1880 oil on cardboard, 235 x 308mm, which has been recently donated to the Murray Art Museum Albury by the artist’s family. Within the painting’s central image there are annotations locating sites of lifting, cracking paint, paint loss, in-painting, surface dirt, accretions etc. This image fixes the condition of the painting to a point in time and becomes an essential documentation related to

the original artwork that allows professionals to assess the condition before it is accepted into the collection and enables future conservation treatment. As well as recording the condition of the artwork, it also acts as a tool to familiarize the conservator with the painting. Through the actions of building the annotated image, you get to know the painting, understand it, see it differently.

When thinking about the skills I’ve developed and the skills I use to create an annotated image, there are two important texts that have helped me. Firstly, Charles Velson Horie’s (2010) Materials for Conservation, organic consolidants, adhesives and coatings is a reference book of polymers used in conservation and art practice. Polymers are chemical compounds made up of small molecules that repeat and create a larger molecular structure and are generally synthetic organic materials used in resins and plastic. The second book is by Michael O’Toole (1994), The language of displayed art, which presents a framework to understand the semiosis (meaning making) of the artwork. It takes the discursive practices of text and text analysis and applies them to another mode of meaning, that of art. Both books balance the different knowledge sets needed when examining a painting: the material and the conceptual, in other words, the form and meaning- making function.

Horie, Charles Velson. 2010 Materials for Conservation;

organic consolidants, adhesives and coatings. 2nd ed.

Routledge, New York, NY.

Charles Velson Horie has made enormous contributions to

the field of conservation through his publication record. His contributions to museum environments, paper conservation, archaeological conservation, natural history conservation, audio-visual material conservation, polymers in conservation, management and professionalism in the conservation industry extending from the early 1980’s until today are unparalleled.

In addition, he has held committee roles in international conservation bodies such as the International Institute for Conservation (IIC). Horie’s (2010) book is an extensive reference guide on the material characteristics of polymers used in conservation and is on every conservator’s bookshelf. Horie (2010) feels to me like a reassuring mentor there on the shelf ready to support me when I have exhausted my response to the obvious materials needing a conservation treatment and I need refreshing on the more obscure ones, or I need refreshing on the solubility parameters of a polymer which we use every day.

Horie (2010) helps support conservators from the moment we start to examine an artwork or object. For example, Horie (2010) has shaped the way I see and examine the work, A.W. Eustace, Untitled (snake on rock) c.1870-1880. The text supports me as I decipher what the materials are telling me. One of the first things I notice is the painting’s surface quality. It appears hazy, even murky. It is like the edges of the brushstrokes are blurred. The surface has an even and dull sheen that could be described as a yellow taint. There are also an array of brushstrokes: thin, short, wide, long and small, with fine valleys in the individual brushstrokes from where the hairs of the paintbrush have been pulled through the wet paint. Numerous shades of different paint, from warm and cool greens, to greys, browns and yellows, through to variations of whites, which suggest where the sun hits the trees. With all this variation in the paint layer, I would have expected there to be the same variation in the surface sheen. This discrepancy of evenness on the surface’s sheen, the varied paint types and application suggests that a surface coating has been applied. Horie (2010) can help identify this surface coating and guide the conservator to the possible next steps in a conservation treatment. Horie introduces the conservator to one aspect of conservation, namely, ‘The properties of organic consolidants, adhesives and coatings as they affect the treatment of objects.’ Untitled (snake on rock) was painted in c.1890 and this helps indicate what type of coating may have been used. With the advancement of polymer science and the development of different synthetic resins, we know that there was a limited amount of commonly used resins available around the turn of the century. The yellowing of the surface coating, as well as the date of the painting suggest that the surface coating is most likely a natural resin, either Dammar or Mastic. As noted in Horie (2010), Dammar replaced Mastic as a common picture varnish in the early 19th century and one can assume that the coating on Untitled (snake on a rock) is a Dammar resin. However, one can only be certain after scientific analysis. Horie (2010) is a text which helps build my knowledge of materials used in art objects and conservation.

O’Toole, Michael. 1994, The Language of Displayed Art, Leicester University Press, London UK.

Michael O’Toole’s The Language of Displayed Art is a more obscure text for conservators and was introduced to me by my linguist mum, Dr Elizabeth Thomson. This early, seminal work in the semiotics of art practice takes the principles of patterned practice from the tradition of systemic functional grammar developed by the linguist, Professor Michael Halliday. Halliday describes language as a semiotic system of meaning-making and linguistics as the study of ‘how people exchange meanings by ‘languaging’.’1 From Halliday’s perspective, ‘language has the property of not only transmitting the social order but also maintaining and potentially modifying it’.2 Given this understanding, the theory is also appliable to other semiotic systems of human creativity, including visual arts.

Here, O’Toole (1994) applies semiotic theory to understanding the meaning-making potential of visual artworks. As O’Toole (1994) acknowledges in the first pages of his book, ‘My thanks are due above all to M A K, Halliday, whose systemic-functional theory of language inspired and informed at every point the semiotic model which I have applied to the visual arts’. The framework consists of three meta-functions of a system of meaning-making potential: modal/interpersonal, representational and compositional.

The modal/interpersonal function of an artwork is the relationship of the audience to the artwork. This encompasses how it engages the viewer’s attention, thoughts and emotions, and how the audience relates to the picture, and to the techniques and materials that the artist has used. The representational function is what is physically being depicted, what the viewer may ‘read’ from an artwork, related to what they ‘know’ about the world. Lastly, the compositional function knits the other two meta-functions together as the three work simultaneously in the process of semiosis.

In my experience, the act of conservation typically works on material changes within the artwork which were unintended by the artist and can impact on the modal meta- function in the sense that these changes have the potential to change the artist’s intent. Equally, the act of conservation should not interrupt or change the representational and compositional functions of a painting. In other words, it should not interfere with the intended meanings of the artwork. For example, when examining A.W. Eustace, Untitled (snake on rock), associated paint loss, cracking and delimitation of the paint layer are labelled on the annotated image. This damage or these changes and loss of the paint layer alter the representational function with any loss of paint never intended by the artist. The literal loss of paint from the painting means the loss of meaning. Therefore, it is unwanted and can be labelled as such and then addressed in a subsequent conservation treatment, which will restore the representational function of the artwork. In understanding these different functions, I have found assurance when assessing a painting.

The framework helps categorise what I am seeing on the surface and links it to the meaning or function of the artwork. It also helps identify unwanted change, deterioration or damage in the materials of the painting. These changes can be paused, removed or altered to bring the artwork back to its original intent through a conservation treatment. The semiotic framework presented

in O’Toole (1994) has helped me initially draw meaning from an artwork and later, as my career in conservation progressed, gave me confidence in my conservation practice to identify areas within an artwork as unwanted change.

These two texts, Horie (2010) and O’Toole (1994), have influenced my professional work but they have also annotated my life. Walking around with a painting conservator’s eyesight does not just start and stop when I look at artworks, especially paintings. I have a vivid memory from when I lived in New York City and was working for a modern and contemporary painting conservation studio. I remember the lifting and delaminating paint layer on the walls of the West 4th Subway station in Manhattan, which I would stare at on my way home from work. It looks like a thick, evenly applied, dark grey paint layer that I estimate to be an acrylic. With the influence of Horie (2010) burning a hole in my brain, I can guess which polymers would work the best to adhere the paint layer into a planar position, taking into consideration the extreme fluctuating environment (being exposed to the hot humid NYC summers and its bitter, dry, cold winters). But then, O’Toole (1994) reminds me to consider whether or not the paint layer serves in the construction of semiosis. In this case, it does not. And that’s because the subway station is not a work of art and the paint layer’s function is purely practical. I call off my superpower as, in this instance, I do not need to intervene – instead deciding to board the train and go home.

[^1:] Halliday, 1985. “Systemic Background”. In Systemic Perspectives on Discourse, Vol. 1: Selected Theoretical Papers from the Ninth International Systemic Workshop, Benson and Greaves (eds). Vol. 3 in The Collected Works, p. 193.

[^2:] Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. “An interpretation of the functional relationship between language and social structure”, from Uta Quastoff (ed.), Sprachstruktur – Sozialstruktur: Zure Linguistichen Theorienbildung, 3–42. Vol. 10 of The Collected Works, 2007.