Stanton Cornish-Ward & Trent Crawford, In A World Full Of Angels, 2022, HD Video Still. Image courtesy the artists and Gertrude Contemporary.

The following texts and filmic references were instrumental in the creation of In a World Full of Angels (2022), a short film commissioned by Gertrude Contemporary that is currently available to view online as part of their Digital Commissions program. Channelled by the film’s main character, a pilgrim skydiver, these texts and filmic references have been transubstantiated into the film to construct a mosaic vision of faith amidst turbulent technological and historical developments.

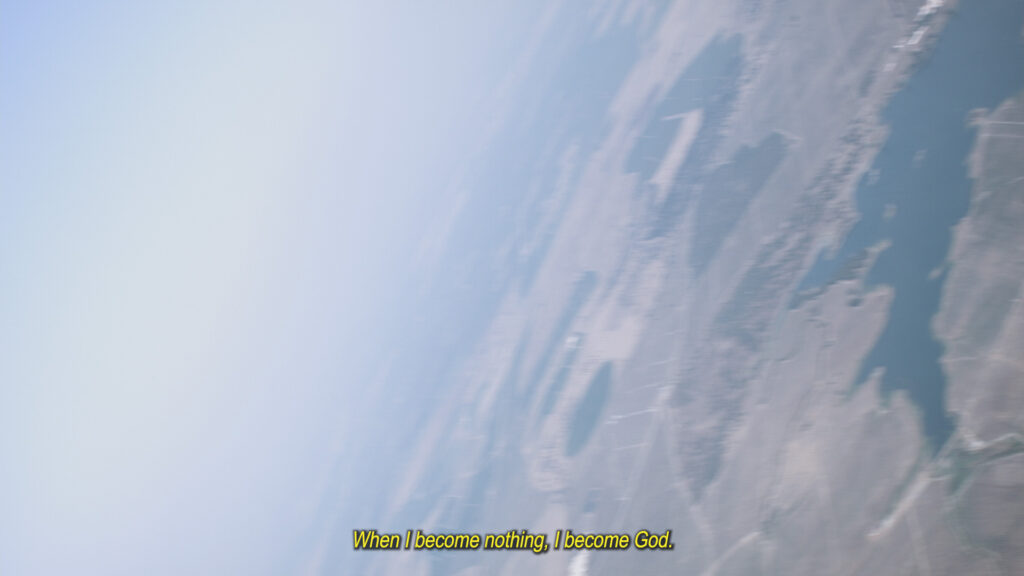

If these references share one inherent quality, it is an eschatological concern; surrounding the end of the present age, human history, and the world as we know it. For us, the figure of the skydiver presents a pertinent position from which to think through such concerns—emblematic of a perspective at the tail end of rapid technological growth and garnered with an angelic ability to encounter experiences that defy our long history as merely earth-bound creatures.

Our aim here is to offer an extended guide to the film (a decoder of sorts), as well as a more focused critical extension of the film’s central artistic question—to what degree does history as much as theory become instrumentalized when grappling with existence in a seemingly groundless and destabilised world?

We are grateful to Hilary and D for giving us this opportunity to unpack these references and allow them to sit in open relation beyond the bounds of the film.

Porete, Marguerite. The Mirror Of Simple Souls.

Translated by Ellen L. Babinsky. Paulist Press, 1993

Having refused to disavow her book, The Mirror Of Simple Souls, Béguine Christian mystic Marguerite Porete, was condemned for heresy and burnt at the stake in 1310. For centuries her work circulated in secret anonymously, until 1946 when Italian scholar Romana Guarnieri identified Porete to a Latin manuscript of The Mirror in the Vatican. Following the revival of her work, Porete and the Béguine movement have been identified as a vital precursor to modern feminism.1 Her work emphasised a detachment from the material world. A perspective embraced by many Béguines—groups of pious women who lived in self-sufficient women-only communities in Mediaeval Europe.

In a beautiful and poetic exploration, The Mirror outlines the seven stages of annihilation the Soul must pass through on its path to oneness with God. The text offers captivating conversations between ‘Love’, ‘Reason’ and the ‘Soul’. These personified elements discuss in a lively fashion the trials and tribulations of the Soul’s journey, with ‘Love’ and ‘Reason’ constantly debating the best way forward. A radical text for the 14th century, it is clear to see why the movement Porete inspired was seen as a threat to the clergy. For once the soul has passed through the seven steps of annihilation, there is nothing to separate the soul from merging with God itself. What Philosopher Simon Critchley labelled a process of ‘self-deification’.2

The Mirror was an influential reference point when building the Skydiver’s motivations and personal philosophy. Unable to resolve the world around them, both Porete and the Skydiver seek spiritual resolution in the face of a conflicting internal dualism; a choice between retaining their sense of self and the annihilation of that self in alignment with greater forces. In the Skydiver’s pursuit, she contends with an internal death drive reminiscent of Porete’s own forceful tones: ‘One must crush oneself, hacking and hewing away at oneself to widen the place in which Love will want to be’.3 Repeatedly diving towards the ground, and always one intervention away from her own mortal destruction, she seeks deeper meaning behind the coming calamities. When on Earth, she is confronted by a series of fractured events. In freefall, in the clouds, everything seems to fall in place.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Benjamin, Walter. Theses on the Philosophy of History.

Edited by Hannah Arendt, Translated by Harry Zohn.

Illuminations, 1968

A well-trodden site of inspiration for generations of thinkers, Benjamin’s written animation of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) has long been a point of fascination for those grappling with time and feelings of groundless contemporaneity. Captured in Theses IX of Theses on the Philosophy of History, Benjamin dons Klee’s figure, the Angel of History, and describes an angelic figure whose face is turned towards the past, whilst violently being propelled backwards into the future by the unrelenting storm of progress. The storm catches the angel’s wings with such violence, that he can no longer close them; helplessly pushed by a force predicated upon destructive ruination whose debris grows ever higher in front of the angel’s feet.

Initially, we had planned for In A World Full Of Angels to open with an adapted transcript of Theses IX. The text played a central role in the initial development of the film, having helped us form the notion of a divine witness; a figure whose experience of history is guided by divination and unity between historical events. We formulated the skydiver angel as an embodiment of this position. A manifestation of catastrophic consciousness, caught in her attempt to resolve a similar paradigm to the angel of history; alignment between oneself and the forces of progress, divine power and history.

As a whole, Theses on the Philosophy of History calls eerily and passionately for the weaponization of history. For certain historical moments to be strategically ‘blasted out of the continuum of history’ and harnessed for their revolutionary potential.4 Benjamin attempts to draw a clear line between certain uses of history, namely by opposing the intentions and actions of the historicist with those of the historical materialist. Today, such distinctions appear even less clear. This tension falls at the heart of the film, which aims to complicate these frameworks through the consideration of contemporary forms of minor historicism; both neo-religious and conspiratorial. Thus, the film’s active framing of historical moments is not to be left unscrutinised. The formulation of these woven narratives is in part an open question to Benjamin, aimed at thinking through the inherent subjectivity in attempting to define and dissect such righteous formations of history.

Theses on the Philosophy of History was the last major work of Benjamin’s career, written shortly before his attempted exodus from France and subsequent suicide. The text is noted for its distinctly theological flavour, which has caused much discussion as to whether these messianic impulses are merely a poetic means of writing about historical materialism or indicative of Benjamin’s own spiritual turn later in life.5

Duras, Marguerite (Writer) and Resnais, Alain (Director).

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959).

Criterion Collection, digital remaster 2013. DVD

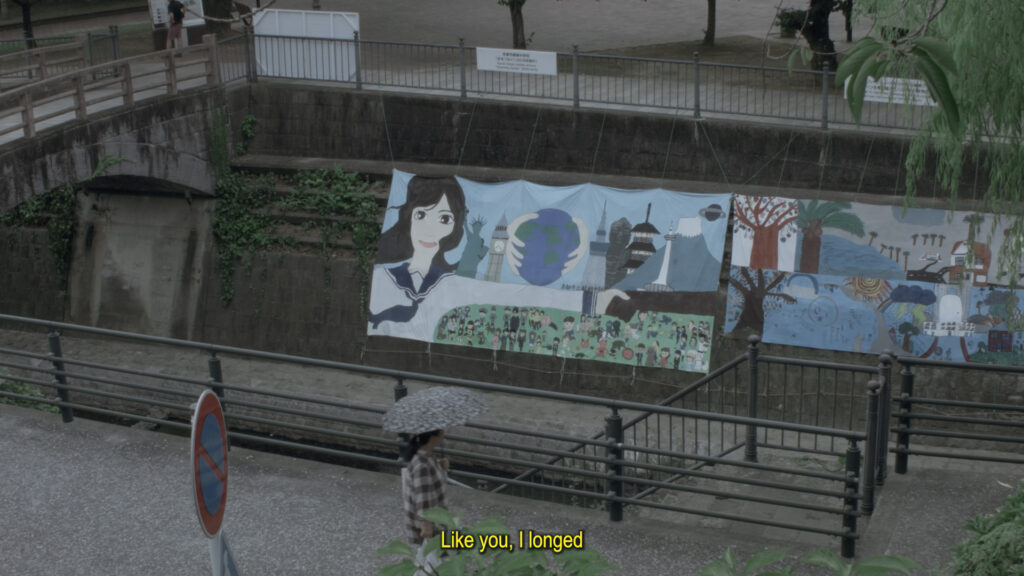

Set in rebuilt Hiroshima fifteen years after the city was devastated by the atomic bomb, Hiroshima Mon Amour is a story of a romantic encounter between a French actress (Elle) and a Japanese Architect (Lui), and their series of long fleeting conversations reckoning with their own inescapable histories over a 24-hour period. A palpable sense of anxiety encircles the pair as they grapple with each other’s perspectives in relation to their own place in history. What French director Eric Rohmer identified aptly as ‘anguish of the future’ predicated upon ‘a film that plunges at the same time into the past, the present and the future.’6

‘Take me. Deform me, make me ugly’, Elle whispers to her lover, Lui in the infamous 15-minute opening scene. Elle’s urge to be obliterated by her lover in order to deal with her own overwhelming contemporaneous existence coincidently echoes the words of Marguerite Porete. Both Elle and Porete talk about the annihilation of the self through forces greater than themselves—following a similar dominant motif—the desire to be subjugated into a new form, outside the current reality in which they stand. If we could disappear into this new incarnation, the pain of the past would be alleviated (if only for a fleeting moment, between lovers).

Time and memory exist simultaneously and interdependently within the film. Duras and Resnais shatter any sense of time with past and present scenes woven together in coexistence, rather than as isolated, semiential flashbacks. Through carefully crafted events, the film portrays how the circumstances of the past can have a lasting impact on the present. ‘I saw everything in Hiroshima’ whispers Elle to Lui. ‘You saw nothing in Hiroshima’, Lui whispers back, as dust showers down on their embraced, naked figures, an evocative reminder of bodies in the rubble of war, covered in atomic dust.

A key element to the film is the viewpoint of the outsider—an emotional struggle to grapple with something that one has not experienced themselves and the inherent distance such divisions in experience can create. The Peace Museum in the film acts as a vehicle to which one can imagine, or at least try, to place oneself in the tragedy of others through pure visuality. But this of course, Lui points out, is flawed. To ‘see’ is not to know, to know is to ‘experience’. Lui’s integration of Elle’s feelings about Hiroshima, and Elle’s integration of Lui’s feelings about wartime France, are the closest both get to experiencing the personal tragedies of each other. Tragedy is opened up past the framing of flash burnt relics, melted glass, building rubble, aerial photographs and scorched clothing, and permeates into the very souls of those it has touched.

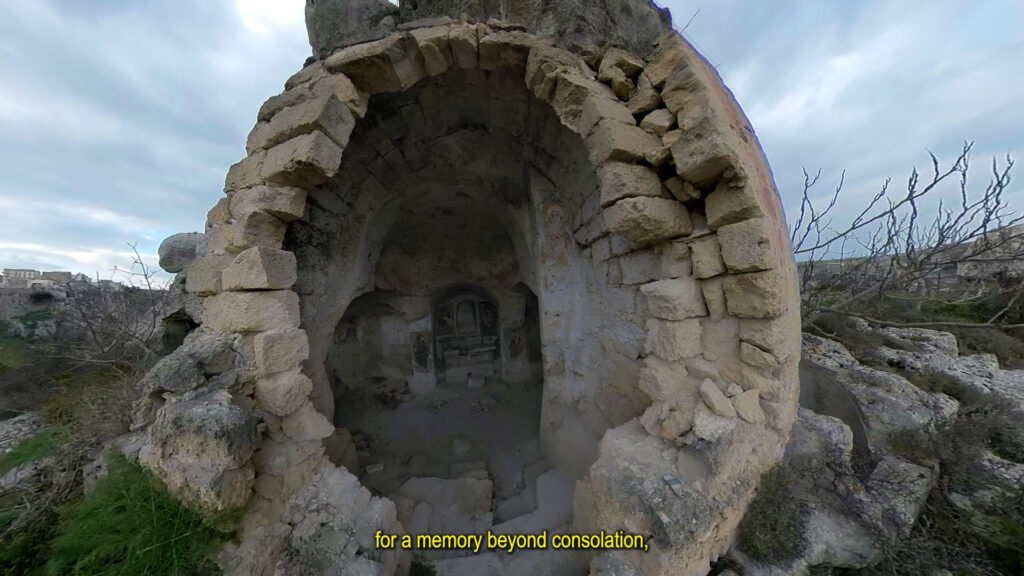

Stanton Cornish-Ward & Trent Crawford, In A World Full Of Angels, (Madonna degli Angeli Matera, Italy) 2022, HD Video Still. Image courtesy the artists and Gertrude Contemporary.

Hayashi, Kyoko. Trinity to Trinity. Translated by Otake, Eiko. Station Hill Press Inc, 2010

Having known people in the World Trade Center who died

in the 9/11 terror attacks, performance artist Eiko Otake came

to Koyoko Hayashi’s work as a way to grapple with her own contemporaneity in relation to the event and her fear of military retaliation. By reading and translating Hayashi’s work, which confronts an alternative terror—the legacy of the atomic bomb— Eiko felt she would be able to get a clearer perspective of historical moments through the lens of personal tragedy.

When she was 14, Hayashi nearly died on August 9th, 1945, during the atomic bombing of Nagasaki while she was working at a factory close to the epicentre. Hayashi’s work, Trinity to Trinity, moves back and forth through moments in her life—the present and past always in dialogue with each other— unravelling the ripples of tragic events. The main thread of the book follows her visit to the Trinity Test site in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico, the location of the first ever atomic bomb test. Here she sees her own origin and kinship with the desert, as the birthplace of all Hibakusha (the Japanese term designated for atomic bomb survivors).7

In the introduction to the text, Otake unveils another foundational element of Hayashi’s work—presented in Safe (Buji, 1981).8 The idea that a new era of human history began the day the first atomic bomb was detonated. Hayashi argues that any prior religious event pales in comparison to the atomic bombings and their global implications. Therefore, she concludes that the year 1945 should be year one on the renamed ‘A-bomb calendar’ to mark the start of the new era. While reading this text we imagined the skydiver coming across this idea in her own research and building it into her own beliefs around ‘divine intervention’—a term all too commonly associated with nuclear catastrophes.9

Later in Trinity, Hayashi addresses a poem by Yasuko Ito to a person named ‘Rui’, detailing the destruction and loss of bodies by the Urakami Cathedral, which at the time stood 500m away from the epicentre in Nagasaki. The Cathedral at the time of the bombing was the largest in Asia. In the poem, Ito references Saint Francis Xavier and Apostles, key figures in bringing Christianity to Japan through Portuguese trade routes. In the same breath she warns of an impending nuclear winter coming to cover all of the Earth: ‘History passed Hiroshima and Nagasaki / And came this far / standing on the ruins of the Cathedral in Urakami’.10 After the poem, Hayashi signs the letter with:

— The world does not need your experiment.

— Rui, What do you think?11

In the afterword, Otake identifies ‘Rui’ as not a real person Hayashi is addressing. An uncommon name in Japanese, ‘Rui’ is a homonym for the Japanese word ‘species’, referring to the compound ‘human-species’. Hayashi is addressing this letter to us.

Steyerl, Hito. In Free Fall:

A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective.

E-flux April Issue #24, 2011

Quick-witted and prophetic, Hito Steyerl’s In Free Fall captures an acute shift in perspective at the dawn of the twenty-first century. The increased presence of the ‘God’s eye-view’ via Google Maps, 3D fly-throughs, drones, satellites, and aerial surveillance footage has diminished the role of the horizon as a consistent point of reference, causing a paradigm shift in our spatial and temporal understanding of the world and, in turn, our place in it.

For Steyerl, this shift in horizon is evocative of a discordant dualism between the perception of extreme stability and total instability. Stability, represented in the form of a drone: fixed, stabilised, and operated from a distance, the drone’s topographic vantage point does away with the horizon entirely in its embrace of remote objectivity. Instability, situates in the figure of the skydiver who, in groundless free fall, witnesses fractured and multiplied horizons, reflective of the present inability to perceive ‘stable ground on which to base metaphysical claims or foundational political myths’.12

Steyerl’s line of inquiry echoes that of Walter Benjamin in his infamous text, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935). Facing a saturation of new technology, advancing cinema and photographic reproduction, Benjamin argues that these mediums had a profound change on the status of a work of art and of the image of the proletariat. While many disdained the perceived devaluation of the singular, original image, through reproduction, Benjamin saw this shift to hold revolutionary potential, as ‘mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual.’ Thus allowing images to better serve political ends.13

Drawing a similar line, Steyerl concludes her essay on a hopeful note, remarking, ‘Perhaps these new representational freedoms help question whether we really need a ground in the first place.’14 This contentious question falls at the heart of Angels. As Benjamin’s emancipatory potential falls into doubt, following a landslide of democratised image production. A decade after the publication of In Free Fall, we feel it is necessary to consider the degree to which ideological formations proliferate today not in spite of groundlessness but precisely in the embrace of it.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo (Director).

La Rabbia di Pasolini, 1963.

Istituto Luce, DVD, 2008

In these shouts of boundless assemblies,

in these lights,

in these mechanisms,

in these declarations,

in these armies,

in these weapons,

in these deserts,

in these unrecognisable suns,

the new pre-history begins.15

La Rabbia di Pasolini is a scathing critique of early 1960s Italian politics and culture and a wider critique of western hegemony

at large. A notable forebearer to the modern video essay, the film’s poetic narration, voiced by Pasolini himself, plays over footage from various events, including those in the Congo in the 1960s, atomic blasts of the 1950s, the Hungarian Revolution, the Algerian revolution, the Cuban revolution, a celebrity visit by Sophia Loren to an eel festival, and exploitation of workers at a Fiat plant. The text is structured from the perspective of many different characters musing over the contemporary world. Through these point-of-view vignettes, Pasolini’s ills with the modern world are laid bare—constructing his own retelling of the twentieth century. A form of active lyrical historicism that interweaves archival material through a sprawling set of relations.

The film was originally commissioned as one half of a forced compilation, called La Rabbia (the Rage), which paired the work of two opposing Italian intellectuals: the radical left-wing filmmaker, artist and poet, Pasolini, against the right-wing journalist and satirist, Giovannino Guareschi. Unaware of each other’s involvement, both were asked to respond to the same question: ‘Why is our life dominated by discontent, anguish, by fear of war, and war itself?’ Both were to utilise the same archive footage to craft their response. Ignorant of this set-up during production, Pasolini was disgusted by the false premise and immediately denounced the film upon its release. The film performed poorly and was withdrawn from circulation, until 2008, when it was reconstructed into a version which omitted Guareschi’s section and was retitled La Rabbia di Pasolini for the Venice Film Festival.

Pasolini actively dismisses chronology, instead relying on his own political beliefs and poetic sentiments to form the governing narrative to structure the film. We were drawn to this style of creation, not as an assertion of our own political or spiritual beliefs but as a method of implicating the footage itself as an active reflection of the film’s protagonist. La Rabbia di Pasolini inspired the formation of In a World Full of Angels as a subtle POV film, whose imagery may appear to have been recorded and reconstructed by the pilgrim skydiver as a record of her journey. Like Pasolini, the skydiver freely wields and interlinks these recordings of foreign historical sites and events to form a theological argument that comes to terms with her own existence in a divided and chaotic world.

La Rabbia di Pasolini concludes with a glimpse of the future, beyond the Earth’s horizon. It muses on the soviet side of the space race occurring during this period. Pasolini voices a young cosmonaut, a symbol of prophetic unity. Having returned from the heavens, the cosmonaut leaves the viewer with a lesson from above: ‘I come down to Earth among my comrades of hearts, simple and great, for great is my nation. And I bring with me the consciousness of a new sun, until now lost in the future and conquered today, old hope of an unforeseen love.’

Jackson, Mick (Director).

Threads (1984).

BBC, 2013, DVD

The hands of the Doomsday Clock—a symbol of how close humanity is to a man-made global catastrophe (created by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board

in 1947)—had just reached their closest point to midnight (3 minutes)16 at the time of the release of Threads in 1984. Today, the clock sits 100 seconds until midnight, a new record.17

For the first time the threat of a Nuclear winter for younger generations is no longer abstract but a potential reality; brought back into the public consciousness with the escalation of Russia’s war against Ukraine—through selective targeting of nuclear sites, first with the Exclusion Zone and Power Plant in Chernobyl and later the Zaporizhzhia Power Plant. We are witnessing something we had never seen before in nuclear discourse—the emergence of ‘nuclear energy terrorism’.18 We revisited Mick Jackson’s Threads during the start of the war, the first British production to capture the extended fallout of nuclear winter in a neorealist style.

The film was introduced to us by artist and Maumaus lecturer Simon Thompson as a horrific artefact forced upon his generation in high school. If the Cold War generations lived through what could be described as ever-present nuclear anxiety, what Millennials and Generation Z have lived through to this point is ambient nuclear anxiety.

We were only cognisant of the threat through shared cultural references, far from the duck and cover drills that our parents experienced. Set in Sheffield, England during the height of the renewed Cold War in the 1980s, the film depicts the effects of a nuclear war and fallout on the city and its inhabitants told through the eyes of two families, the Kemps and the Walkers. Jackson, at one point considered casting actor from Coronation Street, but opted to use unknown actors to heighten the film’s impact. The budget was also modest, choosing instead to withhold certain moments off camera for audiences to fill-in-the-blanks as to what horrors are unfolding. Jackson spent months travelling around the UK and the US to meet with eminent scientists, psychologists, medical professionals, defence experts, and strategists to provide the most accurate portrayal of a nuclear winter, and the results show. Threads is as striking now as it was during the renewed Cold War, a staple form of civic propaganda that scarred children and adults alike.

Threads takes out all of the glamour and slickness of apocalypse that we have grown accustomed to in twenty-first century media. What is portrayed is a visceral and urgent look at what could be our collective near future. The film’s unrelenting bleakness coupled with its vivid foresight of nuclear fallout shows us not just the trauma, but the collapse and erasure of our way of life in the aftermath. This aspect is perhaps what unsettled us the most—not just how traumatic the initial shockwave would be but the immediate and long-term disintegration of collective meaning.

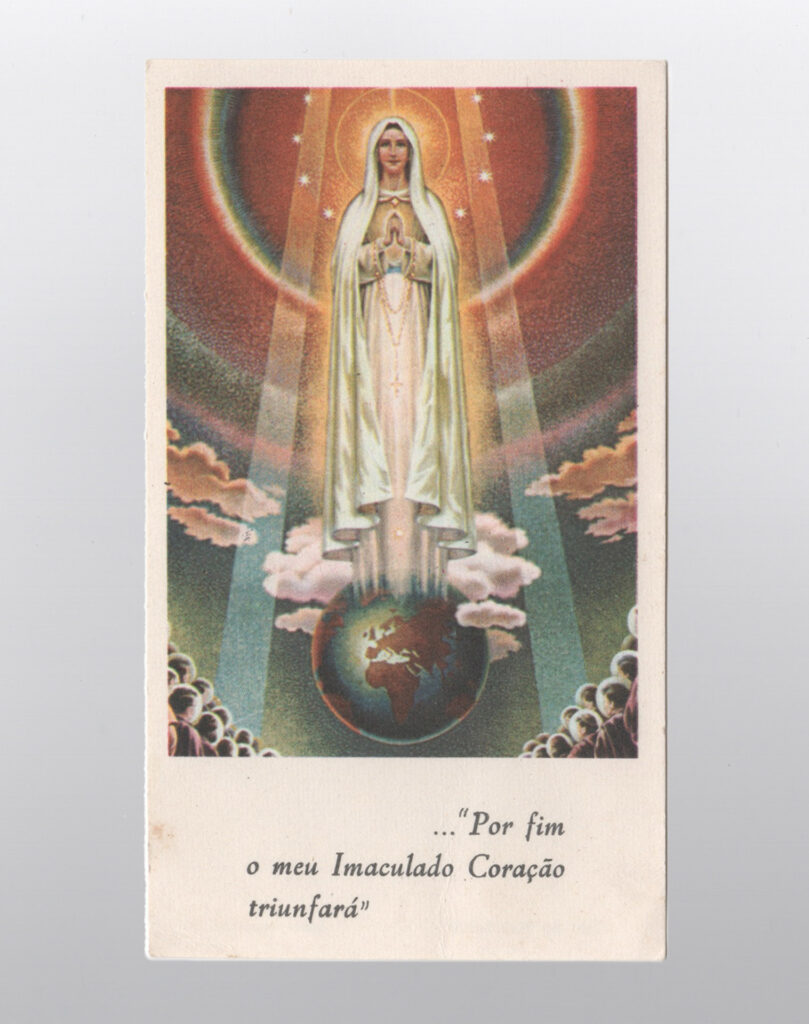

Act of Consecration to the Immaculate

Heart of Mary Prayer. Libreria Editrice Vaticana,

online. 25 March 2022

Star of the Sea, do not let us be shipwrecked in the tempest of war.

Ark of the New Covenant, inspire projects and paths of reconciliation.

Queen of Heaven, restore God’s peace to the world.

Eliminate hatred and the thirst for revenge, and teach us forgiveness.

Free us from war, protect our world from the menace of nuclear weapons.

Queen of the Rosary, make us realise our need to pray and to love.

Queen of the Human Family, show people the path of fraternity.

Queen of Peace, obtain peace for our world

...You once trod the streets of our world;

lead us now on the paths of peace19

Our Lady of Fatima is a series of Marian apparitions that occurred once a month for seven months in 1917 in Fatima, Portugal. A vision of Mary appeared to three young shepherd children, Lúcia Santos and her cousins, Francisco and Jacinta Marto. She showed the children three apocalyptic visions and prophecies: first a vision of Hell. Second, the end of WWI, with a new war to begin should mankind continue to offend God (including if Russia was not consecrated into the Immaculate Heart of Mary). And a third vision, which remained sealed by the Vatican until 2000, and is still disputed to this day as to its validity. The apparitions came to a head at a final event called ‘The Miracle Of The Sun’, where over 70,000 people at the site in Fatima witnessed the sun cast multicoloured light and dip down towards the Earth, causing mass panic, before zigzagging back into the heavens. It is considered one of the most important and well-documented Marian apparitions of the twentieth century. Our Lady of Fatima is often invoked by Catholics as a powerful intercessor, especially for peace.

The second vision has been interpreted to be the foretelling of WWII, which foreshadows the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima—decoded in the vision as the ‘night illumined by an unknown light’.20 We visited both Hiroshima and Nagasaki back in 2019, which was a sobering experience on the horrors of Nuclear warfare. With the escalation of the war in Ukraine, it brought back almost forgotten nuclear fears into the public zeitgeist. This fear of forgetting was an important throughline to the film given that the framework of mutually assured destruction has never wavered since the Cold War.

As a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Pope Francis on March 25th, 2022, consecrated Russia and Ukraine to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. The prayer for this ceremony was rewritten to reflect the present tense and was last updated in 1984 at the height of Cold War tensions. The above is a section of the prayer that deals with themes of war and nuclear weapons. We attended the consecration service in Fatima while similar services were being conducted across the world, at locations including the Vatican and the site of a less well-known Ukrainian Marian apparition, Dzhublyk. The same prayer was translated into 36 languages for these services. On the day, many in attendance held Ukrainian flags, as we all bowed and recited the prayer together as a crowd. Many tears were shed; it was an opportunity to express the misery of revisiting a barely healed wound.

Trent Crawford is an artist and filmmaker based in Naarm Melbourne whose work considers the impact images and image-based technology have on notions of truth, belief, and agency. In recent years he has exhibited artworks at 4649, Tokyo (2022); Palazzo San Giuseppe, Italy (2022); ACE, Tarntanya Adelaide (2021); Hobiennale, nipaluna Hobart (2019); Myojuji Sarue, Tokyo (2019); and Auto Studio, Beijing (2018). He was awarded the Keith and Elisabeth Murdoch Traveling Fellowship in 2017 and the Anne & Gordon Samstag International Visual Arts Scholarship in 2022 which he used to participate in the Maumaus Independent Study Program in Lisbon, Portugal.

Stanton Cornish-Ward is an artist and filmmaker based in Naarm Melbourne of Ukrainian and Bungandidj heritage. Her work looks at the fallacy of memory, intergenerational trauma, and the effects of emerging technologies on the human condition. She is one half of Hiball, a film production company specializing in moving image for the digital world. Her film work has been part of the official selections of film festivals in Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Ireland, Germany, Hong Kong, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Romania, Spain, Mexico, U.K, and U.S.A.

Jean Domarchi, Jacques Doniol- Valcroze, Jean-Luc Godard, Pierre Kast, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer: ‘Hiroshima, notre amour’ (discussion on Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour) (July 1959). In Cahiers du cinéma (p. 67). essay, Harvard University Press.

org: Japanese Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from jisho.org/word/%E8%A2%AB%E7% 88%86%E8%80%85

midnight - Bulletin of the atomic scientists. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from thebulletin.org/sites/default/ files/1984%20Clock%20Statement.pdf