My annotated bibliography contains carefully selected texts

and images that, over time, have become crucial to my practice as a writer and researcher. As someone who identifies as an Australian Muslim, many of the works that have resonated with me are those that discuss issues and topics that are close to my heart and my own personal experiences: Islamophobia and Orientalism; the experience of growing up Muslim in a settler- colonial state after the events of 9/11; Islam as both a cultural and a religious entity; and the politics of ‘Whiteness’ within the context of Australian society. My practice is a hybrid between the creative and the theoretical. I use my own short-story and novel writing to explore the research questions that I have for myself whilst practicing within the field of Australian Muslim writing; a criminally under-researched and underappreciated facet of Australian writing. All the works I have included in this annotated bibliography have either inspired or aided my journey of inquiry. I seek to appraise how a creative writing practice can rework culturally ingrained, racist narratives about the Australian Muslim community, which have long fed Australia’s Islamophobia problem, by creating new narratives that reflect the community’s varied experiences and relationships with their identity. The ways in which we cultivate knowledge are integral to how we view ourselves and our place in the world. The right to articulate our experiences is frequently denied to marginalised groups and minorities, especially the Muslim community who face the consequences of a centuries old Western scholarly tradition known as Orientalism. Edward W. Said has identified Orientalism as a ‘... Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient’ (p. 3, Said) and it has since transformed to what we now refer to as systemic Islamophobia. I believe it is my ethical obligation as a creative practitioner to ensure my practice consults a wide range of published information alongside a myriad of personal experiences—my own included—to represent community within my own creative work. I consider it to be my life’s mission to advocate for my own community and work to facilitate cultivating our own knowledge, so we are represented in a way that acknowledges our humanity and the diversity of our lived experiences.

Orientalism,

Edward W. Said (2003)

Edward W. Said’s Orientalism is a key text when it comes to any discussion involving Orientalism and Islamophobia. It is an essential reference to lay the foundations for any argument reflecting the systematic cultural racism Australian Muslims have endured. These texts aid in understanding from both a historical and an ontological perspective. Every power- knowledge structures—such as educational institutions or the pervading forces of the media—that have led to everyday Western society. In Orientalism, Said provides a comprehensive definition of what Orientalism is as well as the parameters of its application, whilst examining the binary logic that has justified many European imperialist and colonial projects across the globe. He also delves deep into the origins and history behind the Western scholarly tradition of homogenising non- European cultures into a singular cultural identity which has been termed the Orient. For Said, the Orient makes for an easy way for the West to conceptualise the East as ‘... then in need of corrective study by the West’ (p. 41, Said). Much of the Western scholarship on the Orient highlights its supposed ‘backwardness’ and inferiority in all aspects to European culture, allowing the Occident (the non-Orient countries of the ‘West’) to situate itself as the dominating and superior culture.

At the height of the European Enlightenment period, the Muslim world saw itself become enveloped under a cultural homogenisation where Western scholars compartmentalised the cultural and religious diversity of Muslim nations into only one notion to consider: the ‘non-European’. This allowed Europe to assume a position of cultural superiority over Muslim and Arab societies as the ‘us, the Europeans’ versus ‘them, the non-Europeans’. It became the fore fronting logic in much of the discourse surrounding the compatibility of non-European cultures with European culture, i.e. Islam as a non-European religion is inherently incompatible with European culture based on it being non-European (p. 7, Said). This led to the systemic ‘Othering’ of the Muslim identity within Western societies as their supposed non-European status suggests an inability to assimilate into Western culture. While Said does navigate through a long history of Orientalism, one that examines its roots in Islamophobia from the time of the Crusades, he also emphasises that Orientalism is not just a phenomenon of the past, which makes his work as relevant as ever. In the 2003 Penguin edition, Said includes a preface where he addresses the rise in Islamophobia after the events of 9/11, an event that perpetuated beliefs that the Muslim world consisted of uncivilised countries that, due to unstable governance, were ruled by religious fanaticism and violence. He notes in the early 2000s that this ‘simplified’ view of Arabs and Muslims was allowed to inform disastrous US Foreign policies and the ‘experts’ on ‘Middle Eastern’ politics who advocated for military intervention in Iraq and a US imperial expansion. Said also identifies the dehumanising language used by US congress to announce these military campaigns in Iraq with particular mention of one congresswoman’s description of it as ‘take[ing] out Saddam [and] destroy[ing] his army’, the lives of the Iraqi people completely disregarded (p. xxi, Said). The support for the Iraq invasion by the US-led coalition (including Britain, France and Australia) saw the lives of the Iraqi people translated to the ‘enemy’, pathing the way to justify war crimes and humanitarian violations (pp. xxi-xxii, Said). The war coverage of the Iraq invasion spawned a media craze for showcasing Muslims as terrorists and religious fanatics, which was used to ‘validate’ the atrocities of the Iraq invasion, a phenomenon that Said refers to as ‘neo-orientalism’. Newspapers and current affairs programs led the way for the West to attain their information on Islam. For my own work, Said’s concept of ‘neo-orientalism’ is useful in my understanding of how power-knowledge structures continue the marginalisation and ‘Othering’ experienced by the Australian Muslim community post-9/11 and the subsequent invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. The preface to this 2003 Penguin edition helps ground Said’s theory in reality, giving insight into how institutions further cultural superiority in Western nations.

Tales from the Arabian Nights,

translated by Sir Richard Francis Burton (2012)

Tales from the Arabian Nights (or One Thousand and One Nights) is an anthology of classic Arabic folktales compiled by English translator and literary scholar Sir Richard Francis Burton. While the anthology itself comprises compelling work borrowed (alongside its title) from classical Arabic literature, my interest in this text lies with Burton’s efforts in translating and publishing it for a European audience. As a Victorian literary scholar in the height of the Orientalist obsession, Burton spent much of his career pouring over classical Arabic manuscripts as he delighted in the ‘exoticness’ of the stories that he predicted would shock and offend Victorian Britain’s sensibilities. In 1888, Burton finally published his own English translation of the Arabian Nights and garnered outrage amongst his contemporaries. The Edinburgh Review claimed that Burton’s anthology was ‘... an appalling collection of degrading customs and statistics of vice’ (p. 326, Kennedy). Burton’s intention to scandalise Victorian Britain can be found in forewords included in various editions of his compilation where he expresses his desire to challenge the Victorian ideals of moral puritanism through these stories (p. 320, Kennedy). The history behind Burton’s publication of Tales from the Arabian Nights is an intriguing study of how the Orientalist scholar can translate and transform traditional Arabic stories into what Burton perceived to be ‘scandalous’ erotic literature due to its ‘non-European’ cultural origin and thus its inherent opposition to Christian values and morality. It problematises the way the Orientalist gaze influences the English translations of non-European manuscripts and consequently how these non-European literary traditions are represented in the West.

Islam, Arabs and the Intelligent World of the Jinn,

Amira El-Zein (2019)

Islam, Arabs and the Intelligent World of the Jinn is an exciting contribution by poet and scholar Amira El-Zein towards the field of Islamic cosmology; a study that uses the Qur’an and the hadith (sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhmmad (SAW)) to make sense of both the ‘seen’ and the ‘unseen’ world. El- Zein applies traditional Islamic methodologies, which include the Qur’an and the hadith as primary sources, to produce comprehensive research on the topic of Jinns and their relative essentialism to an Islamic world view. According to both the Qur’an and the hadith, Jinns are intelligent beings made up from smokeless fire and considered to be part of the ‘unseen’ world. To justify her research focus on Jinns, El-Zein begins by referring to the importance of intellectualising Islam, as both a culture and religion, beyond the usual dialogue that the ‘West’ (that is, Europe, America, Australia etc.) gravitates towards: Islamic fundamentalism, the status of women in Islam, the veil, and the complex conflation of ‘Jihad’ with terrorism (pp. ix-x, El-Zein). She presents the urgent need for more scholarly work on the topics more attuned to the heart of Islam, all the while transcending the limited view the West has of the Muslim world: that it is a society that values dogmatic jurisdiction above all else. In order for there to be a full appreciation for Islam, the West must learn how Muslims see the world through a completely different cosmological framework. A pool of enlightenment intellectuals has strived to understand the world through strict teleological binaries such as ‘logos’ (material reality) versus ‘mythos’ (myth) to uphold narrow definitions of what constitutes ‘reality’. By contrast, Muslim intellectuals interact with a world that comprises the ‘seen’ and ‘unseen’; where science mediates with religion, the difference between the two not easily discernible (p. xvii, El Zein). For El-Zein, Jinns play a pivotal role in showcasing how both the physical and metaphysical world are the Muslim’s reality, for belief in Jinns is considered mandatory in Islam. Throughout the first few chapters, El-Zein maintains that following a Western understanding of the world leads to Jinns being labelled as unscientific and irrational. It is a complex task for Muslims to separate the ‘seen’ and ‘unseen’ world into clearcut binaries of what is material reality and what is mythology. Science and religion go hand in hand for Muslims, thus producing an antithetical understanding of the world: a view that is just as valid as any other. El-Zein’s research on the importance of Jinns provides an alternative venture when engaging with Islamic culture. This line of enquiry works to encourage Muslim scholars and writers who want to draw from existing literature to generate different insights into the Muslim experience.

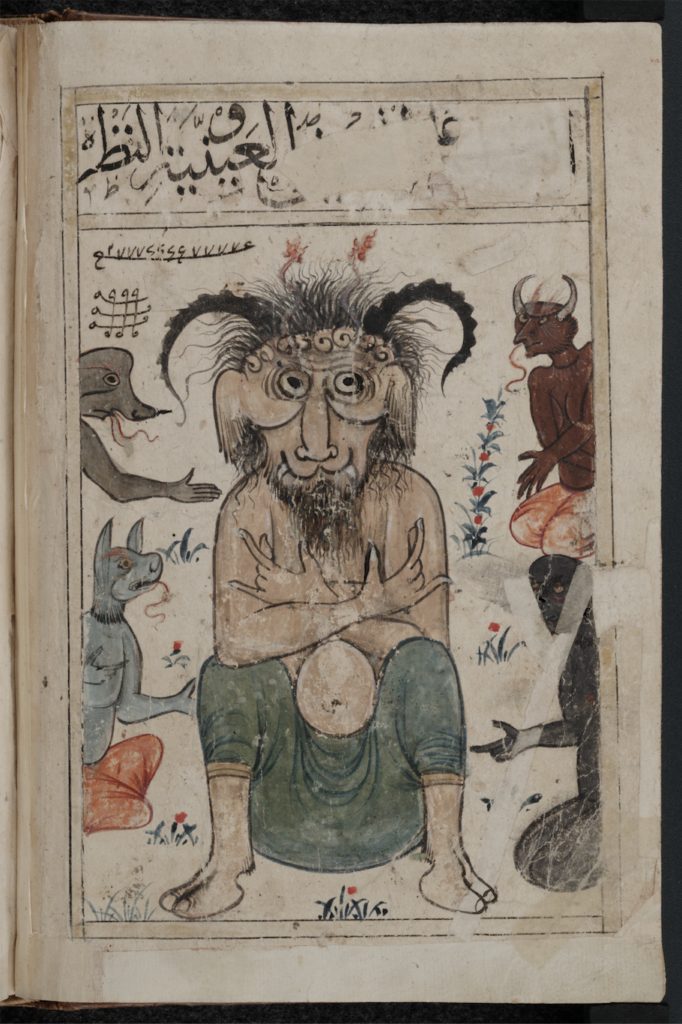

Image of Jinns from

Kitāb al-Bulhān (The Book of Wonders),

compiled by Abd al-Hasan Al-Isfahani

(14th-15th century)

Kitāb al-Bulhān or The Book of Wonders is a 14th–15th century manuscript compiled by Abd al-Hasan Al-Isfahani during the reign of Jalayirid Sultan Ahmad in the city of Baghdad. The manuscript refers to a broad range of topics: from astronomy, astrology and geomancy, to taboo topics such as black magic. It also includes texts and images about Jinns and Islamic prophets from throughout history. Although a relic from the 14th and 15th century, black magic and astrology are haram (forbidden) by the religion and do not reflect practices that are normative to Orthodox or Sunnī Islam, like that of religious iconography. The book is a remnant of a Muslim society that was culturally complex and diverse in its practice of Islam. The image I have selected here is of a group of Jinns, easily identified by their hybrid form of human and beast. Intelligent beings from the ‘unseen’ world that have long enthralled Islamic society, Jinns’ existence serves as proof of their Divine and their metaphysical existence. The Jinn reminds us that Muslim society is not purely driven by the enforcement of religious dogma but is inspired and curious about the cosmos.

Is racism an environmental threat?,

Ghassan Hage (2017)

Is racism an environmental threat? is a polemical text by Lebanese-Australian anthropologist Ghassan Hage, who discusses the politicisation of Muslim identity and how said politicisation has been weaponised to further expansionist imperialist projects. According to Hage, the Muslim body is deemed ‘ungovernable’ by the West due to its perceived loyalty to religious fanaticism above all else, especially that of national identity. This presumed inability to assimilate into Western society positions Muslims, in the eyes of the Western government, as a security threat to be neutralised. The Muslim automatically assumes enemy status and takes up the position of the ‘Terrorist Other’, a front of global terrorism that aims to undermine Western civilisation (p. 45, Hage). Hage goes on to unpack the common use of ‘lone wolf’ imagery when referring to Muslim terrorists by politicians and the media, which insinuates a need to ‘domesticate’ the Muslim body because of its inherent savagery (p. 35, Hage).

He reframes Western intervention in the Middle-East to that of ‘domestication,’ where the West invades the Muslim world in hopes to retain control and order over the national boundaries put in place by Western colonisation (p. 65, Hage). The exploitation brought on by said ‘domestication,’ such as plundering colonised land for resources and the use of exploitative labour of the colonised peoples, results in ecological crisis. The comparison of Western imperialism to that of an environmental threat is a difficult yet necessary parallel that is both literal and figurative for Hage. The very real environmental impacts of Western intervention can be seen in the way that the landscapes of countries such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan have permanently been changed due to war and US imperialism. However, the idea that the Muslim body, in the eyes of Western governments, is comparable to a savage animal, such as a wolf, is a troubling notion that I find hard to digest. Yet, Hage makes a compelling argument as he points out that the constant references to the ‘lone wolf terrorist’ who is unable to assimilate, and how Muslim communities are harbouring these ‘lone wolves,’ are not accidental. It ties into the way that Western imperialism desires to control and subjugate ‘The Other’ by envisioning it as something undesirable, in need of ‘correction’; a pack of ‘lone wolves’ to hunt down and eliminate. It also holds global networks of colonisation to task in terms of the environmental damage they cause across the world and the ecological systems of humans, animals and plants that they disrupt and destroy: an issue that I believe is not discussed enough.

Caravanserai:

Journey Among Australian Muslims,

Hanifa Deen (2003)

Caravanserai: Journey Among Australian Muslims is a book

by Australian Muslim writer Hanifa Deen who embarks on a journey across Australia to collect stories from Muslims with a diversity of backgrounds and experiences. Caravanserai covers a wide range of topics: from migration and multiculturalism, to identity and belonging, nationalism, religion, and gender issues, amongst other facets of the human experience. With much respect and care, Deen documents the stories of the Australian Muslims who share their own unique relationship with their Australian identity and their Islamic practice. I am fascinated by the book’s publication history. There are two different editions: one published in 1995 and a revised edition published in 2003 with an additional chapter. In the Author’s Note of the second edition, Deen mentions that she initially sought to write a book about the Muslim experience that would be more than just a discussion about religious identity; she wanted to capture how Islam fit into the lives of the Australians she was invited into and weave them into a series of short stories. During the Gulf War period of the 1990s, Deen witnessed the way in which the Australian media reduced Muslims to one- dimensional images which proposed problems to the Muslims she interviewed at the time.

Throughout the interviews, many Muslims had expressed to her that they somewhat struggled with their identity but, despite this, remained hopeful of remaining connected with their nationality (pp. 7-8, Deen). However, not long after the events of 9/11, Deen felt that it was important to revisit some of the Muslims she had interviewed almost ten years earlier, including these new interviews in an additional chapter. Her instincts proved right as she found that their relationship between themselves and Australia had become further estranged as they dealt with rejection from the Australian public due to their perceived inability to assimilate into Australian culture. Committed to ending the book on a positive note, Deen expresses her desire to see Australian Muslims able to tell different stories; not the ones of marginalisation and vilification that they had become accustomed to telling (p. 391, Deen). This text is of particular importance to me because it highlights the necessity for Australian Muslims to be able to tell their own stories as the media has been allowed too much free reign to dehumanise and misrepresent us. I also find myself inspired to fulfill Deen’s desire to be able to tell a different story about the Australian Muslim experience. While I will always vocalise my criticism of Islamophobia within Australian society, I aspire to share the ways in which Islam enriches my personal life through my creative practice of short story and novel writing.

The Lebs,

Michael Mohammed Ahmad (2018)

The Lebs is a contemporary novel by Australian Muslim writer Michael Mohammed Ahmad. Published in 2018, the book follows a young Lebanese Muslim boy named Bani Adam who has his adolescence interrupted by the events of 9/11. For Bani and his fellow Muslim and Arab schoolmates, the attack on the World Trade Centre only exacerbates the existing hostile attitudes Australians hold towards young, male Arab Muslims. The media coverage of the infamous ‘Sydney Gang Rapes’ from the year before had already labelled Bani and his friends as likely sex offenders in the minds of the heedless public. And now they must deal with being labelled as terrorists too.

Balancing sensitivity with crude honesty, Ahmad explores the impact of racism and Islamophobia on a seventeen-year-old body who has adulthood thrust upon him earlier than his Anglo-Australian counterparts. Bani must come to terms with navigating a world that is suspicious of his ‘Arabness’ and ‘Muslimness’. I find The Lebs particularly interesting as it is not just a story about a struggle with identity and belonging but a story about a protagonist who struggles with the absurdity behind the construct of identity itself. Throughout the book, Bani finds himself often questioning whether he even knows who or what an ‘Australian’ really is. He comes to believe an ‘Australian’ is simply anyone that is not him. But at the same time, Bani cannot recognise himself in the stereotypes of Muslims and Lebanese people in the media he consumes. The Lebs is a novel that questions whether resolving issues of identity and belonging is enough to end

the marginalisation of Muslims in Australia and, while it does not claim to have all the answers, it does raise the question of whether Australia will ever finally acknowledge that it has a serious race problem that is synonymous with its own sense of identity and nationhood.

Bibliography

Tales from the Arabian Nights. 2012, New York Fall River Press.

Ahmad, M.M., The Lebs. 2018, Sydney, Hachette Australia

Al-Isfahani, A.a.-H., Book of Wonders 14th CE, Bodelian Library.

Deen, H., Caravanserai: Journey Among Australian Muslims. 2003, Fremantle Fremantle Arts Centre Press.

Domain, P., Kitab al-Bulhan, K.a.- B.-B.o. Wonders.jpg, Editor. 1390-1450, Wikipedia Commons. p. Fol. 28b from a manuscript known as Kitab al-bulhan or “Book of Wonders” held at the Bodelian Library. Shelfmark: MS. Bodl. Or. 133.

El-Zein, A., Islam, Arabs and the Intelligent world of the Jinn. 2017, New York: Syracuse University Press

Hage, G., Is Racism an Environmental Threat? 2017, Cambridge Polity Press.

Kennedy, D., “Captain Burton’s Oriental Muck Heap”: The Book of the Thousand Nights and the Uses of Orientalism Journal of British Studies, 2000. 39(3): pp. 317-339.

Said, E.W., Orientalism 2003, London Pengiun Group.