Motifs in Matthew Harris’s lurid works include flowers, copulating pigs, and a gravestone inscribed with a gold sad face. Born in 1991 and raised in Wangaratta, Matthew’s artistic output to date has included video, tapestry, sculpture and painting. He works within a gay camp parlance. Artifice, riffs, cuteness, violence and comic eroticism come together in what could be called ‘bad’ painting. But they are ‘bad’ insofar as they go against the conventions of good taste, and delight in a juvenile preoccupation with obscenity, and sometimes horror. This trash aesthetic, which is tinged with what might be described as ‘regional boganism’, pokes fun at current taste and, in particular, at an urban hipster lifestyle.

Matthew’s paintings can be described as both ‘camp’ and ‘humorous’. The works represent campness through the devices of ‘artifice’, ‘exaggeration’, and ‘stylisation.’1 Indeed, camp and humour are both sensibilities: a grand theory cannot be drawn that covers all camp, and all forms of humour. As Susan Sontag stated in her seminal essay Notes on ‘Camp’:

Any sensibility which can be crammed into a mold of a system, or handles with rough tools of proof, is no longer a sensibility at all. It has hardened into an idea…2

As a sensibility, humour cannot be congealed into a tidy definition. This mirrors its most common mode: in conversation where words are tossed about and subsequently dissipate. Humour’s aim and effect is also very context dependent. Theory can explain certain incidences of humour, but will not be applicable to all. Therefore, as Andre Breton stated: ‘there can be no question of explaining humour and making it serve didactic ends. One might just as well explain a moral for living from suicide’.3 This quality of humour was embraced by Dada which sought to ‘introduce symmetries and rhythms instead of principles’, into art making.4 In Matthew’s work, humour and a camp aesthetic form rhythms that joust and poke at its audience, but do not create an overarching theory.

Matthew combines these sensibilities of camp and humour with bad taste: a trash aesthetic of perversity and horror, which is reminiscent of John Water’s films such as Pink Flamingos (1972) and Female Trouble (1974). Water’s films have been placed within a queer camp aesthetic. ‘Queer’ implies a breakdown of gender seen in transgender, hermaphrodite figures, and abject depictions of bodies.5 Crossing over to visual art this is seen in the work of fellow young Australian artists such as Ramesh Mario Nithyendran and Paul Yore. Matthew’s works at this point are predominately solidly gendered, yet ungendered figures creep in. For example Les Demoiselles D’Uranus (2016) riffs off Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) with female bodies replaced by alien forms. While Matthew’s art digs at normative gender, his primary clash is with normative lifestyle taste, through its crass trash tropes.

Matthew’s works could be read as sitting within the loose genre of ‘bad painting’. They are crude in technique. Paint is layered on thick, not intentionally but, rather, to rectify mistakes. Colour is predominantly deployed to fill in outlines leaving no complicated need to blend; and figures, when they appear, have off proportions . A loose definition of ‘bad painting’ can be found in the press release for an exhibition at the New Museum in 1979, of the same subject matter and title, as art that: ‘discarded classical drawing modes in order to present a humorous, often sardonic, intensely personal view of the world.’6 The assortment of artists exhibited were defined by their opposition to the conventional tastes of the period, which were largely described as ‘visually straightforward, simple forms and objects which constitute the avant-garde.’^7 Now that there is no clearly defined avant-garde, I propose to view Matthew’s work (along with previously mentioned artists such as Ramesh and Paul) as going against art conceived as operating within in a wider cultural setting, where art is linked to lifestyle. When considered within the Melbourne art scene the work taunts at genteel gestural abstraction, and other versions of formalist painting that interrogates the ‘materiality of materials’. This type of art, when translated into a lifestyle, is often ascribed to a loose hipster aesthetic: curated closets, The Design Files; clean-living; a proliferation of houseplants; and design blogger furnishings that spark joy. By creating paintings that are ‘bad’, Matthew voices an incongruous attitude towards this lifestyle.

Madé in Heaven (91 × 61 cm) is a portrait of Matthew’s boyfriend that reveres in the personal and the vulgar within a camped domestic environment. The main ‘joke’ is a riff on Jeff Koon’s candid 1989 series Made in Heaven staring his then porn star wife llona Stallar. Like Koon’s pornographic images, Madé is portrayed on his hands and knees from behind, his arsehole forming the centerpoint of the image. His head is turned to look at the viewer, and besides him sits a panting poodle that also stares back. The floor is patterned with love hearts that tilt upwards, breaking with classical perspective, while outside the moon rises amongst branches in classic picture book style. This combination of the explicit and the camped sentimental, the pornographic and the domestic, disrupts normative standards of taste with humour.

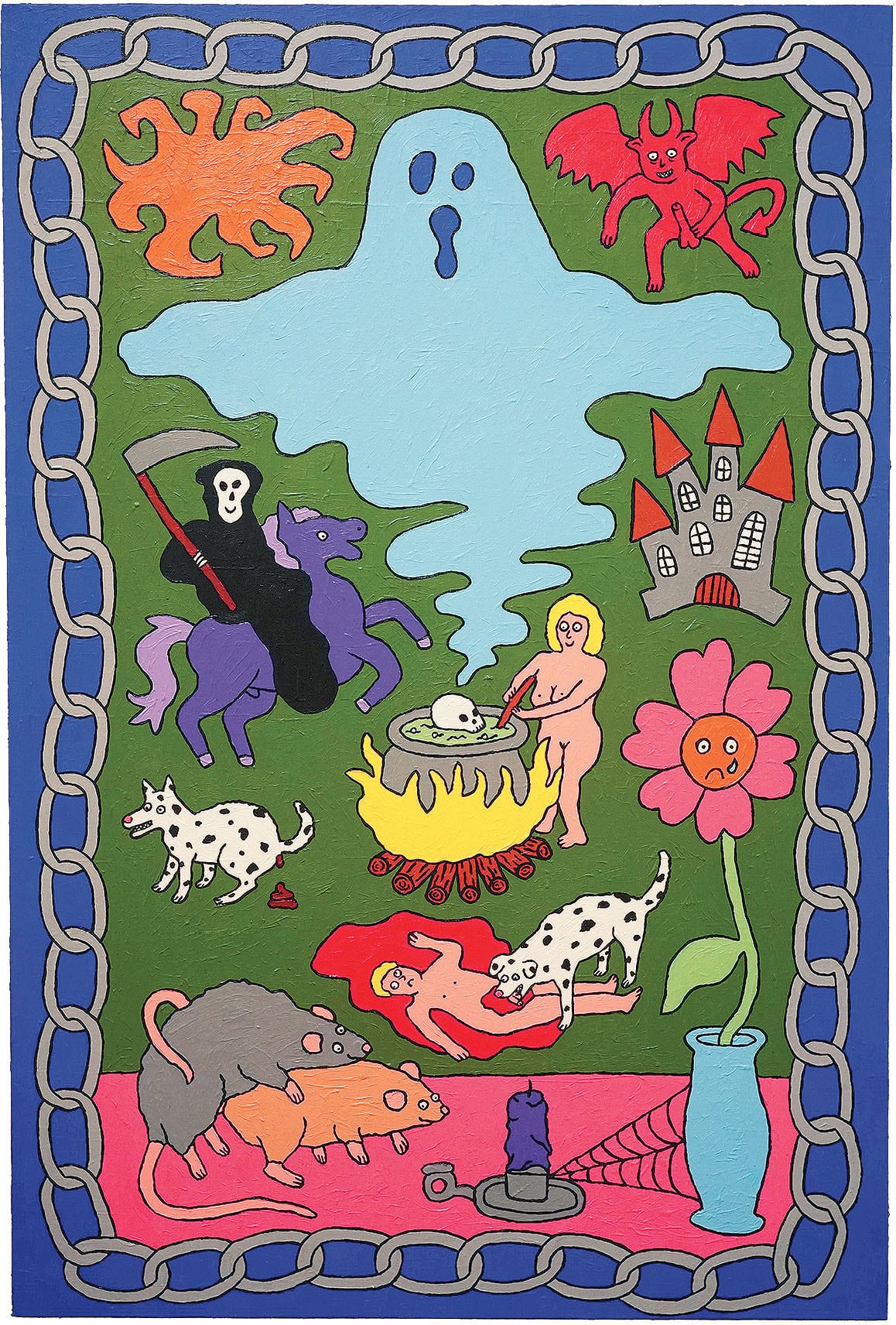

Many of Matthew’s works also operate within a classic Freudian conception of humour, the id (repressed sexual desire and violent forces) rupturing the ego (social conventions of taste, morals and manners), with ‘taste’ being urban hipster and contemporary art norms. This conception is confronted by camped bogan bad taste; motifs of lower-class regionalism that act like the bogeyman to conventions. Take, for example, I Hate People (2017) which contains a riotous assemblage of medievelesque images that draw upon Matthew’s suburban childhood. A man lies in a pool of his own blood while his genitals are eaten by a dog, his face showing annoyance rather then pain; two rats copulate, their carnal act softened by one rat’s tender curling of his tale over his mate; a dog defecates in the corner; the grim reaper rides a purple pony. All this is watched over by a ghost who emerges from a skull in a cauldron stirred by a modern day naked witch, and is bordered by a chain akin to those that boys would use to attach their wallets to their jeans in the 1990s. Here, childhood fascination with cruelty and sex is compressed and ‘camped’ into exaggerated cartoon-like forms creating a ‘quotation’ (as Sontag said, ‘camp sees everything in quotation marks’) that shoves at taste through humour.8

Pig’s Fucking (2016) is another demonstration of Freudian barbarity puncturing through the ego. This painting draws inspiration from Melbourne’s Collingwood Children’s Farm, where inner city children come to see and pet farm animals in an idyllic, romantisiced environment. Here, Matthew recalls watching two pigs corner, trap and eat a pigeon: an event that he recorded on his cell phone. In the painting, these two pigs now have googly eyes and copulate on a puddle of mud, a lewd amorous motif that is repeated across a green backdrop, forming a wallpaperesque pattern. The id that privileges sex and violence is conflated within the emblem of the pig, which simmers on the ego of the canvas (with wallpaper acting as a domestic fragment of civilisation). Meanwhile, the sculpture Sad (2015) moves the subject matter from the home to the graveyards of suburbia, taking the ‘dark joke’ to the extent of absurdity and near collapse. Here, Matthew uses the strategy of placing two unalike things together, an emoji-like gold sad face is imprinted on a tombstone. The sad face mocks death’s gravity. Yet, while some jokes use dark humour to elevate mortality, this work leaves the viewer sitting within the condition, not sure whether to laugh it off or pass it off as a bad joke.

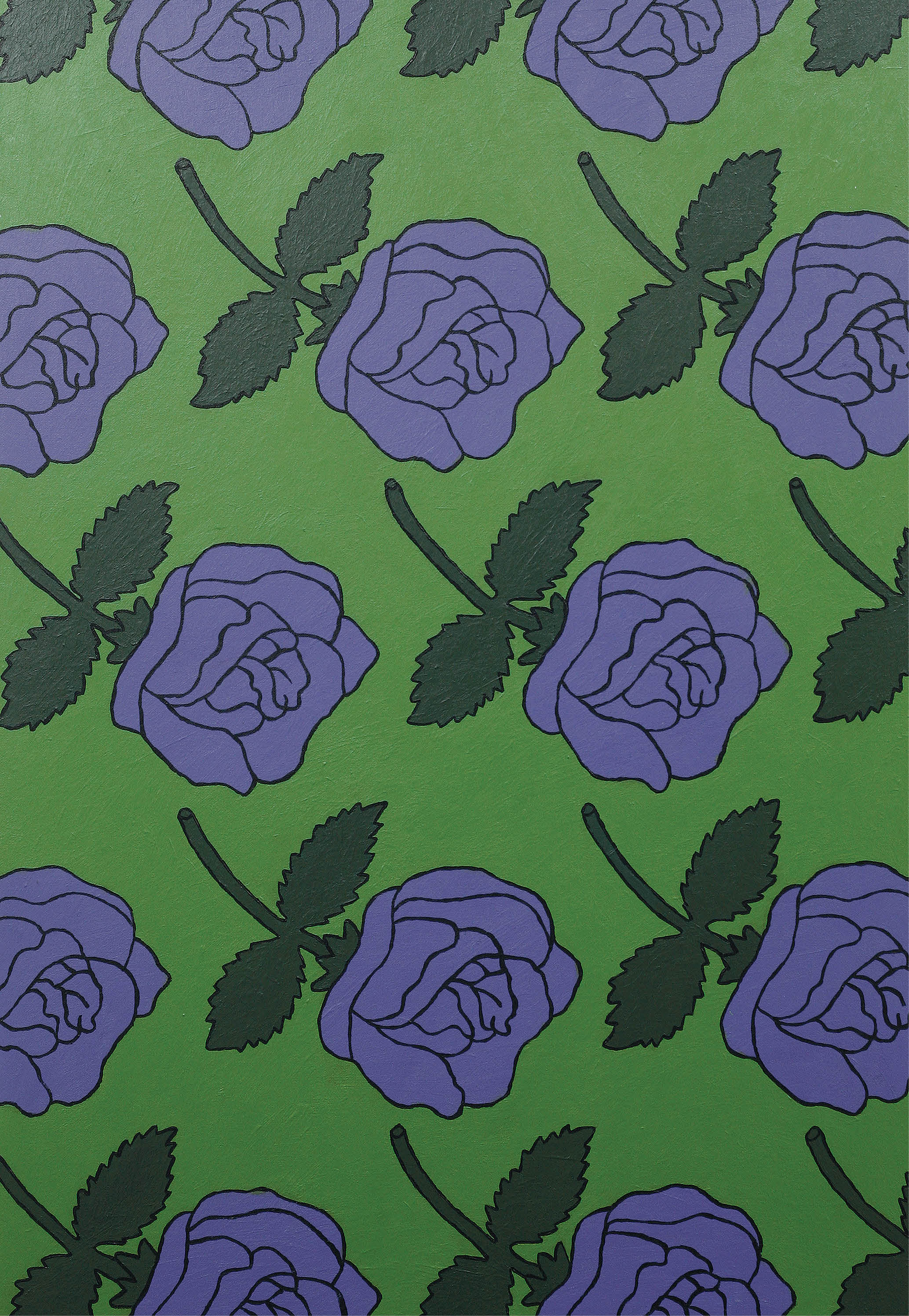

A series of floral paintings lack an overt crassness of Matthew’s previous works, presenting a refined ‘badness’. Taking their names from domestic paints — such as Sunset Sparkle, Fresh Air, and Earthly Delight — each painting takes as its starting point a certain flower that repeats across the canvas to create a pattern. They exhibit sensibilities of camp such as reduced decorative forms and an artificial feeling. Most commercial art galleries have a represented artist who paints flowers: a safe sell, as flowers fit within an easy lifestyle home décor taste. But Matthew’s flowers are ambiguous in taste, hovering on the cusp of the lurid and the pretty. The uneven layering of paint and their repetition across the canvas is almost kitsch, but they are nevertheless flowers with colourful cheer and sentiment.

Sensibilities of camp and bad taste come together in Matthew’s works to form art that can be offensive but is nevertheless playful and pleasurable. Viewing them is like listening to a verbal joke. Their hard lines are akin to the formation of words, sitting close to caricature, the brevity of a story stripped back, and a simple play with words. An essential part of jokes is their social nature: they are shared between individuals. Matthew’s works are doubly funny in that we laugh at the art object — quite possibly alone — and they laugh at us through their depiction of social conventions of tastes and norms housed in camped vulgarity.

Zara Sigglekow is a Melbourne based arts writer, curator, and administrator.