We were sitting in a dark lecture theatre when it happened. I can’t believe it happened. My hand was raised. The moderator looked at me in acknowledgement. And then it happened. I asked Marcia Langton a question.

I said, ‘Can you speak to the humour in Brook Andrew’s work?’ She replied with a deafening silence, which gave me time to wish a gaping chasm would open up beneath me and into which I would fall. Then she said, ‘It’s not humour, it’s satire’. And the moderator said, ‘And that’s time, no more questions’.

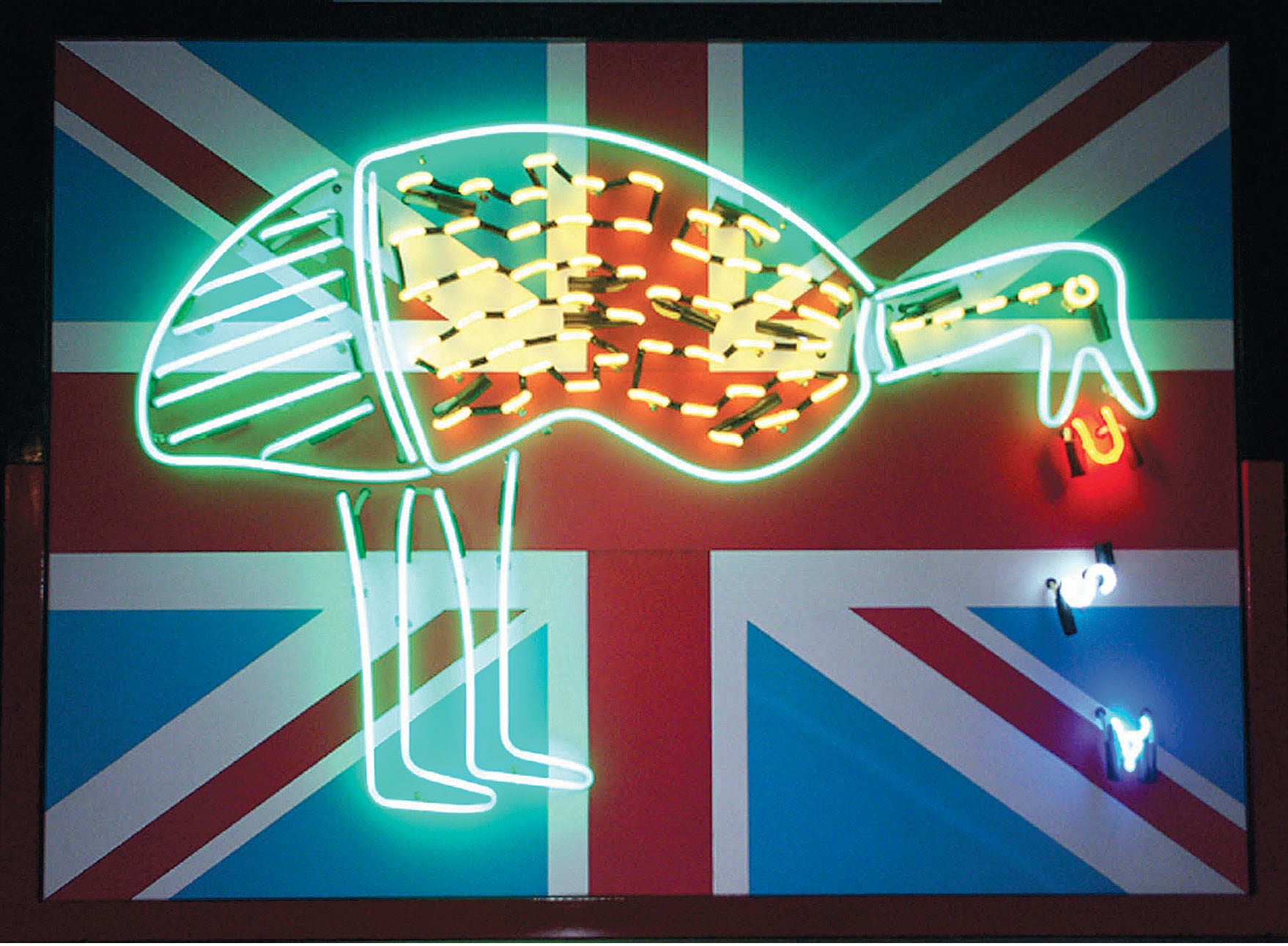

When my sphincter unclenched three hours later and I was able to reflect on her answer, I thought: yes, this seemed true of Andrew’s work, the works I found funny weren’t laugh out loud funny, but there was a wry satire that brought together the critical and the humorous. When I asked Langton that question I had been thinking of dhalaay yuulayn (passionate skin), 2004, which depicts a neon emu: the iconic Australian animal and representative avian on the coat of arms. It is emblazoned on the Union Jack, its head is bowed and the red white and blue coloured letters ‘U’ ‘S’ ‘A’ are tumbling out of its mouth. The symbols of each country are prominent and the ridiculousness of a regurgitating emu introduces an element of play and of absurdity to the work, we can laugh at Australia’s spewing of US rhetoric.

The emu is a reference to an image from a brochure for the 1955 formative Australian movie Jedda by Charles Chauvel.1 Chauvel’s film considers identity during the White Australia Policy era, the titular character is ultimately doomed to a violent death for following her ‘uncivilised’ nature instead of staying on the homestead with her adoptive white parents. Jedda was advertised as a thrill for white audiences, a chance to view ‘primitive savagery.’2 In this sense the emu becomes a symbol of perpetuating Western cinematic conventions; catering to the gaze of a white audience consuming the archetype of the exotic savage, the use of neon feeds into this as a reference to modern advertising and consumerism.

But things are not necessarily as they appear in Andrew’s work. At the edges of the board are the colours of the Aboriginal flag, black over red, and the body of the emu is yellow creating the sun that sits in the flag’s centre. Art historian Kate MacNeill discusses Andrew’s ability to disrupt and undermine the colonial gaze in works such as I split your gaze (1997), an ethnographic portrait separated down the middle so that the eye can never resolve the work and the subject can not be contained. Though not within the realm of archival photography, this method of Andrew’s seems relevant to dhalaay yuulayn, as though the presence of the covert flag denies a whole reading of the work; to focus on one is to ignore the other.3

The humour in Andrew’s work sneaks in without announcing itself, it is stealthy and undermining, it isn’t humour, it’s satire, it does not excuse the offence but draws it out into the light of day, it says: this is ridiculous.

Is it okay to laugh?

When I first saw Bindi Cole Chocka’s series Not really Aboriginal (2008), I wanted to laugh. I wanted to laugh because it was so absurd and so shocking. It was also very uncomfortable; maybe my laughter was about easing the tension, especially as a white person looking at blackface.

In this series of the artist and her family, the sitters have their faces painted charcoal black and they look directly at you with a confronting deadpan delivery. The blackface is a reference to the minstrel figure which emerged in American popular culture as a comical stereotyping caricature of blackness.4 It is a shocking taboo but it maintains a presence in contemporary Australian popular culture as well, we see it in golliwogs, revived in Hey Hey It’s Saturday performances and children attempting to ‘dress as’ their favourite football players. The title, Not really Aboriginal, comes from a phrase Cole Chocka would sometimes hear when she made people aware of her Wathaurung heritage — people were reacting to the colour of her skin, she wasn’t ‘dark enough’ to be Aboriginal. She found this disbelief jarring, having grown up with a firm sense of self, instilled by her grandmother. Rather than her Aboriginality being culturally and self-defined she found it was vested in historic concepts of skin colour, as though authenticity was bound up in measurements like half-caste, quadroon and octoroon.

Cole Chocka’s photographs draw on a specifically Australian set of reductive motifs; that Aboriginal people have dark skin, red headbands and live dysfunctional lives in remote settings.5 She posits this as the ‘authentic’ image of Aboriginality and the critique is brought into focus by her juxtaposition of the expectation with the reality of contemporary middle class family life. The scenes are mostly inside the domestic family home with carpet and drapes, floral couches and shoes off inside the house. The difference in tone is jarring and begs the question, is this what you really expect of me?

Not really Aboriginal works well as an answering back to racism because the satire arises from Cole Chocka’s subjective position. This is something Marcia Langton talked about in her influential essay Well I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television, where she wrote that stereotypes of Aboriginality are transmitted when cross-cultural contact is lacking and images imagined by colonial forbears are recirculated. It is only when people interact in situations where both are subjects rather than objects that both parties can test their preconceived notions against incoming information and readjust their beliefs.6 Thinking about the source of humour, who is making the joke, is an important ethical consideration. When I look at Cole Chocka’s work and I laugh, I know that I am laughing with the artist, not at her.7

Who is it for?

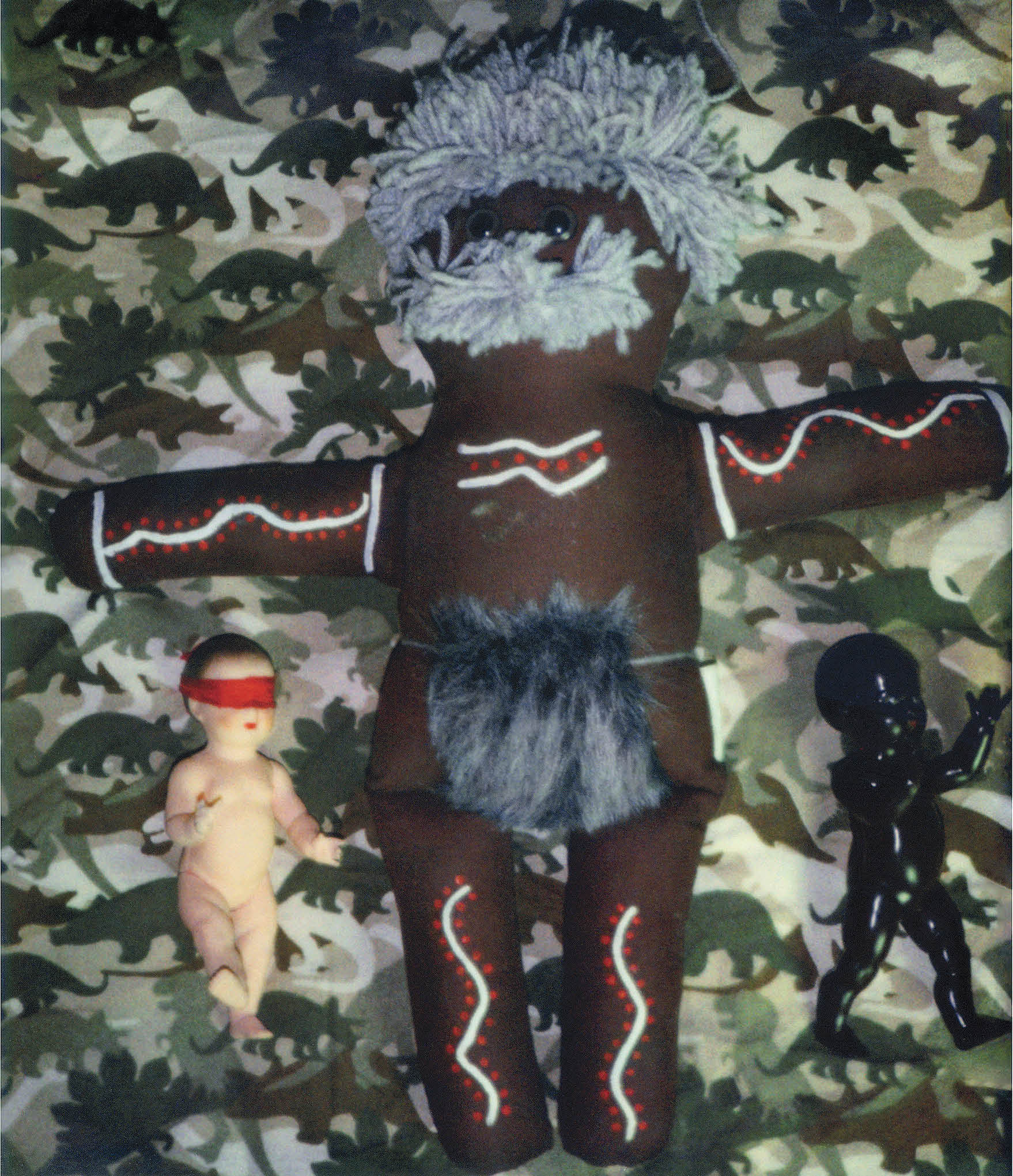

Hear come the judge (2006), is a lo-fi image of a cloth doll of an old man, naked but for his bushy grey beard and furry loincloth and bearing ‘Aboriginal style’ designs. It is a ridiculous object and a typical example of Destiny Deacon’s playful sense of humour when it comes to kitsch.

When I first read the title I thought it was referring to the doll as a God figure that comes to judge us in the end of days, posed as it is, like Jesus on the cross. But then I showed a draft of this article to my dad who doesn’t know how to use track changes so insists on calling me on the phone to go through a document, and he told me that ‘hear come the judge’ was a phrase that got used in a sketch comedy show called Laugh-In in the 1960s and 1970s. Thanks Dad. It was popularised by various singers, most prominently Pigmeat Markham, as a comical one-liner used in a mocking courtroom scene. That last part I looked up myself, but it’s from Wikipedia, sorry un mag.

If we run with the religious theme though, the plastic dolls beside the central figure could be angels, as dolls sometimes appear in Deacon’s work as angelic figures watching over people of earth.8 The white doll is blindfolded, recalling the allegorical figure of Justice (or maybe it is just unseeing) and both plastic dolls have been articulated into poses that resemble dancing. The scene is absurd and comical, the childish innocence of the central doll clashes with the consumption of reductive stereotypes it represents.

Deacon’s work sticks with me because she was one of the first artists that made me realise art wasn’t always ‘for me’. That’s not to say she polarises her audiences, but there is definitely a key element of humour to some of her work; those who get it and those who don’t. Contemporary artist Jens Haaning broadcasts Turkish jokes over loudspeaker in a square in Oslo creating a micro community of migrants who recognised and understood its humour. ABC’s Black Comedy has the thong-throwing mum, Blakforce — the culture police and the Tiddas. Saturday Night Live summed this condition up well when they had white cast members freak out while listening to Beyonce’s Formation, with cries of ‘maybe the song isn’t for us?’ while their black friends looked on, shaking their heads. A general audience can find enjoyment in all of these creative outputs, but the point is that they were made to address a marginalised group within a predominantly white environment.

Deacon has her black dollies, items that speak to a particular experience of being black and growing up in Australia in the 1960s and 1970s, when these toys first appeared. She has long collected items of ‘Aboriginalia’ as she wants to ‘save them from white ownership,’ and to give them a voice.9 In Hear come the judge the dolls assume a position beyond that of mute, ventriloquised plaything, they become extensions of the artist’s psyche, brought back into the fold of an Aboriginal subjectivity.

The art of Andrew, Cole Chocka and Deacon deals directly and specifically with the Australian condition, the way of living in Australia with its myriad ways of being and echoing waves of history that continue to push all of us forward into the future. These three artists take the historical and persisting consumption of racist narratives and turn them out in front of us, daring the audience to acknowledge the absurdity and the pain of this type of discourse. Their art bears witness to the power of satire to contain the tension between tragedy and comedy, it is a bitter laugh, but one that speaks to the strength to resist despite overwhelming cultural inertia.

Chiara Scafidi is an emerging curator and writer. In 2015 she wrote her honours thesis on the use of the mirror in the work of Gordon Bennett, she would go on to co-curate Gordon Bennett: Moving Images, held at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in June 2016.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, URL: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-09-28/bolt-found-guilty-of-breaching-discrimination-act/3025918