I speak from a position of solidarity with victim/survivors (I think about the temporality implied in this language and think ‘endurer’ may be more apt) past, present, and future. Those who have shared their stories, those who have not come forward and those who never will.

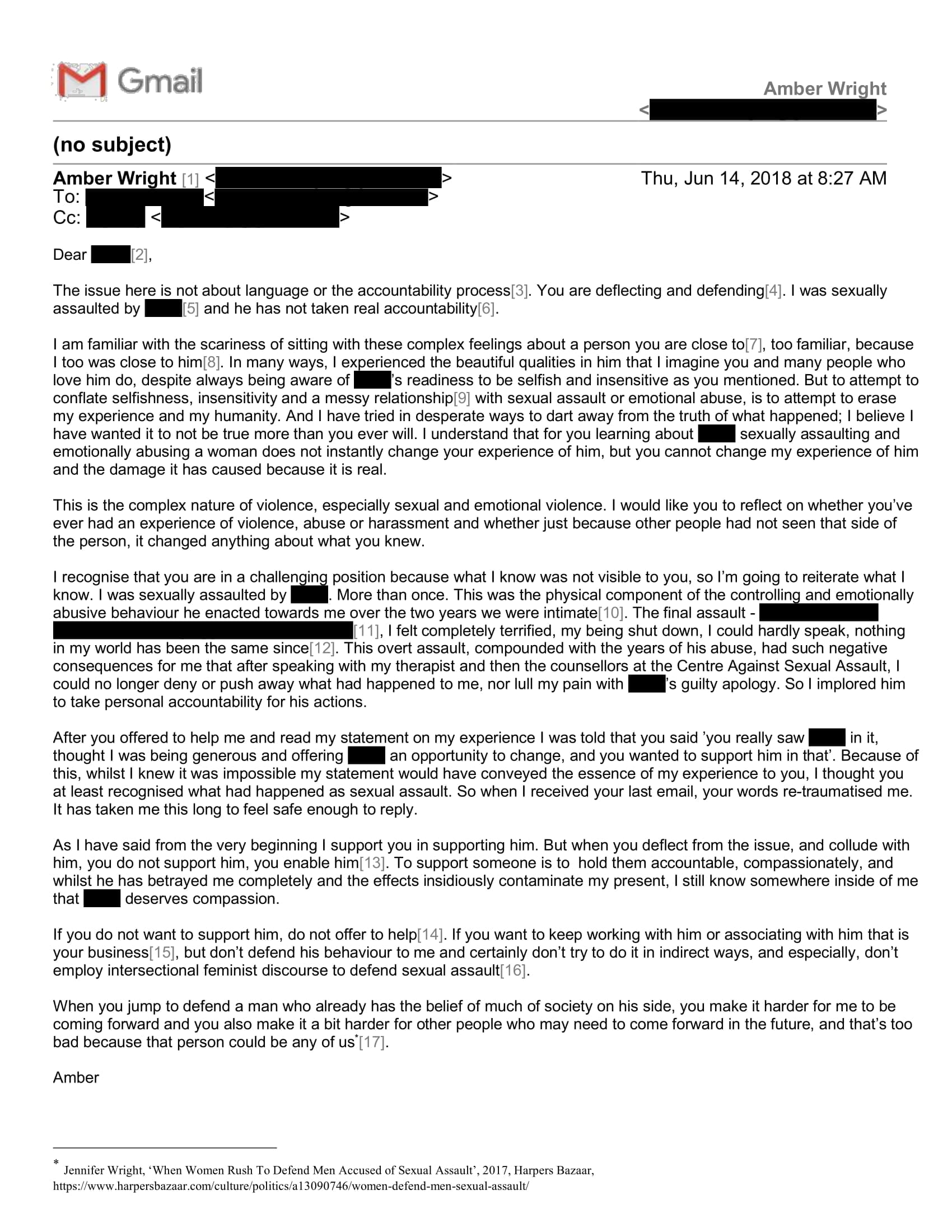

This letter was in response to news that this person was withdrawing her support from an ‘accountability process’ in which she had previously volunteered. As a close friend and creative collaborator of the ‘Abuser’, she was the key support in his rehabilitation.

Accountability processes are alternatives to state criminal justice systems that encourage education and healing as methods of justice. A facilitator of this process offered the ‘Abuser’ and his ‘Collaborators’ modes of support instead of isolation, as isolation is known to result in abusers moving on to a different community and continuing a cycle of abuse.

I want to speak to the conditions that have embedded harassment, assault, rape and abuse as an ongoing weight and pain in the arts. The ‘Collaborator’s’ choice to defend the ‘Abuser’, which came after a small repercussion to his career in turn impacted hers, serves as an example of how an abuse of power is enabled or reproduced.

Sara Ahmed’s extensive research on how arts institutions and communities treat complaints of sexual violence observes: ‘Domination works by presenting a dominant view as just another view (that someone has the right to express). An abuse of the system is part of the system.’

Defenders delegitimise accusers and close ranks around abusers by offering ‘opinions’ such as suggesting abusive behaviour was unintentional, implying that the accuser is partially responsible for the abuser’s choices and re-framing abuse as conflict. Rationalising, dismissing, minimising and silencing veils their defence of another’s abusive behaviour. Derailing abuser accountability is a common strategy for those invested in protecting an abuser’s power, to in turn protect the access to power their association offers them.

The person who abused me is a functional, friendly and institutionally funded man with whom I share a network of associations. Sara Ahmed asserts that ‘the figure of the “Abuser” as a stranger or foreigner is used by the system to run the system.’

While the ‘Abuser’ was initially defensive and changed his story multiple times, as is typical, he had eventually agreed to be held to account for his actions, stating it was very important to him to do his best here and therefore requesting contact with the accountability facilitator. In their first meeting he agreed to meet regularly for twelve months. At this point I breathed — I felt as if the war was over.

He did not attend another meeting before he dropped out and informed me he’d gotten a lawyer.

Cognitive dissonance is commonly experienced when people find out that someone they are close to has been accused of abuse, especially sexual abuse. This mental conflict that occurs when beliefs or assumptions are contradicted by new information often persists to varying degrees for those who remain close to the person who caused harm, until it is holistically addressed. An inability to integrate sexual violence is sustained by systematic silencing and normalising of it in our society, and the perpetuation of related myths. Judith Herman in Trauma and Recovery writes: ‘It is very tempting to side with the perpetrator as all they ask is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil. The victim, on the contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of pain. The victim demands action, engagement and remembering.’

I too experience cognitive dissonance. I had been friends and discussed potential collaborative work with the ‘Abuser’ prior to us being in a romantic relationship. I had heard about his previous partners’ experiences of his harmful behaviours. He did not use overt emotional abuse — strategies of power and control such as gaslighting — until after we were intimate. Abuse escalates over time and in response to perceived loss of power and control over the other. As is common, the ‘Abuser’ enacted the worst sexual assault on me after I ended the relationship.

Abuse, within a relationship or not, is not a relationship issue. Abusiveness is always and only an abuser’s issue. Abuse within a relationship, especially once an abuser’s strategies for power and control over the other are resisted, may make the relationship appear ‘messy’ while at other times it is extremely well hidden by deception, isolation, shame and silence.

Like many survivors, I took a long time to emerge from the muddy water of abuse and succumb to reality. Sometimes it takes a very shocking tangible experience for you to snap and realise what has been broken all along. The moments in which I wholly feel the reality of the situation are the most devastating and difficult to stay with.

Publishing the banally violent specifics of him raping me is likely to be read as entertainment by those who haven’t been raped themselves.

My mum says that she saw something in me collapse. I saw my work collapse. The people with whom I used to share my work saw nothing. A few close friends who gathered round me saw something like me but absent, out of body, somewhere else, not eating so often, not sleeping so well, speaking of nightmares over breakfast, panic attacks in public, crying, numb, angry, kicking boxes, skin rashes under my eyes and all over my hands, complaints of chronic muscle tension, heart palpitations, leaving for and returning from therapy appointments, acupuncture appointments, doctor appointments, unable to work, loss of income, stuck at home, feeling unsafe in spaces I once moved freely, social retreat, grief. So much loss. So much shame. No one ever tells you how laborious healing is, how you will resent it, how utterly ‘boring’ your life will become.

I speak up and I feel sick, I shake, I want to punch something.

I don’t speak up, I feel sicker.

It is a specific kind of suffering for survivors to find their abuser at almost every event, an omnipresence at art openings, film screenings and every other space they can seek to spread themselves. Or to hear them referencing shared memories on the radio, but leaving ‘you’ out of it and, of course, the abuse.

The mobility of survivors decreases as the abuser’s expands. This in turn impacts whose work is represented within contemporary cultural production, whose ‘talent’ rises and whose presence disappears, and the subsequent discourse or, more aptly, silence.

Working with, employing or promoting the work of a known abuser enables them to gain access to further power and control, which they can then in turn abuse. Statistically, abusers will abuse again unless they successfully do extensive work to change the attitudes and beliefs that lead them to harm others. The abuser will not create the opportunity to confront their problem and change without incentive.

Elvia Wilk’s article ‘No More Excuses’ discusses how we must work to uncouple abuse from power in the arts, and in ‘The Grammar of Work’ she advocates for ‘punishment in the form of preventing living abusers from continuing to benefit from their work (noun) when their working (verb) involves abusing (verb).’

Choosing who you work with and whose work you lift up is powerful. When you continue to collaborate with an abuser rather than encouraging them to step back and take responsibility for their harmful behaviour towards others, your silence is taken as endorsement of the behaviour.

At the Survivor Support Group I am attending weekly while writing this piece the signs on the wall read ‘Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim’ and ‘Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented’.

How does the script of defenders delegitimising the accuser and closing ranks around the abuser function in the arts where many things depend on unwritten hierarchies, gatekeepers and gossip?

The ways in which we relate to abusers and survivors, and orientate our associations and collaborations, has the power to conserve or stem the culture of abuse embedded in the arts. This is starting to go both ways. There has always been very real rewards for continuing to align oneself with powerful, abusive people and many people of all genders continue to do so, reinforcing the operative values of the system so they may find themselves a seat at the table. However, an increasing number of people are organising their collaborations, businesses and associations according to values that refuse that behaviour. For these people a key criteria in choosing who to work with can be not only that they are not known to be abusive but that they also are not currently collaborating and colluding with people known to enact such behaviour. All of our careers are impacted by who we choose to work with and for many it may become no longer advantageous or ‘worth it’ to work with with abusers.

In its overlap with academia, the arts has much to learn from recent discussions in response to the accusations of abuse against New York University (NYU) professor Avital Ronell:

‘A culture of critics in name only, where genuine criticism is undertaken at the risk of ostracism, marginalization, retribution — this is where abuses like Avital’s grow like moss, or mould ... funding, jobs, and prestige are doled out to the most obedient and obsequious.’ -- Andrea Long Chu

In a culture of toxicity and its consequences, everyone is implicated. Often we are in interchanging roles or playing more than one at a given time.

In the arts the way we relate and orientate our associations and collaborations offers an opportunity to enact a material structuring of power. Current asymmetrical power structures, within which abuse flourishes, are enabled and reproduced by defenders of abusers, their artistic collaborators and all bystanders that remain complicit through silence or neutrality. Whilst some may fear the implications of speaking up, I would argue for working together through uncertainty, towards the paradigm shift that is already underway.

Amber Wright is an artist living in Narrm/Melbourne.