Prior to the most recent performance (or performative exchange) of Illusions of Self Motion at the National Gallery of Victoria in June 2018, Brook Andrew asked trawulwuy art historian Dr Greg Lehman, myself and current performance collaborator Ben Opie to discuss the connections between Illusions on Self Motion with Brook’s own work 52 Portraits and Vox: Beyond Tasmania. Greg framed the context well in his opening comments, which I include here:

‘[This is] difficult and challenging material, because it relates to the activities of scientists and scholars in the 19th century who often built their reputation and used as their professional currency in trade the ancestral remains of my ancestors, and equally across the continent of Australia the removal of Aboriginal skeletal remains to institutions - most often in the British Isles and Europe. Brook’s work ‘52 portraits’ includes images of unnamed individuals from across the globe, based on 19th century postcards, which were a secondary product and commodification resulting from the trade in artifacts of scientific racism. The histories and identities of these people are absent from the archive. They are removed by the act of collecting, which in itself is a powerful metaphor for the colonial processes of containing an exoticized ‘Other’. These individuals are disappeared, despite their apparent documentation by photography. They’re left in a state where often it’s only family members, who - if given the opportunity - might recognize their own likeness or the likeness of their loved ones in these faces. And might possibly rescue and re-humanize them. I think this is one of the things that Stéphanie’s work seeks to do.

Brook commissioned Stéphanie to create a requiem: Illusions of Self Motion to accompany his work that is now held in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. The photographic portraits are accompanied by a sculptural work called Vox: Beyond Tasmania. This sculptural work is inspired by a volume of the ‘Transactions of the Royal Society of Victoria’ which was published in 1909 titled 52 Tasmanian Cranium. It contains drawings of the skulls of Tasmanian Aboriginal people held by private and institutional colonial collectors and published by the anatomist Richard Berry. Vox is a kind of wunderkammer, containing curiosities including drawings of skulls, a partial skeleton and human skull, photographs, diaries, glass slides, a stone axe and Wiradjuri shield drawn from Brook’s own heritage. These objects like the portraits are muted testaments to lives that have been silenced in the act of scientific collection. Their voices overwritten by the desperate efforts of scientific racism to establish European superiority over the diversity of human culture encountered across the globe. Vox is intended according to the artist to give voice or to play out the stories of Indigenous lives and to quote Brook, open our hearts to a 21st century memorial.

Requiem to commune ... 52 Portraits discussed above are screen prints on silver-coated canvases. The individuals represented are unnamed and without biography. Stately importance emanates through each person’s ethereal glow. 52 Portraits and Vox: Beyond Tasmania represent complex issues through flesh and bone. In some ways, Illusions on Self Motion becomes a voice, speaking to this constructed body.

Looking at this body of work, this work of bodies, I questioned how I could even start to approach a response and be respectful in doing so, indeed if it’s even right for me to approach it at all. I am indigenous to my own heritages but not to (almost all of) the heritages that the work speaks about and displays. There were signals to make this action and try and engage, although my initial gut reaction was to say no. It continues to be a lot to deal with, and in many ways that’s necessary - we should be sensitive in navigating projects that reference both colonial atrocities and cultures other than our own.

Signs & synchronicity ... The day I met Brook to speak about the work, happened to also be the first day of Kwibuka, the Rwandese mourning period which begins on April 7. Every year we commemorate the 100 days of genocide from 1994, in which time close to 1 million Tutsi were killed.

So of all days, the day we met was the day I entered the mourning period. It was unavoidable, our schedules were such that it was the only date for a while that aligned us in the same place and time. Brook showed me the first of the 52 portraits that he’d completed as an indication of what they would look like, as well as going through items of the archive that would go in Vox (these archival items were on show in Colony: Frontier Wars at NGV: Australia earlier in 2018). When he unveiled the portrait, my whole being switched to yes, I have to do this. I recognised the portrait to be my countryman. The source of his image, a colonial postcard,described him as a ‘Belgian Congolese man’. However, being from the western border of Rwanda with Congo, I recognised the amasunzu hairstyle, the adornment and bead pattern he was wearing to be of my people. Of all days, of all the portraits... it seemed too synchronicitous to ignore. It was one of many signs the ancestors were saying this is something I needed to do. I was to write a requiem not only about unidentified Aboriginal and world Indigenous peoples referenced in the exhibition, but about my own people, and those who still face cultural genocide daily, in all its inglorious forms.

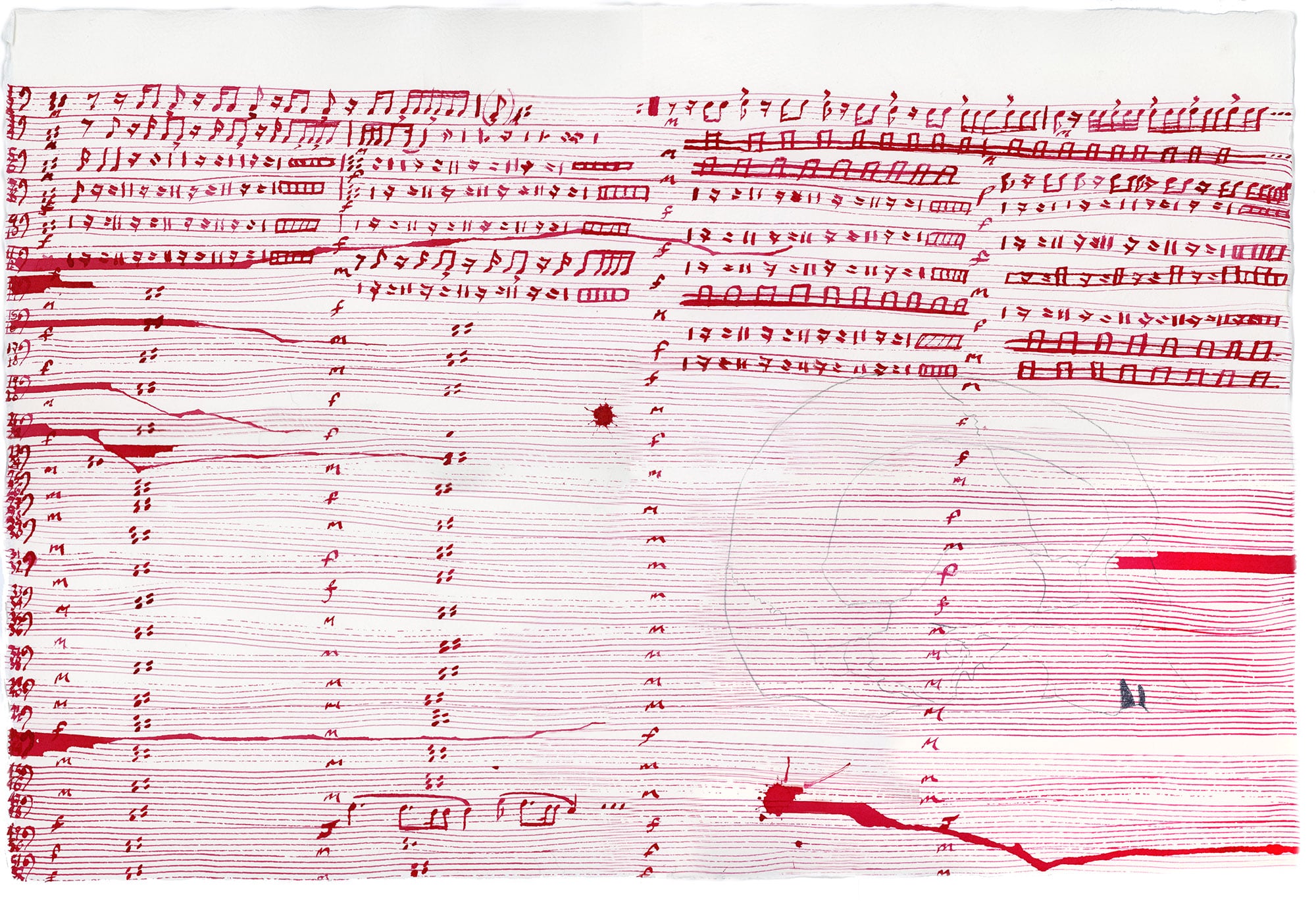

Collaborating with artists, artefacts and erasure led to the composition of a requiem with this graphic score.

The geography of ‘space’ ... Being neurodiverse, my daily lived experience means I’m comfortable with abstraction, ambiguity. It makes me a lateral thinker, inquisitive, patient and empathetic. But one thing is set for me in the presentation of this graphic score: it is not open for performance. You, the reader, do not have permission to play or perform it. In developing reference points for the creation of the work, it goes without saying that strict rules arose to govern its performance. The piece is only ever shared when an opportunity to speak and contextualise the work is available, to prevent it from being received as a musical moment of entertainment.

With no golden-ratio derived high point and cadential release, the music is reflexive to the rising and subsiding breath of both performer and listener. Each bar has an open length, and therefore the duration of the work is flexible - this empowers performers with an improvisatory freedom that necessitates the insertion of their own emotion to convey the work successfully.

This iteration of the conversation opened with Greg’s words, and concludes (or pauses) with those from conversation with my recent collaborator, Ben Opie.1 One of Australia’s foremost oboe and cor anglais players, Ben is also a composer and artistic director working at the genre-busting edges of classical and exploratory music.

We have talked through this work being a discussion about, rather than a representation of, colonial actions and the peoples affected by them. As a performer of oboe and cor anglais you have the option to play works from western art music composers who wrote on behalf of people. In this instance, through our conversation you know that my work is very opposed to that.

At times Indigenous and world Indigenous artists are expected to be representatives of our cultural groups. As an Anglo descended white male in Australia, for some audiences it might be problematic seeing you perform a work that references indigenous content and colonial practices of scientific racism. While I can see why for some that would be the case, I equally feel that’s why the approach of this work is as a dialogue rather than a representative voice. I also think that’s where the discussion comes around what I prefer to call ‘moving together’. I know lots of people use the term ‘moving forward’ - but I don’t think that people can or should be told to move forward on certain issues. That also assumes a linear sense of time, but that’s another story. Whenever there’s trauma big or small, it’s inappropriate and unhelpful to tell someone to move forward from it. What I try to do with the style of work I create is to find ways of ‘moving together’, in both senses: interpersonally, and developmentally. I think that’s more productive, and why I was so interested in collaborating with you on the presentation of this musical discussion. How do you practically intend to work together within the society we live in, given its glaring history? I think at this point in time, within Australia, there’s still a very binary discussion around colonial histories, cultural identities and nationality.

‘I’m scared and I’m white and I don’t know’ is the wall that gets put up. That’s what I feel like other people are thinking: ‘better that I just don’t say anything as I might get stuck, so I’ll just let someone else sort all of that out’.

Yes. In a western context, Australia is a relatively teenage country. From observance and research abroad, a more layered and nuanced dialogue is being held. So it concerns me when I hear the ‘black/ white = bad/good’ (and vice-versa) trope being the binary basis for these conversations: that’s fighting one paradigm with itself, and it doesn’t work.

Performing work like this onstage is not like reading a speech - there are so many more variables at play. Particularly with the sensitivity of this work and the nature of the instrumental setup, it takes time to test and finesse so many technical aspects. On top of that, you need space to focus, be present physically and emotionally so that you move beyond the mechanics of performance and connect.

It’s important to talk context around the score. You know something that comes to mind is the one melody that appears in the score - we talked about why those notes are in there and how they are relevant. Just looking at the score, until you spoke about it, I wouldn’t have necessarily focused on it as much as I did.

While creating this work, I had vivid dreams of both Tasmania

and the people in the 52 portraits. The only tune in the score appears in the bar of music relating to the one portrait of a smiling child. The melody appeared in one of those vivid dreams the child was humming it. I felt a type of guidance as my brain was clearly working through these things as to how I would approach finding sound and textural space that could be a conversation with the Vox: Beyond Tasmania and 52 Portraits. Yet there’s a balance of how much of my neurodiverse received sounds and experiences I put into something, as I’m mostly research-based in my practice. I don’t want to just make work from my autosensory experience.

Outside of me talking to you about some of these elements transcribed in the score, what are your sensory experiences and thoughts of it from the eyes of a neurotypical musician?

The colour is affective. With red I’m drawn to thoughts of blood. And all of this keeps on coming back to fact that we’ve spent time together discussing the symbolism of aspects of the score. Knowing the music stave calligraphic nib you used in the score and seeing you use it - I can hear the sound of it scraping against the paper. There’s a friction there. In my mind there’s a prominent sound of the dragging of the nibs over paper. That friction combined with the content and the colour - everything becomes tight, clenched. Knowing that you’re dipping into this red, it has a feeling of tension.

An iteration of Illusions on Self Motion with Stéphanie and Ben can be viewed and listened to via kabanyana.com.

Notes & Further Reading In An Unending Conversation

Richard Berry et. al., ‘Dioptrographic tracings in four normae of fifty two Tasmanian crania’, Transactions of the Royal Society of Victoria, Volume V, part 1, 1909.

Marcus Bunyan, ‘Un/settling Aboriginality, Art Blat, 2013. www.artblart.com/2013/07/11/textunsettling-aboriginality-dr-marcus-bunyan-exhibition-brookandrew-52-portraits-at-tolarno-gallery-melbourne/

Nicholas Forrest, ‘Composing a requiem for Brook Andrew’s 52 Portraits’, Blouin Art Info Australia, 10 and 16 July, 2013.

Gregory Lehman with Stéphanie Kabanyana Kanyandekwe and Ben Opie, Q & A prior to Illusions on Self Motion performance in Confronting The Frontier Wars: International Perspectives, a public programs event at the National Gallery of Victoria, 30 June 2018. www.ngv.vic.gov.au/program/confrontingthe-frontier-wars-international-perspectives.

Ian McLean, ‘Post Colonial: Return to Sender’, 1998. This essay was delivered as the Hancock lecture at the University of Sydney on 11 November, 1998 as part of the annual conference of the Australian Academy of Humanities which had as its theme ‘First Peoples Second Chance Australia In Between Cultures’. www.australianhumanitiesreview.org/1998/12/01/post-colonial-return-to-sender/