I was sprinting when I first heard Hannah Weiner’s voice. I’d developed a habit of running along the Merri Creek and, instead of listening to music, I would listen to audio recordings of poets reading and talking. I’d picked the recording almost at random from the PennSound archive, having never read her work before.

It was a recording of a performance of Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journal (1978). It opens as the book does — Weiner reads:

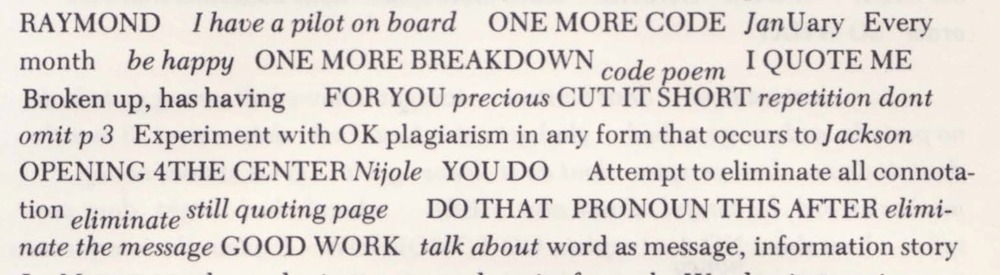

I SEE words on my forehead IN THE AIR on other people on the typewriter on the page These appear in the text in CAPITALS or italics

Weiner tells us that she will read the text that appears in regular font (her own voice), and Sharon Mattlin and Peggy De Coursey will read the seen words, words that give orders (CAPITALS) and words that make comments (italics).

The introduction is brief, thirty seconds maybe, after which the performance dissolves into some kind of anxiety- inducing, lusty chaos. The score of voices is fast, loud, urgent — each a source of constant interruption. This recording, labelled ‘March’, runs for twenty-six minutes and forty-eight seconds, and there is little room for pause. About twenty minutes in I remember a branch hitting my forehead, at which point I had forgotten I was running at all.

Both listening to and reading Clairvoyant Journal is disarming. It is the first in a number of books that Weiner wrote clairvoyantly, a method she called ‘clair-style.’ Weiner saw words everywhere, in all sizes, on her apartment walls, on clothes, surfaces, on her own and other people’s foreheads. Alan Sondheim recalls meeting her and Weiner declaring the word ‘poison’ was written on his head;1 C. A. Conrad retells a story from Eileen Myles of Myles at a party with Weiner, Myles thinking, ‘I wonder if she sees words on my forehead right now? Weiner looked at [Myles], walked across the room and said, “I see no words on your forehead, Eileen.”’2

This clairvoyance was understood by many to be a symptom of Weiner’s schizophrenia. However, a diagnostic reading of Weiner’s work is one she actively refused; disability and mental illness are not terms Weiner identified with. In denying a pathological reading of her work, it can be argued that Weiner carved out a space for a new approach to reading poetry. In refusing to be read as a disabled text, Weiner also actively refuses the ‘abled’ text and therefore the ‘abled’ reader, thus working towards an eradication of the disabled/abled hierarchical binary.3

While accounts from many often detail Weiner’s struggle to take care of herself, or to solicit care from others,4 a care for language as a material thing that might be cradled, disfigured or even broken, is central to Weiner’s legacy. Hannah Weiner was clairvoyant and I believe her. In accepting this as Weiner’s reality, what we’re forced to do as readers is to address our own relationship to language.

For Jacques Lacan, human-subjects are comprised of a Borromean knot consisting of three orders — the Real, the Symbolic and the Imaginary. For Sean Braune, Hannah Weiner’s relationship to language is best understood as an ‘experience of language [that] is material and extreme,’5 as an object that exists in the world. Braune goes further, making the link between Weiner’s relationship with language and Lacan’s Real. For Lacan, as cited by Braune, the psychotic’s experience of language is one that comes too close to the Real, a state that we lose direct access to after becoming speaking subjects because ‘it is forever apart from the cognizance of the barred subject.’^6 When we enter language, so too do we enter the realms of the Symbolic and the Imaginary, thus access to the Real is always mediated by these other orders. The Real is both an effect of the presence of language, and that which cannot be signified or integrated into the Symbolic. Importantly, the Real is not something that exists ‘out there’ without language, it exists because of it — it is the saying

that produces the unsayable. While the difficulty of trying to express the Real is also telling of its nature it is, as Lacan tells us, always ‘in its place; it carries its place stuck to the sole of its shoe, there being nothing that can exile it from it.’7

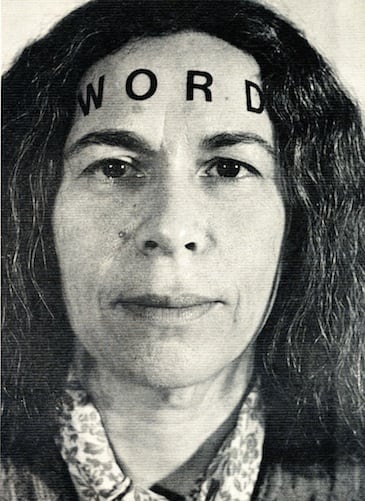

Weiner’s experience of language as an object, as a material thing that appears in her life and on the page, sits in this dialectic of the Real. Here words can never truly signify the thing in and of itself; instead they are their own objects that express themselves as they wish. Weiner’s work forces us to flirt with the Real as a state that exists because of the rupture brought into play by the Symbolic and Imaginary orders. When ‘word’ hovers above Hannah’s forehead, it becomes disembodied from its chain of signifiers — now what else could it mean but Hannah?

**

In disordering the ostensible ‘order’ of language, Weiner makes us aware of the impossibility of such an order in the first place. While we can attempt to make ‘sense’ of Weiner’s work, we’re faced with having to break down regular structures of reading and understanding. To read Clairvoyant Journal in a linear fashion, we’re faced with continual interruption:

To isolate each font, each voice, to attempt to read it in sequestration by removing the ‘noise’ of these other two voices, we’re faced with a similar dissolution of logic. Scanning the page, there are repetitions; it’s possible to form collages or constellations of meaning. But to approach the text in this way could be beside the point. In presenting us with a torrent of language removed from everyday function, we come up against the extent to which language shapes not only how we move through the world, but also our sense of being. In revealing the words that dictate her own actions, and in showing these words to be flawed structures that don’t always do as she intends, Weiner also reveals how behind these words there is always something unsayable (the Real). Writing on the relationship between being and appearance, Hannah Arendt argues:

conceptual metaphorical speech is indeed adequate to the activity of thinking, the speech of our mind, but the life of our soul in its very intensity is much more adequately expressed in a glance, a sound, a gesture, than in speech ...8

Weiner solidifies this, making us aware not only of what language can do, but also of what language fails to do.

**

In Clairvoyant Journal Weiner calls friends, has sex, shops, goes to the doctor, goes to concerts, worries about money, masturbates with the window open, goes or does not go to parties, reads, meditates, eats, writes. Here we come up against what Davy Knittle calls ‘rigorous dailyness,’9 Knittle argues that in observing this ‘rigorous dailyness’, we’re forced to identify the kinds of daily life traditionally exposed to us through art; through Weiner’s work we get to ask the question, ‘who gets to have a daily life and what gets to be a part of it ...’^10 Clairvoyant Journal sits alongside works like Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day (1982), identified by Elena Gomez as a writer contributing to a lineage of Marxist-feminist poetry11 — both are women who fought to make the labour of their daily lives visible, fought to unveil all conditions of labour under capitalism.

Clairvoyant Journal is an influential text both for the Language School and The New York School, but it doesn’t fit neatly into either. We might call it messy or chaotic, but this mess and chaos is part of what helps to locate the text’s politics; it is, in many ways, a mirror. Knittle argues that this is a book of its time:

this is mid 1970s, this is near bankruptcy New York City, this is heavily disinvested, chaotic ... non-functional New York City ... she’s interacting with a ... totally non-functional city government ... There is relationship between the disorder here and the excess and ... what the city looks like and sounds like at the time.12

Returning to Weiner’s rejection of schizophrenia, it can also be argued that Weiner is refusing to atomise or indiviualise the chaos of such a diagnosis. Mark Fisher, who wrote extensively on mental illness and capitalism, argued that mental health was not a private problem but a public one. Fisher states that to consider ‘mental illness as an individual chemico-biological problem has enormous benefits for capitalism: (you are sick because of your brain chemistry), and second, it provides an enormously lucrative market in which multinational “psycho-mafias” can peddle their dodgy drugs (we can cure you with our SSRIs).13 This model says nothing of causation — for Fisher, the causation is linked specifically to capitalism which he says ‘both feeds on and reproduces the moods of populations’^14 Fisher diagnoses capitalism itself as mentally ill: ‘capitalism is characterised by a lurching between hyped-up mania (the irrational exuberance of “bubble thinking”) and the depressive come-down (the term “economic depression” is no accident).’^15 The privatisation of stress and mental health, as Fisher calls it, is directly beneficial for capitalism because it avoids political or social accountability; if an individual does not overcome their own personal hardships, it is because they have simply not worked hard enough.

Reading Weiner and about her, I am comforted by the fact that she struggled to write. She is unwavering in identifying as a writer, but she also is lazy, she tells us so: ‘I want to write but I am lazy.’16 She writes through things that arrive, be that the words she sees or codes that simply need rearranging. Barabara Rosenthal gives her a notebook in 1989, a new year’s gift as encouragement to write. Rosenthal has ripped pages at different angles along a straight edge that she called ‘pagels’ and on them Weiner writes The Book Of Revelations, which was composed in 1989 and made available as a facsimile in 2011 by Marta L. Werner.

I feel lazy, too — mostly I hate to write. Hate its process. I like its bookends, the arrival of an idea, small moments of glory when something strikes on a walk, connecting two seemingly unrelated thoughts. And I like its conclusion, a moment when I’m faced with a rounded little object to hurl out into the world. Mostly, I continue because of those I write next to, who I read and who read me, who say strange and lovely things to me that I steal and put inside poems.

**

A lot of people don’t know who Hannah Weiner is, or have heard her name and not read her. She was a performance artist as much as she was a poet but what remains of this is mostly recollection. Her books are mostly out of print, but she is there. In 2014, Bat Editions published an edition of Clairvoyant Journal following the exact page design and format of Weiner’s. Eclipse, a free online archive focusing on digital facsimiles from small presses, has downloadable PDFs of a large number of works by Hannah Weiner. Charles Bernstein, the executor to Weiner’s literary estate, Patrick Durgin and Marta L.v Werner (among others), have also worked tirelessly on archival projects that make reading Weiner’s work possible.

Here, I’m reminded of the etymology of the word curator, which derives from the latin cūrā(re), meaning to care for, attend to. How important this is when thinking about who history has cared for, attended to, and who it has forgotten.

In thinking about this cūrā(re), it is also important that we attend to adequate critical reflection. Weiner’s work, continuing this clair-style, became increasingly interested in reflecting social injustice. Later works like Spoke and WRITTEN IN/The Zero One reveal Weiner’s involvement in fighting for Native American rights. However, there are ethical considerations to be made here, and Weiner’s approach deserves critical rigour. Weiner often maintained that many of her ‘silent teachers’, those that spoke to her through words and who she transcribed onto the page, were Native American, and while Weiner strove to back an Indigenous cause, she also risked othering and ventriloquising a minority she sought to support.

As Goldman argues, through this identification with Native American rights ‘she risks “the slippage from rendering visible the mechanism to rendering vocal the individual” (Spivak) – the danger of ventriloquizing the subaltern’.17

**

I think about Hannah Weiner a lot. Today I thought about her while filling out a Centrelink report. On her Electronic Poetry Centre author page, a digital archiving resource run by the University of Pennsylvania, there’s an old Radcliffe Questionnaire she filled out in 1974. It’s labelled ‘QUESTIONNAIRE FOR MEMBERS OF THE CLASS OF 1950’. It’s a boring piece of bureaucracy that Weiner fails to fill out in any way an administrative department would deem to be useful, but it’s a piece of writing I love. Throughout the questionnaire she tells us about her writing, not having enough money, going to parties, an abandoned career in lingerie design, seeing words, taking acid, psychic experiences, and again and again a love and commitment to writing poems.

The last section reads: ‘we appreciate your cooperation in completing this questionnaire. If you have further explanations about any of your answers please feel free to make them. Comments or suggestions about this questionnaire would interest us also.’ Hannah replies:

I want to explain further I WRITE with the words I see, get directions for my life, WRITE, what to do, buy CHEAPLY, who to see ETC. I have documented FIVE years of psychic experiences UNUSUAL and I would like to PUBLISH these works in BOOK FORM. NOT ENOUGH TIME to get the material edited BY MYSELF the words also fill out the questionnaire for me, partly, some CAPITAL letter words.

What should be a mundane bureaucratic filter for measuring success becomes a lucid and vibrant account of a relationship with words. All language is important to Weiner, and she reminds us that it is everywhere. Lacan tells us ‘I am not a poet, but a poem,’18 and Weiner tells us this too — she reminds us of all the ways in which we are not just writing, but written.

Melody Paloma is a poet, performance artist, editor and critic currently living in Naarm (Melbourne).

work of Hannah Weiner see: Patrick F. Durgin, ‘Psychological Disability and Post-Ableist Poetics: The ‘Case’ of Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journals,’ Contemporary Women’s Writing, 2:2, Oxford University Press, 2008. See also: Joyelle McSweeney, ‘Disabled Texts and the Threat of Hannah Weiner’, Boundary 2, 36:3, Duke University Press, 2009.

of Psychoanalysis, Jacques-Alain Miller (ed.) and Alan Sheridan (trans.), New York and London: W W Norton & Company Ltd, 1981, p. viii.