We’re not going to pull the death of the author on you again. No, not that again!1 —Claire Fontaine, Ready-Made Artist and Human Strike: A Few Clarifications, 2005While researching for this piece I came across a blog article seeking to verify the popular attribution to Pablo Picasso of the quote: ‘Good artists copy; great artists steal.’ The blog post traced very similar utterances to the likes of T.S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky among others. None however pointed towards Picasso, except for a perhaps incorrect attribution by Steve Jobs in a 1988 interview.2 The irony of the idiom’s misattribution was not lost on the writer of the article. I thought too of recently revisited allegations that Marcel Duchamp, the father of the ‘readymade’, stole the concept of his seminal Fountain from female friend Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, taking the credit and changing art history in his name.3 These instances of misattribution tell us how culture and myth is aggregated, as well as how voices are silenced or privileged along the way.

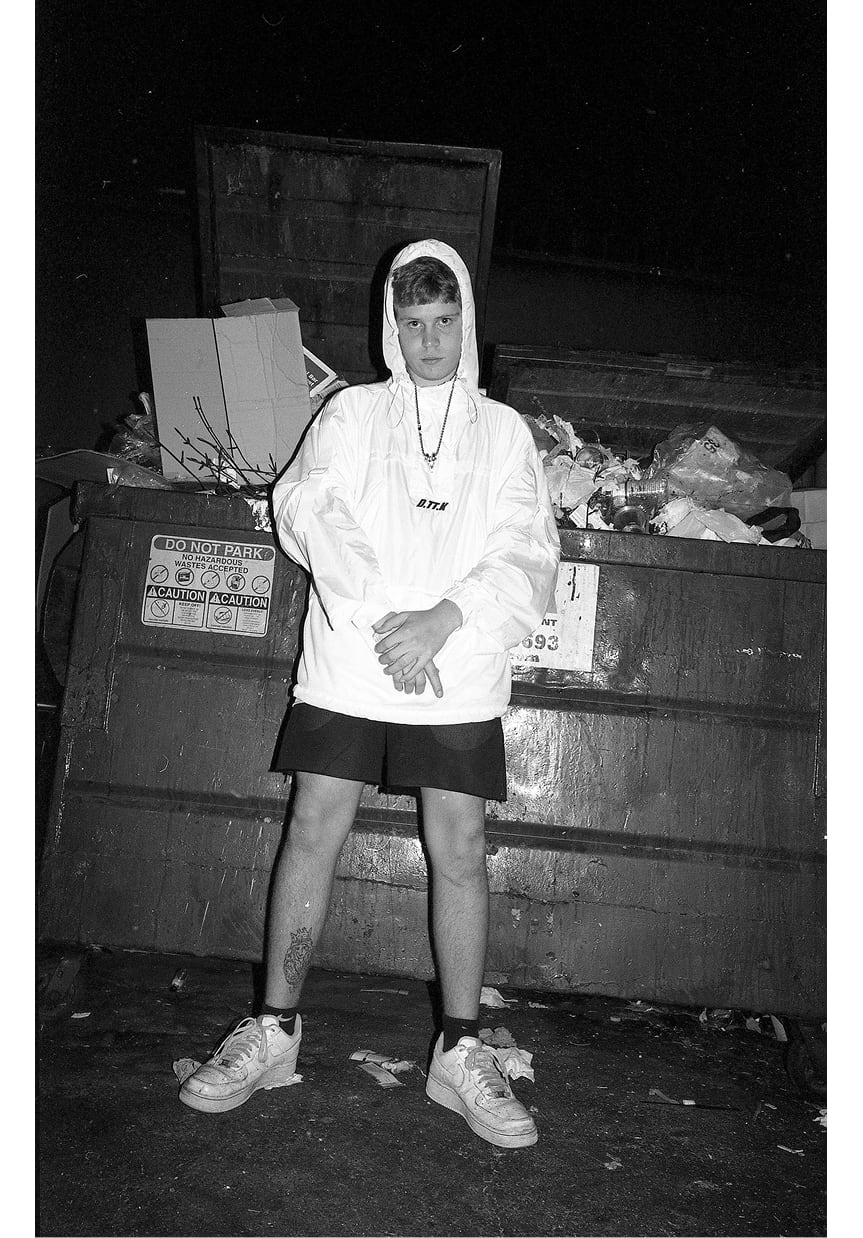

Yung Lean seems to have taken no small amount of inspiration in meme-worthy rapper Lil B from the San Francisco Bay Area. Lil B’s perhaps feigned amateurism contains sloppy lyrical delivery, extreme earnestness, strange subject matter and low-budget music videos released prolifically via YouTube. Lil B-as-meme reminds one of a similar fascination with ‘community access’ television as parodied by the likes of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! and archived by the website Everything is Terrible. In Lil B, we see a sort of critique of the community access mentality of the twenty-first century, where users of YouTube at once browse videos by musicians they aspire to be, then subsequently become producers uploading videos of their own. Lil B’s character embodies the rap fan and aspirant rapper come self-made internet superstar. Lil B’s style broke ground for an aesthetic of amateurism in online hip-hop and paved the way for the likes of Yung Lean. This young Swedish rapper could be more of a logical next step; nothing radically new, but simply the accumulation of stylistic interests belonging to a teenage internet user. Yung Lean and his group Sad Boys—together with another similarly minded collective Shield Gang—seem to be propelling this moment of young internet rappers into a subcultural movement.

The re-interpretation of cultural signifiers discussed above is at the heart of subcultural practice, as outlined most famously by Dick Hebdige in Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Hebdige opens his discussions relating to the prison memoir of Jean Genet and a controversy surrounding the police’s discovery of a tube of Vaseline in his possession. A ‘puny and most humble object’ in Genet’s words could come to signify something radical, in this instance Genet’s sexuality and a subsequent refusal of normativity.4 A safety pin, a tear in clothing, even once standard garments of a previous generation are adopted by the subcultures of Hebdige’s study (punks, mods, skinheads, teddy boys). In turn these signifiers become symbolically radical, as a supposed act of working-class resistance to a dominant culture, from which the subcultural youth have been alienated. Yung Lean’s work however does not seem at all a kind of cultural resistance. If anything, it appears an aggregation of cultural signifiers for the purpose of stylistic distinction.5

From Dadaist collage to Situationist détournement, the aggregation and re-contexualisation of cultural signifiers as a mode of practice has had a continued presence throughout twentieth-century art, often as a means to a politically conscious end. However something has changed in the aggregation of cultural signifiers with the internet. As Claire Bishop notes in her 2012 Artforum International text ‘Digital Divide’, mainstream culture with the internet is no longer one of a ‘society of the spectacle’ imposed on a passive audience. Rather, social relations occur ‘through the interactive screen, and the solutions offered by ‘useful art’ and real-world collaborations dovetail seamlessly with the protocols of Web 2.0’.6 Enter so-called ‘creative labour’ as a growing paradigm for consumption. When the attitude of ‘everyone’s an artist’ is pushed on consumers, with the global archive of the internet as the artist-consumer’s proposed palette, we can see the potential for both the problematic and the banal in liberalised image distribution.

It is not my intention here to critique singularly the instances of cultural appropriation in Yung Lean’s music.7 More so, I am interested in the platforms of consumption that seem to facilitate this. Martin Roberts has noted that the emphasis on stylistic distinction which subcultures foreground, creates the potential for ‘subcultural imperialism.’ On this topic he gives an interesting example of the Goa trance music community. In Goa trance the iconography of non-Western cultures are often used in an Orientalist manner, together with a model of global music festivals in ‘exotic’ locations that hypocritically ‘profits from and perpetuates colonial power relations and economic inequalities’ creating ‘carefully-policed enclaves designed to keep locals out’.8 In the new international colony of the internet, such problematic subcultural imperialism and cosmopolitanism is unsurprising. Social media services (like Tumblr and YouTube) hold a primary expectation on their users to parade their distinctions; stylistic subjectivities that now draw from increasingly disparate cultural signifiers, disconnected from their original context via the net. This is what David Joselit means when he talks of ‘neoliberal’ image distribution.9 Joselit’s terminology is not to be confused with the economic doctrine from which he draws the name—being a dogma of privatisation and entrepreneurial freedoms, unhindered by regulation from the State.10 It is however not surprising neoliberal economics have found a happy home in the internet start-up culture that this article is concerned with.

What is the impetus behind the push for users of social media services to present their subjectivities as innovative, unique and distinct? McKenzie Wark speaks of a new kind of working class in developed economies, a ‘hacker class’. The hacker class is expected by the ruling class of our time, who Wark calls the ‘vectoral class’, to be constantly innovative. He notes:

Yung Lean seems to have taken no small amount of inspiration in meme-worthy rapper Lil B from the San Francisco Bay Area. Lil B’s perhaps feigned amateurism contains sloppy lyrical delivery, extreme earnestness, strange subject matter and low-budget music videos released prolifically via YouTube. Lil B-as-meme reminds one of a similar fascination with ‘community access’ television as parodied by the likes of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! and archived by the website Everything is Terrible. In Lil B, we see a sort of critique of the community access mentality of the twenty-first century, where users of YouTube at once browse videos by musicians they aspire to be, then subsequently become producers uploading videos of their own. Lil B’s character embodies the rap fan and aspirant rapper come self-made internet superstar. Lil B’s style broke ground for an aesthetic of amateurism in online hip-hop and paved the way for the likes of Yung Lean. This young Swedish rapper could be more of a logical next step; nothing radically new, but simply the accumulation of stylistic interests belonging to a teenage internet user. Yung Lean and his group Sad Boys—together with another similarly minded collective Shield Gang—seem to be propelling this moment of young internet rappers into a subcultural movement.

The re-interpretation of cultural signifiers discussed above is at the heart of subcultural practice, as outlined most famously by Dick Hebdige in Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Hebdige opens his discussions relating to the prison memoir of Jean Genet and a controversy surrounding the police’s discovery of a tube of Vaseline in his possession. A ‘puny and most humble object’ in Genet’s words could come to signify something radical, in this instance Genet’s sexuality and a subsequent refusal of normativity.4 A safety pin, a tear in clothing, even once standard garments of a previous generation are adopted by the subcultures of Hebdige’s study (punks, mods, skinheads, teddy boys). In turn these signifiers become symbolically radical, as a supposed act of working-class resistance to a dominant culture, from which the subcultural youth have been alienated. Yung Lean’s work however does not seem at all a kind of cultural resistance. If anything, it appears an aggregation of cultural signifiers for the purpose of stylistic distinction.5

From Dadaist collage to Situationist détournement, the aggregation and re-contexualisation of cultural signifiers as a mode of practice has had a continued presence throughout twentieth-century art, often as a means to a politically conscious end. However something has changed in the aggregation of cultural signifiers with the internet. As Claire Bishop notes in her 2012 Artforum International text ‘Digital Divide’, mainstream culture with the internet is no longer one of a ‘society of the spectacle’ imposed on a passive audience. Rather, social relations occur ‘through the interactive screen, and the solutions offered by ‘useful art’ and real-world collaborations dovetail seamlessly with the protocols of Web 2.0’.6 Enter so-called ‘creative labour’ as a growing paradigm for consumption. When the attitude of ‘everyone’s an artist’ is pushed on consumers, with the global archive of the internet as the artist-consumer’s proposed palette, we can see the potential for both the problematic and the banal in liberalised image distribution.

It is not my intention here to critique singularly the instances of cultural appropriation in Yung Lean’s music.7 More so, I am interested in the platforms of consumption that seem to facilitate this. Martin Roberts has noted that the emphasis on stylistic distinction which subcultures foreground, creates the potential for ‘subcultural imperialism.’ On this topic he gives an interesting example of the Goa trance music community. In Goa trance the iconography of non-Western cultures are often used in an Orientalist manner, together with a model of global music festivals in ‘exotic’ locations that hypocritically ‘profits from and perpetuates colonial power relations and economic inequalities’ creating ‘carefully-policed enclaves designed to keep locals out’.8 In the new international colony of the internet, such problematic subcultural imperialism and cosmopolitanism is unsurprising. Social media services (like Tumblr and YouTube) hold a primary expectation on their users to parade their distinctions; stylistic subjectivities that now draw from increasingly disparate cultural signifiers, disconnected from their original context via the net. This is what David Joselit means when he talks of ‘neoliberal’ image distribution.9 Joselit’s terminology is not to be confused with the economic doctrine from which he draws the name—being a dogma of privatisation and entrepreneurial freedoms, unhindered by regulation from the State.10 It is however not surprising neoliberal economics have found a happy home in the internet start-up culture that this article is concerned with.

What is the impetus behind the push for users of social media services to present their subjectivities as innovative, unique and distinct? McKenzie Wark speaks of a new kind of working class in developed economies, a ‘hacker class’. The hacker class is expected by the ruling class of our time, who Wark calls the ‘vectoral class’, to be constantly innovative. He notes:

The vectoral class needs the almost-routine innovation. The existing commodity cycles demand it. As our attention fades and boredom looms, there has to be some just slightly new iteration of the old properties: some new show, new app, new drug, new device. […] What is interesting at the moment are the strategies being deployed to spread the cost and lower the risk of this routine innovation. This is what I think start-up culture is all about. It spreads and privatizes the risk while providing privileged access to innovation that is starting to prove its value to the vectoral class, whose ‘business model’ is to own […] new kinds of intellectual property.11Any utopian idealism around a radical social mobility brought about by internet entrepreneurial freedoms is certainly hampered by the world in which Wark describes; where a new oligarchy gains a tighter grip on today’s means of production (read: the Googles of the world) while extracting value from uses of ‘hacker class’ intellectual property. Yung Lean in this sense is an interesting musician: not radically innovative, but routinely innovative, he is the user of an online platform that has played the game well. Sven Lütticken suggests that with ‘new labour’ we live in a contemporary culture of performance. He notes that what marks this new labour is an ‘inability to distinguish’ between labour and other formerly separate aspects of life (such as leisure and free time). Working for money on the basis of our ‘objective economical pressures’ becomes intertwined with the development and display (or performance) of ‘subjectivities that are constantly updated, upgraded, remodelled’.12 Yung Lean’s stylised and emotive rap is evidently a public performance (labour) of his subjective fandom (leisure). To appropriate a term from French artist collective Claire Fontaine, Yung Lean is an uncritical ‘ready-made artist’. He is an inevitable product of the logic facilitated by digital network culture, of the user-as-producer. If the old Marxian suggestion still holds that the economic base of society will determine the art and music of our day, it’s now not surprising that the internet has made a rap star of a Swedish teenage consumer.

Jared Davis is a writer and curator from Melbourne.

1. Claire Fontaine, ‘Ready-Made Artist and Human Strike: A Few Clarifications’, 2005, www.clairefontaine.ws/pdf/readymade_eng.pdf, accessed 4 February 2015.

2. ‘Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal’, 2013, Quote Investigator, quoteinvestigator.com/2013/03/06/artists-steal, accessed 4 February 2015.

3. Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, ‘Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?’ The Art Newspaper, no. 262, 2014, www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Did-Marcel-Duchamp-steal-Elsas-urinal/36155, accessed 4 February 2015.

4. Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Routledge, London, 1979, reprint 1997, p. 2.

5. Sarah Thornton shares such a reading of subcultures, see: Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1996.

6. Claire Bishop, ‘Digital Divide: Claire Bishop on Contemporary Art and New Media’, Artforum International, vol. 51, no. 1, 2012, p. 437.

7. Such discussions are necessary and have been occurring of late; think of the debates around another internet rapper of sorts, Iggy Azalea. See: Jeff Chang, ‘Azealia Banks, Iggy Azalea and hip-hop’s appropriation problem’, 2014, The Guardian www.theguardian.com/music/2014/dec/24/iggy-azalea-azealia-banks-hip-hop-appropriation-problem, accessed 6 February 2015.

8. Martin Roberts, ‘Notes on the Global Underground: Subcultures and Globalization’, in Ken Gelder (ed.) The Subcultures Reader, Routledge, Oxon, 2005, p. 582.

9. David Joselit, After Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2013.

10. David Harvey, ‘Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 610, March, 2007, p. 22.

11. McKenzie Wark, ‘Digital Labor and the Anthropocene’, DIS Magazine, 2014, dismagazine.com/disillusioned/discussion-disillusioned/70983/mckenzie-wark-digital-labor-and-the-anthropocene, accessed 4 February 2015.

[^12]: Sven Lütticken, ‘Autonomy after the Fact’, Open, no. 23, 2012, p. 100.