I saw the exhibition Allegory of the Cave Painting at Extra City in Antwerp in November 2014. I was en route to Amsterdam, where I was moving into a new apartment that very evening. While watching one of the films in the exhibition, Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan’s Route Sedentaire (2001), I encountered something odd. The building depicted on the screen looked a lot like the building in Amsterdam that I was about to move into. I wasn’t certain, I had only been there once before—but, while I watched, the image of my three-week-old memory and the thirteen-year-old image on the screen seemed to be(come) one. In the film, the Dutch artist Lonnie van Brummelen is shown dragging a plaster cast of a classical statue of Hermes from her home in Amsterdam to the site of the Lascaux caves in the south of France, on foot. The journey took three months; the film of it takes four-and-a-half hours. The heavy plaster body of the winged god-messenger degrades along the way, leaving a short-lived chalky white trail on the ground behind. The remains of the once life-size figure, now just a head and some broken torso, were displayed on the ground at Extra City, amongst other fragmented documents from the journey. When I left Antwerp for Amsterdam, I thought about this journey south with Hermes, and I wondered if my journey north was covering any of the same ground, in reverse. Then, when I got to my destination I saw the names ‘Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan’ on the intercom at the front of the building, confirming that I had indeed arrived at the departure point that is shown in the film.

Coincidences are folds, where causally disconnected places/times suddenly touch and concur (the word comes from the Latin concurrere for ‘run together, assemble hurriedly’). This particular coincidence had special resonance because the work my new neighbours had made here, all those years before, seemed to be concerned precisely with questions of origins and departures, of returning and being left behind. Hermes, bearer of messages, god of travel and trade, patron of merchants and thieves too—he moves between disconnected places and times, rarely taking the most efficient route. Route Sedentaire was shot on 16mm film, and, as part of the conception of the work, there are no copies. This means that each screening of the film irreversibly alters it; to look at these images is to contaminate them. And in the deteriorating copy-less film, a deteriorating copy of an ancient statue is delivered to Lascaux, which is a site that exists for us only as a copy of itself. The cave was sealed off half a century ago, when an invading fungus was found to be degrading the prehistoric pictures, and a concrete facsimile was made nearby. So, in the film, Hermes—or what was left of the cast of the carved image of him—delivered van Brummelen and de Haan’s message to Lascaux II, where copies of the seventeen-thousand-year-old images were executed in the 1970s and 1980s, as proxies for the now-inaccessible originals.

The work relates to many of the broader themes that are at play in Allegory of the Cave Painting—such as antiquity, prehistory and their ongoing reconstitution; or preservation, reproduction and their impossibilities. The exhibition is a response to a remarkable discovery that was made in 2010, concerning the Gwion Gwion rock paintings in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Some researchers, led by neuroscientist Jack Pettigrew, were attempting to date these surprisingly well-preserved Paleolithic pictures, which had previously eluded carbon dating and other scientific methods for determining the age of things. They found that the reason the images had survived with such vibrancy was that colonies of living pigmented microorganisms had taken over, and the painted surfaces were in fact ‘biofilms’ of blackish fungi and reddish bacteria, which were enacting perpetual self-renewal in situ. The researchers speculated that the original paint could have had spores within it, initiating a stable symbiotic relationship where the fungi and bacteria live off each other through an exchange of water and carbohydrates, with successive generations growing by consuming their ancestors, and etching the pictures ever further into the rock. They show us incredibly enduring traces of life and imagination from tens of thousands of years ago, but they are also live occurrences, temporally folded pictures that are giving birth to themselves. As I settled into my new home in Amsterdam, I sent some emails back down to Antwerp, with some questions for the exhibition curator and Extra City artistic director Mihnea Mircan.

AG

I was looking at bread recipes online recently and I found this statement: ‘Yeast microbes are amongst the earliest domesticated organisms.’ I tried to think of the world from the perspective of this unicellular fungus that is put to work raising bread dough. Many artworks in your exhibition feature creative/destructive input from non-humans; the moving images in Gustav Metzger’s work are performed live by heat-sensitive liquid crystals, for instance, or there’s Ilana Halperin’s petrified mineral sculptures made in/by the limestone caves of Fontaines Pétrifiantes de Saint-Nectaire. Can you comment on the participation of non-human organisms, forces and processes throughout the exhibition?

MM

The exhibition juxtaposed these instances when non-human actants seem emancipated from artistic control and perform the image, with cases, less adventurous perhaps, where intention is very much in the hands of the artist. To respond directly to your two examples, Metzger’s liquid crystals, and the uncontrolled, psychedelic exuberance of their heat-generated permutations, was counterbalanced by his Drop on a Hot Plate, where endless change—the evaporation and replenishment of that droplet of water—is stilled into something that I would describe as a ‘spatial photograph’. Halperin’s mineralogical vertebrae, encrusted with limestone in a gesture that adds stone to wood to the same extent that it removes stone from cave, stone with which the cave would fill itself up, was paired with a work as delicately poised between addition and subtraction. Miklos Onucsan’s inscriptions—his Unfinished Measurements—into pebbles, of what had been the pebble’s weight prior to the inscription, is maybe the (geo)logical, arithmetic equivalent of a headstone. Susanne Kriemann’s self-portraits of radioactive materials, imprinting themselves on photosensitive paper in ways that are non-mimetic, that do not engender a ‘portrait’ of actual shapes but an a-visual interlocking of toxic auras, has an oblique relation to the Fabio Mauri performance Intellectual, with/on Pier Paolo Pasolini, where the film The Gospel according to St. Matthew is projected onto the director’s own chest.

If these juxtapositions worked, I hope they did two things. Crucially, I hope they re-formulated the auctorial suspension, between human and bacterial agency, of the Gwion Gwion paintings, which were the mental model for the show, where a painted surface, demarcated forty thousand years ago, is constantly rejuvenated and reproduced, in both senses of the word, by a biofilm of bacteria and fungi. As an aside, and possibly more to the point that you raise, they did not gesture towards a post-humanist paradigm, or did not try and connect a moment ‘before the human’ to a ‘world without us’. I was more interested in creating an indistinction between the conventional material, gestures and tropes of art-making, with the Gwion Gwion as instigation. An indistinction that may have accompanied what the poet Clayton Eshleman calls ‘the first nights and days of soul-making’.

In the research towards the exhibition I came across extraordinary instances of ‘contamination’, situations where, like in the Gwion Gwion, bacteria are employed to produce purity and integrity, rather than signal decrepitude. I also had a look at what is conventionally known as BioArt, but found that its rhetoric of delegation, of relinquished authorship and faux-naturalness, recalls some of the ideological ambiguities of ‘identity art’ of the 1990s, with micro- or macro-organisms in the place of the migrants or the underprivileged. There seems to be a strange collusion between the melancholic discourse of the Anthropocene and the way in which such experiments articulate an Anthropo-scene.

AG

The theme of this issue of un is subject(s/ivity/hood/ion). Does your exhibition have a subject? There seem to be a number of running themes, running over and into each other. I’m particularly interested in the temporal confusions and complexities, which you have already alluded to. The rising–falling (non)motion in Metzger’s evaporating drop pictures simultaneous stasis and dynamism, where something that looks delineated and suspended can in fact be an unfurling process. There is also the very-old-very-new nature of the Gwion Gwion; they are amongst the most ancient of pictures, and yet by virtue of their living components they are always new, and always being re-newed. The remarkable endurance of the pictures is paradoxically in and of change; their continuity relies on discontinuity. Can you speak more about the tensions and interrelations between stillness and motion, ‘long ago’ and ‘right now’, conservation and transformation, etc., throughout the exhibition? What are the potential implications of this on the time of art historical inquiry, and that of ‘contemporary’ art?

MM

To respond directly to the theme of the issue, I would venture that the exhibition attempted to think, along archaeology at large, about the moment when there is a subject, about the inaugural flash or cataclysmic rupture whereby subjecthood is wrested from subjectless matter: about the noetic thrust that begins to carve its way and its recognisable shapes into what had been myopic space, about the unnerving tipping point between the disincarnating faculties of thought and the incarnating powers of matter. The remarkable South African archaeologist David Lewis Williams calls this the emergence of the ‘mind in cave’, immediately echoed in the excavation of a cave into the mind. With each ‘new’ archaeological find (the paradoxical novelty of the very old, of the impossibly old), our modernity is posed the progressively larger, older and more intricate question of its own sources, of the cause and effect that led to the first cause and effect, of the first things before the first things—the chronological converse of a messianic destiny, of a climactic moment and of an exit from history, where we would inspect, congratulate ourselves for or be crushed by the last things after the last things. The compulsion of the inaugural moment is still there, in archaeology, in the museum, in mental reflexes: a crossing into the human, a turning away from what the human is not.

But perhaps a ‘subject’ more clearly delineated in the show is the space of interlocution between two quasi-subjects, two quasi-identities, each dependent on the other for its constitution and autonomy. Modernity ventriloquises its ancestors, rescues them from their own aimlessness or languor and teaches them to feel, think and speak, has them toil at the edges of identity: by resolving their incapacities, it itself can begin. Our present rehearses its phrases, dreams and provisional conclusions, in the past: a prologue, so that we can begin to be who we are. This is one of the senses in which the mechanism of allegory—prehistory as an essentially allegorical site of enunciation, since it cannot be ‘itself’—is not in possession of any of the instruments, granted retrospectively and parsimoniously, that would allow it to claim the condition and jurisdiction of a subject.

With the Gwion Gwion, this scenario is perturbed. The ‘message’ of the paintings is encrypted by chronological distance and by bacterial activity, what they might mean cannot be disentangled from what they are, as it is impossible to separate painting from sculpture, art from life, figure from frame, original from copy, a lost technology from pure environmental contingency—and these collapsed distinctions suggest again an allegorical inversion. The ‘message’ manifests itself as an automorphism, both stubborn and delicate, by which the identity, or subject, of those paintings keeps becoming itself, reproducing into its exact replica.

Finally, in different ways, these trajectories of interrogation structured the exhibition and worked as its subjects: not to be resolved, but to be thought with. The primordial scene or the advent of the visible, art and life, or contamination interwove throughout the exhibition. It might be interesting to insist on the question of lost technologies, of striking intersections of what is normally relegated to the status of ‘primitive’ ritual and the discoveries allowed by ever-larger telescopes or ever-more-accurate microscopes of contemporary science. As I think you know, the traditional owners of the region, in the Kimberley, across which the Gwion Gwion are spread, speak of a bird, the kujon, who attends permanently to the paintings (and thus explain why the Gwion Gwion are never repainted). The kujon repaints the images with its blood, using its beak or the tip of a feather. The bacterial replenishment hypothesis—allowed, for the team lead by Jack Pettigrew, by quite advanced scientific instruments and protocols—intersects a fragment of Aboriginal lore in describing precisely the same reality, the circulation of a blood in the veins of those painting, their longevity and chromatic vividness.

AG

This story of the bird’s continuing reconstitution of the pictures has itself been continually reconstituted, within pan-generational oral traditions that keep ancestral voices present. The coincidence of the ancient story’s premise with the findings of high technology is striking, but this isn’t an isolated case of situated, ancestral, indigenous knowledge anticipating the ‘discoveries’ of Western science. Your exhibition presents a number of other instances; for example, Susan Schuppli’s film Can the sun lie? tells us how claims made by Inuit elders that the sun in the Canadian Arctic had started setting further west along the horizon were initially met with vehement rejection by the scientific community, before methods that were in keeping with the epistemological framework of science arrived at the same conclusion… But, as far as I can tell, these accounts throughout the exhibition all come from non-indigenous voices. Did you not invite any Aboriginal artists to participate in the project? And, did you have any contact with the Kimberley communities for whom the sites of these paintings are highly sacred? As I’m sure you know, the situation in Australia is dire. To what extent do you think this exhibition in Antwerp should deal with the sociopolitical context of its ‘allegory’, which is also a real place?

MM

Before I attempt a response to your difficult question, I would like to qualify—or maybe introduce a delay in—the notion of ‘anticipation’, as it seems to indicate a linearity by which contemporary science was to arrive, inevitably, to the same findings, to catch up. With these unlikely intersections, it might be more productive to think that discrete worlds of vision come into aleatory contact, that they become, for a split second, reciprocally visible. That different modes of sense-making, desires and practices coincide, even if they originate in distinct alignments of ‘science’ and ‘ritual’. The ‘world’ that results from these juxtapositions unfolds at different speeds and according to different rules. Articulating this suggestion is as far as the exhibition goes, as you correctly suggest.

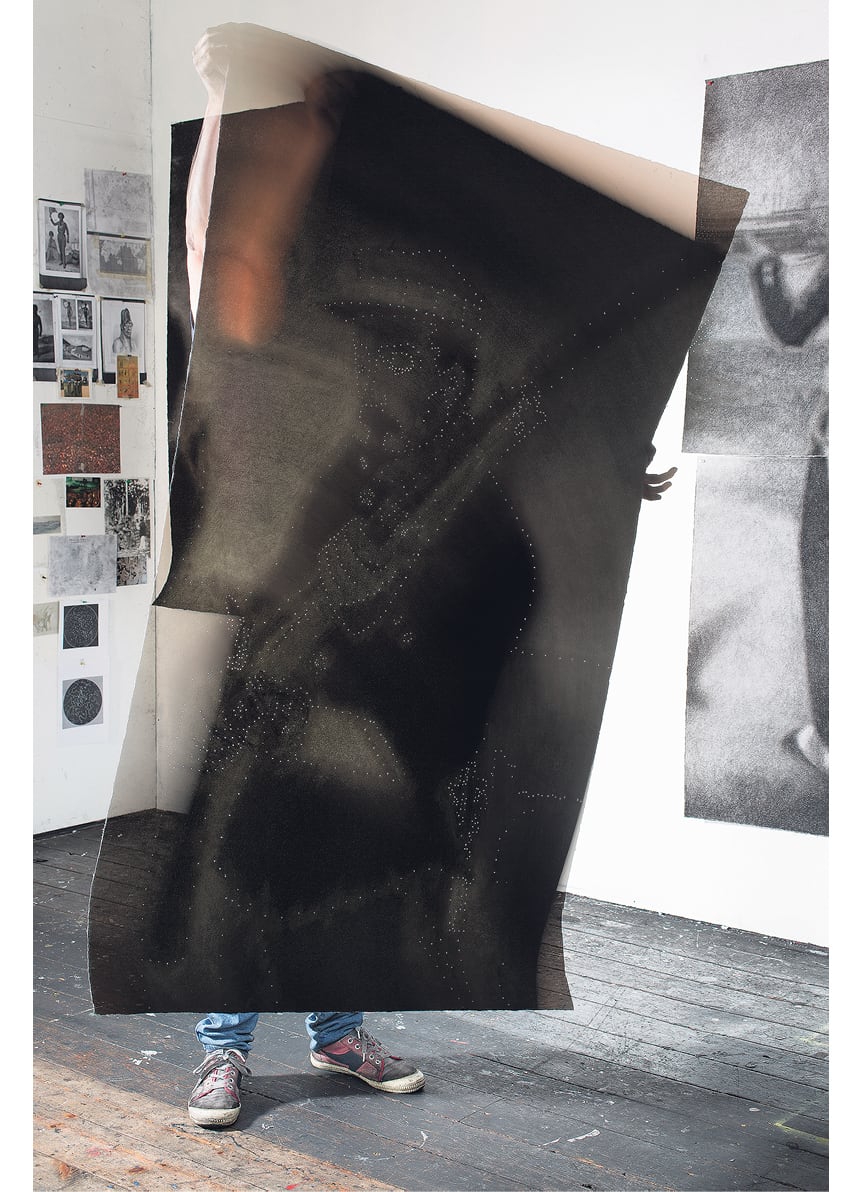

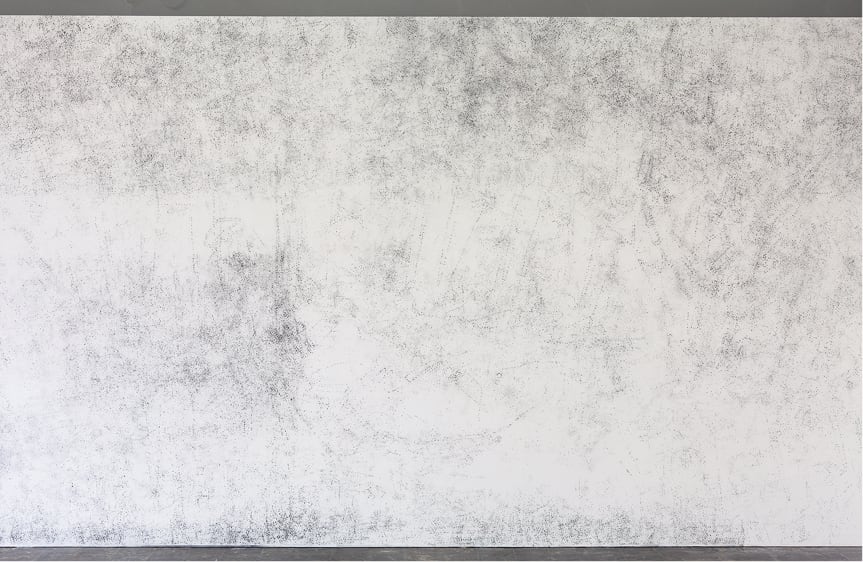

Further to the examples you mention, there’s that cave-like geological formation that the Dogon people use as astronomical observatory: taking a step back, as opposed to prosthetically extending vision with a powerful telescope. This move away from the object of observation, as opposed to reaching out to it—telescopically and metaphorically—allows them to see the star Sirius in a different way than science does. Jerome Blumberg’s documentary cannot quite resolve the puzzling fact that an ancient cosmology is organised around astronomical information that, on the other side of this boundary between paradigms, has only recently been retrieved by those optical giants installed in the Atacama Desert. I think the film allows these two halves of the same truth to coexist in a Zeno-like paradox. Blumberg’s work has been quite important in thinking about the exhibition, about how different ways of world-making and world-picturing could be anamorphically conjoined in a single object, that would thus lead different lives in those different systems, and exist as their incomplete superposition. I think Tom Nicholson’s de-structuring of the Joseph Selleny narrative, materially pounced and allegorically stretched up to the point where it begins to resemble a negative map of the world, produces a palimpsest of different speeds and worlds of vision. So does Jonas Staal’s comparative study of exuberantly modernist Brasília and Spiritist Nosso Lar—where we find ideological complicity between two Brazilian city models (one built and the other an ethereal station between different moments in the incarnation of souls) that should have nothing in common.

I had imagined the Antwerp leg of the project as a reflection on distance and intimacy, as a response to the wordless solicitation of the Gwion Gwion. There is violence, of course, in wresting the story of bacterial rejuvenation of those paintings from a very delicate ecology of gestures and beliefs, from a fraught history and from an often dispiriting archaeology in the Kimberley. I had imagined that a second episode, crucial in how this project could learn and grow, would be an Australian iteration, where the different conversations that these paintings have occasioned, bringing me into contact with remarkable practitioners, would be embodied in a far more context-sensitive response. I have to confess I know very little about the different layers of art practice—and the forms in which these embody political activism or advocacy—in Australia. Google is of little help charting these specificities, affording a look beyond the more visible—sometimes because they are more ostentatiously confrontational or ‘exotic’—positions. Another, mediocre, Zeno paradox is that it is only through making this first episode of the project, with all its limitations and failings, that I am encountering the interlocutors I can learn from, who can guide me to a more nuanced understanding of how bacterial and human colonies echo one another. Of how the replication of those painterly microorganisms could be posited as a nexus of historical, political and artistic narratives.