Cartoon meets calligraphy meets word game meets mind map. Such is the mode of Agatha Gothe-Snape’s

Free Speaking, which ran at Gertrude Contemporary’s Studio 12 from 17 October to 15 November 2014. Marked with an almost-anachronistic handwritten immediacy, the suite of drawings were made perfunctorily by the artist over a period of one week, in black permanent marker on delicate/durable butcher’s paper—calling to mind classroom egalitarianism, the space of the

no wrong question. The title of the exhibition resonates with the recent spate of rhetoric across global media regarding the freedom of speech, which locally has resulted in claims to a precarious ‘freedom’ wherein racism is at risk of being protected. The works are shown in the wake of Gothe-Snape’s

UNTITLED, an epic series of interchanging headlines inscribing found, overheard, readymade and decontextualised phrases into the promotion of the 2014 Berlin Biennale.

Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations—naturally. They have been out and about, on people’s lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries.

The

Free Speaking drawings invite a certain intimate looking that recalls the word games section of the newspaper, that avowedly daggy realm of recreational linguistics, where language flips out to revel in material stupidity; an operation antithetical to that of the authoritative, dogmatic front-page headline. I have loved recreational linguistics since childhood for its beautiful articulation (and defiance) of the entrapment of words in habitual convention. At the exhibition opening I overhear two women talking about Gothe-Snape’s presentation, one advises the other not to make the trip upstairs to Studio 12 because it’s just some silly drawings, ‘not much’, which is a perfectly useful statement.

A proper use of words is not to make a useful statement, for a useful statement can only mean one definite thing, and beside the surface meaning words contain so many sunken meanings.

In a drawing titled

WRONG SIDE ANGELA (2014), a diamond of letters peppered with mirror-imaging slowly unravels to form the circular statement

THE WRONG SIDE ANGELA STILL

or maybe

STILL THE WRONG SIDE ANGELA

depending on where you jump in. The allusion is to Angela Brennan’s 2004 text-painting

EVERY MORNING I WAKE UP ON THE WRONG SIDE OF CAPITALISM. The ambiguity is to whether Angela is still on ‘the wrong side’ of capitalism in 2015, aching with the ambivalence of such a statement, or whether she (and I) are simply on the wrong, habituated, and settled side of Agatha’s irreverently twisting pictorial universe. Here, visual riddles and play operate as tools for ideological critique, gesturing towards the potential of major reorganisation through interruptions on a micro scale.

When I write I know that I am drawing.

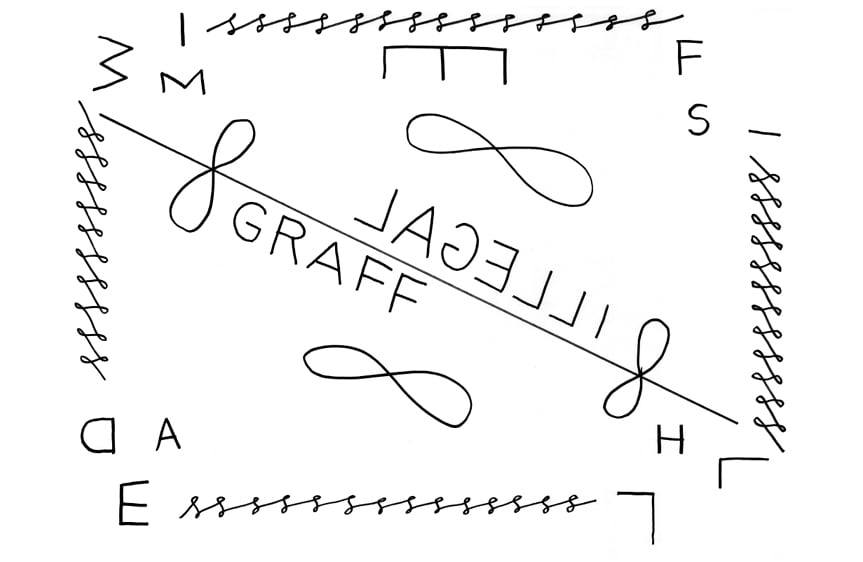

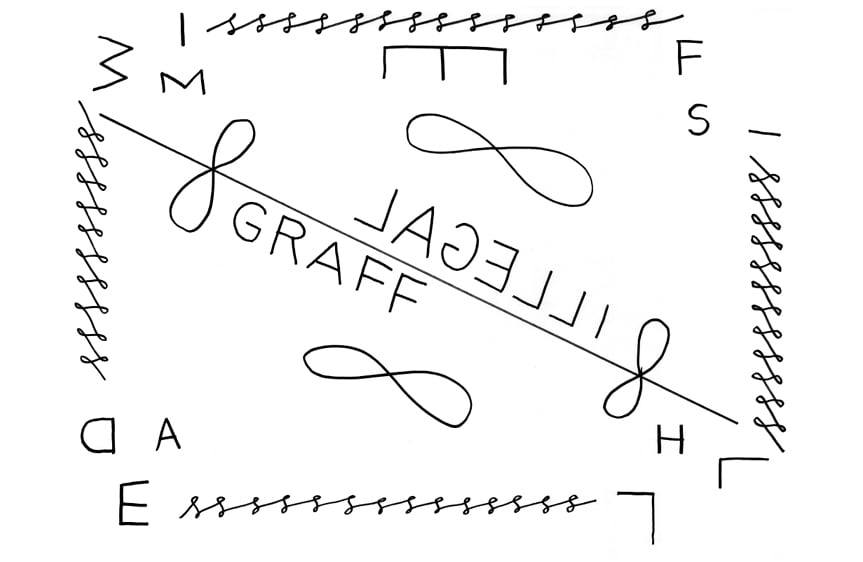

The titles of Gothe-Snape’s drawings are often incorporated pictorially, pirouetting with an air of nonchalance between handwritten linguistic meaning and the contrasting ‘muteness’ of gesture. Displacing the task of writing into the realm of drawing means presenting language as a mode that exists in parallel to or in service of the pictorial. Furthermore, writing as drawing prevents a document from being official through its bodily immediacy. This is pertinently suggested by one drawing in the show, which pictures the words

ILLEGAL GRAFF. Extra, surrounding letters float in a swarm of anagrammatic possibility:

l w a l f e d s e h m i i

could become

salified whelm aims fled while

wildish female

helms a wildlife

The gesture of handwriting takes place in opposition to the fixed impersonality, resolve and disembodied violence of the formal document. Graffiti is a personal inscription, a vernacular mode of re-authoring property. In Gothe-Snape’s drawings, handwritten ‘graffiti’ meets calligraphy in a marriage of loops, strokes and elegant delineations. Calligraphy, the painfully beautiful handwritten, was originally developed in the service of automatism: the channelling of God into divine scripture through the eradication of personal inflection. In place of a deity, the artist channels the words of anonymous authors into the realm of her drawings, a re-authoring that questions authority.

Authority lies in how someone speaks to you and the responsibilities underpinning this transaction. Authority lies in the way an artwork may address you. Authority lies in the right for speaking to take up space and receive attention.

There is this rhetoric everyone buys into about things needing to come out.

While

Free Speaking implicates a freedom of speech in the libertarian sense of the term, it also suggests the admirable quality of being frank. Frankness is a kind of speaking that privileges gut response and doesn’t negate but

delays responsibility for claims and utterances. This form of speaking—impulsive, associative, direct, passionate, confident in its unthinking—is tethered at one corner to the furnishings of psychoanalysis, as suggested in Gothe-Snape’s wry drawing of a chaise longue (

CHEZ LOUNGE, 2014). In this setting, our hidden desires reveal themselves in patterns decorating what we assert through speaking freely.

Yet free speaking is not always a precursor to therapeutic progress. It can be risky. It demands the audacity to speak

your mind in spite of risk—the danger of damaging feelings, popularity, reputation, of ushering scandal. It gestures to the importance of

keeping words in context, the potential violence of their displacement, and the responsibility that comes with such a task.

Poetic language is the occupation of the space of communication by words which escape the order of exchangeability.

Moving through Gothe-Snape’s drawings, any one detail feels as important as the next. A drawing of an

ELECTRONIC MONEY TRANSFER invites the question: in a world where nothing is free, what is the exchange value of free speech?

Proposing an answer to this question in astoundingly actual terms, a tweet I recently saw claimed that:

guarding Julian #Assange has cost British taxpayers almost £10mn. The besieged Ecuadorian embassy has been surrounded by police 24/7 for over two years. A Sharpie and butcher’s paper cost less than $10. Transcending monetary measure (price-logic), Gothe-Snape’s drawings entail a very slow form of looking and reading, and, in turn, a slow way of speaking to a viewer, which ultimately might not yield

much. This directly opposes the rapid economy of the headline in the era of clickbait journalism, wherein content is largely determined by its capacity to pique interest (read: revenue) instantaneously. As a whole

body of work, the drawings diffuse the location of a central spoken claim. While brainstorming and mind mapping are gestural means to a practical solution, Gothe-Snape’s use of Sharpie on butcher’s paper reeks with the allure of posturing a permanent draft, bathed in oxymoronic glory. Rather than imparting facts, as in the media, the show leaves you to experience the pleasant dizziness of contradictions.

Lauren Burrow is an artist currently living in Melbourne.

[^6]: Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi,

The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, Semiotext(e), Los Angeles, 2012, p. 22.