The relationship between society and image-production was explored in The Form That Accommodates The Mess, a program of four films curated by OtherFilm in collaboration with the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Included were Robin Laurie and Margot Nash’s We Aim to Please (1976), Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Dara Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978), and Duncan Campbell’s Bernadette (2008). The selection reflected a concern with the expression and construction of gender identity; ‘messy’ both in the sense of Kristeva’s alignment of the female sex with abjection, and the assortment of genres, styles and conventions across the four films.

Within contemporary culture images are not in stasis or confined to contexts, technologies or eras, but rather exist in a realm of constant renewal and reinvention. In her article ‘Too Much World: Is The Internet Dead?’, Hito Steyerl notes, ‘images are not objective or subjective renditions of a pre-existing condition…they are rather nodes of energy and matter that migrate across different supports, shaping and affecting people, landscapes, politics and social systems’.1 Reflecting the blind spots of second-wave feminism, The Form That Accommodates The Mess failed to move beyond a white, hetero-normative context. In the program’s focus on films primarily created in the 1970s was nostalgia for a mythologised, romanticised image of feminism in that era—a feminism whose goals appeared unanimous, and whose framework of resistance seemed clear. However the program simultaneously deconstructed this ideal. The final film screened, Bernadette by Irish artist Duncan Campbell, was made in 2008. As the only film in the program not produced in the 1970s, it is also the only work with hindsight. Bernadette draws viewers into a tumultuous Joan Of Arc tale, before unravelling to reveal the reductive nature of the mediated, romanticised narrative, triggering a revaluation of the program. Embedded in The Form That Accommodates The Mess was a layered analysis of not only how images are produced and manipulated, but how historical events and artistic movements are condensed within cultural memory.

We Aim to Please, 1976, by Laurie and Nash is a pastiche of political statements, quotations, monologues and improvised performances starring the artists themselves. The film opens with shots of the women as they speak into the camera, smearing makeup across their faces like war paint. In another scene, a tomato is thrown at the lens, shattering the unity of the image and reminding the audience of its contrivance. By using fresh produce to evoke corporeal experience, the filmmakers demonstrate how violence and carnality can be discussed without reveling in the abjection of bodily fluids. By using their own bodies—naked, clothed or painted in lipstick—Laurie and Nash reclaim their visibility and autonomy as female subjects. To view this film in a contemporary context, we could easily consider the self-documentary and cultural pastiche, as a pre-curser to social media selfing. While social media and technologies of self-documentation might be easily accessible today, the film still remains a compelling antithesis to the representations of women within mainstream film of the era. Similar deconstructive self-portraiture has been produced in more recent decades by African-American artist Renee Cox. Subverting mainstream expectation regarding not only sex but race, Cox reimagines the narratives of a white-washed, patriarchal culture by inserting herself into iconic scenes, such as the last supper in Yo Mamma’s Last Supper (1996), or restaging Ingres Grande Odalisque (1814) in Black Baby (2001).

Laurie introduced the film program in person, giving a short speech in which she described her and Nash’s beginnings, from handing out zines printed in their living room in Melbourne to their involvement in the anarchist community. Perhaps most significant was Laurie’s concluding note in which she suggested that the radical progressivism of the 1970s needs to be rekindled in order to break down new, more ambiguous gender-barriers.2 In the contemporary climate, we are no longer able to concisely articulate gender issues and inequalities along the same battle lines. In a ‘meta-modern’ world, in which we are all (as contemporary subjects) authors, artists and creators—directors of our own cyber-narratives—issues of female subjectivity and its articulation exist within a web of postfeminist ideologies. While self-documentation might be common in contemporary contexts, the agency of self-representation appears less effective today as tool of political commentary. Self-representation itself has been subsumed by a cultural vocabulary that encourages us to conform. Spain and UK-based artist Amalia Ulman explored this in an Instagram profile comprised of factual and fictional accounts of her life. In an array of selfies and self-shot videos depicting herself posing, pouting or twerking, Ulman interacts with the virtual world through a predetermined language, enacting the life of an LA ‘glamazon’ while dishing out details of parties, breakups, plastic surgeries, and interviews with famous feminists; events we cannot know to be real or fictive and that echo the commodity and status-driven, hyper-aestheticised nature of ego-based social media. Moreover, Ulman’s self-representation raises complicated questions in the wake of third-wave feminism regarding what it is to represent ourselves as gendered within these frameworks, and whether these representations are compromising or empowering (or both or neither). Danish-Filipino artist Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen similarly explores culturally gendered stereotypes, though less ambiguously, in music videos such as Absolute Exotic (2005) which use the semiotics of hip-hop and pop-cultural exoticisation to deconstruct reductive mainstream representations of mixed-race women. These explorations of mediated identity through digital media and moving image map the complex conditions of contemporary feminisms and the multiplexed issues of gender, sexuality and race that are absent in The Form That Accommodates The Mess.

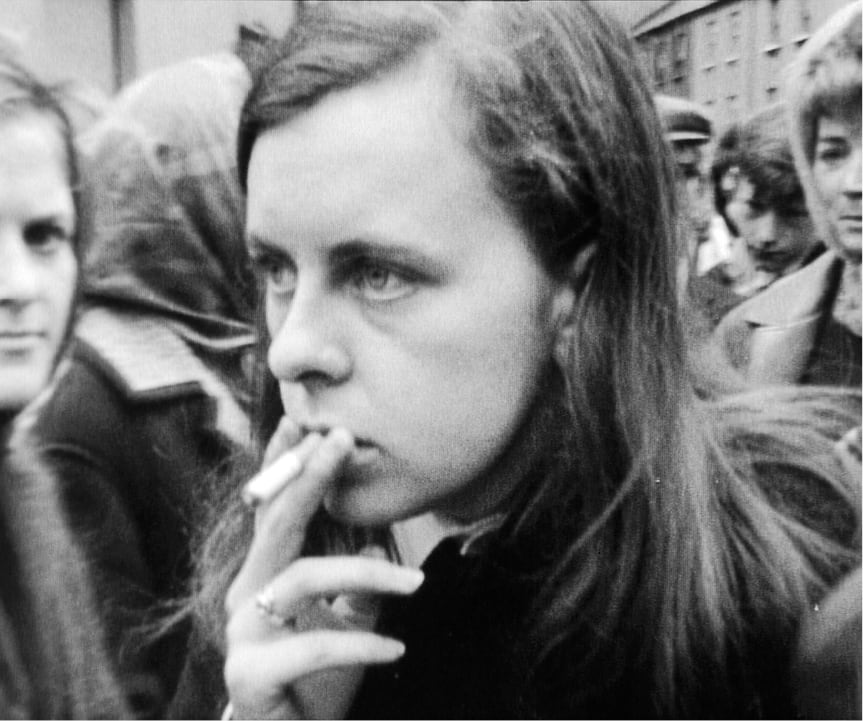

In the final film Bernadette 2008, Irish artist Duncan Campbell, recipient of the 2014 Turner Prize, collates footage of Irish republican political activist Bernadette Devlin who served as a member of the UK Parliament in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Focusing on her time in parliament and subsequent imprisonment for incitement to riot, Campbell creates a visual portrait of the young woman’s treacherous and provocative political career. While the film resembles a historical documentary, it eludes any concise claim to truth, instead deflecting to the representation of Devlin put forth in the media footage Campbell has appropriated, edited and merged with his own fictions. In this film, the only work in the program not by a woman, Campbell resists compiling the history of Devlin (which would be misguided) but instead shows a history of cultural perception as captured in the archives. While the first three films inadvertently evoke nostalgia, this film addresses an archetype of female empowerment that embodies our cultural memory of 1970s activism, revealing it as a reductive mythologisation of a far more complicated, problematic and robust period in history that cannot be condensed or truly knowable.

Tara Heffernan is PhD candidate in Art History/Cultural Studies at The University of Queensland.