As in previous work by Nikos Pantazopolous, the installation of photographs in Wearing negotiates the symbolic and semiotic connections between public and private sexuality. The permeability of erotic experience within and around architecture is explored through a language of ‘place’ as defined by usage, coded and clandestine, modern and historical. Where projects such as OMIA 399BC– (2012) traced the history of the homosexual as outcast through a re-imagining of a men’s toilet block removed from Melbourne’s Treasury Gardens, and Dark Rooms (2013), a photographic suite documenting hidden sites of hedonistic activity, worked towards deconstructing the material and historical implications of sexuality as it responds to societal frameworks; Wearing offers the first-person subject as ‘lyric’, performed for, and within, a space which is not only public, but for which the act of exhibition is fundamental. Ambivalence toward exposition and concealment, however, is crucial to these works, as a representational theme, and as a spatial concept.

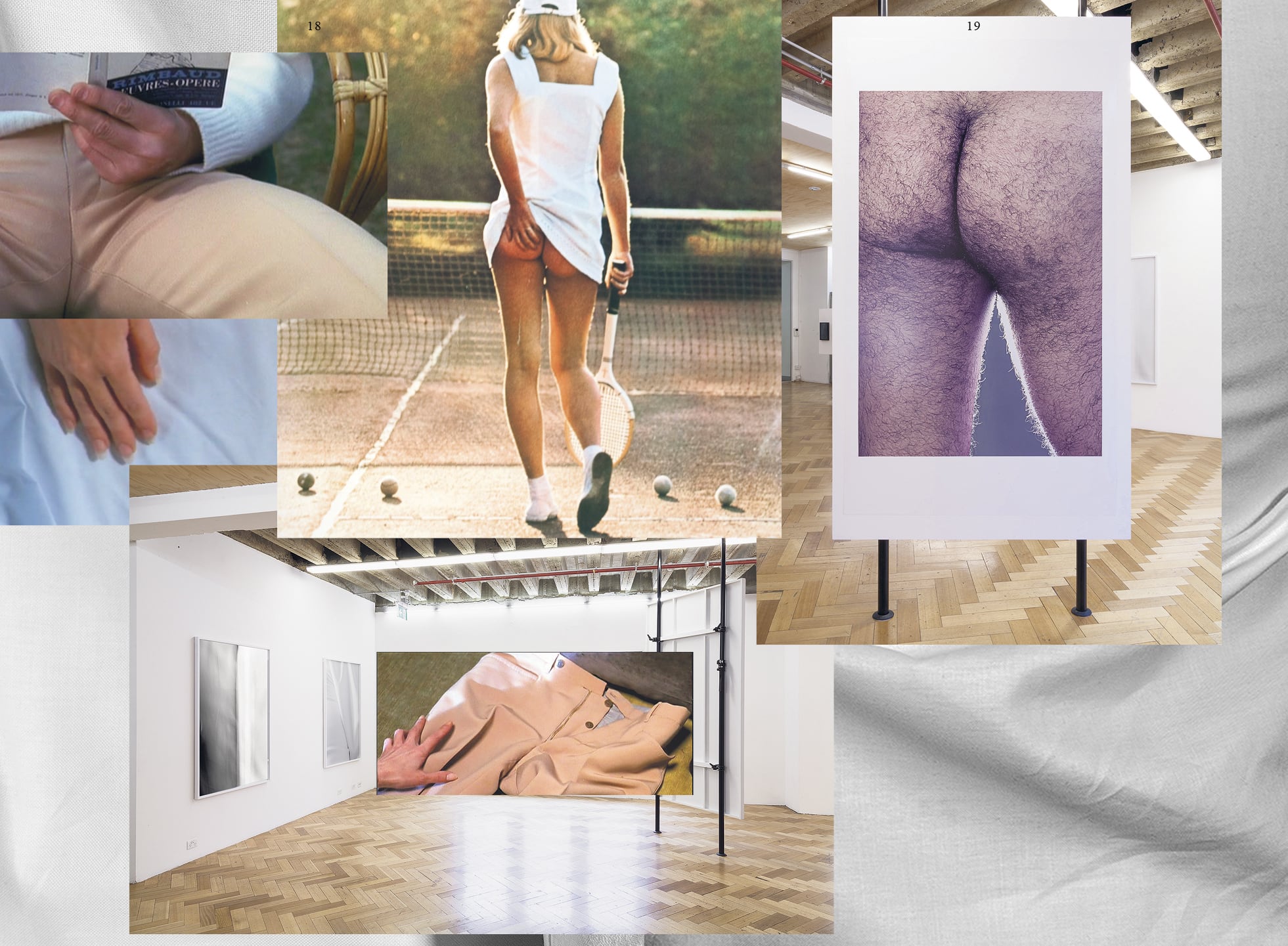

On entering the gallery’s foyer space the viewer immediately circulates inside Pantazopolous’ ‘forum’; a sequence of free-standing panels functioning as temporary walls, enacting a refusal of the existing exhibition space and giving armature to a series of photographic images, most of which present details of the artist’s clothed body. This system of poles and clamps recalls the aesthetic of a building site or photographer’s studio, and serves to delineate the exhibition space, but also establishes a ‘set’, both in the sense of representing an array of distinct and operative units, and as a scenographic space. This pseudo-amphitheatre, constructed from columns and facades, is an extrapolation of Pantazopolous’ particular form of ‘parchment and pediment’ classicism, which pivots between the pictorial and architectural. In this instance, the spatial arrangement forms an arena in which to witness the residue of the artist’s ‘performance’—closely cropped studies of a white shirt sheathed over the artist’s torso and limbs, a section of leather jacket, hinting at a particular gesture. Through their detail and scale, these images express, and compress, an optic of desire onto a micro-surface, articulating the body’s gesture in architectural and photographic space.

Lacking a defined identity, the body in these images finds a voice, a system of speech, through its interaction with clothing. This affect of intimacy, and the indulgent, sensuous eye Pantazopolous’ camera casts over these garments activates their status as fetish; their documentation in photographic form, however, framed and behind glass, denies the possibility of tactile experience. As a material site of visualised erotic charge, these clothes are simultaneously animated by the body they conceal, and projected upon by the engaged viewer, mediating the desire of both; like a photographic surface or cinema screen, the fabric is both container and projector. Rather than a veil that hides the wearer’s essence, the two are linked through a dialectical movement. The fetish, usually defined as a symbol substituted for the absent object, is described here through an action, locating its drive through an interactive response to the body, and through its relationship to what exists outside the frame. In these images, and critically, in their installation, the subject, object and fetish are equal and simultaneous participants, each complicit in activating the residual desire within this layering of ‘screens’.

The ‘fetish fabric’ maintains a dual agency, moving between the articulation of the body and the negation of its filth—what lies behind is both denied and released—and this fluid interchangeability of signs resides in the weave of Pantazopolous’ shirt. Through light and fibre, the performance is arrested, and an imprint is captured of the fetish object in the process of becoming an eroticised contact relic, reminiscent of the clothing abandoned by Terence Stamp’s ‘mysterious visitor’ in Pasolini’s Teorema (1968). Seen through Lucia’s (Silvana Mangano) gaze, the visitor’s garments assume an auratic presence; though discarded, the trousers, shirt and briefs are soiled, inhabited by a sensory and material ‘memory’ of their owner, and the camera describes their forms with a sculptural sensibility. Pasolini—an inveterate ‘fetish formalist’—was himself an enthusiast of the crisply laundered white shirt, an efficient register of the director’s intellectual rigour, clerical humanism, and elegant masculinity. Shortly before his death, this white shirt, whilst being worn by Pasolini, served as a surface for the projection of his own film (Il Vangelo secondo Matteo) by Fabio Mauri, in a notorious performance work entitled Intellectuale (1975). Much as Pasolini becomes the screen in Mauri’s performance, Pantazopolous ‘becomes’ his own surface, inscribing an inherent lyricism through the fabric’s folds and variations of transparency.

As a protagonist in Wearing, clothing holds a position between studied concealment and statement dressing. Pantazopoluous is unequivocally ‘raunchy in Givenchy’, but the grammar of these images extends beyond the long-established co-opting of fetish imagery by couture culture, occupying a territory informed by the symbolic language of classical sculpture and the suggestive forms of gestural abstraction. Despite the variety of folds and creases, and the interplay of subtle and dramatic lighting over textile, these images employ an all-over composition and are without any immediate rupture or opening onto an alternative meaning; they are either all punctum or none at all. As studies in materiality, they recall the continuity between skin and drapery in Classical sculpture; the articulation of form through building and removing material, rather than clothing it. Pantazopolous’ method of engaging the contemporary as cloaked by Classicism is evidenced in the sequence of small identical shots of the artist’s elbow clad in Mapplethorpean leather; this repeated motif creates a rhythmic refrain, a ‘beat’ which offers a counterpoint to the tonal arabesques in white cotton. The stacking of folds in black leather, and the angle of the artist’s arm, suggest an approximation of the ‘diagonal of personal ecstasy,’1 offering clues to a hidden act.

Wearing, as a visual and spatial experience, has an end; as the viewer approaches the turn leading into the next gallery, a final temporary wall, reversed and showing its back, impedes their passage. Only on entering the next space and looking back can this image be seen. It’s the installation’s only colour image, and also the only image of the body unclothed—a portrait of the artists buttocks—backlit and monumental. Bathed in glorious, triumphant light, Pantazopolous’ gift appears cut from Classical narrative, yet it mocks the viewer, perhaps in solidarity with Bataille’s L’Anus Solaire, the ‘parody of parodies’, simultaneously orifice and projector, giver and destroyer of life. As a gesture of finality, ‘Hairy Arse’2 re-iterates the artist’s and viewer’s position as simultaneously inside and outside these images, in which the visible and the hidden are equally engaged.