Late last year I went up to Bendigo for the launch of Chunxiao Qu’s poetry book at the La Trobe Art Institute. My partner and I decided to stay overnight because we had heard about a huge population of bats that live in a park there and we also wanted to check out a few of the town’s second-hand bookstores.

For my PhD I am researching art forgery in the twentieth century here in so-called Australia and these regional bookstores can yield some absolute gems — often self-publications which record what may previously have been oral histories and knowledge. For example, some books contain stories about long-hidden paintings and artworks that had mysteriously vanished. That Saturday, after marvelling at the bats for ten minutes, we walked over to the closest bookstore.

Amongst about twenty books on Ned Kelly, I found a medium-sized paperback titled A History of the Lang Family written by an R N Lang. It appeared to be a 2006 proof copy of a self-published book. Perhaps the author had never even ordered a proper print run? This book struck me not for the title or author but for the following pages which are reproduced here in un Magazine 17.1 RESIST.

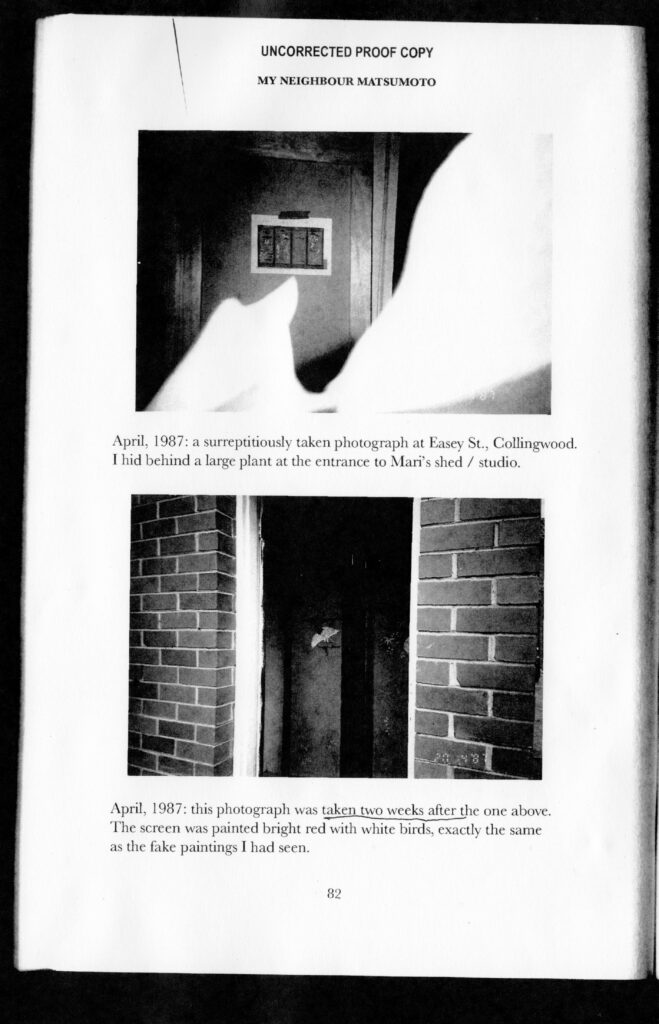

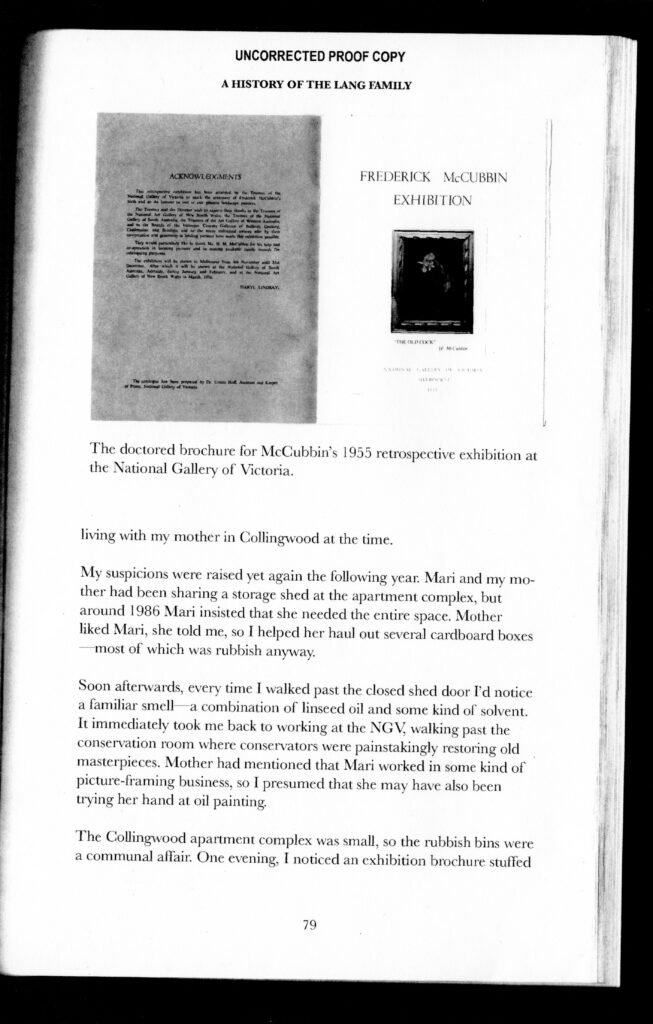

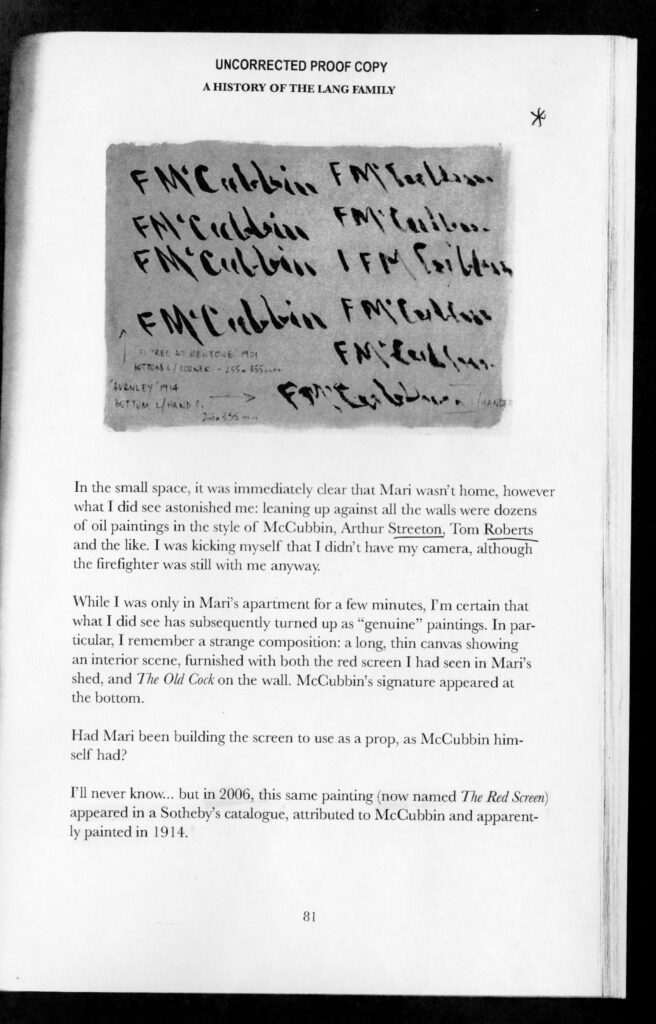

Lang mostly writes of her employment at the National Gallery of Victoria during the 1980s, however, in a chapter titled ‘My Neighbour Matsumoto,’ she recounts a story, accompanied by images, of what she believed to be an egregious case of art forgery. Lang claims that her neighbour, a Japanese woman named Mari Matsumoto, was forging oil paintings and passing them off as genuine works of the Australian Impressionists.

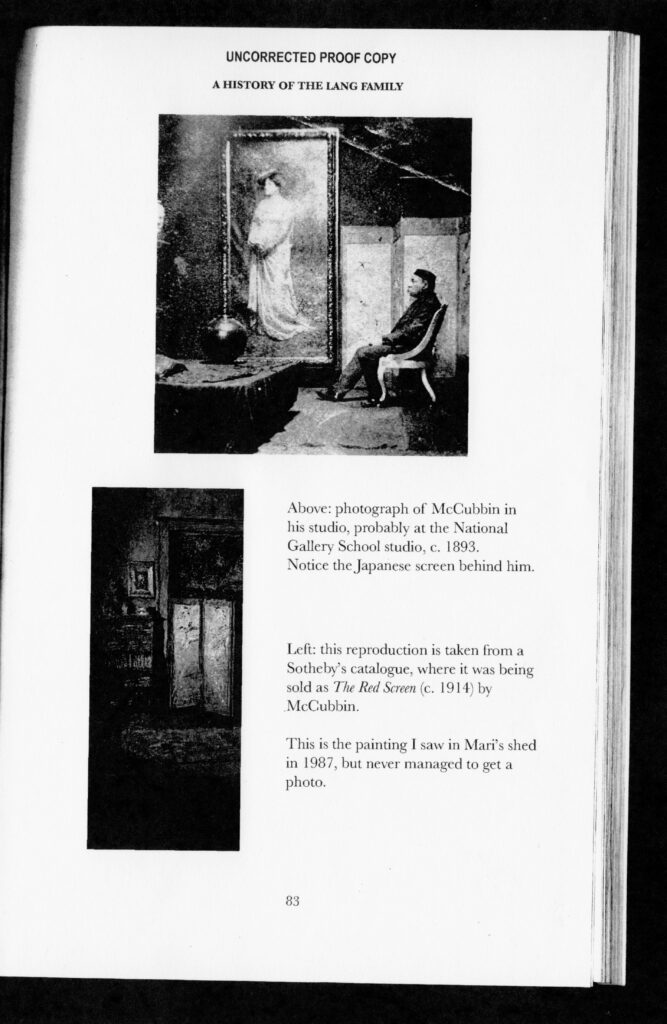

While compelling, I cannot account for the veracity of Lang’s claim except on one point. In 2011, a painting previously believed to be by Frederick McCubbin, The red screen (1914), was found to be a modern forgery and estimated to have been painted in the second half of the twentieth century. The red screen was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 2010 (the image no longer appears on their website). Lang claims in her book that she saw evidence of the forgery being produced by Matsumoto in 1987.

I will let Lang’s text speak for itself, however, if even a fraction of it is true, art historians and lovers of the Australian Impressionists will have to grapple with the following question: what if many of these icons of nationalism were fakes, painted by a Japanese woman in the late 1980s?