How can a culture move forward if it does not have access to its

past? For Jasmine Togo-Brisby, a fourth-generation Australian

South Sea Islander (ASSI) with ancestral lineage to the Vanuatu

islands of Ambae and Santo, artistic constructions of the past create routes and roots to imagine ASSI futurities. Togo-Brisby’s practice recuperates cultural memory to unveil the complex entwining of her family’s identity and the painful legacy of ‘blackbirding,’ the kidnapping and coercion of people into indentured labour. Over 62,000 Pacific people were tricked or coerced into indentured labour in Australia, with many not surviving the passage. Across Togo-Brisby’s practice, she has developed works that affirm the experiences and resilience of ‘Granny’ (the artist’s great-greatgrandmother), who was kidnapped in Vanuatu and taken to Sydney, where she was acquired as a house slave for the Wunderlich family in 1899. Recurring motifs such as sugar, sugar cane plantations and crows act as chronotopes that ground her works in the narratives of the Pacific slave trade and allow her to create uniquely South Sea Islander artworks.1 Two major new commissions, As Above So

Below, 2022 at Fremantle Art Centreand Open City (In Suspension), 2022 at Auckland Art Gallery extend her imagery of ships as symbols of resistance.

Both works can be read as ‘sister’ works that are premised

on the same vision, Togo-Brisby shares:

I hold an imagined image in my mind of my

granny, at 8 years old, after her

journey to Australia in the hold of a ship

looking up from below deck. Then, on

her first day at the Wunderlich’s house, she

lays down at night, looking up at

the decorative ceiling home.2

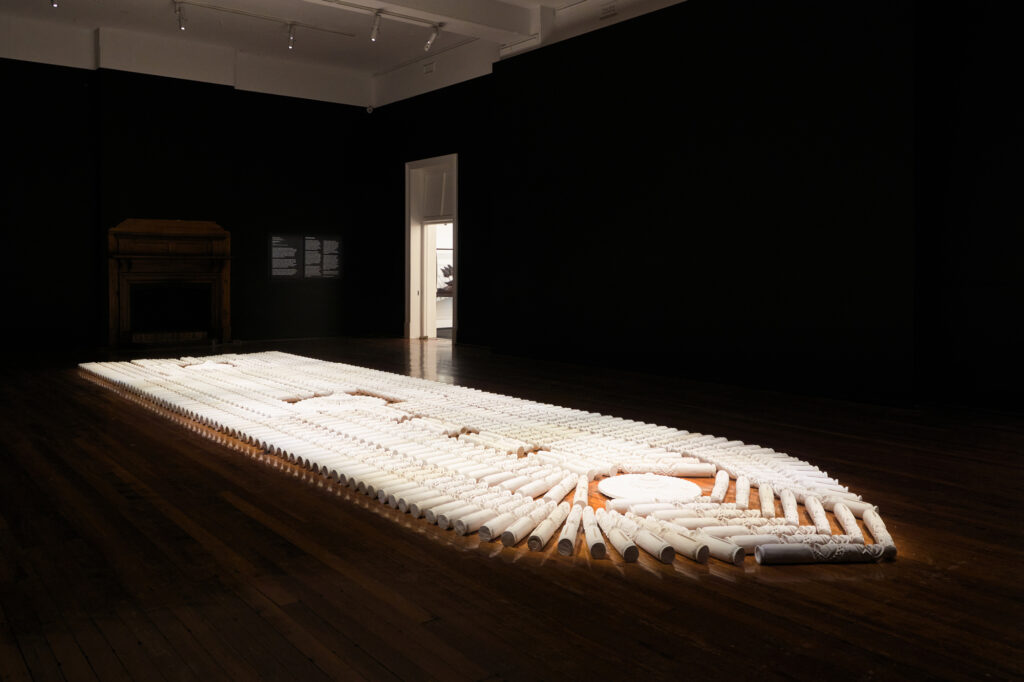

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, As above so below, 2022. Cast plaster.

9820mm x 2850 mm. Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned for Other Horizons by Fremantle Arts Centre in association with Perth Festival 2022-23, supported by Visual Arts Program Partner Wesfarmers Arts

As above so below, 2022. [detail] Cast plaster. Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned for Other Horizons by Fremantle Arts Centre in association with Perth Festival 2022-23, supported by Visual Arts Program Partner Wesfarmers Arts

Togo-Brisby’s vision of her Granny’s passage repossesses the

image of the slave ship as a site of resistance and cultural memory

in what art historian Cheryl Finley calls a ‘symbolic possession

of the past.’3 Both works draw on the enduring slave ship icon,

which traces back to the eighteenth-century British abolitionist

engraving Description of a Slave Ship, 1788 — a schematic

representation of the crowded lower deck of the slave ship’s

human cargo hold.4 The engraving exposed the underbelly of the

slave ship ‘Brookes,’ depicting the means of transporting enslaved

Africans to America. Alongside the schematic engraving is text

describing the inhumane dimensions of space for each individual

that only allowed for them to lie down; they could not fully sit up nor stand. Over 7000 of these engravings were printed as weapons to shock the public and to promote the abolition campaign to end the transatlantic slave trade.

The haunting schematic representation is recast in As Above So Below — an installation comprising 369 prone plaster tam tam (slit drum) sculptures arranged on the wooden floor of the Fremantle Art Centre’s main gallery. The sculptures were cast in white plaster from miniature souvenir tam tams from the artist’s collection. Customary tam tams are carved from wood and stand over three metres tall on the dancing ground of villages across Vanuatu. Togo-Brisby shares the Kastom of tam tams, saying, ‘the drums form a type of orchestra ceremonially used in communicating amongst the islands. When the lip of the drum

is struck it is said that the emerging sounds are the voices of our

ancestors.’5 In her installation, three variations of tam tam forms

are laid out following the schematic arrangement of bodies in the

abolitionist engraving that included men, women and children.

Though separated from Kastom and its original form, this configuration of tam tam sounds enduring messages of resistance

and the hope of the return home.

Taking our gaze from the floor to the ceiling, Open City (In Suspension) is a powerful architectural intervention where the form of the ship hovers ominously above us. Housed in a darkened room, the matte black ship is composed of ornate ceiling panels that evoke the decorative nineteenth-century pressed-tin ‘art-metal’ ceilings produced by Australian firm Wunderlich. In place of the typical floral and script-like motifs of Wunderlich ceilings, Togo-Brisby’s panels feature images of ships and sugarcane plants, and re-appropriates the image of a sugar refinery used in the branding of the Chelsea Sugar Company.6 Silhouettes of the artist, her mother Christine and daughter Eden holding miniature ships are repeated across the surface of this installation. They are seen across multiple bodies of work to reaffirm the endurance and survival of their matrilineal lineage. Taking Audre Lorde’s provocative admonishment that ‘themaster’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,’ these motifs surface the histories that lie dormant behind the decorative façade of Wunderlich ceilings.7 The visual entanglement of her panels echoes the entwined histories of Australian South Sea Islanders (ASSI) and the making of modernity in Australia.8

Togo-Brisby’s work sets out a vision of resistance and hope, which, as Karyn Recollet notes, does not reside ‘…so much in an unattainable dreamscape, but rather they are in constant figuration and reconfiguration all around us.’9 Each time chronotypes such as ships appear in Togo-Brisby’s work, they stand in for many other ASSI who are yet to find roots or voice. These ‘sister’ works draw on the schematic image of a ship, itself an image of resistance, to activate the stories of ASSI and to resist their erasure. In doing so, they recall images of resistance and hope already active in the world. Visions that can be found above and below, in the tracing of genealogy through archive and oral histories, and in looking backwards and forwards across the ocean.

Archive.’ Masters thesis. Massey University Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa, 2022, p. 11.

resilience’ in Hom Swit Hom. Artspace Mackay, Mackay. p. 12.

Master’s House, Penguin Classics, London, 2018, p 25.