We started HEAVY DUTY in the second half of 2020. The world was in a constant state of clash, but fortunately for us in Boorloo our geographic isolation allowed for a relative sense of ease. People previously living abroad were returning to the safety of the Boorloo dome, bringing with them stories of Covid-19 from the outside and inspiration from their exciting lives abroad. No one knew what was next, but from the safety of our bubble we were beginning to feel pretty smug about ourselves.

HEAVY DUTY started as an umbrella to house projects that ranged too broadly: sculpture, film, activism, stools, napkins, tape on the ground, whatever. We decided we wanted to make things together. It is easy to have ideas but harder to realise them. Collaborating meant we could do both. It meant we could make things with our hands, heads and friends. We wanted to do everything but be tied down to nothing. When we began working as a team, we were able to dismantle each other’s doubts, offer reassurance and gain perspective.

We are also extremely privileged. The way that we look and where we come from grants us the freedom to think and feel the way we do without restriction, responsibility or the expectation of others inhibiting us. We are also privileged in the way that we can choose to act anonymously. Thanks to this, we are able to do things more comfortably than others. To do things without fear of being fined, arrested or worse. HEAVY DUTY exercises this privilege, but, first, it must be acknowledged.

We took advantage of our privilege and anonymity to avoid unnecessary attention or influence from our personal and professional lives. I work in the public sector and live in constant fear of this cover being blown. The other half of HEAVY DUTY had a United States visa on the line. Anonymity hid our names from our bosses and allowed for our crew to expand and contract as needed. Without this anonymity we would have been far more restricted, or at least our perception of what we could do would have been different. The world had become one large screaming match and rathe than yell, we chose to take action quietly. With our names hidden we were able to erect street signs to direct travellers to sites of deforestation, poke fun at politicians through

‘illegally dumped’ sculptures and hang Hollywood-style signs

recognising traditional place names on tourist attractions on so

called Crown Land.1

HEAVY DUTY, The Boorloo Sign, 2021. All photos: Edward Avery

In anonymity we conceal our identities and with humour we deliver our ideas in a palatable and playful way. Playing to the myth of the Australian larrikin, we packaged our ideas as ‘taking the piss’ to speak to those that might not otherwise give these issues thought. These are the people that most probably need convincing, not you, reading this essay.

When we started, it felt like we were curious kids again in a blissfully ignorant period of endless fucking around. While cracks began to tear in what felt like the latest collapse of the world, we were working out how to fit sheets of MDF in a Honda Civic. As things worsened globally with Covid-19 infections rising, governmental neglect and increased police violence and abuse, we started seeing these issues exploding and amplified on social media. We saw virtue signalling, black squares, unsolicited expert advice and infographics. This is not a weighted criticism of the reactionary practice of social media activism but it is what motivated HEAVY DUTY’s shift of focus. We started to move away from the influences and inspiration that we had typically drawn on, such as, modern design, skateboarding and street

culture, turning our focus instead to what was going on in the world around us and bigger than us. Issues that focused on people

and space. We brought our focus finally to public space.

We start every project with the same premise, whether it is a bench welcoming and sheltering the homeless or truth telling plaques replacing those that celebrate colonial statues. Our work lives in the public sphere — a space that we believe is intended for all. Or at least the space that is said to be designated to be used by its namesake — the public. Until the public are told not to.

This is the irony of public space. While it is said that the fundamental role of public space is to accommodate for all citizens to engage with each other and their surrounding environment, the reality is often quite different. Public space is controlled by those in power who limit access and impose unfair rules and regulations. Public space is so often designed to serve the interests of those in power rather than the needs of people. This creates a paradox where public space is not truly public but rather a controlled and regulated space that reinforces existing power structures.

In short, as HEAVY DUTY, we drop our sculptures on the street and within hours they are gone. Never to be seen again. An action that was never intended as the original act of resistance but has become a common thread in our work. One way we fight this is with timing. Everything we do is done in the early hours, while you are sleeping. Our sculptures would never see the light of day if not for the cover of night. It goes something like this:

Phone rings

“… hello?”

“Are you up?”

“… what? Oh yeah. Let’s go.”

[When taking back your public space, blend in. Wear your urban

camo (fluro vest) and boots. Look like you know what you are

doing. For extra points look pissed off with the fact you even

have to do it. And if you get stuck, say ‘it’s for a uni project’]

What is interesting is that in some ways the public is prohibited from accessing or shaping public space. We do not really have a choice in how these spaces are planned, how they look, or how they are used. This is a system that is so layered with red tape that makes sure that ‘having a say’ does not have true influence. Reply to a survey. Email a local member. Fuck, even go to a council meeting. My experience is that the public voice goes unheard. So, our answer? Stop asking politely and do it without permission.

Deforestation Detour, 2021.

HEAVY DUTY, The Shelter Seat, 2020.

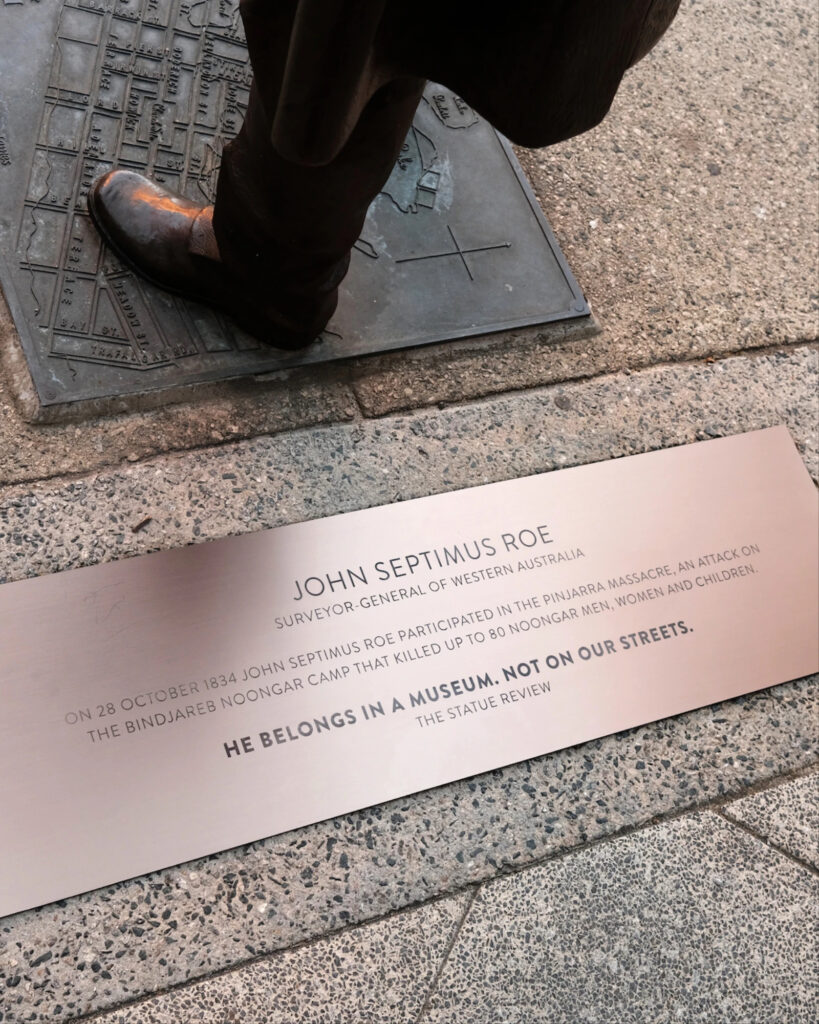

The Statue Review, 2020.

Whilst it can be disheartening to have our work so quickly removed, it lives permanently online. There are important notes to be made about the benefits of temporal art installations in public space. Specifically, those installed without permission.

Experiencing temporal art in a public space can be disarming. In its nature it is unexpected and exists only for a limited period. By creating installations or performances that are site-specific and engage with the physical and social environment of the public space, we are able to facilitate conversations and encourage the public to reflect on a particular topic in relation to the space around them. With permanency and permission, we would lose this.

In order for public space to remain public, individuals need to not only engage with it but demand it. People have a right to the city.2 This is a right that needs to be exercised or it will be taken away. The key is public participation.

We need public space that welcomes expression, free of unreasonable restrictions. In a successfully functional public space expect to see, smell and feel things that potentially result in momentary discomfort. This is good! These are connections being made with and to the people and places that culminate in forming this environment that you are in. This is community.

modified 12 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kings_Park_Western_Australia.