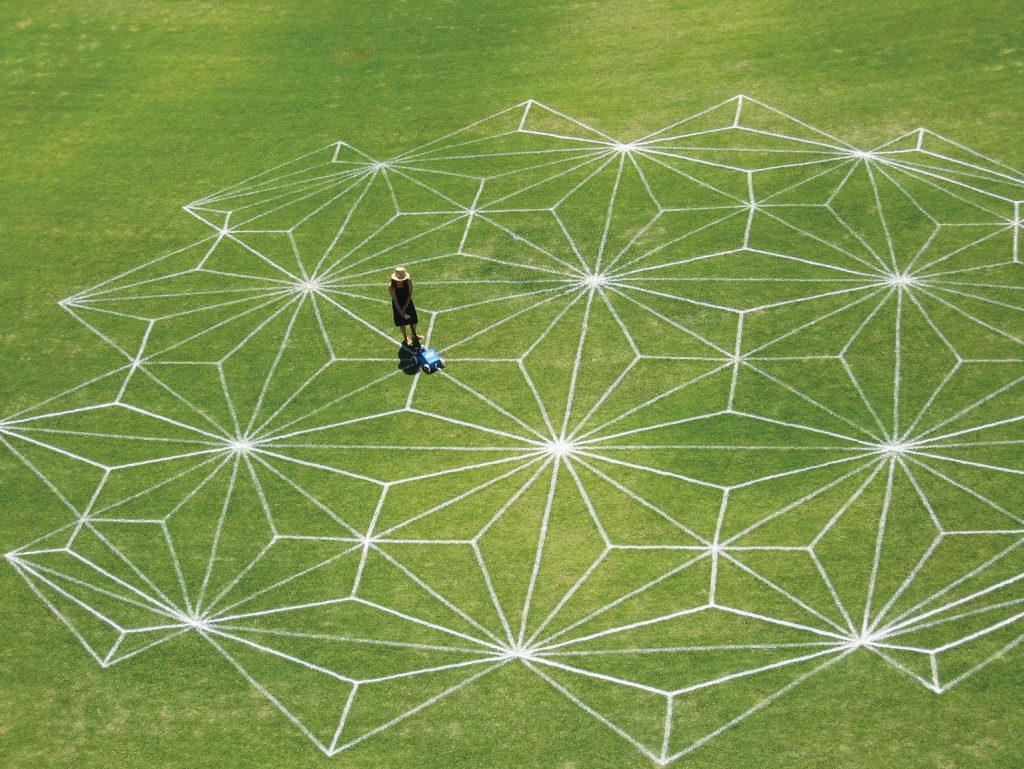

Field drawing #1 2008

bio‐paint and sports field line marker installation view

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Photo credit: Julie Nixon

Design has become something of a lingua franca for the present. Design artifacts — both custom-made and mass-produced — are widely acknowledged as prime agents of ideology, identity, social distinction and meaning. Designers are highly adept at leveraging aesthetics to create heightened desire and depth of experience, but only a few outlying areas of design use design artifacts reflexively to examine design’s nature and purpose.1 Mainstream design is linked to commercial, technical and utilitarian objectives. It is mostly visual artists who critically examine the nature of aesthetics and practices, and their role in structuring contemporary experience. This essay discusses the work of four such Melbourne artists — Melinda Harper, Anne-Marie May, Rose Nolan and Kerrie Poliness — whose work since the early 1980s has navigated a liminal zone marked out by the discursively constituted fields of art, craft and design, exploring the heterogeneity and boundary crossing around aesthetic practices.

When postmodernism broke in Melbourne in the early 1980s, it came in the form of a range of historicist styles, appropriation strategies and blunt proclamations about the end of art, authenticity, certainty, depth, history, meaning and so on.2 Debates around postmodernism attributed little value to the pursuit of art for both artists and society. With alienation and anomie nominated as the primary social forces in late capitalism, engaging in bad-faith textual play with exhausted cultural materials was all that was assigned to contemporary artists to do. In separate and allied ways, Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness, who were participants in the artist-initiated exhibition venue Store 5 (1989–1993), embarked on a different path, seeing genuine meaning and scope for resistance in a practice grounded in basic forms, materiality, non-representation and processes.3

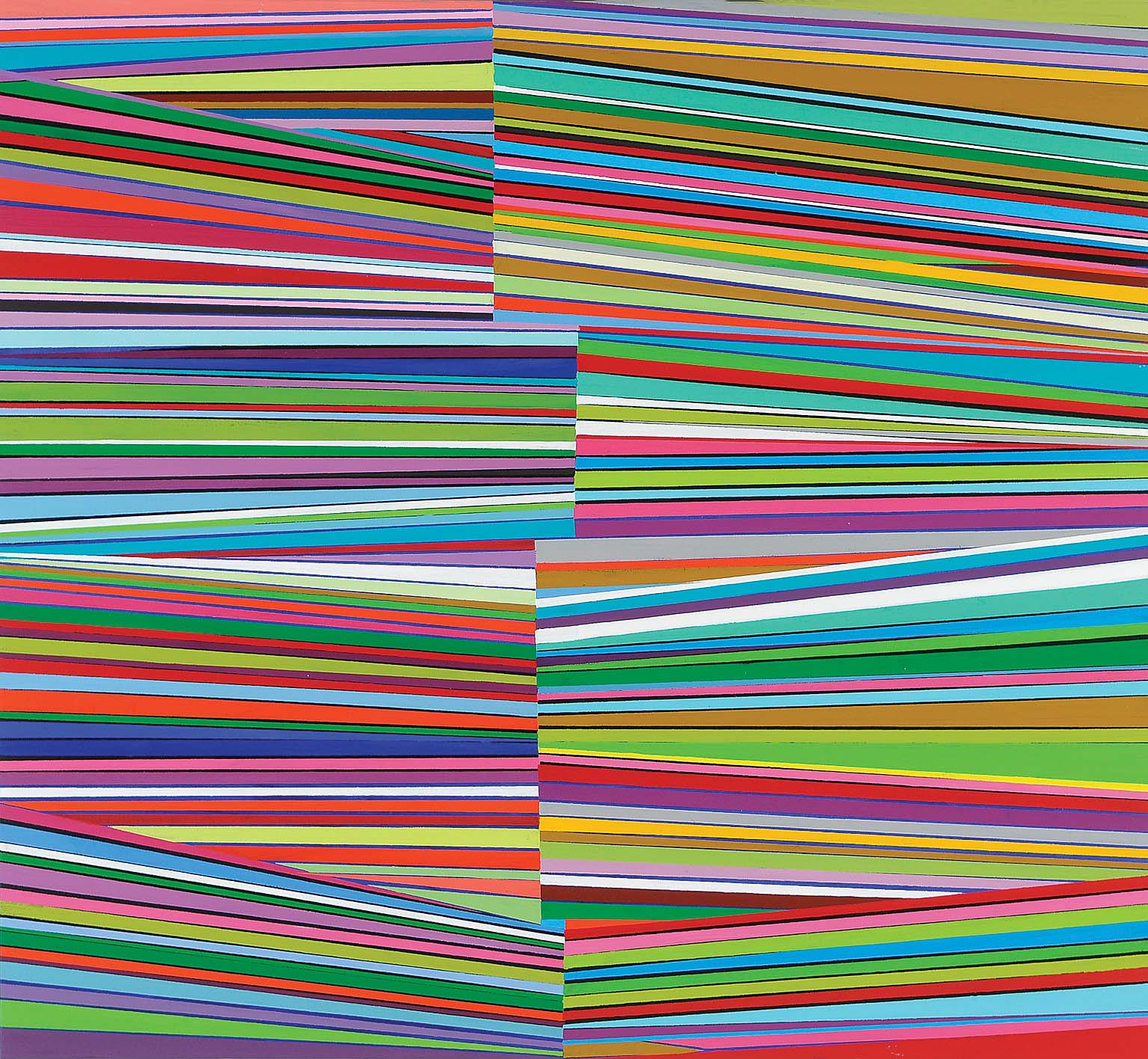

From the perspective of the present, it is possible to see the prescience in their focus on practices connected to aesthetic production and the perceived distinctions between them. Several decades of academic theory has stressed the role of artifacts and contexts (the media, the shopping mall, the art gallery) in the systemic construction and economic exploitation of meaning and human desire.4 Lately, however, a strand of social inquiry has begun to investigate the meanings embedded in practices, detecting more than the oppressive effects of social-structural forces within what people do.5 An important impetus for this analysis has been Pierre Bourdieu’s discussion of the schemes of perception, action and understanding that frame relations within fields of practice.6 The work of Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness explores the contingency of practices within and across cultural categories, highlighting the multiple forms of adaptation and mixing that mark their use. Harper’s and Poliness’ work traverses a complicated line between abstraction and pattern, recognising the place of the decorative in the development of abstract art. Harper’s work pits a strong decorative inclination against aspects of formal disjuncture and negation, tempting descent into non-art practices, such as design. Poliness has long used a diamond motif and a standard decorative vocabulary of repeated motifs, varied colour and symmetry, combined with everyday processes, such as spray painting, to generate a body of work that tests the values of canonical abstract art. Recently, Poliness’ critical interest in the ideological dimensions of practice and production has led her to include participatory processes in the realisation of her wall drawings, resulting in a range of people helping to define artistic outcomes.

Each of the four artists regularly conflates elements from the domains of art and non-art (craft, decoration, design and ornamentation). Harper uses long-stitch embroidery to make abstract works. May has used fabric and fibre, combined with processes of cutting, gluing and wrapping to the same end, exploring the locus of skill and accomplishment in everyday practices. She has also produced non-objective works in the form of carpets and a set of wall works in the form of cloth bags made from tie-dyed fabric. Nolan has long worked with cardboard construction, currently using hand-cut cardboard and hand-painted hessian to produce three-dimensional environments, room dividers and elaborate door surrounds incorporating repeated floral motifs. She has also produced carpets and cloth banners in addition to wall works comprised of text. Historically, wall paintings have blurred the boundaries between fine art and decor; Nolan’s handling of text increasingly pushes words towards pure visual form.

May could be speaking for all four artists when she highlights her interest in working with elements that ‘have meanings and associations outside of art’.7 In exploring the boundaries of art and non-art, their work raises diverse questions about the role of aesthetics in structuring and mediating everyday experience. This involves risk. As women artists, some elements of their work could be seen to reflect a feminised, decorative impulse, except for the presence of counterbalancing features. Each has often used materials that could be described as ‘poor’. Their work plainly states its production processes, although the strong sense of the handmade — in representing a specific economy of production — reinforces the link to the realm of everyday life.

Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness took up abstraction at a time when it was widely seen to be emptied of any purpose other than to expound the failures of modernism. Established artists in their immediate milieu, notably Lesley Dumbrell, Robert Jacks and John Nixon, demonstrated an alternative stance. Also influential on their interest in abstraction was the work of women artists of the historical avant-garde such as Natalia Goncharova, Olga Rosanova, Lyubov Popova, Vavara Stepanova and Sophie Tauber-Arp. These were artists who sought to make a practical contribution to society through the alliance of radical aesthetics and human need. However, their work in both art and areas such as garment, graphic and interior design, in which styling and visual qualities dominate, arguably resulted in their subsidiary place in the history of modernism. Collectively, the work of Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness exhibits a strong historical consciousness. Each artist has found significant scope for further investigation in the divergent and often only partly realised impulses comprising modern art. Their work refutes stereotyped modernist values of universality and transcendence to explore how aesthetics and practices are articulated and experienced in the everyday, exploring the contingency of cultural practices and the influence of discourses, judgments and perceptions over how aesthetic entities are constituted and framed.

In Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste, Pierre Bourdieu identified a range of dispositions, including skills and sensibilities, to be the currency of cultural and social meaning.8 For Bourdieu, the storehouse of tacit knowledge bound up in practices is integral to the instantiation of cultural capital in social life. Others have written of the formative role of artifacts in practices of viewing and listening.9 As a range of dispositions, the centrality of the hand-made in the work of Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness and the way they adopt and adapt materials explores relations between fine art, craft, homemade work and professionally realised artifacts. None of the four artists passes the fabrication of their work over to others, suggesting an interest in the neglected, but often consuming, routines of daily life. Ben Highmore argues that the widespread routinisation of work practices that grew out of modernity resulted in routine being seen ‘as an experience of deadening repetition’.10 However, he also highlights the ambiguous meanings in routine, especially in domestic settings where it is associated with both drudgery and the caring and comfort of affective labour.

Hand production in the work of Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness reflects mundane forms of creativity normally viewed as non-aesthetic, time spent in production being an important aspect of their engagement with and experience of art practice. Harper chooses to work in oil paint even though using acrylic would make it much quicker to execute the many adjacent areas of colour in her paintings, slowing down the painting process, making aesthetic decisions more measured. May currently works with Perspex, using an involved and hard-to-control process of hand-bending. Nolan’s large-scale installations involve arduous manual work, even though most viewers would assume their cardboard components were machine cut. Poliness establishes the conceptual premises of her work, including writing highly detailed manuals for the execution of her wall drawings, and then produces many repetitions to see what results. As much as the nature of production is central to the meaning and experience of the work of Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness, it also explores hierarchies of cultural dispositions and distinctions. The choice and use of forms, materials and processes operates reflexively from an epistemology and ontology of the relative; often incorporating judgments around good and bad aesthetic performance in a way that somewhat counters modernist values of aesthetic progress, purification and transcendence. To borrow some key terms from Bruno Latour’s discussion of the illusory nature of modernity, rather their work revolves around practices of hybridisation, mediation and translation.11 This is exemplified in Nolan’s large-scale text works, for instance not so sure this works 2005, less is harder 2008, hard but fair/pointless 2009, awkward 2011 and over and over/again and again 2012, in which any sense of the heroism or transcendence is undercut by their written content.

Both art and design have been identified as primary markers of elitism and alienation. An aim of the historical and neo-avant-gardes was to erase the divide between art and life by rejecting the rarified characteristics of traditional art. Yet vanguard artists’ philosophical goals have often clashed with the actuality of modern life, which they sought to reform, or only selectively embrace, choosing factories and machines, for example, over the goods they produced. Key proponents of modernism railed against popular taste, especially what they perceived to be the anachronistic and false character of modern goods. In his provocative 1908 essay ‘Ornament and Crime’, the Viennese architect Adolf Loos linked decoration to moral failure.12 Le Corbusier rejected the ‘conglomeration of useless and disparate objects’ in middle-class homes, which he described as ‘intolerable witnesses to a dead spirit’.13 Later, the formalist art critic Clement Greenberg observed that, ‘Decoration is the specter that haunts modernist painting, and part of the latter’s formal mission is to find ways of using the decorative against itself.’14 The emphasis in modernism on the status of artworks as things-in-themselves influenced the idea that form in modern design should give primary recognition to functions, albeit functions based in rational needs.

By comparison, Mike Featherstone argues that ‘aestheticization in terms of fashion, design, food, music, etc.’ sits ‘at the heart of the modern everyday’, with stylisation comprising its essential fabric.15 Over nearly three decades now, the work of Melinda Harper, Anne-Marie May, Rose Nolan and Kerrie Poliness has explored the situated, performative nature of aesthetic practices. Where discourses around contemporary art following modernism reduced artworks to the status of conduits of meaning, or worse, mere symbols of the complete impossibility of meaning, Harper, May, Nolan and Poliness have harnessed the agency of aesthetics, materials and practices to explore the dominant discursive frameworks around cultural fields. Their work extends beyond critique to contribute something constructive in its own right. The intense formal character of the work of Harper and May resists shrinking sensory experience in the present. Recently, Poliness has begun to use colour-coded, diagonal grids to document the wildflower species of western Victoria’s volcanic plains, drawing attention to the visual and biological diversity of a highly endangered ecosystem, while her participatory wall drawings highlight the general collaborative dimension in art, suggesting the reciprocal relationship all artworks have with their viewers. Nolan’s transformation of arrays of elements and ideas into whole environments brings their audience into direct contact with a range of embodied and psychological states and forms of tacit knowledge and understanding, including aesthetic knowledge. All four artists explore the productive tensions between hegemonic, disciplinary conceptions and uses of aesthetics, highlighting the structuring relationship between aesthetics, affects and the everyday world.

Dr Carolyn Barnes is a Senior Research Fellow in the Faculty of Design at Swinburne University of Technology.