edited by: Chris Kraus

Chris Kraus is a Los Angeles-based author and critic, founding editor of Semiotext(e)’s Native Agents imprint and onetime filmmaker in the New York downtown scene of the mid-eighties. Her novels — part-fiction, part-memoir and part-philosophy — include I Love Dick, Aliens and Anorexia and Torpor. Kraus has written three books of art criticism, Video Green: Los Angeles Art and the Triumph of Nothingness, LA Artland: Contemporary Art From Los Angeles and, most recently, Where Art Belongs.

I

Invariably, if you project a film against the same wall everyday, the film stock will erode long before any light impacts the wall. Projection is a vain illusion; it can never truly know its object.

We’re in a room that looks to be someplace ordinary, a classroom, lights-out. Grainy, high-contrast close-ups of a bored audience cut with a woman in black underwear pacing out a silent monologue — performing, flaunting her femininity. On the voiceover, David Rattray does Artaud — over-identifies with Artaud: ‘maybe I entered into a black hole of personally identifying with Artaud in ways that I had no business doing — it’s an occupational hazard’.1 He translates texts with the risky conviction of the method actor. The threat of involution attaches to the woman by cinematic inference (because to edit is also to translate in the end, to catalyse through organisation). Her masquerade holds femaleness at a distance, yet the risk that she will lose herself in the role remains.

The biggest danger, that of losing oneself, can pass off in the world as quietly as if it were nothing; every other loss, an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife, etc. is bound to be noticed.

— Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death

[On the next screen over, callous long takes of burned-out characters talk SM in their daily goings-on. Detached seeming, cool, they pass cigarettes between them or the same cigarette twice. It’s tenement noir, raw, dark stuff. But mild in a sense too — ringing a bit hollow and somehow tame. It seems the more hyperbolic the masquerade the less real the danger. Now a quote from literature. Now ants eat a dead face. Snuff? No, transgressive-chic: street nous cross academe. Elliptical flows. Pulse electric green of fading 16 millimetre.]

II

Where to start? If a woman speaks, by default she speaks with the voice of a man. So to speak (write) in a minor voice — her own voice — is thoroughly, necessarily, political; even revolutionary. A minor use of language compels it to unfamiliar places: uncompromising and uninhibited, you (Chris) drag language through monstrous-excess-of-female-abjection, all mess and emotion, to the very threshold of becoming-woman. You force language to articulate the alien realms of female inner-life and refuse to shroud any of it in euphemism or couch it in the demure terms with which we’ve been consigned.

Because it is innately political, everything in a minor literature assumes a shared significance, ‘a whole other story vibrates in the individual concern’. The individual speaks in a collective voice and the text becomes a ‘collective assemblage of enunciation’.2 Simply, you speak for us: I read your radical narrative and I can relate. Your structural experimentation resounds in me. I identify. Oh, I hum with recognition!

Halfway through I Love Dick, Chris drives across the America of our collective conscious and stops at Cadillac Ranch, just outside of Amarillo, Texas, on Route 66. The Cadillacs make her think of Dick, she says and seems to swallow, right there and then, the whole cowboy mythology of it all. And I — I feel just like I know exactly how she feels. I’ve read On the Road and fantasised I’m Jack Kerouac along with every other young hot-blood idealist. I am at once myself and I am other.

III

Not only do we relate, but in relating, project:

When finally you spoke, Chris, a few of us felt funny after. We came together to wonder collectively whether this Chris was the real Chris? On stage you seemed so different to the Chris I kept in my head (from the books, and now also from the films). You hadn’t come across as the hard-boiled feminist intellectual I had you pegged as. [I had her pegged as.] You skimmed the surface of questions and flirted, you seemed girlish. And flaunting it. I felt deceived.

Chris Kraus is unconcerned. Hers is the kind of work that thrives on misplaced assumptions and it seems only to advance her purpose that we find it difficult to read (judge) her. ‘Because we rejected a certain kind of critical language,’ she writes (elsewhere in Dick) ‘people just assumed that we were dumb’.3 Do first impressions still count for much if they reveal more about the spectator than the spectacle?

The persuasive weight and immediacy of her experiments, narrowing the gap between art, and theory and life, become thus apparent. ‘Dick, you may be wondering,’ Chris writes (back in the desert), ‘if I’m so wary of the mythology you embrace, why’d my blood start pumping 15 miles west of Amarillo?’4 Because she’s performing, she reveals, ‘…“scrambling the codes.” Oh Dick, you eroticize what you’re not, secretly hoping that the other person knows what you’re performing and that they’re performing too.’5

Ok, so develop different literary/filmic personas. Role play, unfix subjectivities to confound objectification. Enact a schizophrenic becoming-female to undermine other people’s readings of your body. The Chris on stage is a dramatic foil to Chris the intellectual, Chris the writer is different again to Chris the auteur and each is also real; a genuine component part of a complex subjectivity endlessly performing its philosophical position (The real work?). But more — and here’s the common thread of this expanded practice — it’s life as the material for art, viewed at the cool remove of philosophy. Female privacy, self-debasement, ‘shameless emotion’ turned strategy; turned form.

‘Why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our own debasement?’,6 Chris asks.

No one has the balls to respond.

IV

There is masochism in over-identification sure, the threat of losing one’s self in the image. (Rattray-becoming-Artaud.) But there’s something else besides: What impact does identification have upon the object of our fantasies? What when the projected image outlasts the wall?

In a minor literature, the social and political interests under the surface of a narrative well up to subsume the individual’s story. For the second time, the author’s voice is not her own, speaking not with the voice of a man, but with that of the multitude. The author becomes asubjective (as if we could take a knife to language without injuring the speaker!). And this seems at odds with sustaining the image of complex subjecthood that was so important to communicate in the first place. If you put something out there, and people respond — respond so hard they ‘make it their own’, so to speak, then where does that leave you, Chris? What is the death of the author, when you offer yourself up as the work?

It is a matter I think of degrees. The complex problematic of maintaining an appropriate distance is a question of shades and nuance that is of vital and utmost necessity. This gap, little more than a breath, between Chris-of-fiction and Chris-in-fact is alone that which resists asubjectivity. The challenge demands a certain control over the game, to keep oneself always at one or two degrees’ remove from the roles one plays while never allowing it to descend into masquerade. This then, to me, is the most revelatory feat of the work — because it is only from within those few degrees, at such precarious remove, and with such high stakes, that a revolutionary voice can issue with such clarity.

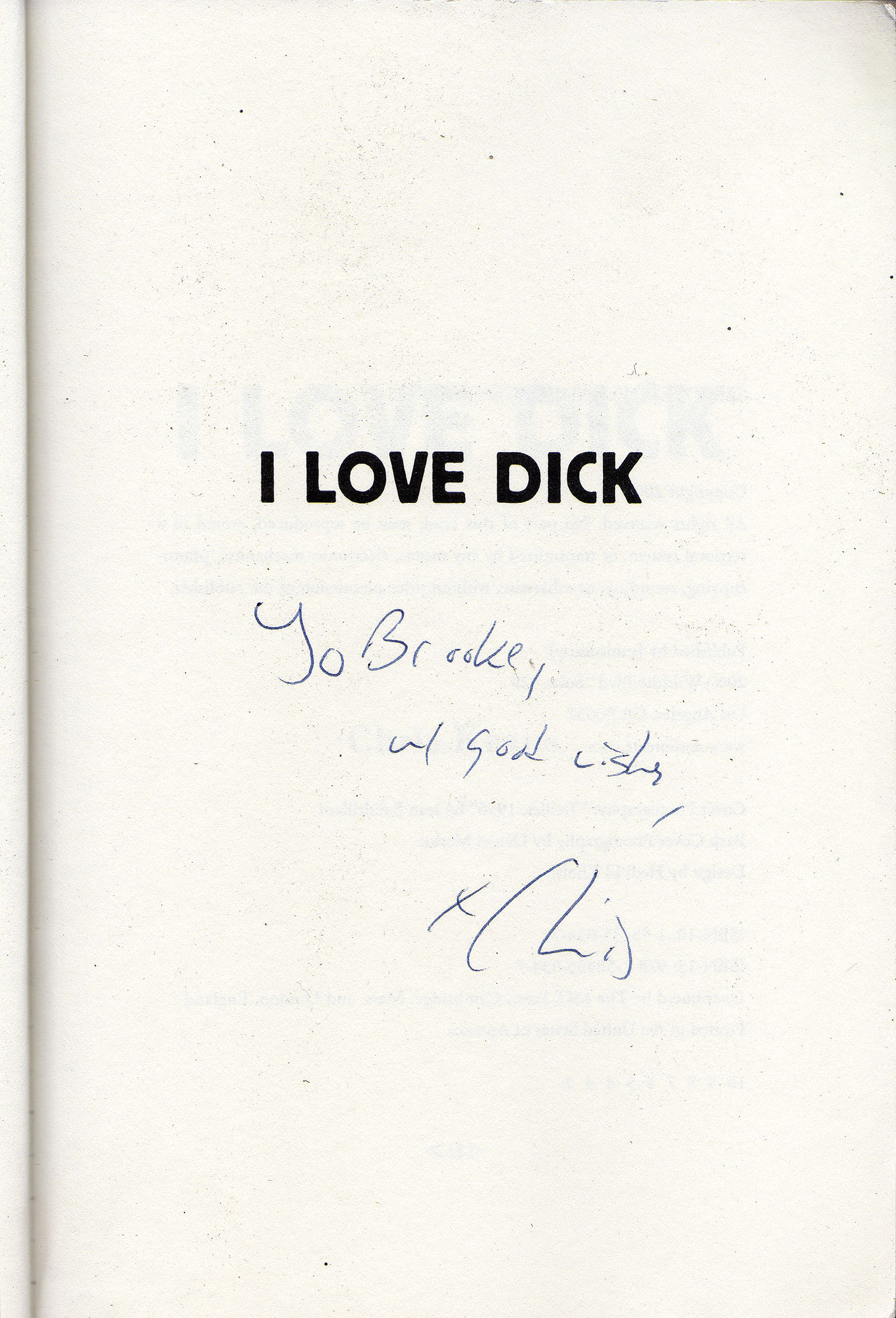

Brooke Babington is a Melbourne-based artist, writer and curator. She is also a fan.