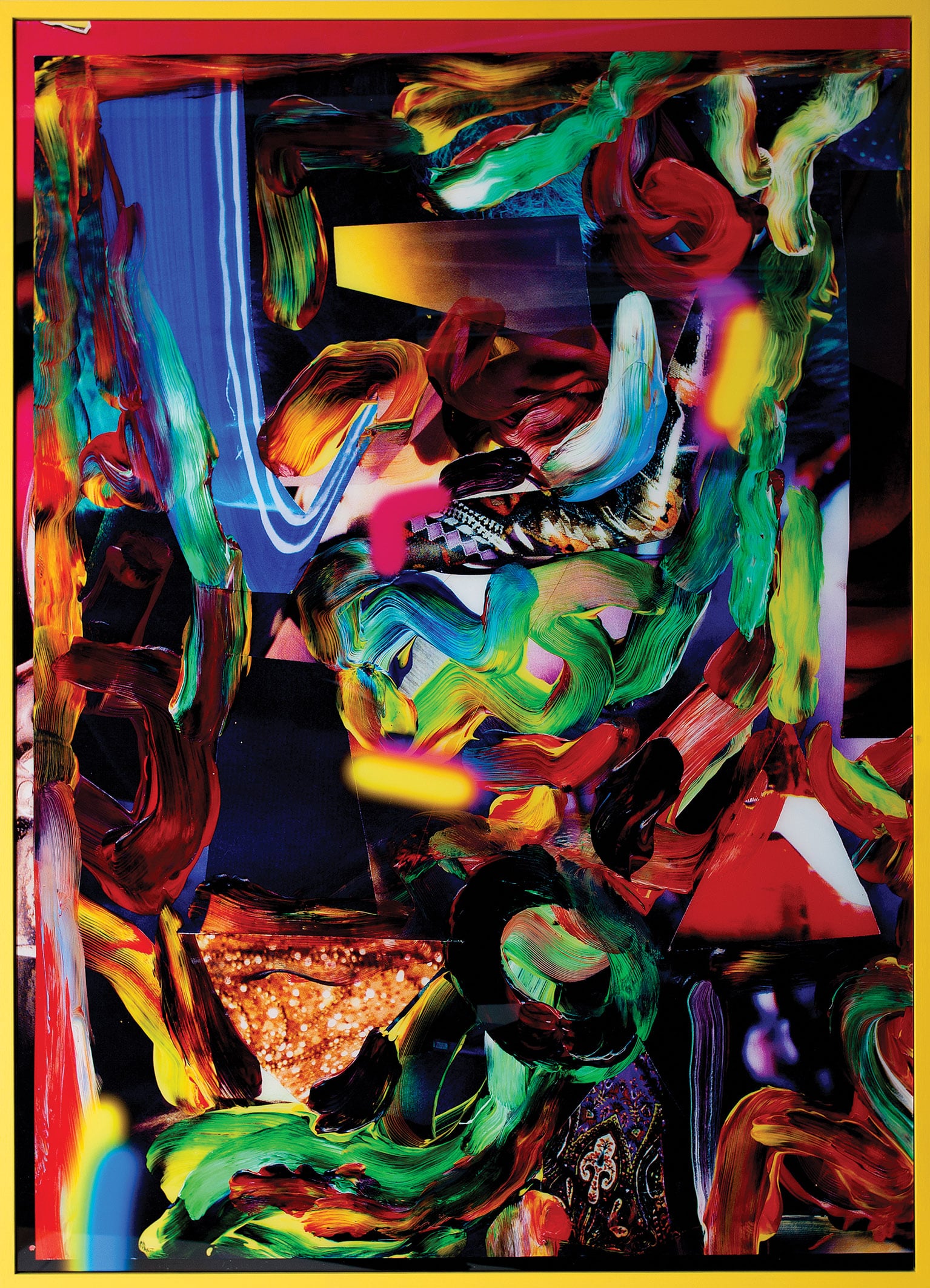

Spiritus Mundi 2012

fabric, wadding and polyurethane

Image courtesy Neon Parc

Photo credit: Geoff Newtown

I’ve learnt that it’s dangerous to mention I spent the first twenty-something years of my life living in ‘The Emerald City’, for it invariably leads to the question that seems to fascinate Melburnians of all ages, races, genders and creeds: ‘how do the cities compare?’ An innocent enough question, perhaps, but it is typically asked with only a thinly veiled mandate that my adopted hometown emerge as far superior in all regards. I’ve been subjected to the full litany of clichés; most boil down to the sentiment that Sydney is beautiful, flashy and vacuous, while Melbourne is cultured, introverted and artistic. Oh please, give me a break! These types of distinctions seem rather arbitrary, if not a tad neurotic.

Still, over the years of living south of the border, I have begun to formulate my own observations about the differences between the kinds of art practices emanating from the two capitals. These variances are not defined by content or medium, but rather the manner in which they are handled. A large number of works emerging from Sydney’s art scene seems charged with a playfully decadent abandon. More than the embrace of plucky aesthetics, it is the ‘in your face’ attitude that seems to define this approach. Many of the works I’m thinking of seem to take a certain pleasure in subjecting their audience to a sensorial assault, enacting a kind of creative ‘sadism’. In contrast, much of the work I have recently seen coming out of Melbourne seems to have a more earnest intent, conceptualising art as a vehicle for working through political or social issues. This propensity to take on the troubles of the world is something that might crudely be labelled artistic ‘masochism’.1

So there it is, my tentative hypothesis on S&M.2 Of course, only a true masochist would posit such sweeping generalisations — all the same, the influx of Sydney artists exhibiting in Melbourne at the start of 2012 provided an irresistible opportunity to test out this proposition. And what better place to start than with TV Moore’s Colour Drunks at Kalimanrawlins. Highly celebrated for his video works, here Moore presented a series of works on paper in what might best be described as a primitive discothèque aesthetic. An orgy of iridescent spray paint and thick gestural marks; lurid pigments had been applied in a mock naive style over snatches of magazine print. But all was not quite as it seemed, on closer inspection the works were revealed as photographic reproductions, the enticing promise of textural depth suspended in their silky smooth surfaces. There was something rather perverse about the way these prints, which so vigorously denied access to the artist’s hand, were specifically paired with hand-painted frames.

Loose, woolly figures emerged out of the psychedelic muddle in many of the works. Breaking from the more opulent tone of the rest of the exhibition, 3 Micky’s 2011 offered a blocky portrait of the ‘King of Pop’, repeated in three near-identical parts. Jackson seems a perfect mascot for the show. Living most of his life in the media spotlight, he was the kind of creature that seemed most at home in the two-dimensional realms of glossy magazines and television screens. Offering only simulation of texture, gesture and expression, Colour Drunks was a potent celebration of surface and superficiality. While the photographic film contained the gestural chaos threatening to explode within the works, Moore’s many references to forms of intoxication suggested a number of options for inoculating oneself from the threat of emotional turbulence. We might glimpse the vortex but we will be numb to its effects. This glistening world of shallow delights was simultaneously hypnotic and creepy, delicious and disturbing.

But let me be clear, I do not wish to mimic the inane quip that Sydney is the ‘dumb blonde’ to Melbourne’s ‘brooding intellectual’ by suggesting that artists from the north are only interested in surface detail. Clearly, many engage with pressing political or social concerns but when they do they tend to take on a more defiant, mischievous stance. Take The Kingpins’ exhibitions at Neon Parc, for example. Here the drag quartet brought forth a vision of the apocalypse. With the threat of climate change dogging contemporary consciousness, what could be more serious or topical? But in The Kingpins’ bedazzled hands this calamitous scenario is converted into a rebellious romp.

Riffing off William Butler Yeats’ celebrated poem The Second Coming, the troupe served up a tropical island-themed ‘Day of Reckoning’.3 The scene was set by a handful of assembled sculptures. In one, an oversized leg wrapped in a tantalising mane of synthetic, rainbow-striped hair penetrated the ceiling, miming the authoritative stomp of a wrathful disco god. In another, a black milk crate appeared to have been hurled from above, pinning a figure to the floor. Its splayed legs and placid phallus poked out from beneath the bulbous mass of a garishly patterned beanbag. Watching over these events were two inverted photographs of the kind of exotic idol you might imagine Frieda Kahlo dreaming up while dropping acid in Hawaii.

But it was in the video work The World 2012, in which we really started to glimpse the anarchy Yeats foresaw being ‘loosed upon the world’. Masters of détournement, The Kingpins co-opted a canned promotional video for a plush Gulf state island development, overlaying it with the antics of a dizzying ensemble of characters spawned from a range of iconic pop culture references. A handlebar moustached reggae musician, a pair of demonic title fighters and a Peter Allen-esque piano player all made an appearance. At one point, the four members of the group, decked out in Hawaiian print leisure suits, huddle together, their engorged faux penises metaphorically fucking an image of the globe. The pointed setting and camp performances alluded to a variety of triggers for the world’s demise — mass consumerism, the pillaging of natural resources, even religious and cultural tensions between the Middle East and the West. Yet our fears were quelled by the intoxicating pleasure of this fantastic vision of the world on the brink of collapse. Whatever the cause of Armageddon, The Kingpins are seeing us out with a bang!

Tom Polo’s exhibition at Gertrude Contemporary might appear relatively introverted when compared to the spectacular posturing of The Kingpins, but we can detect a similarly debauched deflection of anxiety in both practices. Polo has built a career on a light-hearted, exaggerated display of self-doubt ciphered through the act of art-making. True to form, Gestures and Mistakes was a grand-scaled meditation on failure, played out via a performative approach to painting. A backdrop of shaky markings and unresolved forms in a vibrant palette flooded the entire front gallery space. Banners and placards dispersed haphazardly throughout appeared to give voice to the artist’s angst-ridden psyche. Slogans such as ‘tryharde|rtotryl|ess’ or ‘Self|confi|dens’ emblazoned in shonky script acted as feeble prompts for a fragile ego and clashed with the more defeated ‘Self|sabbo|tage’ and ‘Balls’. Other placards were decorated with Polo’s signature portraits of misshapen heads rendered in jagged outlines and muddied tones. These forlorn characters appeared to embody the artist’s failed vision.

Gestures and Mistakes was an exhibition in a state of flux, its painted surfaces continually worked and reworked to the point of exhaustion. At the exhibition’s opening Polo could be found in the gallery’s window, restlessly amending the large-scale wall painting that filled its frame. He drafted gallery staff to alter the work further throughout the course of the exhibition, emailing them instructions on how they were to amend the installation. At one point, staff were commanded to paint over the lettering ‘Gestures and Mistakes’ which occupied the front window, at other times they were instructed to add their own paintings to the gallery walls. While a droll articulation of artistic uncertainty, these ongoing interventions went beyond a simple embrace of the neurotic nature of the art making. Polo seized this kernel of self-doubt and projected it outwards, joyously inflicting its affects onto his audience. The viewer was destabilised amidst this sea of vacillating indecision, their expectations of a coherent, resolved work actively flaunted. Conjuring up and externalising the twin drives of ambition and failure, Polo ensured it was his audience who was ultimately left with an uneasy sense of performance anxiety.

Like his fellow Sydneysiders, Polo took great delight in the salaciously sadistic excesses of his show. But what might we compare this too? Melbourne-based artist Nicholas Mangan’s Some Kind of Duration was showing concurrently at the Centre for Contemporary Photography and provides a striking contrast to the aforementioned exhibitions. Here an austere Canon NP6030 photocopier cast in concrete sat under the glare of a florescent light. An icon of the post-industrial era, the crumbling facade of this solitary object appeared like the relic of some lost civilisation. Its staged deterioration seemed a bleak prophesy of our world in decline. In accompanying video works, themes of decay, obsolescence and redundancy established connections between the photocopier and the complex histories of the now-demolished Walter Burley Griffin Pyrmont incinerator and a Mayan ruin in Mexico — a multi-pronged study of entropy in action. It’s here where Mangan’s masochistic inclinations are revealed, the beaten down form of his work suggesting the heavy burden of his determination to fight the tides of time and keep these histories from slipping away.

So, on the evidence provided, it appears that my thesis holds true. Of course, my choice of examples is just as capricious as any of those used in support of the more general comparisons made between Sydney and Melbourne. Nevertheless, the convergence of a particular set of exhibitions that kicked off the art year in my neighbourhood meant that for a brief instant, I had the immense satisfaction of feeling completely justified in my conjecture.

Shelley McSpedden is a Sydney born, Melbourne-based, writer and educator.