This year’s annual Kinetica Art Fair, hosted by the Kinetica Museum in London, attempted a balanced representation of analogue and digital art practices. In this way, the 2012 event marked a break with Kinetica Art Fairs of years past, which have traditionally privileged the display of digital media. For Kinetica Art Fair 2012, ‘kinetic art’ was an open and expansive term that embraced artists from across different media who were broadly interested in the effects of sculptural and spatial movement.

Defining ‘kinetic sculpture’ has been a longstanding polemic within contemporary art circles. Kinetica’s curatorial decision to focus on heterogeneity within the form and to move it away from the new/old media binary was perhaps made partly out of frustration with the mainstream media describing its past art fairs as, ‘walking into a magical toy shop’.1 Widening the breadth of the exhibition might also be an attempt to widen the conventional perceptions of kinesis and encourage more media art experimentation.

Historically, the term ‘kinetic’ has held a lowly status within the contemporary art world, at the very least since Time magazine referred to it in 1966 as the ‘kinetic kraze’.2 Jack Burnham in Beyond Modern Sculpture quickly determined that artists working with analogue movement were outdated and misguided, working as they did in an emerging information society.3 For Burnham, these outdated artists could never compete with the increasingly popular dematerialised systems aesthetics developed by conceptual and digital artists of the day.4 Since then, attention to physical movement in art is often made within an evolutionary narrative — analogue kinetic art is widely considered a mechanical ancestor of contemporary digital art. The 2008 Biennale of Sydney: Revolutions – Forms That Turn was one such event that included spinning and whirring modern avant-garde works to remind us of how much media art has changed over time.

The Kinetica Art Fair 2012 presented a Duchamp-styled bicycle wheel fitted with xylophone keys, drawing contraptions directed by swinging pendulums, subliminal dream machines, architectural models for train stations, public light orchestras and UV light installations. Viewers walked through the cacophony of sounds, movements and strobes in wonderment of the various interactive opportunities. ‘Kinetic’ is often mistaken as a historical phase solely restricted to mechanical movement; however, as evidenced by Kinetica’s art fair, kinesis also has a strong history of experimenting with actual, virtual, relational and communicative movement in real time that has not been forgotten. Arguably, interactive art has become second nature for most contemporary audiences, who are today highly attuned to motion in art both in and outside of conventional exhibition spaces (considering this, perhaps the experimentation with the effects of motion in art succeeded a little too well).

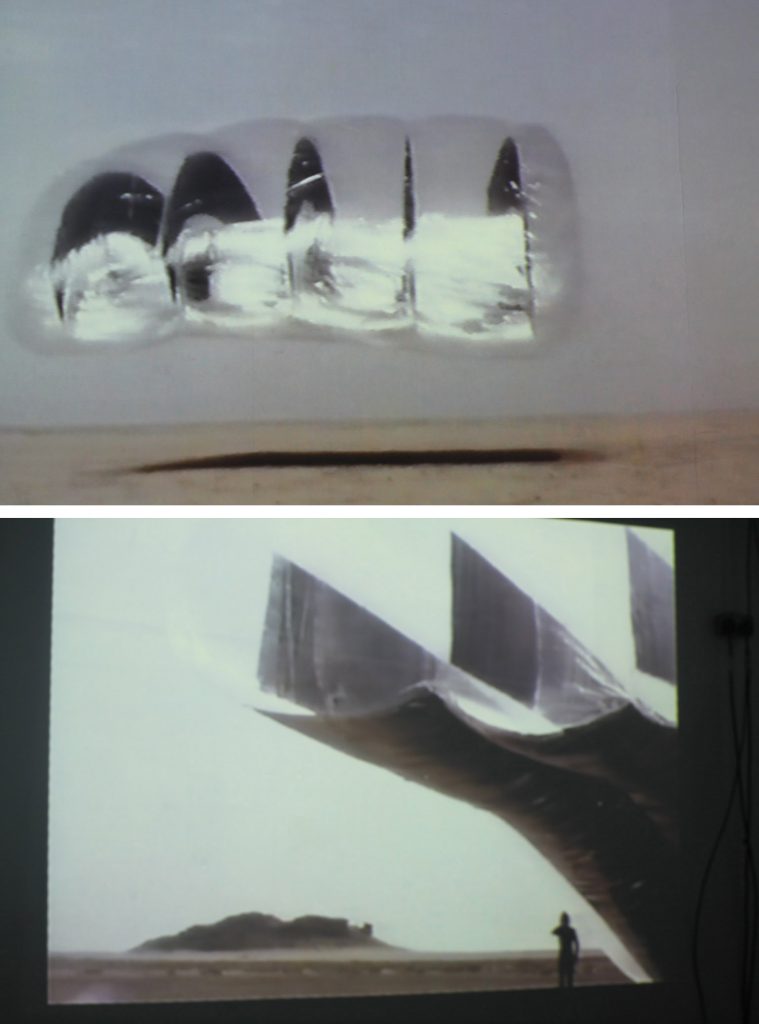

As part of Kinetica, British artist Graham Stevens introduced a number of his films: Atmosfields 1972 and Desertcloud 1974. These films are documentary montages of Stevens’ early works; predominately participatory inflatable pneumatic works installed in public spaces with segues of texture studies, weather systems and planetary zones. One sequence that stands out amongst these is the silent documentary footage of Desertcloud. Filmed in a desert near Kuwait, the frame slowly pans across a barren horizon. Gradually coming into the frame is an arching silver inflated bed, waving and hovering four to six metres high in the sky. Entering the frame, Graham Stevens himself walks underneath the Desertcloud and spends time sitting in its shadow and looking above; he then stands and walks towards the camera.

The Desertcloud, having minimal structure, hovers like a kite in the air — no sign of motors, pulleys or cranes to enable and sustain its height, it simply hovers with a few grounding ropes to prevent it from flying away. Desertcloud was produced as part of a series of projects by Stevens in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a means to explore the transformation of energy in weather systems (particularly evaporation, condensation and precipitation). Like Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cubes 1965, Stevens’ inflatable works were their own self-contained weather systems. Unlike Condensation Cubes, which were exhibited within the gallery, Steven’s inflatables were less autonomous and reacted to the outer weather patterns of the landscapes that they were situated in. Lined with reflective material along the underside of its belly and clear sheeting across its sides and roof, the Desertcloud negotiated the potential for collecting moisture from the air, even in arid areas.

Prior to Desertcloud, Stevens was known in London for his utopian participatory pneumatic works. Amongst these were works that enabled humans to walk on water, inflated balls that were thrown around for relief during political protests in Trafalgar Square and immersive colour domes that altered the veiwer’s perception of colour. Heavily influenced by the utopian futurology of Buckminster Fuller, Stevens is amongst a community of artists that proposed various forms of co-habitation between society, ecology and technology. While pneumatic structures were suggested as alternative objects to be used for entertainment and transportation, for Stevens’ experimentation with pneumatics, inflation and participation also formed potential solutions in times of ecological change or uncertainty. Stevens encouraged interacting with these structures with the intention of expanding the perceptual field of the corporeal body, bring forth new perceptions and interactions with the environment and therefore potentially new understandings for how society understands, conceives and draws from nature.

In 1966, Stevens presented his _Walking on Water _series, which comprised a variety of playfully inventive works presented throughout Battersea Park in London. Among these were inflated spheres that participants could climb inside — floating atop bodies of water, walking along the inside surface, a little like a rat in a spinning wheel. Other works included Atmospheric Raft 1969, an inflatable pontoon or ‘pontube’, and Overland, Overwater, Airborne, Submarine Transport System 1971, an inflated tube lying across a variety of terrains for participants to traverse. These works were not just extensions of the body but experimentations and opportunities for participants to extend themselves, and, for a moment, feel as if they were superhuman within a widened perceptual field.

Thirty years later, in the corner of the Kinetica Art Fair, the documentation of these works is the only existing format in which they live — the works themselves were destroyed in a fire in the late 1990s. The details of the fire are complicated and unresolved; Stevens claims that his private property and artworks were destroyed in a fire that was instigated by the British government and has since embarked on a lengthy court case to dispute their actions. In light of this, Stevens suggests that his career has moved from material sculpture to conceptual work, and has exhibited the films alongside a new triptych titled, Now History Repeats Itself [1965–2012] 2012.5 This final work consists of three framed certificates, two of which provide the details of Atmosfields and Desertcloud, and the final frame explaining his ongoing court case over the fire that destroyed the works. In this work, Stevens draws parallels between himself and other artists in the past who have had their works destroyed for a variety of social and political reasons and in this light, the cycles of art history are constant and inevitable.

Stevens’ investigations were not only social and political, they highlighted ecological concerns. At Kinetica, he introduced his films as ‘the first films on global warming’:6 artistic experimentations that negotiate the changing relationships between society and nature that had the potential to develop solutions for environmental design. These issues are as common today as they were when Atmosfields and Desertclouds were initially constructed, although perhaps in a more urgent manner. As Timothy Morton has argued in The Ecological Thought, contemporary society increasingly has to recognise the existence of hyperobjects — things that are real, evasive and also persistent, such as global warming:

Unlike snow, you can’t see it or touch it; this gives global warming deniers a foot in the door. But the kicker is, it’s much more real, in a very precise sense, than a snow shower. It’s the snowfall that becomes the abstraction!7

Similarly, Stevens and his contemporaries were not just intrigued by futurology, but by materialising how anxieties around the future can be manifested, even when the future is itself, inevitably unpredictable. Stevens was creating representations of the future to ebb anxieties, while making peace with the fact that we don’t know what the future looks like.

In the past, Stevens’ participatory inflatable pneumatics were a way of preparing for the future, much in the vein that Buckminster Fuller did in the 1960s — for contemporary audiences, these works now take a new turn. Experimenting with the processes and transformation of natural resources becomes less about breaking down traditional codes of representation and more about engaging utility-based environmental design with alternative viewpoints. Although utopian, the concept and implications of hyperobjects perhaps results in a desire to materialise social issues. Stevens’ films of his pneumatic works not only attempt to make visible the imperceptible processes of energy in transformation, they also explore the way in which these transformations form and move. This kind of kinesis produces a new materiality emergent through the study of natural systems, a relevant and affective means for harnessing and expressing contemporary anxieties that surround environmental issues.

Christina Chau is a PhD student at the School of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia.