As its title suggests, Occasional Miracles: Contemporary artists respond to the Shepparton Art Museum ceramics collection makes use of a classic curatorial device by inviting six artists to create new works that engage with the museum’s extensive holdings of historic Australian and international ceramics. It seems a foolproof formula. The museum’s collection is enlivened with a contemporary charge while, in return, participating artists are bestowed with a ready-made muse and institutional support to realise a fresh body of work. Yet, in truth, such exhibitions entail a rather tricky balancing act. They risk the collection being glibly shoe-horned into the overarching logic of the artist’s broader practice or, worse still, the artist being so beholden to the original artefact that they end up producing incredibly boring art. What is miraculous about the exhibition presented at SAM is that these pitfalls are stealthily circumnavigated and we are instead offered a series of intriguing works that maintain the integrity of both their source material and the artists’ practices. This truly is a wondrous thing.

Jacob Ogden Smith’s Ginger Beer Bottles with Assorted Accessories (2013) and Rebecca Baumann’s Untitled Field View (2013) embody opposing responses to the exhibition’s proposition. Ogden Smith’s jumbled grouping of nineteenth century ceramics bottles and flasks, clunky contemporary ceramics, soda bottles, packaging and a home brew kit sprawls across two tables at the centre of the gallery, while Baumann presents a sleek installation of monochrome ceramics displayed within precisely placed vitrines and paired with a formation of coloured squares that wrap neatly around a corner of the space. Beyond the striking aesthetic contrast lies a more fundamental difference in the ways the artists approach their subject. Ogden Smith expands on the embedded social and functional context of the beer bottles, demijohns and potato flask with which he worked. Home brew is the work’s activating agent—the artist held workshops on how to harvest wild yeast for its production, enlisted locals to tend to six ‘ginger beer plants’ in the lead up to the exhibition and then dispensed the resulting beverage at its opening. Ogden Smith also produced a number of ceramic bottles inspired by the historic potato flask. Their bulbous forms are reminiscent of a ginger root but could equally stand as an icon of the rhizomic structure of the work itself.

Baumann’s installation, on the other hand, is wholly focused on the formal properties of the ceramic vases and dish she utilises. The nine accompanying wall panels rendered in dazzling hues are designed to frame these objects, creating eye popping colour combinations that highlight their luscious glazes and curvaceous forms. Untitled Field View continues Baumann’s ongoing exploration of the affective qualities of colour; however, unlike previous works that utilised simple mechanisms to create shifting colour schemes, this one remains utterly still. One vitrine has even been left vacant, as if time itself were arrested inside its casing. However, as the viewer moves through the space the work becomes activated, colours converge in fluctuating configurations and we are reminded that the flow of time can never be stemmed.

Emma White’s The Plastic Arts series (2011) and Katie Lee’s Collected Objects, Varied Materials (2013) are allied through their meditations on materiality and the process of making. With a long-term interest in still life traditions, White has developed a practice in which she constructs compositions of everyday objects from Femo (polymer clay), then documents and presents them in ways that confuse distinctions between the real and simulation. Her vibrant digital prints and a frenetic stop-motion animation are displayed alongside Gwyn Hanssen Pigott’s Sand still life (1994), an arrangement of highly restrained ceramics from SAM’s holdings. This somewhat jarring union is buttressed by the artists’ shared admiration of the late Italian still life painter Giorgio Morandi. His influence is evident in their common focus on a restricted range of domestic objects, repeated in unending iterations. White and Hanssen Pigott are further linked through their obsessive fascination with the durational and material processes of making. This is most clearly articulated in White’s animation, which depicts a seemingly infinite sequence of formal possibilities produced from a single piece of modelling clay.

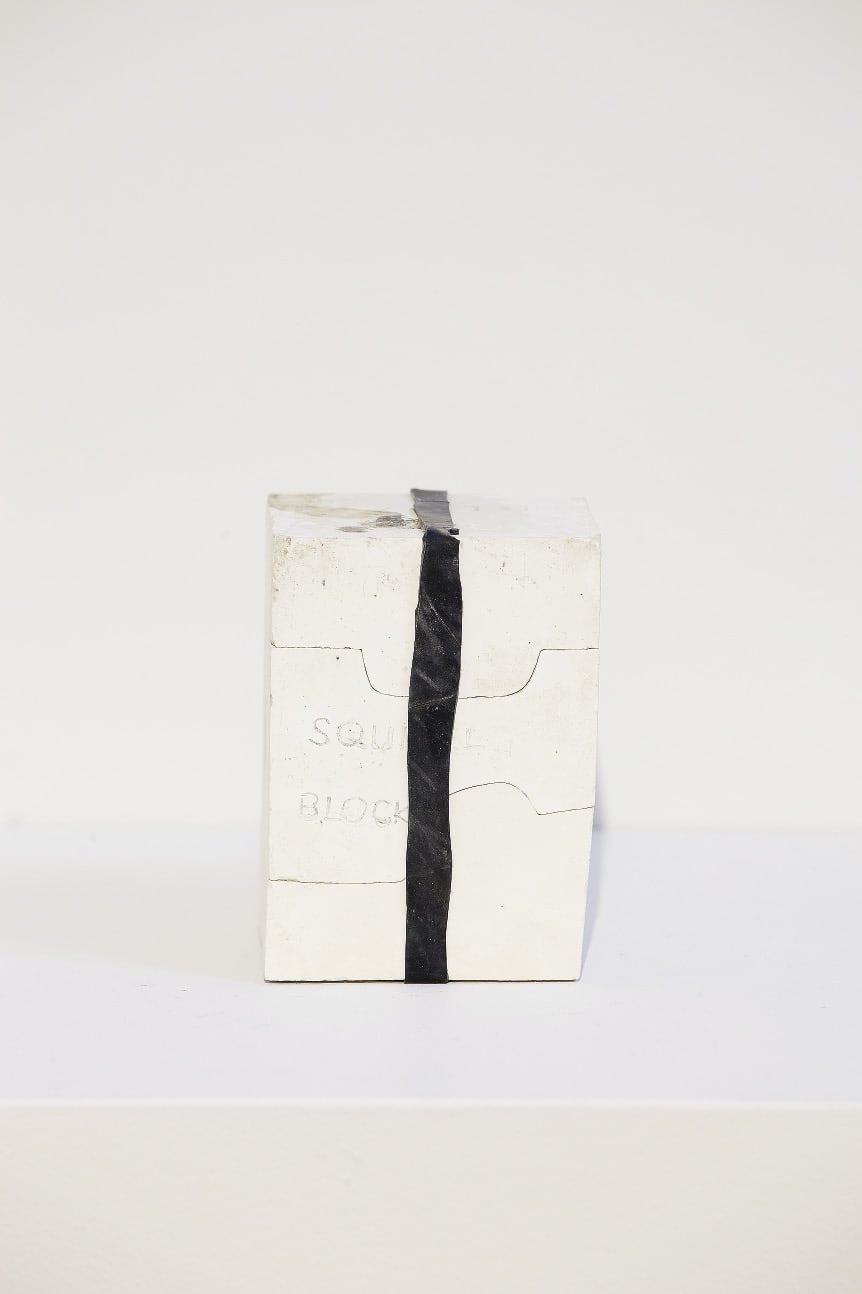

Typically working on an architectural scale, in Collected Objects, Varied Materials Lee presents an assemblage of more modestly sized artefacts on tiered wooden shelves. An assortment of functional ceramics, including an old fashioned foot warmer, pipes and a vase perforated with holes for flower stems, are interspersed with a series of sculptures which the artist has produced in response to their material and formal qualities. Through an intuitive process of translation and reduction, Lee’s newly crafted forms retain a vague impression of utility yet are completely emptied of any practical application. Functionality has been replaced with a tantalising tactility. Featuring many of the artist’s favoured materials, such as rubber, wood and metal, these curious objects cry out to be picked up, held and caressed.

Christopher Hanrahan adopts a more distanced approach to his subject in Museum Suite (pentimento) 1–14 (2013) and in so doing reflects on the broader workings of the museum itself. The suite of black and white prints depicts a series of Darbyshire Pottery plaster moulds used by the now defunct West Australian company to produce ornaments in the 1950s. Hanrahan asked SAM to email him low-resolution photographs of the casts from its database, which he then digitally enlarged and manipulated. The grainy, shadowy quality of the resulting images suggests a haunting absence. The work deftly evokes a sense of melancholy for Australia’s dying manufacturing industries while simultaneously probing the relation between artefact and museum. Safely closeted in SAM’s collection, the casts are immobilised and rendered useless, yet they retain the eternal promise of reactivation. This is what Hanrahan circuitously achieves through a work that implicitly traces the casts’ evolution from functional objects to obsolete relics, precious museum artefacts and, finally, contemporary artworks.

In a satellite project accompanying the main exhibition, Andrew McQualter has produced a temporal work for the museum’s drawing wall. Inspired by the gestural provocations and patterning of objects within the collection, The realised gesture (2013) portrays a series of delicately painted figures engaged in various acts of holding, exchanging or contemplating ceramic vessels. These enigmatic portraits emphasise our bodily and cultural connection to the material world.

Curator Elise Routledge has pulled off an impressive feat in bringing these diverse practices together in an exhibition that is not only spatially and conceptually coherent, but that also enriches both the museum’s collection and the practices of the artists who have engaged with it.

Shelley McSpedden is a Melbourne-based writer and educator.