Post-irony: the beginning

One day, my roommate, who is not an artist, but is still interested in art, asked me to define my art practice. As I later retold our conversation to some art school friends, I noticed how I kept positioning my roommate as someone who is outside the art world, which simultaneously feels accurate and wrong. And I couldn’t explain to myself why I felt it was so necessary to classify him as such. I also was not sure whether this construct was necessary when discussing any other field, in that I believe no one would have to say, for example, ‘My friend, who is not a geologist but enjoys rocks…’ and not even in other fields of culture does this happen, such as, ‘My friend, who is not a musician, but has heard music before’, or, ‘My roommate, who is not a novelist, but reads books on occasion…’ It felt necessary at the time to make that distinction, even though now it seems absurd.

But my roommate, who is not an artist, but is still interested in art, asked me to define my art practice one day. I replied that, if I had to, and I would prefer not to, but if I really had to, I would probably choose a descriptor like post-ironic. It seemed to fit what I was doing at that moment more accurately than any other term or movement I considered. Of course, post-ironic is already a buzzword, ripe for mocking, with its notion that it could be possible to move past opposing stances of ironic distance and sincere feeling. And ever since those words left my mouth, to punish me, and to my dismay, my roommate has taken to describing pretty much everything as being post-ironic. To which I replied that should he continue to insist on labelling everything as such, the term itself would lose all meaning. Post-ironic felt like it could actually mean something, that it could describe the attempt to represent one’s self with at least some degree of truthfulness in an age of overriding sarcasm and posturing, while at the same time recognising the absurdity of such an attempt. I didn’t want to lose track of what its meaning was, similar to how the term’s ancestors, irony and post-modernism, had (arguably) meant something at one point, but as it stands today are pretty floppy and lifeless, as words go.

Our conversation was yet another lesson in how crucial definitions are for artists. Picking the right term to describe your art is the beginning of the conversation about your work. If sending your art out into the world is like sending away your child to fend for itself, priming the conversation with a few carefully chosen terms is like giving your kid a warm jacket and a sandwich for later (and maybe some carrot sticks for a snack). I chose post-ironic in that moment of talking to my roommate because it had more accuracy to it than post-truth, which is also a term that has been bandied about with frequency but which I also find relevant and intriguing. Post-truth here is meant in the sense that Facts, which at one point were classified as being Objectively True, simply aren’t as important anymore as the ability to persuade people into agreeing with whatever it is you agree with. Truth, one time all-star of the Enlightenment, has been fighting and losing a two-front war: one against postmodern and deconstructivist theorists who champion multiple readings and interpretations, and the other against religious fundamentalists who are also in support of the same thing but for other reasons. Post-truth, while also an influence on my work, is not as snug a fit as post-ironic, although the two terms definitely overlap, due to the proximity of the definitions of sincerity to the practical realities of living in a post-truth world.

Lana Del Rey: Why?

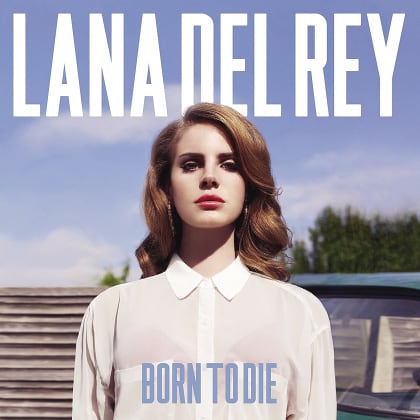

Question: why do I like Lana Del Rey so much? I don’t really know, other than I like listening to her album, Born to Die. I liked that album so much that I listened to it more than any other record or any other artist for the entire year of 2012. And I still listen to it, too. A brief history of her rise and semi-fall: Lana Del Rey released, online, a self-directed music video titled ‘Video Games’. To summarise, the song is Lana singing over maudlin harps about how much she loves her boyfriend and how he’s always playing video games. The music video garnered much attention and was the spark that provided all the initial attention for Lana, who, as the story went, personally edited together a bunch of YouTube clips of skateboarders, old movies, Hollywood icons, fashion models, and shots of herself looking all sad and pouty.

The aesthetic of this video was the aesthetic of Tumblr, where people collect images and videos and songs for themselves based around a specific idea of what images are attractive and desirable (for a certain set, this means old school glamour, anything vintage, and anything with a warm, 1960s colour cast). This aesthetic—although it requires no creative input (meant in the sense of creating things, like artwork, music, or text) on the part of the Tumblr user, aside from accumulating what’s deemed relevant—is very tightly wound up in the specific Tumblr user’s identity, personality, and most importantly, individuality. And the idea that a lone songstress, sitting alone in her bedroom with her laptop, could take this aesthetic and make such a coherent homage to everything this group of teens and 20-somethings cherished as beautiful and special was lauded as a triumphant validation of that aesthetic. Lana Del Rey was a hero to the youths.

But then, because it’s the internet, there was a backlash. It was revealed that before her present incarnation, Lana Del Rey had taken a stab at a musical career under her real-ish name, Lizzy Grant. It was also revealed that Lana Del Rey’s father was a wealthy domain name investor, and that at some point either before or after her first unsuccessful attempt at an album, Lana consulted some musical consultants who advised her on name changes and who knows what else. When people started to collect and put these pieces of disparate information together, a narrative sprung up that maybe Lana wasn’t as grassroots as had previously been assumed by random people on the internet. People feigned outrage, or possibly were outraged (it’s always difficult to tell online) that someone who seemed independently creative actually wasn’t as much. It was offensive to the community that she could have been so calculating in her appropriation of an aesthetic that so many people had been working so hard to assemble together for free, purely for their own non-monetary enjoyment.

The backlash against Lana was intense. Prime-time media coverage was devoted to her Saturday Night Live performance, both because of her bombing it and the reactions that other questionably famous people had to her bombing it. The nights following her SNL debut, she was probably treated to more coverage than actual, literal bombings. As is often necessary in our society, it was important to a lot of people that she fail publicly, because a lot of people had invested a lot of emotional energy into the idea that Lana Del Rey had somehow snuck her way into the special authentic artist club through the backdoor, and now the cultural bouncers were asking her to leave.

Sincerity ≠ Reality

The victory of belief over fact is a victory of a particular type of sincerity, because, similarly to how being American means you have the right to not learn all of the facts of a situation before forming an opinion, being sincere indicates a feeling inside of you, irrespective of reality, where all that is required is that you believe in something strongly enough. Sincerity means a belief inside of you, that you wish to see manifested outside of yourself, in the world at large.

With sincerity comes moral implication. To live for something you don’t believe in, or to not believe in anything, which describes the life of the cynic, carries with it a criticism and judgment that you’re living the wrong way. This is the life of the ironic persona as described by people who actively consider themselves sincere. This is why, in the US, more people would vote for a Muslim president than an atheist president (no facts were researched to support this statistic, but it feels like something that would be true). On the flipside, dedicating your life to living up to your and to society’s ideals, and living for what you believe in, seems to be, morally, the most correct thing to do. This is according to the entire collection of American mainstream culture, in which the lesson seems most often to be Work Hard, Respect Others, and Be True to Yourself.

I Am… Sasha Fierce

As a musician, as an artist, as a cultural creator, as an internet commentator, if you plan on living the life of a persona, you can’t continually tell everyone that it’s a persona, because that defeats the purpose. There are a group of performers who thought, or their marketing teams thought, that they needed to create on-stage personas. Beyoncé became Sasha Fierce with her 2008 album, a persona whom she described as being the more outgoing, fun-loving, aggressive/assertive side of her, the persona she inhabited when she stepped on stage. The album, although blessing the world with the song ‘Single Ladies’, received mixed reviews.

Garth Brooks dominated both the country music and popular music scene in the ’90s, and could literally sell hundreds of thousands of units the day his albums were released. This bothered him, because he couldn’t separate himself, musician and artist Garth Brooks, from music superstar Garth Brooks. Garth Brooks decided to become Chris Gaines, but no one cared, and insisted on not caring very emphatically.

Stephen King, after his immense fame and the same troubled thoughts as Brooks, tried to sell his novels under a pseudonym. King found out that he couldn’t get anyone to pay attention to them. He re-released the same novels under his actual name, and his legions of fans flocked to the titles. These attempts at persona creation can all more or less be considered failures, since they failed to capture the attention of the public. The persona creation attempts received more attention than the culture created under the assumed personas.

‘Curating’

One review I read about Born to Die (on the website Grantland.com) which was influential in helping me crystallise my thoughts about the album and Lana Del Rey’s overall cultural reception compared the songs’ musical compositions to Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks score. As the review stated, Lana’s producers, echoing Badalamenti, were able to craft a minimal, vintage sound by sprinkling in a sparse amount of bass notes here and there.

Keeping in mind the way culture is collected and passed around online, and combining that with the hefty (by blog standards) amount of criticism this culture creation/curation has received, raises a question. At what point does the appropriation and straight up mimicry of past eras by those of the current era become the defining characteristic of the current era? Which brings up another question, which is: what, exactly, is wrong with that?

A lot of hand-wringing has been done about the staleness and lifelessness of our contemporary culture. The critics who are able to get past the hand-wringing and the never-to-be-broken cycle of the older generation shaking its collective fist at the wantonness and laziness of the younger generation are able to make the assertion that artists today have no respect for originality, also pointing out that the only movies that come out are sequels, and that bands don’t sound like they came from the 2010s, because they’re too busy sounding like they came from the 1970s or ’80s.

When the noticeably retro bass plunks and the lean synthesiser treatments of the ’80s get placed over top and combined with contemporary hip hop beats, like the now-standard jittery faux-reggaeton cymbal taps and the ubiquitous, wobbly dubstep bass lines from our current era, it’s my feeling that we of the current generation are then allowed to say that we’ve halted the nostalgic longing for the past and have created something that is specific and unique—at least, so far as culture can ever be that. The current sound, look and style of contemporary culture inevitably becomes a marker that identifies our current era, no matter what era the inspiration has been drawn from. The current generation is capable of blending the past and the present just like any other era has done, and complaining about Instagram, Tumblr and the obsession with our parents’ obsolete technology can’t obscure the creative innovations that keep occurring every year. If a remix of a remix equals the original song, maybe retro plus retro can equal original culture.

Sincerity: it’s not all bad(?)

If you were to poll a group of artists, I’m willing to bet they would tell you that creating art with the utmost sincerity can actually happen. So let’s entertain the idea that sincerity is the starting point for every artist. The issue is not with how it starts, but rather what happens to the art on the other side, after the act of creation for that particular piece has ceased. How can the artist explain the emotional, heartfelt discovery they just unearthed deep inside to other people without sounding cheesy and totally unbelievable at the same time? Trying to explain how much emotion you felt as an artist in the creation of a piece, and then getting that other person to feel that emotion with the same amount of intensity, is incredibly difficult and will ultimately result in mixed signals and misunderstanding. Artists have it rough, but they’re given a lot of leeway at the same time. No one would ever go to a restaurant to have a chef merely describe what the food tastes like, but for some reason people are content to go to movies and museums to have emotions imperfectly described to them.

First first

Lana Del Rey’s first first album, which is not Born to Die, which is her second first album, was released under her real-ish name, Lizzy Grant. It already contained many of the hints of her future follow-up attempt. The title alone, ‘Lizzy Grant AKA Lana Del Rey,’ clearly indicated a desire for persona creation. And yet, despite Lizzy Grant telling us that she was going to be playing the part of Lana Del Rey, the persona is still effective. It’s effective because it’s hard to tell what Lana Del Rey, the persona, is saying, and what Lana Del Rey, the actual human being person, is saying. In ‘Video Games’, Lana repeatedly coos that everything she does, she does out of love for her boyfriend, and that, to directly quote the song, ‘This is my idea of fun / Playing video games’.

There’s at least three layers of mystery here, possibly more. Does her persona actually think playing video games is fun? Is her persona just saying that she thinks video games are fun because she loves her boyfriend and that’s what he thinks is fun? Is Lana Del Rey the actual singer standing in solidarity with her persona in this scenario, is she offering a criticism, is she just telling a story? Or is it none, or all of the above?

To paraphrase Žižek, there will always be a tension between what we want, and what we think we should want. This is why people will both still watch The Bachelor and still read Middlemarch, and possibly feel uncomfortable about wanting or having to do both. All of us are uncertain about what we want, and so it becomes comforting to trick ourselves via cultural tropes into feeling secure within our emotional confusion. However, that’s also the biggest benefit that pretending affords us. We, both the famous and the anonymous, can use persona creation to fool ourselves or fool others, but we can also use it to pretend in an aspirational sense. Pretending allows us to take risks, and gives us a chance to live up to an ideal we wish we could hold ourselves to, even if it’s only momentarily.

The Fly

In 1992, U2 was super popular, super earnest and super heartfelt. In 1992, Bono wanted U2 to be different. To make U2 seem edgier and darker, Bono assumed the character of The Fly, who he portrayed on stage during U2’s worldwide Zoo TV Tour. Bono dyed his hair black, wore dark wrap-around sunglasses, and dressed all in leather. The Fly was an egomaniacal rockstar, darker and more aggressive than the nice bright-eyed boy Bono used to be in the 1980s, but possibly a pretty accurate summary of how Bono is today. Bono even took to remaining in character away from the stage.

Bono wanted to be The Fly so that he could say things that Bono couldn’t get away with, but he told people this point blank. Exactly like how telling someone you are performing as a persona ruins the persona, Bono undercut the purpose of The Fly. If you tell people you are creating a persona to say things you couldn’t otherwise, they’re still going to know that it’s you saying it. Presumably, if you catch heat for saying it, it’s actually the Real You you that’s going to catch heat for it.

Once the Zoo TV Tour hit Europe, U2 felt they could not perform while ignoring the violence happening in Sarajevo. A plan was conceived to have a live satellite hook-up during the concert with citizens living in Sarajevo. At the time, Sarajevo was under an oppressive siege, leaving many people in the city without electricity or running water. In order to broadcast their concerts to Sarajevo, U2 had to apply to the European Union’s broadcasting licensing bureau, and the band purchased a $100,000 broadcaster’s license, essentially turning U2 into a legally sanctioned television station. During short breaks in U2’s musical performance, Sarajevans could communicate with Bono and Bono with them. Speaking about the live broadcasts, guitarist The Edge, who seriously has people call him The Edge, said, ‘A lot of nights it felt like quite an abrupt interruption that was probably not particularly welcomed by a lot of people in the audience. You were grabbed out of a rock concert and given a really strong dose of reality and it was quite hard sometimes to get back to something as frivolous as a show, having watched five or ten minutes of real human suffering.’ The Edge is completely right and completely wrong about this.

Feelings

Trying to explain the feeling behind a piece of art to an outside observer requires constructing a narrative, unless you are extremely skilled at interpretive dance. The narrative may come close to approximating the experience, but ultimately is a barrier to others accessing that experience. Telling a story about feeling an emotion is like listening to your voice on a tape recorder and thinking you sound weird and awful. How many times, if you are an artist, have you tried to explain your work to another person when your mouth starts saying things that you didn’t really mean, even though you didn’t intend to make something up, even though you planned on saying something you really meant, and it was about something that meant so much that you needed to make art about it? Confessing to a preconceived earnestness or sincerity, like a premeditated sincerity, indicates a consciousness of what one is doing and how one is acting.

To do so is an admission that one is performing the role of Sincere Heartfelt Artist. Unfortunate, maybe, and perhaps also unavoidable for people who truly want to be sincere. People who persevere in the task of explaining their art eventually and inevitably have to acknowledge the inadequacy of words for expressing how we truly feel. To invoke Žižek one last time, the story we tell ourselves about ourselves in order to account for what we are doing is fundamentally a lie. That’s actually entirely acceptable, because having both undergone and witnessed the experience of someone talking about their art and not even really meaning what they were talking about, even though in retrospect it seemed like lying, it doesn’t even come close to carrying the weight of the moral culpability of lying. At that moment, the artist was expressing a thought about their work in the only way they knew how: by expressing how they were currently feeling about an emotion that they had one point felt at some point in the past. Which is an incredibly difficult feat.

In conclusion

In conclusion, Slim Jim is a brand of meat jerky snacks manufactured by ConAgra Foods. Slim Jims are popular, and over 500 million are produced per year in the US. Slim Jims used to be advertised by a man named Macho Man Randy Savage, who also used to be a professional wrestler. Macho Man Randy Savage is now none of those things, because he died. On the morning of 20 May, 2011, Macho Man Randy Savage died after having an enormous heart attack while driving around with his wife in Florida. He was 58 years old. It was initially thought that the cause of death was due to Macho Man Randy Savage losing control of his car and slamming into a tree by the side of the road. Autopsy reports later revealed that Macho Man Randy Savage had an enlarged heart and a very advanced case of coronary disease. All indications are that Macho Man Randy Savage was unaware of his condition. His wife survived the accident without major injury.

In 2009, there was an explosion at the Slim Jim manufacturing plant in the town of Garner, North Carolina, injuring 38 people and killing two. Production of Slim Jims were halted and a new facility was opened in Troy, Ohio. The Garner facility was brought back online, but eventually was permanently shut down on the morning of 20 May, 2011, the very same day that Macho Man Randy Savage died.

This is all sad, because, in 2009, people died while working to make Slim Jims, and then, in 2011, another much more famous person died and will always be remembered because of Slim Jims. And also a lot of people lost their jobs in a town that only has 25,000 people in it, and it must have been somewhat of a blow to their local economy in which the median annual income is $43,000. Furthermore, someone, somewhere noticed that the North Carolina plant closed on the same day that Macho Man Randy Savage died, and then wrote a single sentence about that and left it on Wikipedia.

In conclusion, there is so much information in the world that no one really knows for sure what to do with it. I’m not sure that this has ever been a problem before in the history of knowledge. There is so much information that up to a certain point, all anyone can really do is to point at it and say look, look at this thing that happened. What happens when we have an instance where two things happened at the same time? Two things are happening all the time, and often in greater frequency and number than just two at a time. Things seem connected, but they probably aren’t, although we can’t really say for sure one way or the other. The rise of postmodernism and the end of modernism. The death of irony after 9/11. The death of irony after Obama’s presidential election. The rise of vintage and the end of culture. People try to make these connections, most of the time they fail, and sometimes they look silly doing it. But people keep trying, and that’s the most important thing that we can all do. The thing that makes things interesting is if no one can really say for sure.

Tim McCool is a native of Pittsburgh, PA. He is a recent graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.