I feel I’m in a beautiful private garden, in the middle of the city. I look up and see all the buildings and the beautiful sculptures. On Tuesdays, when the gallery is closed, it really does become our private space. It’s that sense of privacy in a public environment that I enjoy.1

—Isobel Crombie

Throughout the latter part of 2012 and precipitating in February of this year, the public of Victoria came to know of something imminent and unprecedented—the forthcoming Melbourne Now ‘summer event’ soon to engulf the National Gallery of Victoria in late November of 2012. Since day one of his appointment as director of the NGV, Tony Ellwood has been hustling with hyperbolic phrases like ‘daring and revolutionary’ and ‘new methodology, ambition and scale’, effortlessly breezing about from café to garden to press club to desk, posing with coffee cups, newspapers, and solemn meaningful gazes, all to promote this upcoming exhibition and the recently passed series of ‘forums’. This constant hustling has now, in May, reached somewhat of a statistical climax as we are now assured Melbourne Now will be the largest exhibition ever mounted by the NGV, with over 8000 square metres of space and a minimum of 125 artists.2

As the title suggests, Melbourne Now will apparently showcase and give evidence of the transdisciplinary dynamism occurring ‘now’, right in this moment, right as you read this, in Melbourne, across art, design, fashion, film, dance and architecture. Furthermore this utmost of contemporary of exhibitions will be a tandem operation, marking a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way the NGV will operate. Gone are the days of the ‘moribund’ gallery. Now, in a gesture of direct democracy and horizontal structure, the institution is seeking to ‘let go of some of the control’, calling upon the public to ‘collaborate’ with them, and ‘participate’ in the ‘conversation’.3

It is from this speculative perspective that we endeavour to take up our dubious position as reviewers, intuiting the exhibition before it has occurred, and navigating the heavily mediated space between the unknown and the corporate rhetoric that has so far come to define Melbourne Now.

The participation campaign began early in February of 2013, when every Sunday various Melbourne creative practitioners and NGV staff held a ‘forum’. On the stage of the NGV Clemenger Auditorium, a loose discussion, mediated by a Radio National personality, bounced between the individual and the broad topic of the week. The month started with Collaboration and ended with Melbourne Next. The structure of the two-hour event, simulcast on Radio National and streamed online, emphasised the handpicked speakers, with relatively small question time for the audience—the overt presence of microphones and video cameras making any participant acutely aware that the spectacle was being watched and recorded, as well as archived and transmitted beyond the here and now.4

This pursuit of participation as signifier of the now, in its seductive innocence, is simultaneously and inherently fraught. Beyond the veneer of a supposedly collaborative dialogue, a far more tactical and manipulative institutional manoeuvre can be recovered. In The Nightmare of Participation, Markus Miessen posits that participation has become a radical chic, ‘a mode of buoyancy production, a societal sedative’ which withdraws ‘the ground from which they [the populous] can actively critique the actions of the decision-maker’.5 Thus, in this context, institutions abdicate their position of criticality and rather present participatory methods such as criticality itself, therefore exchanging responsibility for marketability in their struggle for maintaining power and administering cultural capital.

What prevails is a suffocating consensus, which, in the case of the NGV, has morphed from an in-house treadmill dictated by closed-circle power, to a consumer-driven merry-go-round dictated by collaborative and horizontal structures. Symptomatic of this is that the public is rendered homogenous—it doesn’t matter who participates but rather that one participates and becomes complicit in a complex of structural indifference.6

Through this lens, the Melbourne Now forums come to legitimate and extend this tactic. ‘Participation’ is equated to a carefully nominated and representative ‘artistic community’ who then perform on a stage under the NGV brand—the reason for their being there remains as unknown as the exhibition they were supposedly there to talk about. The context for collaborative discussion is then further drowned by networks of complicity, especially when examining who made up this in-group. The most forthright of these selections was Susan Cohn, whose also sits on the NGV Council of Trustees, and has been curated into two of the more recent and major exhibitions on Australian art at the gallery, Negotiating this world and Mix Tape 1980s. To a lesser extent, the positions of Ash Keating, Jon Campbell and Susan Dimasi on their forums are problematised by the recent acquisition, facilitation and collection of their work by the National Gallery respectively.7

What is not important here is what these panelists said or whether or not they managed to maintain a semblance of criticality or autonomy. What matters is that their participation become illustrative of the institution’s apparent desire to fortify consensus and liquidate ‘collaborative dialogue’ into symbolic capital and marketing opportunity, and ‘creative practitioners’ into spokespersons. This is extended in the case of Melissa Loughnan—who was the only gallerist to publically put her name to criticism of the NGV under its previous directorship, and also the only gallerist selected on the panel. Her rebranding then comes to associate the aforementioned desire of the institution for consensus with a more devious and concerted attempt to pacify any adversaries.

This matter is compounded but also explained through a consideration of how these forums were structured, as well as how they, in turn, structured the knowledge they produced. In Privacy + Dialect = Capital, writer and curator Clementine Deliss considers a kind of knowledge that actively resists and rejects involvement with conventional modes of information. This is a knowledge that is highly ephemeral and difficult to control, often circulated covertly and informally among a limited audience that is well-versed in the ‘dialects’ and methodologies that characterise it.

Thus the Melbourne Now forums come to exemplify these networks of dubious knowledge—operating only for those already versed in the vocabulary. In this way, the forums broadcasted on Radio National and simulcasted online can be flattened down to marketing advertisements for a select audience. Thus the creativity of these forums did not lie in good-natured discussion supposedly helping Melbourne Now to know itself, but rather it found the skillful differentiation by the curators to capitalise on the missed gap of the virtual (the marketing radio transmission, the forum), becoming actual (becoming realised, its own actualisation). As Deleuze emphasises, ‘the actual does not resemble the virtuality that it embodies’. Here, the forums of propaganda do not match the marketing message.8

These speculative networks of dubious knowledge then flow on from the forums to engulf the exhibition itself. For example, Melbourne Now, in its unrealised, quasi-mythic state, can only be understood as ‘symptom’ or as an ‘inadvertant non-sign’, constituted by the non or repressed knowledge uncomfortably and discretely wedged between what is known and unknown by the institution and public. Moreover the exhibition becomes a site that produces this symptomatic knowledge, which by definition is unintentional, uncontrollable, unproductive and a by-product of something else. How we as a public are not to know anything, but are left to speculate over the elaborate marketing, in submission to a covert class of those who know. By employing a cohort of public figures embroiled socially, professionally and financially by the daily operations of the NGV, two interlocking issues emerge: the first is that the NGV has left the audience without a substantial framework or criteria for their selection, as was the case in the forums and is the case in the exhibition. While certainly convenient, this further promotes the production of dubious and speculative knowledge in relation to the effects of power and subjectification that naturally come to encircle interiorities. Through this rhetorical participation we are now able to understand that Melbourne Now, and indeed any public or critical intentions, all have their own agendas, their own unconscious on top of their own unknown knowns.

Ultimately what we are left with is an institution desiring/needing to redefine itself as relevant, with a social utility necessarily measurable and interlinked with other industries and institutions, like that of the free market. Following the success of a drastic increase in attendance numbers at GOMA in Brisbane, where Ellwood was formerly director, the NGV is prescribing to the neoliberal demand for an ever expanding modality to deliver and transmit marketable artwork and content—otherwise known as the flailing upkeep of being ‘here and now and present’ enforced by the market’s demand for the lateral expansion of industry. This is reflected not only in the institution’s new and emphatic focus on the ‘now’ but also in the overarching message of a ‘mixed-lolly-bag-hegemony’ of intentionality and of clear outcomes for both institution and community.

So, we find ourselves lost in a trendy, pluralist, ‘happy-mix’ wash—this increasing expansion approaching and leaving us, right now, not participating, but rather swirling and washing around in the corporate, trained dialogues of only those ordained, their voices electrified by a pronounced newness masquerading as substance. But is it really that new?

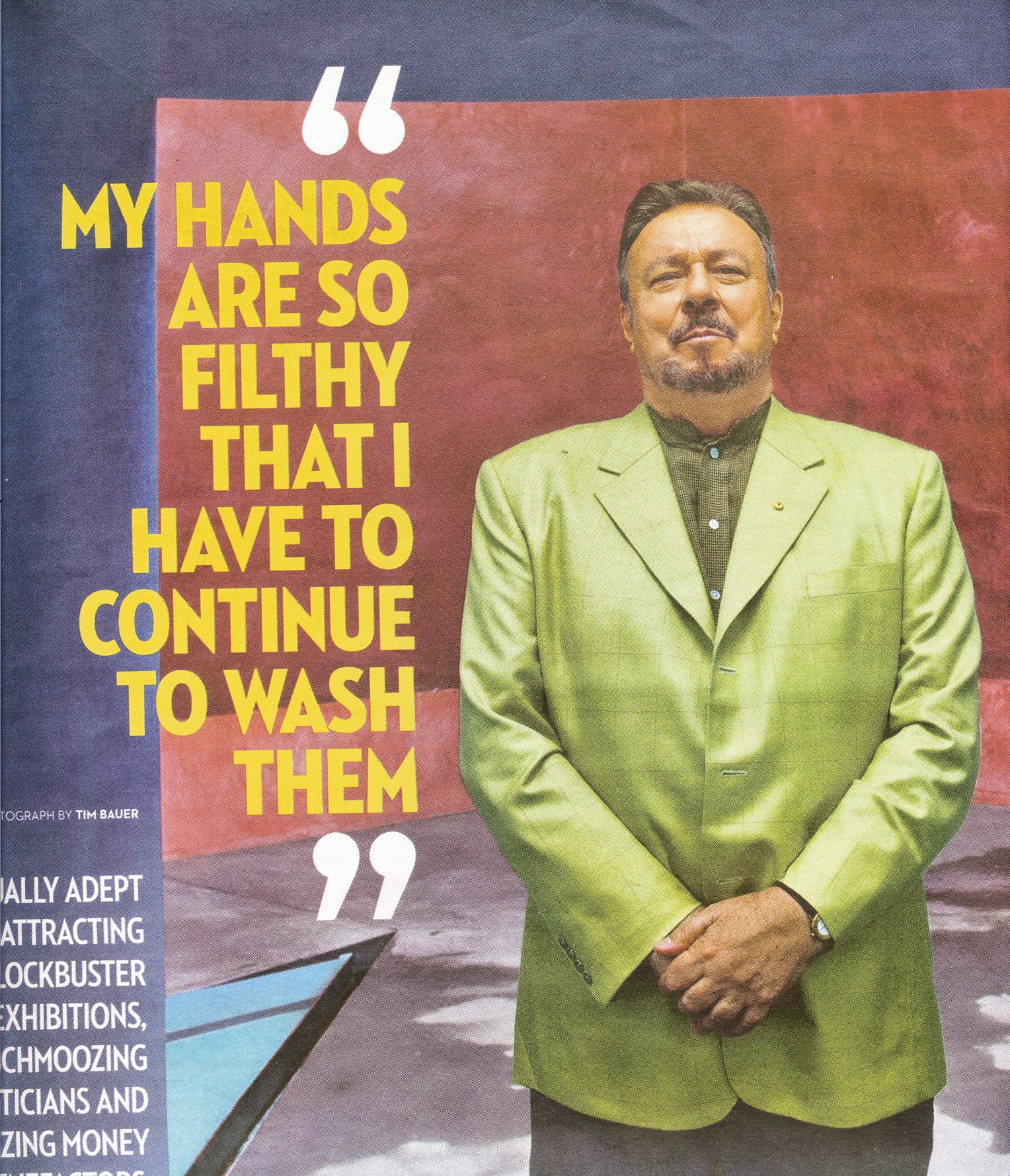

In a moment of confluence, on 16 February 2013 in the middle of the forums, the director of the National Gallery of Australia, Ron Radford, brazenly declared himself a whore.9 Published in the Good Weekend magazine, the article by Jacqueline Maley describes Radford as ‘a getter-of-money, a beggar for donations, a schmoozer of politicians’. The gallery director here is a duplicity—a whore and a hustler—manipulating and extracting money from governments and patrons, which the hustled public will in turn show due gratitude for, thus increasing visitor numbers and generating profit. This, then, engenders a similar public who demand a certain standard of blockbusting quality on a consistent basis, rewarding or depriving their directors with measurable forms of ‘success’—attendance records, tickets and merchandise sales, website hits, etc. But that public is also willfully exploited and satiated through increasingly elaborate and competitive marketing strategies to ensure the attainment of these measurable forms of success. In this system, and as exemplified by the upcoming Turner show at the NGA, there is no ambiguity, nor criticality or even conflict. The museum hustles and whores for a show they know the public will attend and thus affirm—Radford, on record, expects that this show will break the attendance records set by the previous exhibition of Turner at the NGA held in 1996.

Returning to Melbourne Now, it would seem that the gloss on the words ‘participation’ and ‘collaboration’ would have you believe that the whore’s hustler and the hustler’s whore have been banished—victims to the paradigm shift and a new institutional rigour. But, perhaps in acknowledgement of this artifice, Tony Ellwood in his first significant public speech, came to the defence of marketing—that, at their assertive heart, marketing campaigns have ‘outreach and audience development’—they give the philistine a chance.10 But when the supposed content and methodology of an exhibition dissolves into marketing, it seems we have a problem at the heart of the institution—a problem we know all too well. The hustler and the whore, with additional smoke and mirrors. A problem that participation cannot fix.

Aodan Madden is an artist and writer. Beth Rose Caird is an emerging artist and writer based in Melbourne.