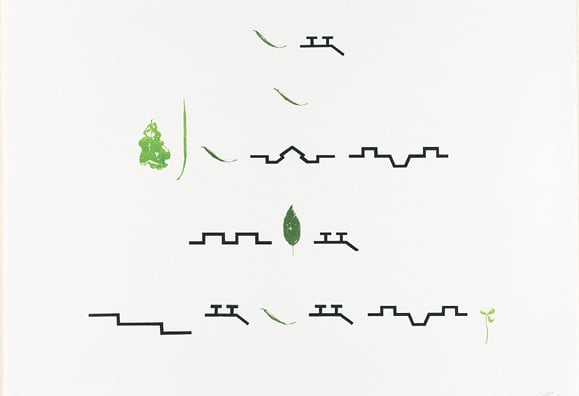

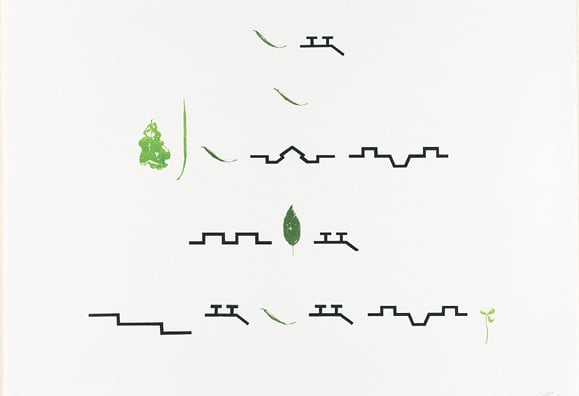

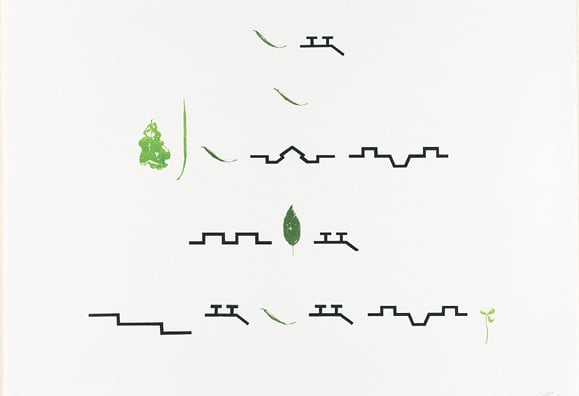

Sriwhana Spong, At a place not stated 2014. Lithograph and screen print. Courtesy the artist and the Australian War Memorial

Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio

Sriwhana Spong, At a place not stated 2014. Lithograph and screen print. Courtesy the artist and the Australian War Memorial

Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio

Parliament House, Canberra

17 March – 5 June 2016

Each year, out of the darkness and Canberra’s Autumnal pre-dawn chill, tens of thousands of people come together, huddling on temporary aluminium bleachers, to be a part of the Australian War Memorial’s Anzac Day Dawn Service. The ceremony takes the armed services as its centrepiece. It focuses on tragic loss, ‘They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old’, and commits us to a penitential duty, ‘Lest we forget’.

Lest we forget.

What kind of a commitment is it that we make as a nation when we send our forces to war? And what gesture are we making when we agree to bring the country to a shared pause, on one particular day each year, to reflect on this commitment?

A considerable amount of work has been done to entrench this tradition. Over the years that span the Centenary of World War I, Australia will have spent $83.5 million on commemorative activities. The figure marks the political importance of the enterprise, but it also registers the strain of keeping these collective rituals relevant. Fewer and fewer of us have a clear and shared sense of what the Anzac tradition should or could stand for. This is not a problem to be solved, it is simply a fact.

In a curious, modest way, the Centenary Print Portfolio, an Australian War Memorial commission, both acknowledges that fact and instigates a suite of experimental responses to the problem of maintaining a shared commemorative tradition. While the artists implicitly test the symbolic currency of our Anzac traditions, none were inclined to refurbish them. Instead, they sought out the kind of commemorative gestures that better suit our actual relationship to our Anzac history. The Centenary Print Portfolio doesn’t aim to refresh the national story of the Anzacs, it demonstrates the work that is involved in curating history and cultivating a meaningful response to it.

So then, what kind of work is being done in Sriwhana Spong’s sparse, assured and cryptic version of the Anzac story?

At a place not stated (2015), is a cool and rigorous work which admits the difficulties of meaningful response across the gap of a century. It distils the worst of trench warfare into a schema that registers nature’s obliviousness and resilience, and shows the marks of planning and strategy as obstacles and epitaph. Spong’s work succeeds in expressing the problematic relationship most Australians have with Anzac rituals. It shows how commemorative gestures have to be sought out and worked up, contrived again and again. If these gestures are to have meaning, it will be the meaning we have invested in them.

The portfolio had its first public showing at Parliament House. It spent a quiet few months in the public gallery, proposing a problem in a place that doesn’t embrace ambivalence. Along with the Anzac Community grants — small parcels of money provided to community projects commemorating the Centenary — this project provides a vernacular alternative to our formal ceremonies of remembrance. And that is sorely needed.

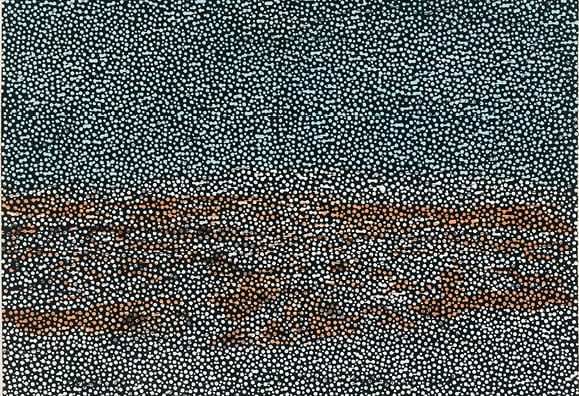

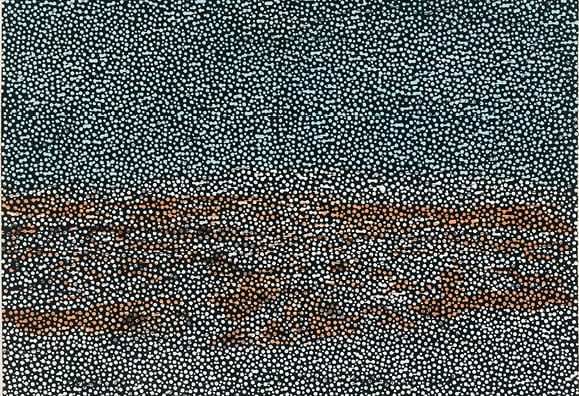

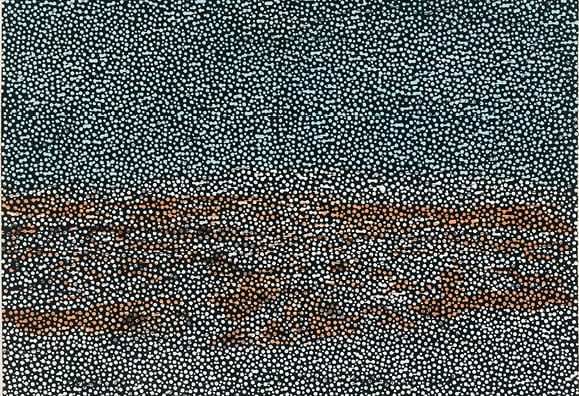

Daniel Boyd, Untitled 2014. Lithograph and woodcut. Courtesy the artist and the Australian War Memorial

Daniel Boyd, Untitled 2014. Lithograph and woodcut. Courtesy the artist and the Australian War Memorial

Anxiety about the possibility of historical honesty runs through many of the portfolio pieces. Daniel Boyd’s lithograph,

Untitled (2015), gives the clearest example of how this anxiety has shaped the collection. The work layers and then filters a sequence of associations. Boyd researched his grandfather’s service in the Memorial’s archives and found details about where he’d fought. He registers this connection through landscapes of that area, sketched by the war artist Otho Hewett. Boyd places an inverted dot-painting filter over one of Hewett’s panoramic landscapes — resulting in a series of holes or lenses through which the landscape can be seen. The work speaks of the many valid vantages from which people render versions of history. The overlaid filter gives the landscape the surface aesthetic of Indigenous dot painting and pays homage to the Indigenous Anzacs, like Boyd’s grandfather, who contributed to the Anzac tradition.

Brett Graham shapes his Anzac commentary,

Bury my patu (2015), from a peripheral detail of Maori tribal politics and the latent pathos of a machine-gun shredded knot of barbed wire. A tangled line folds back on itself repeatedly, forming a complex knot at the centre of the work, contained by a thin border of text. Graham’s work revives the story of the Waikato tribe’s conscientious objection to the war. Maori had initially been excluded from the New Zealand forces but Maori politicians, from tribes seeking assimilation and citizenship, petitioned successfully for their people to be allowed to fight. The Waikato were not so eager to contribute to the war. They refused the call up and went to prison instead. The text that borders the barbed wire scrawl is a Maori, English and Turkish rendition of King Tawhiao’s rejection of New Zealand’s role in the war. It concludes: ‘Waikato, lay down. Do not allow blood to flow from this time on.’ This symbol of the warped energies of wartime ingenuity, cordoned off by the stirring rejections of war, has an emblematic quality. It insists on telling a rival version of New Zealand’s participation in the war, while celebrating the same staunchness of purpose and resilience typically associated with the New Zealand Anzacs.

The portfolio demonstrates a clear aversion to the iconic signs and symbols of Anzac. The artists instead offer up conceptual composites, allegorical juxtapositions and textual conceits. The one work that does engage directly with the iconography and the rituals of Anzac Day is also the work that makes the strongest and most direct challenge to the value of Anzac Day traditions. Mike Parr’s double-sided etching,

Invisible Sun (the other side) (2014), combines a critique of the Anzac liturgy with a blunt personal account of Anzac’s sorry legacy in his own family history. The final line summarises the resolved inheritance; Parr’s father ‘regarded the RSL with contempt and wouldn’t march on Anzac Day’.

Together, the two sides of the work are a dissenting polemic against the veins of resolved triumphalism that run through the orthodox versions of our commemorative rituals. Parr combines a few basic signals (hand-written script, the scratchy patina of archival notepaper, a stray insignia and a marginal doodle) to locate the image in a tradition of battlefront ephemera. The work draws on that tradition in order to claim its aura of unfiltered sincerity. At the same time, if this is battlefront ephemera Parr has just widened the battlefront to take in the ongoing domestic scenarios shaped by the aftershocks of war. Parr places himself in the work because this is his inheritance. But the shadowy, indistinct self portrait, and the interplay it sets up as marginalia to the text, seem to confirm the problematic and irreconcilable nature of this particular family’s Anzac tradition.

All the works in the portfolio could reasonably be placed on a continuum between the direct personal scope of Parr’s work and the epic scale of Fiona Jack’s twenty-page

Survivors’ Roll of Honour (2014). Each is compelling, and together they define the boundaries of the exhibition — in contrast to Parr’s direct, confined and personal work,

Survivors’ Roll of Honour sets in play a vast hinterland of disrupted lives. Working with historian Phil Lascelles, Jack assembled an exhaustive list of every New Zealander who fought in and survived World War I. Every name on Jack’s list (which covers twenty large sheets of paper) carried home the effects of war. The

Survivors’ Roll of Honour shifts the focus of commemoration from what was lost to what was committed. It quantifies a resource provided, a national labour force, and it marks the size of the population that lived afterwards in the ongoing presence of the war. Jack’s dense list of names insists that the record of war cannot be confined by the military categories of battle (casualties, gains, victory, defeat).

The Centenary Portfolio is a curiosity among Anzac’s anniversary excesses. With its serious, reflective temperament, it quietly asserts the value of less orthodox commemorative traditions. While the strength of shared memories can define a community, a shared commitment to remembering is a more resilient bond.

Nick Terrell is a freelance writer who drifted from academia into politics.