I remember walking past the vacant retail space on the corner of Lonsdale and Swanston Streets, quietly charting the course of its transformation. The shop came to be filled, sparingly, with trestle table desks, flat-pack cardboard boxes and rolls of packaging tape. The most salient clue that this store was ready to trade came with the application of the blue and white identity of the light-box sign — Chiang Jiang International Express. Existing somewhere between satellite post office and dingy warehouse backroom, the shopfront had become dedicated to sending domestic packages: bulk bargains, souvenirs and keepsakes overseas.

Stopping at the pedestrian crossing, I looked back to see a couple standing at the window, gawking. They spoke to each other in the language of disapproval; their eyes darted around the store, fingers on the glass, exchanging physical nuances of criticism in an effort to be acknowledged for their disdain. And with all the unfairness for which we judge strangers, I felt certain of their situation — I knew they’d never lived away from their loved ones.

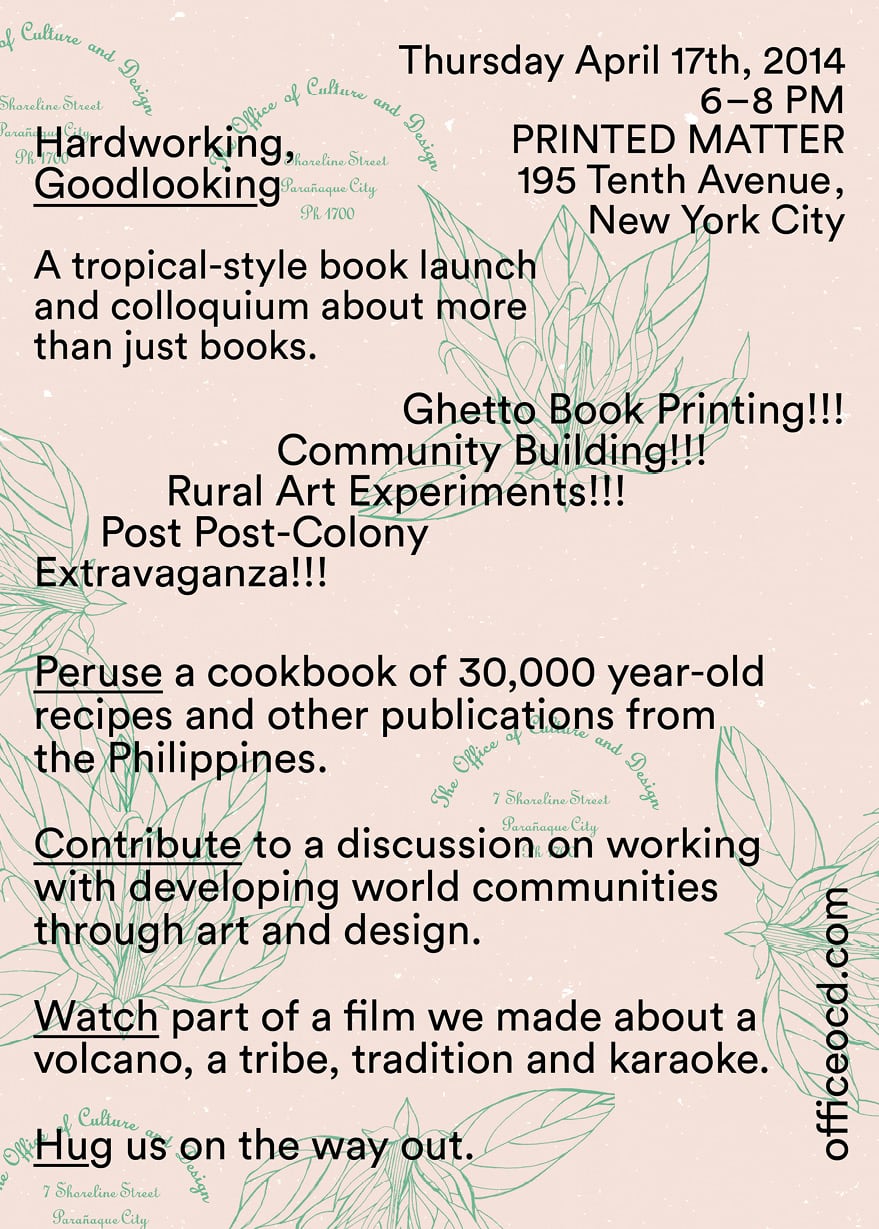

The Office of Culture and Design is a platform for social art practice and cultural research in the Philippines. Clara Lobregat Balaguer is the Director of The OCD; identifying as a writer, artist and self-taught researcher based in Manila. Kristian Henson is a Filipino-American graphic designer based in New York; he is Head of Design at The OCD and co-founder of The OCD’s publishing arm, Hardworking, Goodlooking.

I first discovered The OCD online through documentation of their project, DIY diskarte,1 a series of informal design workshops in collaboration with Ishinomaki Lab and Filipino carpenters. I was drawn in by Clara’s clever, honest and ambitious blogs — she recounted hours spent in unforgiving trapik (traffic), moments lost in translation and most poignantly, an intrinsic sense of worth for the value of a pinoy (Filipino) project, despite the numerous contradictions of facilitating social arts practice. Instantly, I felt close to this project. As a half-Filipina Australian, the role of race, culture and privilege often manifests in both obvious and ambivalent aspects of my arts practice. The sensibility of The OCD brings clarity to some of the clouds that prevent my ability to assimilate into my mum’s culture — our exchange helping to make sense of my role as an artist and strengthen my ties with our shared pinoy culture.

Clara Lobregat Balaguer

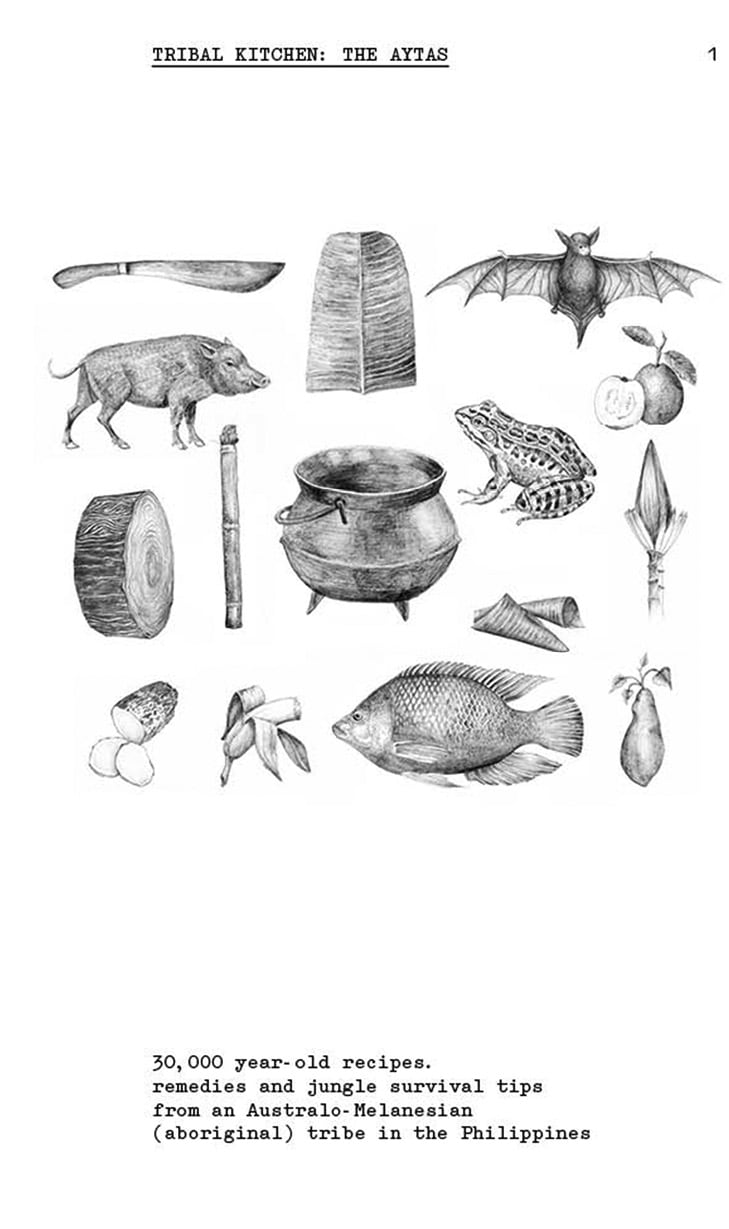

: Since 2010, The OCD has been a platform for social art practice and cultural research, which means we do community-based projects that use art and design as a way to address social issues. As our projects generate experiments that produce content and data, we decided in 2013 to set up a publishing hauz and design studio called Hardworking, Goodlooking (HWGL) to share our findings with others and represent an independent publishing scene in the Philippines. HWGL books also represents a mobile exhibition space for our projects, which are ultimately performative. Unfortunately, our brand of artistic practice and critical exploration of identity does not have a large audience at home. So we must turn to other places for feedback, support and sustenance.

I remember walking past the vacant retail space on the corner of Lonsdale and Swanston Streets, quietly charting the course of its transformation. The shop came to be filled, sparingly, with trestle table desks, flat-pack cardboard boxes and rolls of packaging tape. The most salient clue that this store was ready to trade came with the application of the blue and white identity of the light-box sign — Chiang Jiang International Express. Existing somewhere between satellite post office and dingy warehouse backroom, the shopfront had become dedicated to sending domestic packages: bulk bargains, souvenirs and keepsakes overseas.

Stopping at the pedestrian crossing, I looked back to see a couple standing at the window, gawking. They spoke to each other in the language of disapproval; their eyes darted around the store, fingers on the glass, exchanging physical nuances of criticism in an effort to be acknowledged for their disdain. And with all the unfairness for which we judge strangers, I felt certain of their situation — I knew they’d never lived away from their loved ones.

The Office of Culture and Design is a platform for social art practice and cultural research in the Philippines. Clara Lobregat Balaguer is the Director of The OCD; identifying as a writer, artist and self-taught researcher based in Manila. Kristian Henson is a Filipino-American graphic designer based in New York; he is Head of Design at The OCD and co-founder of The OCD’s publishing arm, Hardworking, Goodlooking.

I first discovered The OCD online through documentation of their project, DIY diskarte,1 a series of informal design workshops in collaboration with Ishinomaki Lab and Filipino carpenters. I was drawn in by Clara’s clever, honest and ambitious blogs — she recounted hours spent in unforgiving trapik (traffic), moments lost in translation and most poignantly, an intrinsic sense of worth for the value of a pinoy (Filipino) project, despite the numerous contradictions of facilitating social arts practice. Instantly, I felt close to this project. As a half-Filipina Australian, the role of race, culture and privilege often manifests in both obvious and ambivalent aspects of my arts practice. The sensibility of The OCD brings clarity to some of the clouds that prevent my ability to assimilate into my mum’s culture — our exchange helping to make sense of my role as an artist and strengthen my ties with our shared pinoy culture.

Clara Lobregat Balaguer

: Since 2010, The OCD has been a platform for social art practice and cultural research, which means we do community-based projects that use art and design as a way to address social issues. As our projects generate experiments that produce content and data, we decided in 2013 to set up a publishing hauz and design studio called Hardworking, Goodlooking (HWGL) to share our findings with others and represent an independent publishing scene in the Philippines. HWGL books also represents a mobile exhibition space for our projects, which are ultimately performative. Unfortunately, our brand of artistic practice and critical exploration of identity does not have a large audience at home. So we must turn to other places for feedback, support and sustenance.

Michelle James

: My memories of Ninoy Aquino International Airport are based on two small certainties — the availability of toilet paper in the CR (‘Comfort Room’ or toilet) and the queue of outbound Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) accompanied by trolleys of plastic-wrapped cardboard boxes with addresses for Dubai, Saudi Arabia, etc.2 With the scale of migration, I would think it unlikely that The OCD are untouched by the phenomenal scale of Filipinos seeking ‘greener pastures’ for lack of opportunity?

CLB

: The exigencies of living in a megacity like Metro Manila makes every single errand an Homeric odyssey. Unbearable traffic, larger and cross-generational family units, mall culture, the incomplete offer (and chaos) of the wet market (fresh meat produce) … all of these challenges compound, making domestic life a team effort. It takes a village to raise a child. This is something internalised in the Filipino family unit, where many of us, women especially, leave home and country to seek better opportunities elsewhere. Once a Spanish friend confided in me that she suspected her Filipino nanny didn’t really love her own children because she had spent so many years away from them. The ignorance of the statement was appalling, but I suppose understandable. It is not the most ideal of situations, as we are plagued with the traumas of a generation raised without parents. But not always is it a trauma. It can be worked to an advantage, as many Filipino families do.

MJ

: Impermanent occupancies and transitory communities become the consequent effects of the OFW, withheld from the rights of citizenship. This status can appear at odds with the balikbayan3 given their acquisition of foreign citizenship, often procuring a more ‘powerful’ passport. Do you have any ideas for ways that art and design can help serve communities affected by long-term absence?

CLB

: Design and art are complicit with the systems that create inequality, making this a difficult question to answer. I am of the mind that trying to work with the system from the inside is a viable answer; using the critical, emotional, even economic power of cultural practice to transform power structures from within. But there is always the doubt about whether the system is too rotten, whether working within set parameters is merely perpetuating what is wrong with neo-liberal Capitalism, shadism,4 strong man-ism … It is a contradiction that each and every project struggles with.

Kristian Henson

: Art and design are tools for communication and agency. In the case of OFWs and the Filipino diaspora at large these tools give our community voice. I feel like Filipinos have been seen for decades as a silent minority. Through art and design we can outwardly project our politics, our anger, our desires, our psychosis and identity. The platform to utter or express such things is not trivial but essential.

Michelle James

: My memories of Ninoy Aquino International Airport are based on two small certainties — the availability of toilet paper in the CR (‘Comfort Room’ or toilet) and the queue of outbound Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) accompanied by trolleys of plastic-wrapped cardboard boxes with addresses for Dubai, Saudi Arabia, etc.2 With the scale of migration, I would think it unlikely that The OCD are untouched by the phenomenal scale of Filipinos seeking ‘greener pastures’ for lack of opportunity?

CLB

: The exigencies of living in a megacity like Metro Manila makes every single errand an Homeric odyssey. Unbearable traffic, larger and cross-generational family units, mall culture, the incomplete offer (and chaos) of the wet market (fresh meat produce) … all of these challenges compound, making domestic life a team effort. It takes a village to raise a child. This is something internalised in the Filipino family unit, where many of us, women especially, leave home and country to seek better opportunities elsewhere. Once a Spanish friend confided in me that she suspected her Filipino nanny didn’t really love her own children because she had spent so many years away from them. The ignorance of the statement was appalling, but I suppose understandable. It is not the most ideal of situations, as we are plagued with the traumas of a generation raised without parents. But not always is it a trauma. It can be worked to an advantage, as many Filipino families do.

MJ

: Impermanent occupancies and transitory communities become the consequent effects of the OFW, withheld from the rights of citizenship. This status can appear at odds with the balikbayan3 given their acquisition of foreign citizenship, often procuring a more ‘powerful’ passport. Do you have any ideas for ways that art and design can help serve communities affected by long-term absence?

CLB

: Design and art are complicit with the systems that create inequality, making this a difficult question to answer. I am of the mind that trying to work with the system from the inside is a viable answer; using the critical, emotional, even economic power of cultural practice to transform power structures from within. But there is always the doubt about whether the system is too rotten, whether working within set parameters is merely perpetuating what is wrong with neo-liberal Capitalism, shadism,4 strong man-ism … It is a contradiction that each and every project struggles with.

Kristian Henson

: Art and design are tools for communication and agency. In the case of OFWs and the Filipino diaspora at large these tools give our community voice. I feel like Filipinos have been seen for decades as a silent minority. Through art and design we can outwardly project our politics, our anger, our desires, our psychosis and identity. The platform to utter or express such things is not trivial but essential.

CLB

: I guess the only thing I could say is that awareness and open negotiation with this innate contradiction is the only way to generate work that could devise a way forward. Another lesson learned is that for social practice to be effective, on a palpable and immediate level, one must involve communities in processes, decision-making and keep long or, at the very least, midterm commitment in mind.

MJ

: Through globalisation, our social progress appears marked by our ability to embody a post-national identity. Is there something to be said about the privilege of those able to live out a ‘transnational identity’ versus the burden of those affiliated with a nation and culture?

CLB

: Transnationality is as much a burden as it is a privilege. The question of identity is not just a nationalistic, racial or cultural concern. I believe it is integral to our experience of being human. Not being able to identify with a place, to call somewhere home, to find a tribe … all of that is profoundly confusing. Especially in this day and age for OFWs and their children moving to places like the US, where the discussion on race and culture has such a strong social prominence.

As a half-Filipina — with racially distinct features, a privileged upbringing away from the poverty line and a hybrid set of cultural influences — it is difficult to explore identity politics because my circumstantial traits set off a bunch of ‘chip-on-the-shoulder’ discourses. Up to a certain point, there is truth in the argument of my not fully belonging to the Filipino cultural value system. The fact that I can observe as an outsider and insider at the same time is advantageous. You are constantly asked to pick a side, manifest either your whiteness or brownness as an absolute. I cannot do that.

KH

: There is fluidity to the Filipino identity, which I think is very powerful. We live at this very specific nexus between so many other countries and cultures. Historically we are traders, sailors, nomadic and multicultural in our economy, which is what one associates with a homogeneous culture. I can only speak as an American citizen. As much as I try to be fully Filipino through all the projects we do in the Philippines, out of respect I have accepted being Filipino-American, an hybrid identity, which I personally feel is neither here nor there.

CLB

: I guess the only thing I could say is that awareness and open negotiation with this innate contradiction is the only way to generate work that could devise a way forward. Another lesson learned is that for social practice to be effective, on a palpable and immediate level, one must involve communities in processes, decision-making and keep long or, at the very least, midterm commitment in mind.

MJ

: Through globalisation, our social progress appears marked by our ability to embody a post-national identity. Is there something to be said about the privilege of those able to live out a ‘transnational identity’ versus the burden of those affiliated with a nation and culture?

CLB

: Transnationality is as much a burden as it is a privilege. The question of identity is not just a nationalistic, racial or cultural concern. I believe it is integral to our experience of being human. Not being able to identify with a place, to call somewhere home, to find a tribe … all of that is profoundly confusing. Especially in this day and age for OFWs and their children moving to places like the US, where the discussion on race and culture has such a strong social prominence.

As a half-Filipina — with racially distinct features, a privileged upbringing away from the poverty line and a hybrid set of cultural influences — it is difficult to explore identity politics because my circumstantial traits set off a bunch of ‘chip-on-the-shoulder’ discourses. Up to a certain point, there is truth in the argument of my not fully belonging to the Filipino cultural value system. The fact that I can observe as an outsider and insider at the same time is advantageous. You are constantly asked to pick a side, manifest either your whiteness or brownness as an absolute. I cannot do that.

KH

: There is fluidity to the Filipino identity, which I think is very powerful. We live at this very specific nexus between so many other countries and cultures. Historically we are traders, sailors, nomadic and multicultural in our economy, which is what one associates with a homogeneous culture. I can only speak as an American citizen. As much as I try to be fully Filipino through all the projects we do in the Philippines, out of respect I have accepted being Filipino-American, an hybrid identity, which I personally feel is neither here nor there.

MJ

: I recently read an article criticising ‘the OFW experience’ as portrayed through a Coca-Cola commercial; three OFWs had the opportunity to fly home to be reunited with their families over Christmas.5 Needless to say, this resonates with the viewer and the ad takes its desired effect. In a nation where drinking Coke is interchangeable with buying bottled water, positioning the Coca-Cola Company as a creative organisation invested in the lives of participants suggests uncomfortable parallels with socially-driven arts practice. Both performing merit-good, opting for creative, even temporary solutions to systemic problems. Can you offer some thoughts on the complexities of navigating the social art and design sphere of a ‘developing nation’?

CLB

: This is a difficult question for anyone practicing in the cultural field, which is dependent on external funding for survival. In the Philippines especially, funding is scarce for cultural projects. This hybrid approach, beyond simply ‘relational’ but actually committed to social justice, is not even considered art by most critical circles here. So you either have to find your own funding, by prostituting yourself as all manner of raket (sideline work) or kind of just take what you can get. This may be an unpopular thought for hard-line activists, but when you’re more along the lines of survivability than sustainability, it’s hard to say no to an extended line of credit. Not that I get those very often…!

Public funds, private funds, market-driven profit, its all subject to the whims and agendas of external agents. Just this year, the Tate Modern had to drop BP as one of its sponsors due to massive protests. The more you pull at the money thread, the more it unravels into controversy. The art world itself is a glaring contradiction of neo-liberality; no matter how radical you may be, the fact that you must engage with the system of institutions, galleries and art media in order for work to be legitimised means you are already complicit. There should be a way to accept this openly, address it, and use the overtly expressed contradiction as a starting point for any artistic endeavour. Transparency, at the end of the day, is the only viable option.

MJ

: Having read your article for Triple Canopy, ‘Tropico Vernacular’, I’ve been thinking about the disconnect between the tourism campaign, ‘It’s More Fun in the Philippines’, and my past visual experiences of Filipino street signage and tarpaulin ads.6 Are Minimalist fonts, a product of European design, used in the campaign to redress the pinoy penchant for excess; to neaten, formalise and make elegant the offerings of jeepney (jeep) rides? Does The OCD propose strategies to decolonise the Filipino self-image? Or is it a necessary part of the mixed Filipino experience?

CLB

: Decolonising local aesthetic, as far as The OCD is concerned, does not mean returning to this idealistic, precolonial, tribal imagery, as if every Filipino had the right to appropriate tribal culture because that’s the only thing they consider ‘pure’ or decolonised. Just because we are brown, doesn’t mean we belong to these tribes. Just because these tribes identify as Filipino, doesn’t mean we have a right to claim their culture as ours and halo-halo (mix-mix) it to our gentrified tastes. That being said — appropriation, when done properly, can be an enriching experience. But only if it reverses the source of power.

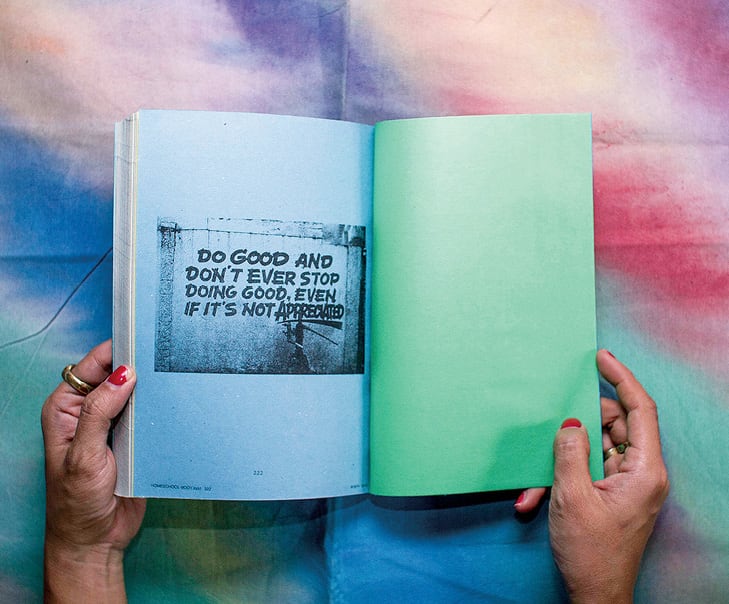

More than departing entirely from any colonial influence, the way we approach decolonising in our books is by encouraging tenderness for the vernacular, everyday aesthetic influences. The stuff you see in lowbrow design at street level. The further away the vernacular designer’s technical knowledge is from Western or Northern processes — hand-made, non-computerised production, for example — the greater the chance of mispronunciation. A step towards decolonisation is not denying that these connections to the occidental aesthetic exist, but rather a shift in the perception of value: what is local, however uncouth, is not of lesser value. It does not merit a whitewashing. It does merit close study and rigorous critical framing. Decolonising local aesthetic is an exploration of what is happening now. It is not a reaching into the past for a pre-colonial root of identity. It is a mining of the present for clues as to who we are — a making visible of our current face without shame for its developing nature.

MJ

: In designing for HWGL, is there a conscious effort to represent a pinoy flavour? Are there any conflicting feelings in regards to being seen as a ‘Filipino representative’ in a broadly Western graphic design world?

KH

: Style in this case is definitely political. I’m a classically trained Modernist photographer for two pretty strong pedigrees: ArtCenter and Yale School of Art. Clara likes to tease me for once drunkenly uttering, ‘Secretly, I’m a Minimalist...’ When I started working with pinoy content and contemporary artworks I imagined the power of strong fundamental Modernist typography and design being transformative within our island setting. It was an international movement so I assumed it was meant to work everywhere. However, when sketching with the actual material I found Modernism regressive and imperialistic. It visually has the same effect of taking artefacts out of context and placing them in a white cube. Beautiful for sure, but what does this mean? It essentialised and fetishised the content. Slowly, I referenced what local Filipino designers would make. Not the classically trained but what was happening on a street level. They work within an economy of means, resourcefulness of technology and freeness of style and influence that is very specific to what a Filipino would create. They became my inspiration, I wanted to design as one of them — making the content more interesting but raising up their craft as well. I feel like local vernacular design goes beyond a style, operating as a legitimate design philosophy. I didn’t set out to make vernacular forms my project but it is just what works best, it excites me, I feel like it’s political and gives The OCD and HWGL its uniqueness in voice.

MJ

: I’d love to talk about the concept of diskarte that The OCD makes reference to in your recent project with Ishinomaki Lab. On my last trip to the Philippines, I was shown an old hand-made yantok (rattan) chair. It had been demoted to the wet kitchen at my grandparent’s house. Which, of course, only meant that we weren’t supposed to sit on it when we visited, though it remained in practical (probably lovable) use by several members of my family. How does The OCD make a point of difference between the Western aesthetic of ‘upcycling’ and Filipino diskarte?

CLB

: I first heard about diskarte, as a design concept, from Pamela Cajilig, who runs a local design thinking collective called Curiosity.ph. She describes it as a strategy taken from the Filipino attitude of making the best of what you have on hand to solve problems efficiently, cheaply, quickly and humorously. DIY is more of a back-to-the-roots movement, a critique of consumerist society wherein self-insufficiency is the norm. Diskarte is a subconscious attitude that stems from the want or lack of resources—from knowing how to solve and accept insurmountable problems in the face of poverty. We tend to see diskarte attitude as something to be both proud and ashamed of, as these patchwork solutions arise when money (or another other desirable asset) is missing.

Even though in the US there is a strong consciousness for recycling, it exists alongside this cavalier faith in the renewability, the false abundance of all resources. This is the contradiction of the most pedestrian form of Western eco-sensibility. In the Philippines, on the other hand, it starts at home with people saving and using all sorts of scraps and fragments to make diskarte. Then the local garbage men collect waste in wooden carts and sacks, roving the neighbourhood like the tool sharpener guys, the sellers of balut (incubated duck fetus-eggs) and taho (soybean curd with tapioca and syrup) and other mobile cottage industry microbusinesses. They buy or simply collect recyclable paper, bottles and plastic to resell to junk dealers, maybe even back to Coca-Cola factories. Larger scale garbage collectors, with proper trucks and stuff, outsource the service to junk shops or simply bring unsegregated trash to landfills, where hundreds of informal dwellers pick through the waste for monetary objects. Chamba, which is something like luck, also affects diskarte. Your efforts to make diskarte always require some element of luck, fatalistic and somewhat effortless auspiciousness. When you live so close to want and have so much faith in the supernatural, the idea of life becomes a set of bets you may win or lose—so you roll the dice and pray for favour as a natural component of action.

The last particularity of diskarte involves the concept of resilient humour. A not-so-pretty guy can get a hot girl with the power of his diskarte—his humorous and engaging conversation. Same goes for site-specific design solutions. My recent favourite diskarte find is a bench made for a patch of sidewalk that had both an elevated and depressed area. So they built a bench with one set of legs shorter than the other so it could be positioned, presumably, to maximise the hours of shade and not be in the way of passers-by. Though, maybe they just liked the view better sitting in that direction. It’s a funny looking thing and you can’t help but crack a grin when you see it. If you see it, that is. Often, we take for granted these tiny moments of wry Filipino ingenuity.

MJ

: Given your significant geographical distance from one another—New York to Manila— I wonder what each of you would choose to send the other in a classic cardboard balikbayan box, given you could afford the patience of waiting for the shipping containers to arrive in six months or so...

KH

: Clara wants books that I know, for a fact, she would be offended if that wasn’t in the box. I would probably send her 99% books, mostly reference books for her papers and maybe a couple of flea market and side walk gems. Shipping costs would be murder but anything for my ate (big sister). The 1% would be just enough room for a mismatched teacup and saucer for her collection.

CLB

: I’d send Kristian random printed matter, all sorts of cottage industry crafts, a few custom embroidered patches, a fishing net bag, and some spiritual voodoo knick-knacks from Quiapo Market. I’d only want books—loads of them. Maybe some Fruit Roll Ups, but I really can’t have any sugar, so he shouldn’t send them to me, even hypothetically.

MJ

: I recently read an article criticising ‘the OFW experience’ as portrayed through a Coca-Cola commercial; three OFWs had the opportunity to fly home to be reunited with their families over Christmas.5 Needless to say, this resonates with the viewer and the ad takes its desired effect. In a nation where drinking Coke is interchangeable with buying bottled water, positioning the Coca-Cola Company as a creative organisation invested in the lives of participants suggests uncomfortable parallels with socially-driven arts practice. Both performing merit-good, opting for creative, even temporary solutions to systemic problems. Can you offer some thoughts on the complexities of navigating the social art and design sphere of a ‘developing nation’?

CLB

: This is a difficult question for anyone practicing in the cultural field, which is dependent on external funding for survival. In the Philippines especially, funding is scarce for cultural projects. This hybrid approach, beyond simply ‘relational’ but actually committed to social justice, is not even considered art by most critical circles here. So you either have to find your own funding, by prostituting yourself as all manner of raket (sideline work) or kind of just take what you can get. This may be an unpopular thought for hard-line activists, but when you’re more along the lines of survivability than sustainability, it’s hard to say no to an extended line of credit. Not that I get those very often…!

Public funds, private funds, market-driven profit, its all subject to the whims and agendas of external agents. Just this year, the Tate Modern had to drop BP as one of its sponsors due to massive protests. The more you pull at the money thread, the more it unravels into controversy. The art world itself is a glaring contradiction of neo-liberality; no matter how radical you may be, the fact that you must engage with the system of institutions, galleries and art media in order for work to be legitimised means you are already complicit. There should be a way to accept this openly, address it, and use the overtly expressed contradiction as a starting point for any artistic endeavour. Transparency, at the end of the day, is the only viable option.

MJ

: Having read your article for Triple Canopy, ‘Tropico Vernacular’, I’ve been thinking about the disconnect between the tourism campaign, ‘It’s More Fun in the Philippines’, and my past visual experiences of Filipino street signage and tarpaulin ads.6 Are Minimalist fonts, a product of European design, used in the campaign to redress the pinoy penchant for excess; to neaten, formalise and make elegant the offerings of jeepney (jeep) rides? Does The OCD propose strategies to decolonise the Filipino self-image? Or is it a necessary part of the mixed Filipino experience?

CLB

: Decolonising local aesthetic, as far as The OCD is concerned, does not mean returning to this idealistic, precolonial, tribal imagery, as if every Filipino had the right to appropriate tribal culture because that’s the only thing they consider ‘pure’ or decolonised. Just because we are brown, doesn’t mean we belong to these tribes. Just because these tribes identify as Filipino, doesn’t mean we have a right to claim their culture as ours and halo-halo (mix-mix) it to our gentrified tastes. That being said — appropriation, when done properly, can be an enriching experience. But only if it reverses the source of power.

More than departing entirely from any colonial influence, the way we approach decolonising in our books is by encouraging tenderness for the vernacular, everyday aesthetic influences. The stuff you see in lowbrow design at street level. The further away the vernacular designer’s technical knowledge is from Western or Northern processes — hand-made, non-computerised production, for example — the greater the chance of mispronunciation. A step towards decolonisation is not denying that these connections to the occidental aesthetic exist, but rather a shift in the perception of value: what is local, however uncouth, is not of lesser value. It does not merit a whitewashing. It does merit close study and rigorous critical framing. Decolonising local aesthetic is an exploration of what is happening now. It is not a reaching into the past for a pre-colonial root of identity. It is a mining of the present for clues as to who we are — a making visible of our current face without shame for its developing nature.

MJ

: In designing for HWGL, is there a conscious effort to represent a pinoy flavour? Are there any conflicting feelings in regards to being seen as a ‘Filipino representative’ in a broadly Western graphic design world?

KH

: Style in this case is definitely political. I’m a classically trained Modernist photographer for two pretty strong pedigrees: ArtCenter and Yale School of Art. Clara likes to tease me for once drunkenly uttering, ‘Secretly, I’m a Minimalist...’ When I started working with pinoy content and contemporary artworks I imagined the power of strong fundamental Modernist typography and design being transformative within our island setting. It was an international movement so I assumed it was meant to work everywhere. However, when sketching with the actual material I found Modernism regressive and imperialistic. It visually has the same effect of taking artefacts out of context and placing them in a white cube. Beautiful for sure, but what does this mean? It essentialised and fetishised the content. Slowly, I referenced what local Filipino designers would make. Not the classically trained but what was happening on a street level. They work within an economy of means, resourcefulness of technology and freeness of style and influence that is very specific to what a Filipino would create. They became my inspiration, I wanted to design as one of them — making the content more interesting but raising up their craft as well. I feel like local vernacular design goes beyond a style, operating as a legitimate design philosophy. I didn’t set out to make vernacular forms my project but it is just what works best, it excites me, I feel like it’s political and gives The OCD and HWGL its uniqueness in voice.

MJ

: I’d love to talk about the concept of diskarte that The OCD makes reference to in your recent project with Ishinomaki Lab. On my last trip to the Philippines, I was shown an old hand-made yantok (rattan) chair. It had been demoted to the wet kitchen at my grandparent’s house. Which, of course, only meant that we weren’t supposed to sit on it when we visited, though it remained in practical (probably lovable) use by several members of my family. How does The OCD make a point of difference between the Western aesthetic of ‘upcycling’ and Filipino diskarte?

CLB

: I first heard about diskarte, as a design concept, from Pamela Cajilig, who runs a local design thinking collective called Curiosity.ph. She describes it as a strategy taken from the Filipino attitude of making the best of what you have on hand to solve problems efficiently, cheaply, quickly and humorously. DIY is more of a back-to-the-roots movement, a critique of consumerist society wherein self-insufficiency is the norm. Diskarte is a subconscious attitude that stems from the want or lack of resources—from knowing how to solve and accept insurmountable problems in the face of poverty. We tend to see diskarte attitude as something to be both proud and ashamed of, as these patchwork solutions arise when money (or another other desirable asset) is missing.

Even though in the US there is a strong consciousness for recycling, it exists alongside this cavalier faith in the renewability, the false abundance of all resources. This is the contradiction of the most pedestrian form of Western eco-sensibility. In the Philippines, on the other hand, it starts at home with people saving and using all sorts of scraps and fragments to make diskarte. Then the local garbage men collect waste in wooden carts and sacks, roving the neighbourhood like the tool sharpener guys, the sellers of balut (incubated duck fetus-eggs) and taho (soybean curd with tapioca and syrup) and other mobile cottage industry microbusinesses. They buy or simply collect recyclable paper, bottles and plastic to resell to junk dealers, maybe even back to Coca-Cola factories. Larger scale garbage collectors, with proper trucks and stuff, outsource the service to junk shops or simply bring unsegregated trash to landfills, where hundreds of informal dwellers pick through the waste for monetary objects. Chamba, which is something like luck, also affects diskarte. Your efforts to make diskarte always require some element of luck, fatalistic and somewhat effortless auspiciousness. When you live so close to want and have so much faith in the supernatural, the idea of life becomes a set of bets you may win or lose—so you roll the dice and pray for favour as a natural component of action.

The last particularity of diskarte involves the concept of resilient humour. A not-so-pretty guy can get a hot girl with the power of his diskarte—his humorous and engaging conversation. Same goes for site-specific design solutions. My recent favourite diskarte find is a bench made for a patch of sidewalk that had both an elevated and depressed area. So they built a bench with one set of legs shorter than the other so it could be positioned, presumably, to maximise the hours of shade and not be in the way of passers-by. Though, maybe they just liked the view better sitting in that direction. It’s a funny looking thing and you can’t help but crack a grin when you see it. If you see it, that is. Often, we take for granted these tiny moments of wry Filipino ingenuity.

MJ

: Given your significant geographical distance from one another—New York to Manila— I wonder what each of you would choose to send the other in a classic cardboard balikbayan box, given you could afford the patience of waiting for the shipping containers to arrive in six months or so...

KH

: Clara wants books that I know, for a fact, she would be offended if that wasn’t in the box. I would probably send her 99% books, mostly reference books for her papers and maybe a couple of flea market and side walk gems. Shipping costs would be murder but anything for my ate (big sister). The 1% would be just enough room for a mismatched teacup and saucer for her collection.

CLB

: I’d send Kristian random printed matter, all sorts of cottage industry crafts, a few custom embroidered patches, a fishing net bag, and some spiritual voodoo knick-knacks from Quiapo Market. I’d only want books—loads of them. Maybe some Fruit Roll Ups, but I really can’t have any sugar, so he shouldn’t send them to me, even hypothetically.

Michelle James is an artist and writer based in Melbourne. Presented here is her full interview with Clara Lobregat Balaguer and Kristian Henson from The Office for Culture and Design, a platform for social art practice and cultural research in the Philippines. An excerpt of this interview appears in the print edition of un Magazine 10.2.

1. diskarte is a strategy taken from the Filipino attitude of making the best of what you have on hand to solve problems efficiently, cheaply, quickly and humorously.

2. Overseas Filipino Workers — also known as OFWs are Filipino citizens working abroad, often on a long-term contract basis.

3. A balikbayan is considered to be a Filipino who has renounced native citizenship to be naturalised into a foreign country.

4. shadism, in a Filipino context, is racial prejudice based on the social stigma of being a darker shade of skin.

5. Fritz Luther C. Pino, ‘Neoliberal happiness: overseas Filipino works and Coca-Cola’s Christmas commercial’, Transnational Social Review 4:2–3, 2014, pp. 299–302.

[^6]: Clara Lobregat Balaguer, ‘Tropico Vernacular: The New Society Tagalog in Helvetica, and one-stop sari sari stores. A recent history of graphic design and nationalism in the Philippines’, Triple Canopy, 2016, pp. 1–30.