Amy Spiers and Catherine Ryan’s performance, The Least of the Doorkeepers (It is Possible but Not at the Moment) (2016), involved a pair of uniformed men moving two razor wire fences on wheeled bases around Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) on the opening night of the survey exhibition Borders, Barriers, Walls. The walls were moved in choreographed patterns, which interrupted, rerouted and blocked the movement of gallery attendees at the opening. The structures used in the performance — two mobile razor wire fences — will remain in the space over the course of the exhibition. Anusha Kenny spoke with Amy Spiers and Catherine Ryan a week after the opening of the exhibition.

If we can begin with discussion of Borders, Barriers, Walls, it is interesting to consider the show against the background of the 19th Biennale of Sydney and that moment of institutional critique, where the criticality played out in the conversations between the artists and the board (and the decision to explicitly not participate in that exhibition). In contrast, the MUMA show involves artists who are presenting critical work about a topic — borders, and their enforcement — within an institutional framework. Do you have any comment on how these approaches to criticality and these exhibitions relate?

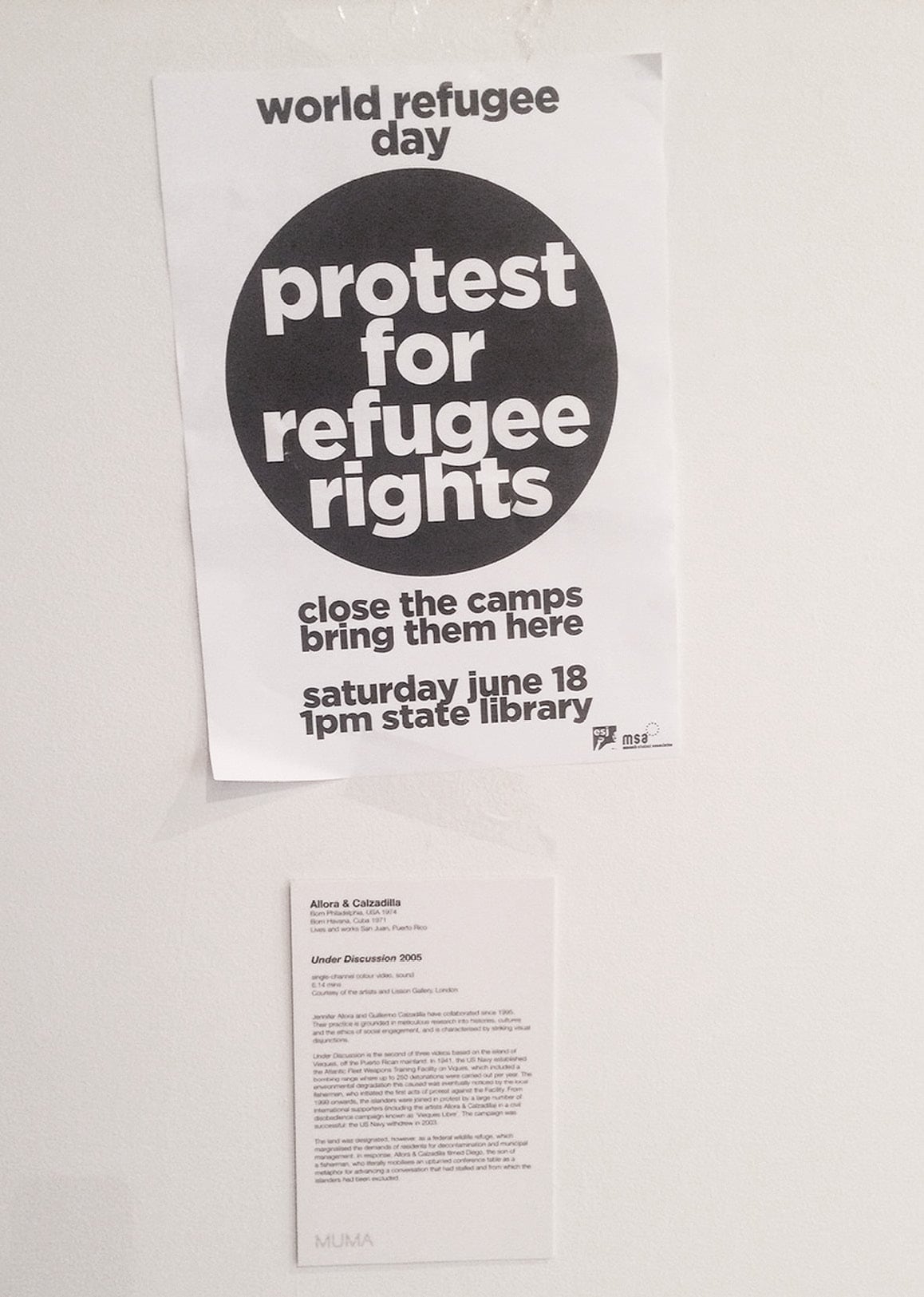

I think it’s really interesting, the kind of anxieties that people have about what artists should be doing in relation to politics. Even at the discussion panel we were at [at MUMA on 18 May 2016], an artist got up and asked a question about the Sydney Biennale boycott and how artists should respond to politics. I want to show you this picture I’ve got on my phone [shows photo of a flyer for a protest for refugee rights taped above Amy and Catherine’s work details on the wall of the MUMA gallery] as it gives a sense of the anxiety around the show. Someone has put these posters on the wall of the gallery.

Do you think that that poster was put up ‘with’ your art work, or is the intention to say, ‘f––k you, we’re doing something real’?

AS: I think there is a genuine anxiety that we should be doing more, and people don’t feel that the art in the show is doing enough, and I think that’s something really interesting. We’re in this terrible impasse in politics, and people find it unsatisfactory to look at artists who are ‘just’ reflecting on borders. They want action. But I believe that artists looking at borders and thinking about borders is part of this ‘doing something’.

I would agree. I think it’s good that the Biennale of Sydney boycott is continuing to be discussed within Borders, Barriers, Walls, because in many ways it’s a success story, but one that’s still being written. From my perspective, a big leap forward was made there in regards to how much knowledge there is about divestment as a strategy, which is still having political effects now. Transfield, which is now known as Broadspectrum, is being bought by a Spanish company called Ferrovial, and they are thinking that mandatory detention is not a good business to get into, essentially. There’s also been the development of the ‘No Business In Abuse’ campaign. The boycott conversation is part of this narrative.

The fact is that MUMA exists as an institution, and they do put on shows. So the question is, what should be in the shows that they put on? I don’t think everyone should just stop making art and get into activism. But by the same token, no one should feel that enough has been done because someone has made a work about borders.

In terms of audience, who was The Least of the Doorkeepers (It is Possible but Not at the Moment) for?

I think it was for the people in the gallery. When we were thinking about a work that moved people through the space, we definitely didn’t want it to feel like ‘Refugee: The Gallery Experience’. We wanted it to be a mediation on the technology of the border, and the theatre of power. We called it The Least of the Doorkeepers because we wanted to thematise the fact that this is a performance, this is not the real thing. If you get briefly trapped in a gallery by our razor wire, this will be the least of the borders that you will encounter. The reference is to Kafka’s ‘Before the Law’, where the man from the country wants to get into the law, and the doorkeeper says, ‘well you can, but not at the moment, and there’s a second and third doorkeeper after me, and they just get worse and worse as you go in’. Our work refers to itself in a way, in saying that ‘this is the least of the things that are wrong in the world’.

It occurred to me that there are resonances between some of your works and Jane Elliott’s Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes exercises, which involve taking a group of people and treating the brown-eyed people as superior to the blue-eyed people, giving the (usually white) blue-eyed people an experience of what discrimination feels like. Your work explores arbitrary exercises of power — like Ordering the Public, which involved innocuous actions being made ‘illegal’ for a period of time. What is the experience of your work for people who have experienced the exercise of power in a negative way? Are you just speaking to people who have not experienced the arbitrariness of the law?

Certain similarities between our work and Jane Elliot’s work have occurred to us. I can see why you draw the comparison. I don’t think our work is just for people who have ‘had a nice ride’ in life. I think it’s about getting people to notice technologies of control or authority that they might encounter all the time but that they don’t think about. Just because you’re experiencing something controlling or oppressive doesn’t mean that you’ll even notice it necessarily. It took me years of being treated differently as a woman before I really noticed it. It’s not about getting people to change roles like Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes does, but it’s perhaps about getting people to notice details about how these discriminatory technologies work and, hopefully in doing that, they might change their habits of perception. I think what you notice is very much a matter of habit.

Is the ‘technology’ of The Least of the Doorkeepers the barbed wire fence?

Yes, and the wheels. The idea that ‘this is here now, but it could go elsewhere’. Rules can be rearranged and it won’t be for your benefit. Centrelink will change your reporting requirements and you’ll be on the receiving end of it, but no one will have consulted you. The objects in the MUMA show — they are the concretisation of this in a way.

We were thinking about the ways in which we might encounter the apparatus of a border. One example we looked to for inspiration was when the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) had a security scare last year and erected a huge fence that was used to process people. It just meant that it took longer for people to get into the MCG. So often our experiences of security and fences are things that frustrate our easy path into a place. Once they determine if you’re the ‘right’ sort of person, you pass through them, as in airports. When we think about our choreography and the way we move obstructive objects through space, you encounter them, and you may have to reroute, but you are still let through. We started to see borders as a technology that sieves us in and out but stops others.

Amy, I want to ask you about how your work with Catherine relates to your previous practice. One of the first projects of yours I saw was Lonely Hearts at Platform in 2012, with Lara Thoms, which aimed to bring dating profiles into the gallery. I also remember Agents of Proximity, the Brunswick travel service. It seemed that your aim was to have the audience make themselves vulnerable through participation in the work, or otherwise to create a sense of interconnectedness. It could be said, using criminological language, that your previous works were ‘pro-social’ and about creating human connection, but it seems now that you have taken a more punitive turn in your engagement with your audience. I am wondering whether you considered that the first approach to the audience to have failed you in some way? What accounts for the shift?

Yes. I started having misgivings about the live art, relational works I was seeing around me, which I was contributing to. There was a phase when I was uncertain about these works that were trying to bring people together. I then encountered Claire Bishop’s critique of relational art, which echoed my own misgivings about the fact that the people who attended these works and were being ‘brought together’ tended to be likeminded people in any case. I started engaging in the critiques about who is not participating in these sorts of works, and asking why is it so hard for Agents of Proximity to get anyone to participate in the work who isn’t a twenty-something artist? I started my Masters trying to deal with this question. I started thinking about the limits of sociability and what that can actually achieve politically. I started thinking about the more intractable situations that won’t be fixed by just getting people together and feeling more comfortable.

My Masters looked at the politics of antagonism, and the idea that conflict is a necessary aspect of politics, and then I was trying to think about how art can reflect these realities, rather than pretending that we can become one big, happy, harmonious community if we spend more time with one another. That is problematic.

Anusha Kenny is a writer and lawyer from Melbourne. She would like to thank Liang Luscome, Charlie Sofo and Isadora Vaughan for their insights on the exhibition, which contributed to the questions asked in this interview.