THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED

1–29 May 2016

SUCCESS

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Michael Candy,

Antoinette J Citizen, JD Reforma, Andrew Varano,

Tim Woodward, Greatest Hits (Gavin Bell, Jarrah

de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn)

Curated by Sarah Werkmeister & Tim Woodward

To start with, I get the opening hours wrong, and make the half-hour train trip from Perth to Fremantle when the gallery is shut. Dale, one of the directors of SUCCESS, comes up from the basement to meet me on the shop floor of the former Myer building. He leads me behind the heavy red velvet curtain that encircles the central escalators. They’re stationary now, and we descend, the tread slightly too steep for comfort.

Downstairs, below the surface, it’s pitch black; they’ve taken out most of the overhead lights. Spot-lit islands glimmer off the pillars that stretch into the distance. Once this floor was the Menswear Department but for the past ten years it’s been closed to the public. Dale picks up a scooter and skims away over the concrete floor to show me an artwork in the former change room. It’s fifty metres of darkness in every direction. SUCCESS is not like any other place I’ve seen.

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED, the show I’m here to review, is in a side-space that’s well-lit and somewhat more attuned to human scale. Curated by Sarah Werkmeister and Tim Woodward, the exhibition explores surveillance; it feels appropriate that it’s located in a kind of below-ground bunker. The seven works examine surveillance from a variety of angles, touching on phone-tapping, censorship, geo-blocking, reality television, newspapers and social media.

In

Looking at you (2005–14), JD Reforma probes everyday personal surveillance and the ‘othering’ of the surveilling gaze. Texts have been pulled from the ‘Here’s Looking at you’ section of

mX (a commuter newspaper circulated in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane between 2001–15). A kind of Missed Connections for those observing others on the train, these letters attempt to reach through the fourth wall that commuters put up around themselves. Appearing on a screen one after the other, it becomes clear that those being ‘looked at’ in these selected texts are all profiled as ‘Asian’, a perceived identity with no acknowledgement of cultural distinctions or lived experience. Simply and pointedly, this piece brings to attention the overt and subtle power dynamics of race.

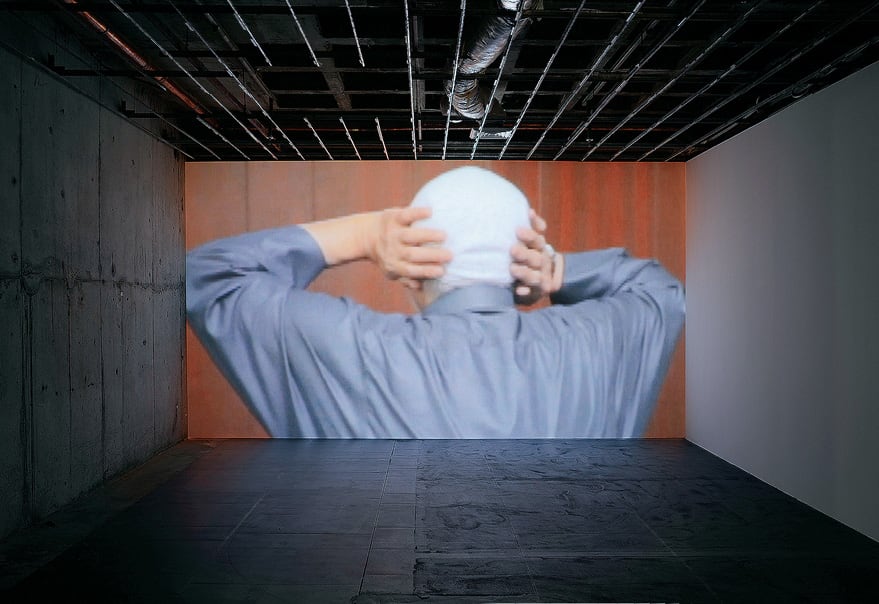

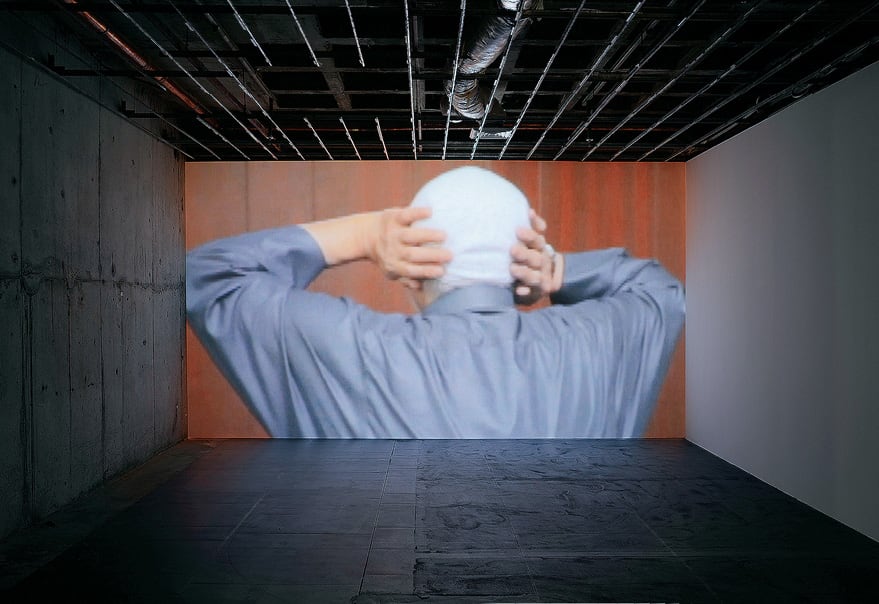

In a show about surveillance in the current environment of anti-Islamic paranoia, I’m glad to see a work that engages directly with Islam. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s

The All-Hearing (2014), focuses on aural surveillance. The film documents two sheikhs in Cairo delivering sermons about noise-pollution, the sermons ironically spilling out into the streets through the mosques’ speaker systems. This action deliberately violated a recent law decreeing that such talks would be only about government-sanctioned topics. Taking on issues of control and censorship, as well as religion,

The All-Hearing positions the sheikh as a voice of authority echoing into the streets, but above this is the ominous, unseen, all-hearing ear of the government.

Several of the works in the exhibition rest on intricate catalogues of obscure (to me) knowledge, which can make them difficult to engage with. A large photograph of a hand,

Untitled (Nasubi) (2016), by Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits) has been imprinted on cotton using UV degradation methods, the image softly blue. This turns out to reference a Japanese game show in which a comedian, Nasubi, lived in an apartment for two years, naked, subsisting on winnings from online sweepstakes. He knew he was being filmed but not the extent. The image is from the final episode, the moment of the big reveal: he is shown that the apartment was in fact a television studio and raises his hand in shock. The context is the most interesting thing about this work and it’s unfortunate that there’s no way into it without reading the catalogue text.

Two artists, Antoinette J Citizen and Michael Candy, make use of live-feed surveillance technologies. Citizen’s work,

Method for Mapping (2016), is an inkjet printer that produces a tiny line of colour every minute in a continuous, brightly-striped printout. Ostensibly the colour relates to the artist’s mood or environment at the time, but this ambiguous data is impossible to interpret. The piece points to social media sites that attempt to track and market our moods and emotions based on the words, clicks and emoji we feed into them. However, this work suffers from its proximity to Michael Candy’s

Digital Empathy Device (2016). Beside a piece about large-scale tragedy, Citizen’s work — though technically complex — can come across as mere naval-gazing.

Digital Empathy Device is a highly resolved work, the strongest in the exhibition. Its physical form is a chrome head, crowned with wires, two syringes of tears and a tiny motor. A minuscule tube travels from each syringe, ending at the corner of each eye. On the next plinth is a cobbled-together device of wires and batteries, that looks suspicious but is apparently a mobile phone receptor. This is linked to an online, citizen-run service called LiveMap, which collates and disseminates live information about bombings and attacks in war zones around the world — in this case, Syria. When an attack is reported in the region, a phone-triggered signal causes the head to cry a single tear. An accompanying video shows the device being made in a hotel room and then attached to a Parisian statue which symbolises the French republic and égalité.

Because I’m there outside of opening hours, Dale is doing maintenance on

Digital Empathy Device. ‘It’s not broken’, he explains, ‘it’s just been a busy month. It’s run out of tears.’

This takes a moment to sink in. The human brain is not capable of infinite empathy. After a certain point it shuts down. It has to. We may be postmodern but our brains are Stone Age, still only wired to interact closely with a small group of people. Eloquently, devastatingly,

Digital Empathy Device speaks to this gap between reality and emotional response.

When the tears have been topped up, Liz, another director, offers to make it cry so I can see it in action. She takes out her phone and calls a number. The crown buzzes abruptly and a tear slithers down the polished face. Moments later, it buzzes again and a second tear rolls from the other eye.

I thank Liz. ‘Oh’, she says, ‘the second one wasn’t from me calling it. That one was real.’

I am standing in a lit-up room at the edge of a dark expanse under the ground, and somewhere in the world a bomb just exploded. The face of the statue is eyeless and cold. This one is real.

Anna Dunnill is an artist and writer from Perth.

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED

1–29 May 2016

SUCCESS

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Michael Candy,

Antoinette J Citizen, JD Reforma, Andrew Varano,

Tim Woodward, Greatest Hits (Gavin Bell, Jarrah

de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn)

Curated by Sarah Werkmeister & Tim Woodward

To start with, I get the opening hours wrong, and make the half-hour train trip from Perth to Fremantle when the gallery is shut. Dale, one of the directors of SUCCESS, comes up from the basement to meet me on the shop floor of the former Myer building. He leads me behind the heavy red velvet curtain that encircles the central escalators. They’re stationary now, and we descend, the tread slightly too steep for comfort.

Downstairs, below the surface, it’s pitch black; they’ve taken out most of the overhead lights. Spot-lit islands glimmer off the pillars that stretch into the distance. Once this floor was the Menswear Department but for the past ten years it’s been closed to the public. Dale picks up a scooter and skims away over the concrete floor to show me an artwork in the former change room. It’s fifty metres of darkness in every direction. SUCCESS is not like any other place I’ve seen.

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED, the show I’m here to review, is in a side-space that’s well-lit and somewhat more attuned to human scale. Curated by Sarah Werkmeister and Tim Woodward, the exhibition explores surveillance; it feels appropriate that it’s located in a kind of below-ground bunker. The seven works examine surveillance from a variety of angles, touching on phone-tapping, censorship, geo-blocking, reality television, newspapers and social media.

In Looking at you (2005–14), JD Reforma probes everyday personal surveillance and the ‘othering’ of the surveilling gaze. Texts have been pulled from the ‘Here’s Looking at you’ section of mX (a commuter newspaper circulated in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane between 2001–15). A kind of Missed Connections for those observing others on the train, these letters attempt to reach through the fourth wall that commuters put up around themselves. Appearing on a screen one after the other, it becomes clear that those being ‘looked at’ in these selected texts are all profiled as ‘Asian’, a perceived identity with no acknowledgement of cultural distinctions or lived experience. Simply and pointedly, this piece brings to attention the overt and subtle power dynamics of race.

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED

1–29 May 2016

SUCCESS

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Michael Candy,

Antoinette J Citizen, JD Reforma, Andrew Varano,

Tim Woodward, Greatest Hits (Gavin Bell, Jarrah

de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn)

Curated by Sarah Werkmeister & Tim Woodward

To start with, I get the opening hours wrong, and make the half-hour train trip from Perth to Fremantle when the gallery is shut. Dale, one of the directors of SUCCESS, comes up from the basement to meet me on the shop floor of the former Myer building. He leads me behind the heavy red velvet curtain that encircles the central escalators. They’re stationary now, and we descend, the tread slightly too steep for comfort.

Downstairs, below the surface, it’s pitch black; they’ve taken out most of the overhead lights. Spot-lit islands glimmer off the pillars that stretch into the distance. Once this floor was the Menswear Department but for the past ten years it’s been closed to the public. Dale picks up a scooter and skims away over the concrete floor to show me an artwork in the former change room. It’s fifty metres of darkness in every direction. SUCCESS is not like any other place I’ve seen.

THE NUMBER YOU HAVE REACHED, the show I’m here to review, is in a side-space that’s well-lit and somewhat more attuned to human scale. Curated by Sarah Werkmeister and Tim Woodward, the exhibition explores surveillance; it feels appropriate that it’s located in a kind of below-ground bunker. The seven works examine surveillance from a variety of angles, touching on phone-tapping, censorship, geo-blocking, reality television, newspapers and social media.

In Looking at you (2005–14), JD Reforma probes everyday personal surveillance and the ‘othering’ of the surveilling gaze. Texts have been pulled from the ‘Here’s Looking at you’ section of mX (a commuter newspaper circulated in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane between 2001–15). A kind of Missed Connections for those observing others on the train, these letters attempt to reach through the fourth wall that commuters put up around themselves. Appearing on a screen one after the other, it becomes clear that those being ‘looked at’ in these selected texts are all profiled as ‘Asian’, a perceived identity with no acknowledgement of cultural distinctions or lived experience. Simply and pointedly, this piece brings to attention the overt and subtle power dynamics of race.

In a show about surveillance in the current environment of anti-Islamic paranoia, I’m glad to see a work that engages directly with Islam. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The All-Hearing (2014), focuses on aural surveillance. The film documents two sheikhs in Cairo delivering sermons about noise-pollution, the sermons ironically spilling out into the streets through the mosques’ speaker systems. This action deliberately violated a recent law decreeing that such talks would be only about government-sanctioned topics. Taking on issues of control and censorship, as well as religion, The All-Hearing positions the sheikh as a voice of authority echoing into the streets, but above this is the ominous, unseen, all-hearing ear of the government.

Several of the works in the exhibition rest on intricate catalogues of obscure (to me) knowledge, which can make them difficult to engage with. A large photograph of a hand, Untitled (Nasubi) (2016), by Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits) has been imprinted on cotton using UV degradation methods, the image softly blue. This turns out to reference a Japanese game show in which a comedian, Nasubi, lived in an apartment for two years, naked, subsisting on winnings from online sweepstakes. He knew he was being filmed but not the extent. The image is from the final episode, the moment of the big reveal: he is shown that the apartment was in fact a television studio and raises his hand in shock. The context is the most interesting thing about this work and it’s unfortunate that there’s no way into it without reading the catalogue text.

Two artists, Antoinette J Citizen and Michael Candy, make use of live-feed surveillance technologies. Citizen’s work, Method for Mapping (2016), is an inkjet printer that produces a tiny line of colour every minute in a continuous, brightly-striped printout. Ostensibly the colour relates to the artist’s mood or environment at the time, but this ambiguous data is impossible to interpret. The piece points to social media sites that attempt to track and market our moods and emotions based on the words, clicks and emoji we feed into them. However, this work suffers from its proximity to Michael Candy’s Digital Empathy Device (2016). Beside a piece about large-scale tragedy, Citizen’s work — though technically complex — can come across as mere naval-gazing.

Digital Empathy Device is a highly resolved work, the strongest in the exhibition. Its physical form is a chrome head, crowned with wires, two syringes of tears and a tiny motor. A minuscule tube travels from each syringe, ending at the corner of each eye. On the next plinth is a cobbled-together device of wires and batteries, that looks suspicious but is apparently a mobile phone receptor. This is linked to an online, citizen-run service called LiveMap, which collates and disseminates live information about bombings and attacks in war zones around the world — in this case, Syria. When an attack is reported in the region, a phone-triggered signal causes the head to cry a single tear. An accompanying video shows the device being made in a hotel room and then attached to a Parisian statue which symbolises the French republic and égalité.

Because I’m there outside of opening hours, Dale is doing maintenance on Digital Empathy Device. ‘It’s not broken’, he explains, ‘it’s just been a busy month. It’s run out of tears.’

This takes a moment to sink in. The human brain is not capable of infinite empathy. After a certain point it shuts down. It has to. We may be postmodern but our brains are Stone Age, still only wired to interact closely with a small group of people. Eloquently, devastatingly, Digital Empathy Device speaks to this gap between reality and emotional response.

When the tears have been topped up, Liz, another director, offers to make it cry so I can see it in action. She takes out her phone and calls a number. The crown buzzes abruptly and a tear slithers down the polished face. Moments later, it buzzes again and a second tear rolls from the other eye.

I thank Liz. ‘Oh’, she says, ‘the second one wasn’t from me calling it. That one was real.’

I am standing in a lit-up room at the edge of a dark expanse under the ground, and somewhere in the world a bomb just exploded. The face of the statue is eyeless and cold. This one is real.

In a show about surveillance in the current environment of anti-Islamic paranoia, I’m glad to see a work that engages directly with Islam. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The All-Hearing (2014), focuses on aural surveillance. The film documents two sheikhs in Cairo delivering sermons about noise-pollution, the sermons ironically spilling out into the streets through the mosques’ speaker systems. This action deliberately violated a recent law decreeing that such talks would be only about government-sanctioned topics. Taking on issues of control and censorship, as well as religion, The All-Hearing positions the sheikh as a voice of authority echoing into the streets, but above this is the ominous, unseen, all-hearing ear of the government.

Several of the works in the exhibition rest on intricate catalogues of obscure (to me) knowledge, which can make them difficult to engage with. A large photograph of a hand, Untitled (Nasubi) (2016), by Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer and Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits) has been imprinted on cotton using UV degradation methods, the image softly blue. This turns out to reference a Japanese game show in which a comedian, Nasubi, lived in an apartment for two years, naked, subsisting on winnings from online sweepstakes. He knew he was being filmed but not the extent. The image is from the final episode, the moment of the big reveal: he is shown that the apartment was in fact a television studio and raises his hand in shock. The context is the most interesting thing about this work and it’s unfortunate that there’s no way into it without reading the catalogue text.

Two artists, Antoinette J Citizen and Michael Candy, make use of live-feed surveillance technologies. Citizen’s work, Method for Mapping (2016), is an inkjet printer that produces a tiny line of colour every minute in a continuous, brightly-striped printout. Ostensibly the colour relates to the artist’s mood or environment at the time, but this ambiguous data is impossible to interpret. The piece points to social media sites that attempt to track and market our moods and emotions based on the words, clicks and emoji we feed into them. However, this work suffers from its proximity to Michael Candy’s Digital Empathy Device (2016). Beside a piece about large-scale tragedy, Citizen’s work — though technically complex — can come across as mere naval-gazing.

Digital Empathy Device is a highly resolved work, the strongest in the exhibition. Its physical form is a chrome head, crowned with wires, two syringes of tears and a tiny motor. A minuscule tube travels from each syringe, ending at the corner of each eye. On the next plinth is a cobbled-together device of wires and batteries, that looks suspicious but is apparently a mobile phone receptor. This is linked to an online, citizen-run service called LiveMap, which collates and disseminates live information about bombings and attacks in war zones around the world — in this case, Syria. When an attack is reported in the region, a phone-triggered signal causes the head to cry a single tear. An accompanying video shows the device being made in a hotel room and then attached to a Parisian statue which symbolises the French republic and égalité.

Because I’m there outside of opening hours, Dale is doing maintenance on Digital Empathy Device. ‘It’s not broken’, he explains, ‘it’s just been a busy month. It’s run out of tears.’

This takes a moment to sink in. The human brain is not capable of infinite empathy. After a certain point it shuts down. It has to. We may be postmodern but our brains are Stone Age, still only wired to interact closely with a small group of people. Eloquently, devastatingly, Digital Empathy Device speaks to this gap between reality and emotional response.

When the tears have been topped up, Liz, another director, offers to make it cry so I can see it in action. She takes out her phone and calls a number. The crown buzzes abruptly and a tear slithers down the polished face. Moments later, it buzzes again and a second tear rolls from the other eye.

I thank Liz. ‘Oh’, she says, ‘the second one wasn’t from me calling it. That one was real.’

I am standing in a lit-up room at the edge of a dark expanse under the ground, and somewhere in the world a bomb just exploded. The face of the statue is eyeless and cold. This one is real.