I saw the show Vital Bodies a few times. If I said I saw a painting, a pair of video stills, two installations and several text-as-art-practice works, would you feel bored, a bit excited, dismissive, a little covetous, or indifferent? Would you think it sounded like every second group show you’ve been to? If I was to tell you that a few weeks ago someone pointed to the Blue Oyster Art Project Space and said, ‘In there, the Idea is King’, or that a visitor came into the gallery recently and asked, ‘Is this a women’s gallery?’ would you change your idea of the show from the one you held five lines back and would this be different from your perception of the show when you saw the photographs, read its title, the name of the curator, the gallery and the town? Did you have an opinion then and do you have one now? Maybe not enough has happened yet for you to have an opinion but you will already have had at least one thought and maybe a sense of things. Opinion, which also means judgment, comes from sense or feeling but covers them over with evaluation. I’m pretty sure the French philosophers Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze are down on opinions. Deleuze and Guattari want to transform opinions into critical relations among ideas. Opinions, they say, have more to do with the cheese you like or don’t like than with thinking critically in the world. I think they use the example of German cheese. Deleuze and Guattari do not say it’s bad to like or not like something—that would be oxymoronic—but they are questioning the tension between individual preference and universal validity and want to move away from it. I’ve been considering the art works in Vital Bodies for almost three weeks now and I still don’t have an opinion but my sense is that some of the things (objects become objects by being finished but ‘things are never finished’)1 in the show share a quality that took me a while to recognise but which feels something like sincerity.

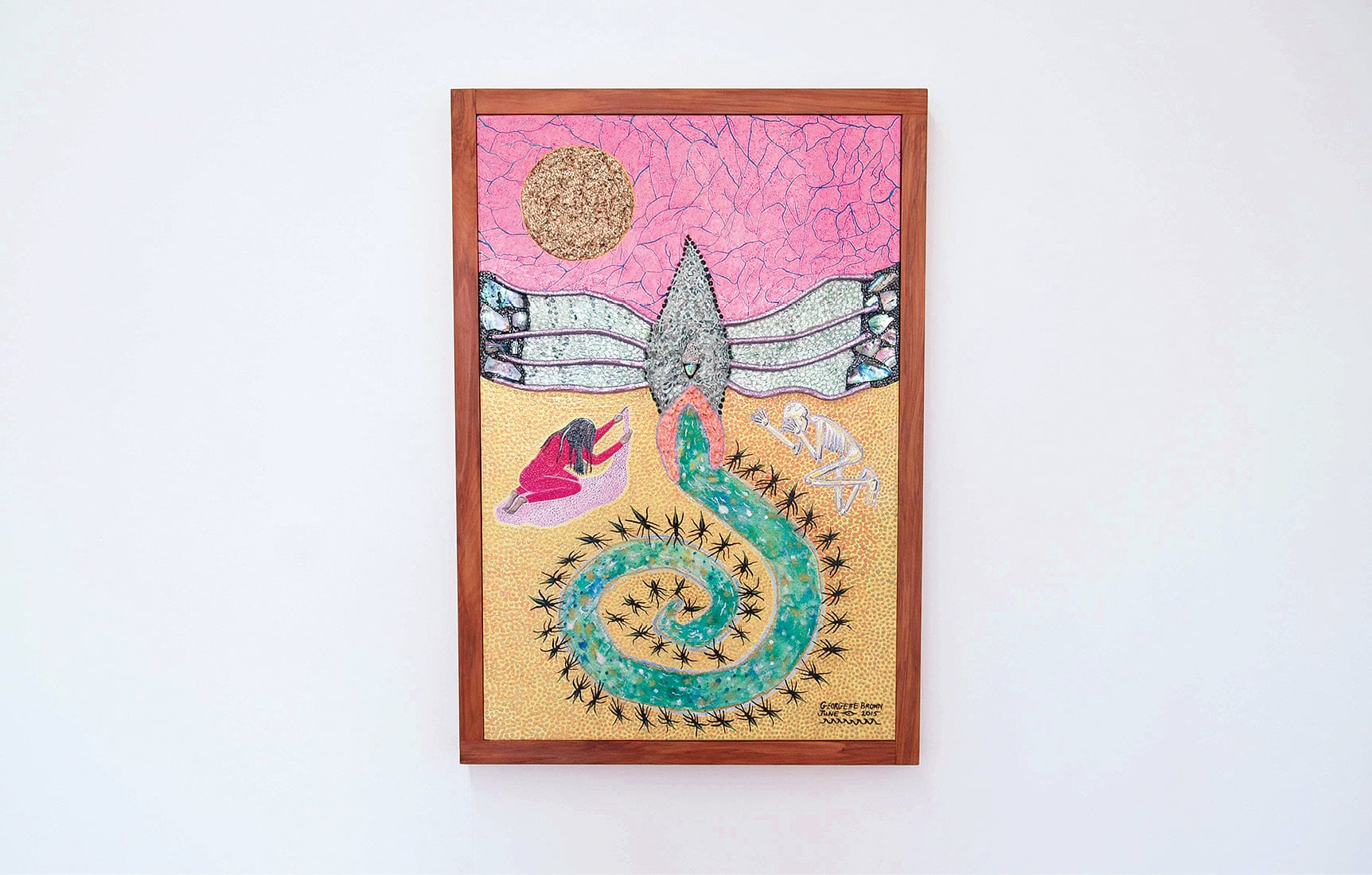

The show is also partly about vagina. Vagina is not a theme but it is a thing that turns up in Georgette Brown’s painting Painfully aware at the moment of salvation (2015). There’s a vagina and a uterus with their own moon/egg in vibrating patterns of pastels and texture—a small piece of paua (mother of pearl) is a clitoris and the fallopian tubes are made of puff pens. The painting is an exuberant cross between a religious icon and a colouring-in book. I felt a rush of blood to the head. The iconography of the vagina is also pretty apparent in Sam Norton’s Untitled (20th April 2015). In the second of two grainy video stills Norton’s hand stretches from the floor to insert itself into the crevice between the leather cushions of a sofa. In the first shot Norton is blow-drying her hair but not really. Norton is pretending that she’s pretending to be in an advert for great looking hair in the way you might use a hairbrush to sing a rock song or a tennis racket for a guitar and take a selfie. This is a hyperbolic narcissistic situation: ‘personal narcissism becomes an attempted escape from the limits of the individual’.2 Because it involves a vagina it’s also a euphemism for masturbation. In one of the text works in the show, a vagina is not so much portrayed as implied, well, more or less. Anna Rankin’s Get born again (2014–2015), a poetic text printed on three large photographs of the seashore describes ‘a giant gaping wound / fill it / it’s a typical girl wound’. The work reminds you that what matters about art usually lives outside it. It could be describing self-cutting but it’s also a vagina. The poem is internal, circular and without scaffolding. Standing in front of the poetry for what feels like a long time it’s difficult not to want to move away.

I think the show is partially about a vagina because someone told me there was a vagina in the show—the word is not so nice and I feel not so nice saying it. If I had a friend called Vagina would I think that it isn’t a good name? No, because she’d have a face. What’s wrong with the word vagina? Would you trade vagina for cunt, the 1970s for the 1990s, Judy Chicago for Tracey Emin? Would the artists in the show? Which one is the most sincere? Vagina is not ‘excitingly multiple’, doesn’t have the ‘punchy frankness’ of cunt, ‘the still-thrilling buzz of the just not-said’.3 I’m afraid I’m not up to date. I desire being up to date. I belong to a certain level of discourse. I am not sure if it is the same one as yours. I’m not sure if it’s the same one as the one(s) in Vital Bodies.

The hole Wendelien Bakker digs in her back garden in Swimming Pool (2014–15) to build a functioning swimming pool could be vaginal but only at a stretch. Watson explained that Bakker’s swimming pool is a feat of endurance.4 The photographs of this feat are on the gallery web page while in the gallery there was only the poetic text in three piles of the numbered steps 1 to 38 it took to make the pool. There are many precedents for list poetry or poetry that becomes a list but they don’t tend to accompany the thing done, the doing of the things listed.5 The feat and the poem are what I want to advertise.

5. I dug for two months. When it rained I had to bail the water out with an old bowl. … 9. I walked all the bricks home that I could find. Mostly carrying them in my jacket in front of me. … 23. I called SSL on the Northshore line. I ordered pool plaster.

I’m building up a picture for you; it’s more atmospheric than visual. So far there is Brown’s exuberant painting, Norton’s hyperbolic self-portraits, Rankin’s textual intensification and Bakker’s endurance. Can you feel the mood accumulating?

I read somewhere that artists don’t need others to write for them because they articulate themselves in their art and in writing all by themselves. Accordingly, I only need to mention the artists’ names and their works and leave it at that. The coins in Virginia Overell’s Explaining roads, a town, a distant lake (2012–2015) don’t suggest a vagina at all but show the gradual process of the coins’ defacement from a mixture of hydrated lime, salt and water. Holly Child’s House sitting at Kerry Ann’s (2014) text doesn’t have a vagina but the enlarged excerpt of a story from a computer screen uses emoji for things like Marj Simpson’s blue nipples. Check out Child’s novels No Limit and Danklands. Her writing can be fun but it can also get pretty serious. House sitting at Kerry Ann’s also describes the depressing future of the South Dunedin, a lowland suburb that floods every year and will eventually disappear beneath water, losing its face, eroding like Overell’s coins. Child’s cute emoji tell a story of death which Overell’s coins in temporal transformation take to the other side where life continues. There is no irony here.

There is no neutrality (in art, in Vital Bodies). Overell says we still recognise the coin as a coin even when it is no longer a coin, even when it has no signs of currency, even when it has no face, because the coin is a symbol.^6 Similarly, we recognise the vagina in Brown’s painting even when it’s an extended play of what is technically a vulva. If you had a friend called Vulva, what would you think? Is it any better?

There is no objectivity (in art, in Vital Bodies). Because the works are sincere in a 2015 kind of way, I saw barely any eye rolling and heard hardly any yawns of intolerance towards its ebullient deployment of everyday feminism. Despite this consternation, and complaints that the show is naïve, too simple, too sincere and anachronistic (too much vagina?), the show doesn’t budge, it doesn’t even wobble but skims the surface of criticism. Watson likes the anthropologist Kathleen Stewart who writes about living ‘on the surface tension of some kind of liquid. Seduced by the sense of an incipient vitality lodged in things, but keeping oneself afloat, too.’7 I don’t know if I’d call these works and their artists what is known as the new sinceritists or associate the show with David Foster Wallace’s ‘anti-rebel rebels’ but on the surface Vital Bodies does risk accusations of sentimentality, of melodrama, of overcredulity and of softness. In other words, the show contains ‘a willingness’ to be both ‘suckered’ and judged by a world of opinion.8

Catherine Dale teaches at the University of Otago in the English literature and Gender Studies programmes. She is involved in and consults for grassroots organisations in New Zealand such as transitory artist run spaces and temporary art, poetry and literary events.

Notes