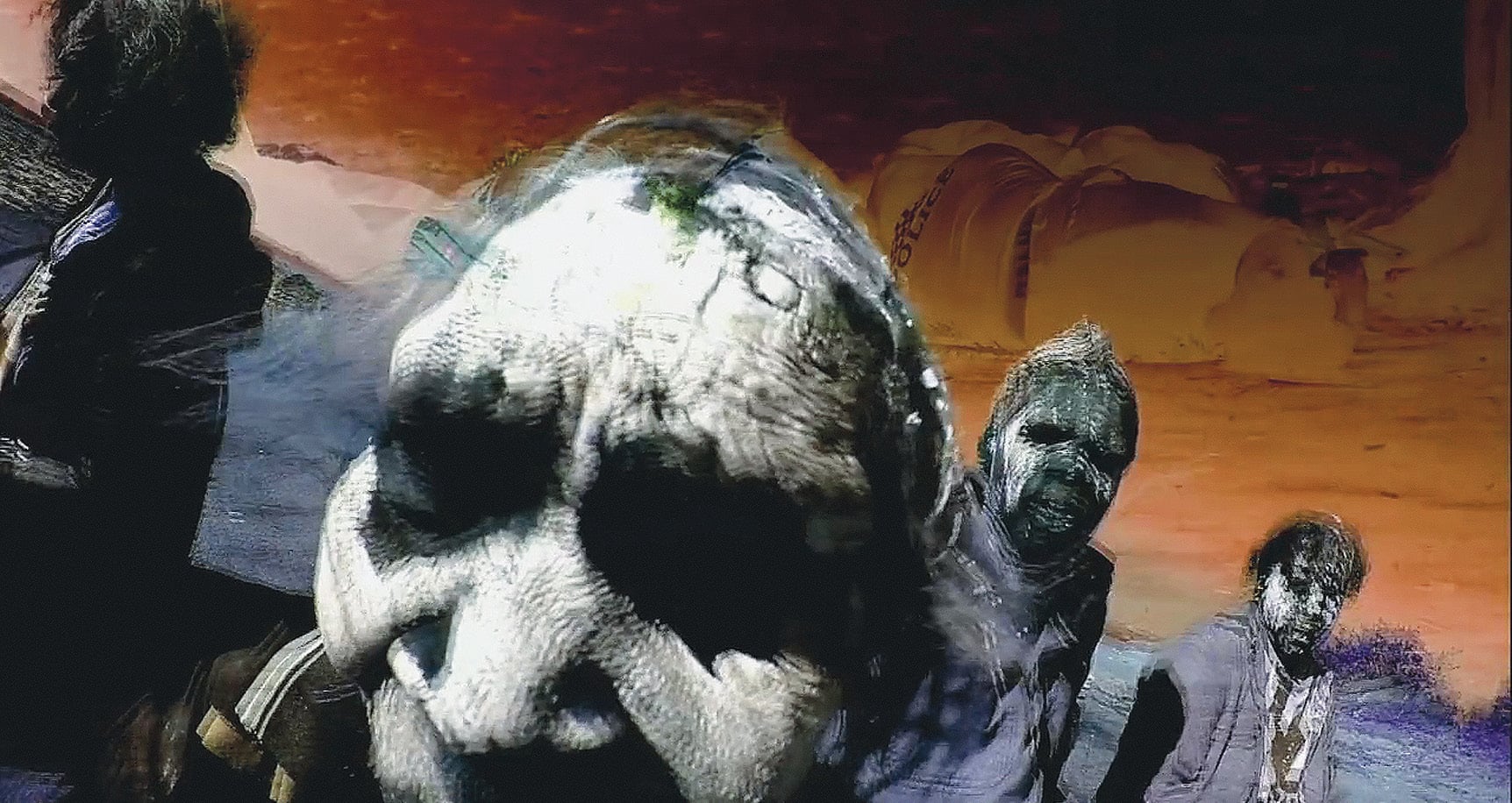

Drawing from questions written with Adelle Mills and Pip Wallis, I met a few members of the Karrabing Film Collective (Linda Yarrowin, Rex Edmunds, Natasha Lewis, Gavin Bianamu, Elizabeth Povinelli and their friend, Susan Edmunds) during their time in Melbourne, in August. The collective were showing two short films at the Melbourne International Film Festival: When The Dogs Talked (previously screened at Gertrude Contemporary, in December 2014, and winner of the Cinema Nova Award for Best Fiction Short Film) and the more recent Windjarrameru, The Stealing Cnt$*.

The focus of our questions, Windjarrameru continued the ‘improvisational realism’ of the first, blending fictional and documentary styles to tell a story of a gang of boys who miraculously find two cartons of beer in a poisoned area of the bush. Or so they thought — and from this ambiguity, complex and urgent questions around corruption, communication and racism are raised.

You probably all have a different answer to this, but who are the stealing cunts in Windjarrameru, The Stealing Cnt$*?

I am, I’m one of the gang members.

[LAUGHS]

The miners.

The whole lot—Trevor and Nungarelli [two associates of the miners, seemingly engaged in corrupt practices] too? Or just the boss miners?

The whole lot of them are involved.

I think just the two miners, personally.

Yeah. I think that the miners must be setting up the other two, to go down and paint there, take the blame.

I agree. I think Trevor and Nungarelli are just trying to pay off their fines. They’re just taking the blame if something goes wrong. Maybe we could also just tell him about fines? You know, how fines work at Belyuen, or wherever?

Yeah fines… if you get fined you have got to go to court. They put a search warrant out.

And if you don’t pay your fine off, your money keeps building up and up.

And for one open can of beer, how much is that?

$180 I think.

Whoa.

Yes! Now you want to know about traps! One can! What about—what’s that thing called… ‘disturbing the peace’? Party-party. They fine us for that?

They give you a warning. Or else they give you a fine, because of neighbours complaining.

So the police are the stealing cunts as well?

Yeah, I reckon.

Are they on our side, the police?

No.

Not in the movie, just in the regular life?

Certain police. You got Indigenous ones, you got European ones. Some Europeans are good, some aren’t, some Indigenous ones are good, some are not.

Yeah that’s right. But just in terms of fines, the other day Leanne’s husband Josh was driving at night, just to get some groceries. It’s about 15 km to the shop, and he got pulled over. It’s about an $800 dollar fine for an unregistered car. How much is a paycheck every two weeks? But how much does your [to Gavin] father make every fortnight? How much comes back?

$200.

So there is a massive difference between the fines and what people can actually pay or afford.

Yeah exactly, and that’s why they build up. And if you don’t pay… prison.

Enter Sandman.

Yeah, yeah. But you know, why does that mob, the police, why do they keep fining us? You would just say it’s their job, but…

I reckon they’ve got nothing better do. That’s it.

They’re just spending their time going back and forth from Darwin, fining everybody.

Yeah, they should just be in Darwin, and leave us alone in the community.

Well in the film, the police try and arrest the boys who have been drinking in a poisoned area, and I wondered if you could talk about that poison area—there is actual asbestos poisoning there, right?

Yeah.

So that’s part of it, but it seems it could mean many more things. What does poison mean for you? Why did you decide to set the film in a poison area?

Well, we’ve got Dreaming sites, where there’s mining. Mining usually goes ahead. They don’t really care, they just go across our sacred site, Dreaming site. Wreck the whole thing and then all they get is a slap on the hand.

They don’t get sick.

Sick, yeah, who gets sick? Who gets sick.

So poison comes to mean restriction or exclusion, in the sense that when a mining company decides to take over a certain area, you are restricted from that area, regardless of whether or not they are using poison.

Yeah that’s right. Or even with that fence, remember? You know at Bwudjut? Anyway, we go under the real fence, and we go into the real asbestos area. [Laughs] We did a shoot at Midjili which is surrounded by an asbestos area and the police caught us. But we’d been camping and hunting their for decades and no one cared to clean it up or stop people until after a land claim had been settled and white people were slated to state moving in. Don’t look at me, we were fine!

From years ago, when you [Elizabeth] were first at Belyuen, the mining companies would mine the land, and pay part of the profit to the Northern Land Council (set up under the Land Rights Act, 1976, to manage Aboriginal land on behalf of the traditional owners).

But is it illegal?

Well, it’s legal…

I wondered if we could now talk about all the different times going on in the film, and why you decided to join them all together. For instance, there’s the start with the ABC recording from 1948, the narrative is completed over a day, and then there is the sacred time of the nyudj, which are the spirits. Are they the soldiers? Do they relate to that?

They’re ancestors that passed away in our country, their spirits are there. If you walk there, you sort of can feel, not feel, but you sort of have nerves… they are around. They don’t harm you. They help you, and they are happy that you are on the country, if you are walking around there.

You can feel their presence.

And are they the spirits that you see when night happens in the film, and the boys are in the poison country?

Yeah, at night, and sometimes [at] daytime. In the movie, you see them at night, they come out.

Sometimes play tricks on you.

They can make your car break down, or your boat. You haven’t gone to that country for a long time, you can get punished.

So it’s not a different time. It’s the same time. It’s not like ‘dead and gone’ it’s still there. And that little conversation that Cameron has [in the film, about Aboriginal soldiers in World War II]… there was a war camp there. A lot of Aboriginal people were there, family. They used to have this thing called ‘Black Watch’.

What’s that?

They called that soldier mob ‘Black Watch’…

[Black Watch would] protect the navy ships, the submarines, fighter planes… showing them the coastline, patrolling that area, in World War II.

What about the recording at the start? How did you come across that?

That recording was from a 1948 ABC show called Walkabout. Walkabout came to Delissaville…

Delissaville is Belyuen, before it was called Belyuen.

Exactly. Delissaville. Mr Delissa. After land rights, they changed it to Belyuen. So ABC Walkabout went to Delissaville and they recorded, what we call kapuk…

…burning the rag (the clothes of the deceased).

Yeah, and John Moreen’s mother was in that thing, they refer to her, Bilawag, and to Mosec, and Bianamurrg. The broadcast was full of relatives. And it’s really long, and it’s like unbelievably, like… weird. It’s like white people talking about Indigenous [people]… you know how they were in the 1950s? Like really half-no-good, or totally-no-good, I don’t know how to put it.

Anyway, another time thing: once we were giving an interview at Charles Darwin University, and they [the interviewers] said, ‘Dreaming keeps going’ right, but then Gavin said, well, ‘Racism keeps going too’. Like, never-ending story.

And I guess that never-ending story happens in the film too, when the police arrest the boys—they have no hope. The character of Cameron is really interesting in this way, because even though he didn’t do anything wrong, his future has already been determined regardless. I guess that was something that you wanted to put together with all these different times, like the clip from 1948, giving a sense of an ongoing time…

There was that one scene we shot, that hallucination one, when they’re upside down running and Gavin is hallucinating. Well we shot that scene [as if we were] back in 1948; where these army men were chasing the same boys getting chased in 2015, [laughs] and that last scene is in the future, where still the same four boys are running around [laughing] chased by the cops!

It’s horrible!

Yeah! Now you get! From 1948, to 2015, to 2080, the same boys are going to be running around, chased by cops! [Laughing]

So, in that scene, some of the boys get the horrors? What happens when you get the horrors?

You don’t know what’s going to happen to you. You’re going insane. [Laughs]

[Laughing] That’s one way to put it! When you see a person having the horrors, you just say to that person, ‘yeah yeah… yeah yeah…’ They are just seeing things… you don’t know why, maybe they’ve drunk too much, maybe they’re on drugs, maybe somebody did something to their head, could be munggul…

Like a witch doctor. Or could be like spirits… spirits from our ancestors. Could be one of the stealing boys…

Yeah, we don’t know. In the movie it could be the ancestors, could be the [poisoned] flagon bottle, could be all of it, we don’t even know. Just too much.

Or even the fact that [the boys] have given up, they can’t live in the bush and the police are waiting, there’s no way out. There’s that line, ‘Jail is better than horrors in the bush.’

There is no way out.

That’s also interesting with time, the horrors and time. Because, in the movie, is it the future, or is it the horrors? The film says that they’re the same.

But that’s because it is the same, no matter if it is 1948, or 2015, 2080, it’s always going to be those same boys being chased by the same cops.

Yeah, but you wouldn’t say that, unless you wanted to say ‘no’ to that.

We do want to say ‘no’ to it—making the film is one of the ways we’d like to say ‘no’ to it.

This might then be a good time to ask about traps. There is a memorable line in the film when one of the characters, who has just been asked to help the confused, white, Legal Aid worker understand the complicated situation, says simply ‘It’s a trap.’ There is also an interesting part of the film, where one of the boys says to Trevor and Nungarelli, the men painting on the rock, that they’re myall

When The Dogs Talked…

myall

When The Dogs Talked is like, you’re dumb, you don’t know anything…

Useless?

Not useless, not just useless. It means you got no understanding of white people. It’s about white people. You could also be myall

When The Dogs Talked for black culture, meaning you’ve got not a clue about it. You don’t know top to bottom or which way to go. If you’re myall

When The Dogs Talked for white culture, you think ‘what is this thing? Is it a shoe or a hat?’ You try and put a shoe on your head.

So you call the men myall

When The Dogs Talked, why?

When the miners said, ‘We’re going to call the cops’, and I said, ‘Eff you, you myall

When The Dogs Talked blackfella, go on call the cops’, and all that…They don’t get what is happening to them. How they are being used.

And why did that fly out of your mouth? Because my directing was, you know, you’re ashamed of your dad [Trevor]—you’re looking at them, and they’re doing this thing to pay off their fines…

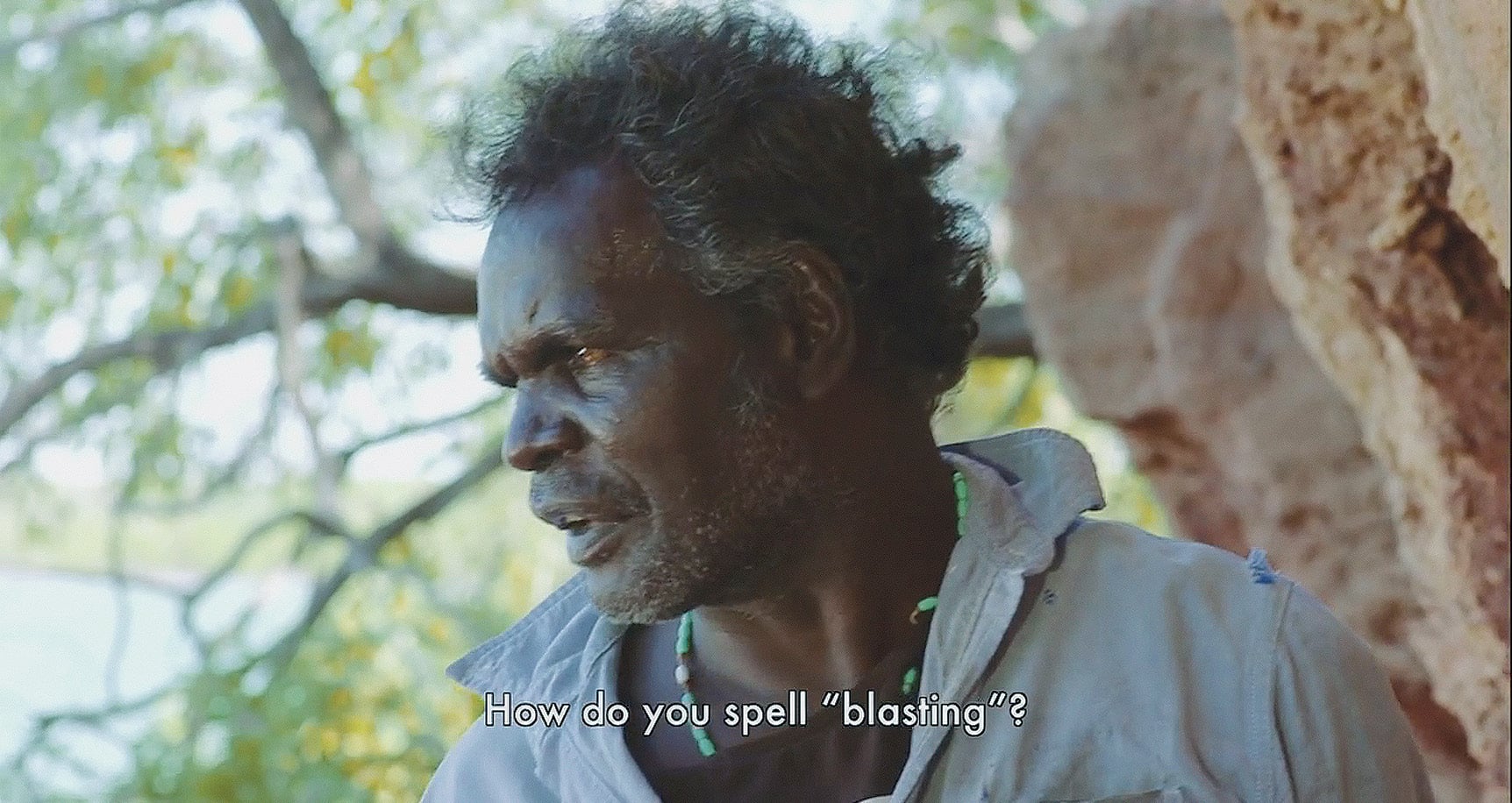

So what are they doing? It seems unclear… they’re painting ‘BLAST’—are they trying to let the miners mine there by painting ‘BLAST’ or are they trying to protect it?

Oh… that’s interesting

They’re saying you can’t mine there because this is a sacred site, and that’s what they’re marking, ‘NO BLASTING’.

Oh really? I thought they were saying, ‘BLASTING AREA, DON’T COME HERE’, for fishermen. They’re working for the miners. What do you think, Rex?

Yeah, that’s what they’re doing there. They were the two dumb ones, so we, the two boss miners put them there. Put them in a trap.

Yeah, a trap!

Yeah, we thought the miners left the alcohol there, and made a trap for the boys, that’s why we got in trouble. They wanted us to get in trouble.

To shift the attention.

What is also interesting is that in the film, the miners and the police are Aboriginal as well, they even seem to be a part of the community maybe? It is interesting the way that works…

Well, we don’t have many white people in the group! [Laughing] I had to be the ‘Racist Jack’ in our new movie and I didn’t like that at all! They were all pointing, ‘You’re white, you can be that role.’ ‘I don’t want to be that role’, I said. They forced me to!

It is confusing though. Is it because you guys didn’t have any money to hire white actors, or you didn’t want to hire white actors? As a white viewer, when you see Aboriginal miners, it’s hard to know whether it’s on purpose you did that, or because you have to.

Ah well, what to do about that? So it is confusing, but that’s the way it is. It makes the movie interesting. It’s just like…

No I’m not criticising it, but it’s interesting, because, for me, part of what the movie is about is how do you even make a movie with no money?

It’s true!

So yeah but… I think that Rex Sing and Rex Edmunds, they just nailed that role [of being the miners]. I thought, I don’t want any one else, because we really know those people, we can play them better than they can play themselves.

But then, I’m thinking of When The Dogs Talked and how one of the things the film’s about is what you are forced to do to keep your house, or your job, and how this makes it difficult to do other important things like visiting and protecting Dreaming sites. It seems that the miners are like that, they need a job—they want to buy their boat—but they have to mine their country in order to do that. Is that split a struggle you always have?

Always been a struggle.

I’ll tell you the truth, even to come here [to Melbourne], the first time we went to Gertrude, we were told—someone told someone—that if they went, he would sack him.

A boss told someone?

Yeah, the white boss.

Go look for another job they say, and there are no other jobs. So you know, we all stand up, they come around, they back off, it’s like bully-bully. That’s all.

They want so see how much they can do, just by scaring you…

One last thing, I wondered about what ‘no signal’ means for the collective, and how in your films characters are constantly hunting for reception—driving out on a bush road with a phone held out of the window, or standing precariously on a fence… I was thinking that perhaps your films are trying to start a different kind of signal, to send different information out there… is that how you think about it?

Yeah, our own little message.

You’re trying to find someone who can hear.

Yeah

Yeah, who can hear it…? You reckon anybody listens to Indigenous people? The government… like really? They care? I’m sometimes thinking, we’re just standing there, before this going, ‘Hello, hello? Anybody listening?’ Anybody listen when your mob been homeless [after a riot in Belyuen, in 2007]?

Not really. To tell you the truth some people just care about themselves. We tried many ways you know, talking to the media, talking to different people, government people…

No answer.

You’ve said before that the time when you decided to make films was after the 2007 riot at Belyuen, so I guess it comes from that in a way, trying to send that message and get people to listen to you…

Yeah, get people to listen more. We had to just do something about it, you know, make a film about it, so we can get somewhere, so that they can think these are the people who’ve been homeless and this is what they have been through in life.

First, we tried to rely on other people, but then, who did we rely on?

Everyone.

Yeah, then we relied on ourselves. Generate our own battery.

The Karrabing Film Collective is a grassroots Indigenous based media group most of whose members currently live at Belyuen in the Top End of the Northern Territory.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli is Franz Boas Professor of Anthropology and Gender Studies at Columbia University.

Aodhan Madden is an artist, writer and a sub-editor of un Magazine volume 9.