I am selfish and so is everyone else under capitalism who can afford an iPhone. Men like to talk about surveillance as if it is the state. Women take photos of themselves. A famous woman selling herself is the archetype of us all. Selfish, Kim Kardashian West’s book of selfies taken over her lifetime, induces vertigo because a woman’s archive is always abject. Even one person’s selfie finds it hard to relate to another person’s selfie, that’s why relationships are so hard under capitalism! The use values of two bodies and the relation between two are separated forever by their exchange value and the relation between one and many. This is not only in the relationship between a woman and a man. Tragic romance multiplies and extends out. I go out to dinner with my friends, one on one, us against the world. This is love in but against the couple form,1 where one becomes two.

Although Narcissus, looking forever into the technology of a reflective puddle, is a young boy, it is the young girl who really needs to take selfies, her self so tightly constructed by her image. This need is not the girl’s own invention, however, she inherits this mode of being from the patriarchy. Luce Irigaray writes ‘Man endows the commodities he produces with a narcissism that blurs the seriousness of utility, of use. Desire, as soon as there is exchange, “perverts” need. But that perversion will be attributed to commodities and to their alleged relations.’2 It is the girl taking the selfie that is not taken seriously, instead of the guys who invented the technology. Everyone needs help coming to terms with being a commodity regardless of gender, but it is the feminine that is progressing further into abstraction and emptying out of blood. It is hard to imagine a book of selfies devoted to anyone other than a woman, the fulfilment of both the ideal consumer and commodity, eating itself like a snake. But this is also why it is so abject. The academic, like the start-up bro, would say that the archive should never be in the hands of its object of study.

I read Selfish hung-over, eating ice cream. I felt nauseous, too stimulated by the flow and repetition of images. Kim recently endorsed a morning sickness drug. As celebrities start communicating to their fans directly on social media we learn that celebrities just like the masses can think for themselves. A celebrity may be complicit in the pharmaceutical-industrial complex but that does not mean she is ‘evil’ any more than the consumer of her brand is ‘dumb’. Although we should aim at abolishing capitalism and gender, we would do better to listen to those who are wedded to these categories, than the people who feel like they can live without them. Kim’s neoliberalism seems in conflict with what I love about her cultural output, her work on the relation between fantasy and reality. Yet that does not mean I simply reject this feminist, cultural labour. Calling out sometimes works with the structures of oppression and the law at face value. At its most powerful it also enacts the small gestures of relation that we use to negotiate within these structures. Everyone is complicit, there is no ethical consumption or reproduction under capitalism. Everyone is complicit, however, in their own negotiation of this fact. Some of Kim’s fans rejected her recent involvement in the pharmaceutical industry and maybe she will listen to them, but probably not.

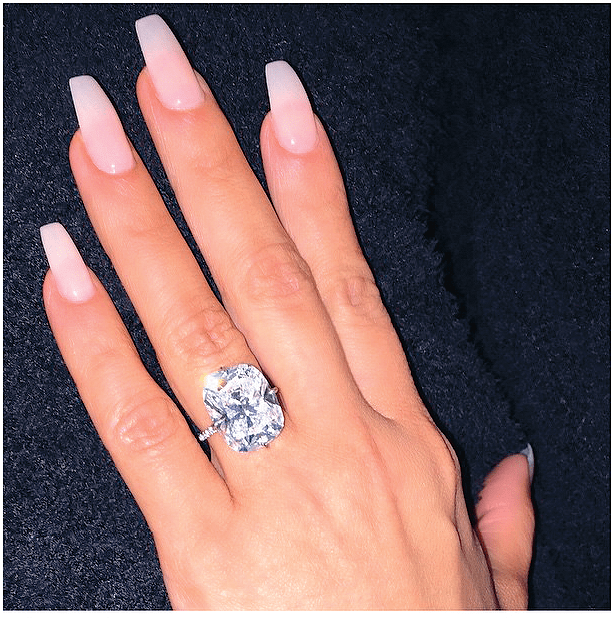

But how does a commodity listen? It depends how much you attribute subject status to what is traditionally seen as an object. Irigaray reads Karl Marx’s chapter ‘Commodities’ in Capital and replaces nouns such as linen, corn, and diamonds, with ‘woman’.^3 Plant and mineral materials are transformed into commodities with use value, for example the flax plant is made into linen that is then sewn into a jacket, a new commodity with a new use value. Use value divorced from its exchange value that goes up and down depending on how much labour a commodity requires in relation to other commodities, for example cotton requires less labour than linen and is therefore cheaper. The use value of woman, her own desire and body, is divorced from her exchange value, constituted by the desire of men who determine the value of women in relation to other women. The exchange value is again determined by the amount of labour needed to produce the product. A woman who works out and does her make-up every day is worth more than a woman who sits around writing in her pyjamas. Diamonds, which are rare on the earth’s surface, and therefore require lots of labour to find and then mine, are given to the women who labour the most on their appearance. This feminine labour is not hard work that pays off however, it is usually the maintenance of inherited wealth and genetics while Cinderella works three casual jobs. A commodity cannot speak or listen. Traditionally the celebrity seems closest to a diamond, a rare commodity to be consumed as tragedies of their ‘real life’ disrupt their aura and therefore become separate commodities fetishised along a different line of desire. More and more, however, celebrities, like women, are beginning to speak, taking control of their own surveillance on social media.

I did not grow up taking photos of myself every day. As I entered puberty, bleaching my hair had similar significance to burning smiley faces on my leg with deodorant spray cans. These were activities I never did alone, only with my girlfriends. And when we did photo shoots we did not style ourselves or put on make-up, expecting the ‘glamour’ to arrive in the photo itself: that was the camera’s job, right? As I got older and more single I started a little bit to recognise the connection of labour to image. My exchange value in high school and then university was all about moisturised, shaved, tanned legs. Although they were for ‘man’, that is myself and the world, to look at, it also felt nice when I sat next to my friends. The couple form is the strongest between young girls because this coming together is based on sameness, not difference, where intensity meets intensity. We were not exchanged among men but rather produced our own economy. I first fell in love with my best friend when I was fourteen. Boys were things to talk about, one part of the world we were discovering together. Like any couple, however, this happiness was an island. The exchange value of the girls in the class went up and down the hierarchy, as deals made with powerful girls and older boys disrupted our world. The point is though, often our relationship did not feel like a country but the water around it. This is the immense joy of the single girl unconditionally coupled to another single girl.

The love in this kind of couple, like any other, comes from a desiring body towards another. It is a strange feeling to have a sexual desire unrequited but the love strong as ever, the opposite of when boys dump you. It is still tragic however. What feels like a new economy to one is only a new currency for the other, a brief amelioration of the debt to our fathers. This happened to me the second time I fell in love with my best friend. Everyone said it would be a stage and therefore so it was. But what would have happened if they said it was the beginning of something? It felt like a new economy to me, but she had a boyfriend and I was not brave enough to find another girl. I was in love. Irigaray identifies the lesbian as figure that gestures towards a new economy. This economy is neither a relation between men and women (commodities) or the relation between women (commodities) defined by men, but begins at the question of ‘what if these commodities refused to go to market?’4 They might create a new economy where ‘use and exchange would be indistinguishable’.5 A new currency, rather than an economy, however, is only a new system of money used in only one country, the island of the couple. The vibrator of that relationship was replaced with a series of guys. I remained within the phallic economy: women without men are outside teleology, they have no purpose.

Love as telos, and the couple as the means to get it, is the strongest myth sold to the consumer. This is because the wife is the original commodity, marriage one of the primary oppressions that allowed for the development of capitalism. The private sphere of unpaid work holds up the public sphere and the production of value and capital. Marriage is the original name for the exchange of women; now we often talk about the ‘couple’, the golden ticket out of alienation. The couple form should be abolished in as much as the exchange of women should be abolished. But to focus on the couple instead of the one, the patriarch, the capitalist, seems to throw the loving relations, the feminine labour before it is labour, out with the policeman, the president, or the husband. Babies and baths are not the problem. The couple form should be abolished, but this form is not the form of two, but one: man. I do not have a bath where I live at the moment, but if I did I would have one every night. Love has been co-opted by capitalism the most because it is what we need the most.

Kim’s marriage to Kanye is the happy ending of Selfish, with photos of their hands wearing wedding rings, their marble wedding table engraved with ‘Mr and Mrs Kardashian West’ in gold. Kim’s marriage takes the forefront, in the book, as the relationships with her sisters and friends recede into the background. She ceases to be a daughter and becomes a wife: property is exchanged between father and husband. There are various progressive variations of this, and alternative ways of relation, however those who play out this symbolic order, those who become symbols themselves, are illustrative of the law to which everyone is subjected. Kim’s practices of make-up, plastic surgery and fashion constitute expertise in becoming a commodity, an expression of ekstasis; as ‘the commodity is disinvested of its body and reclothed in a form that makes it suitable for exchange among men’.6 Sight is the pre-eminent mode of relation in the exchange of women in capitalism, so much that it shapes the other senses. The Calabasas, valley girl accent is closed off, authoritative, matching the made-up face. ‘K’, ‘I love you’, spoken with a low and croaky voice, become phrases that shut out the reality of things not being ok, or of not being loved. They are coping mechanisms and instruments of revolt. Watching Kourtney Kardashian relate to her partner, I learnt how to say ‘mmm kay’ to my boyfriend, to keep us on the surface. So often we start drowning in our own insecurities. I do not feel owned enough, or owned too much, he does not feel like an owner enough, or too much. I cry-speak, which takes a lot of time and energy, so it helps learning to say things like ‘mmm kay’.

Sometimes I cry to my boyfriend about not being able to write, and sometimes he will listen and give me confidence again. Kanye was one of the first to see Kim’s labour as labour, and this kind of labour as art. The concept of ‘Selfish’ and the title were both Kanye’s idea. That is not to say that Kanye’s denomination and creation of art, his blurring of high and low, does not attract criticism in the same way as Kim’s cultural output. Low is bad, but to relegate low to high is even more offensive to those already high up. When Kanye raps ‘I think I just fell in love with a porn star’, he challenges the assumption that to be loveable a woman needs to be sexually pure. This speaks to the contradiction women are placed in, to be either a mother, virgin, or prostitute. Irigaray outlines these three figures of the phallic economy before developing the theory of a desire between women that escapes this economy. Kim is at least superficially all of the first three categories, an everywoman we can admire. There is something admirable too, about Kanye’s choice: to build a woman up who usually gets trashed. The mother, virgin, and prostitute are three versions of the commodity, three ways to exchange women, that ensure the circulation of capital. Within heterosexual relationships it can be nice if the man understands these impossible divisions and supports the expressions of femininity that do not uphold only one category. The acknowledgement of low and feminine cultures as something more than ‘silly’ encourages the development of creative processes of negotiation.

It is hard to talk about the couple without talking about the power couple. This is because the couple, the passage into the social and public sphere, is power. But to try and talk about being in a couple is an emotional labour that is hard to match with theoretical labour. My recourse to the Kardashian Wests is like trying on a valley girl accent, it is a way of bearing the weight of relation. It is an imitation of a denial of the emotions and the unconscious. Denial is how the neurotic deals with the unconscious. An imitation of the neurotic can work as a denial of denial so that the symbols of the unconscious are openly manifested. Julia Kristeva writes in Powers of Horror: an essay on abjection describes this as the work of the abject, borderline patient—perhaps the narcissist?—whose symbols become aesthetic. There is something lower than low culture: not a new currency, but a new economy. Although this is what I want, how do I write about it without letting go of the structural conditions that deny this new economy? How do I write about use and exchange value being indistinguishable when these divisions shape the labour of my writing? How do I write about the revolution that has not yet come into being? I can write about my girlfriends meanwhile it is primarily my boyfriend who sustains me with his emotional labour.

The exchange value of the emotional labour of my boyfriend, however, exists in relation to the residue of marriage in the couple form. I am purchased with the traditional requirement of providing free labour without any return. So his labour can only ever be compensation. It is feminine labour that is without value in itself and is therefore invisible. Building men up, like hanging out the washing, if repeated enough, is depressing. No catalogue of labours adequately describes the feeling though, of female subjectivity. If I am too much, you are never enough. Talking in monetary terms however, is a good start. Wages for housework, founded in the seventies, asks for monetary compensation for labour that traditionally has no value in capitalism. In the new iPhone game Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, the player receives rewards for changing outfits, and taking opportunities to network. You are playing for a career and a love life and you can choose to flirt or network depending on who you are interacting with. This is not a new feminist economy. Bea Malsky writes on The New Inquiry that games like this ‘certainly offer no solutions. What they do offer is a first suggestion, incredible in its existence on a mass-market scale: to make affective labor count.’ Instead of a new economy as such these games allow us to think ‘critically about our fraught relationships with our work, and to playfully reimagine what might be’. When men watch football or play video games, women do not have to make snacks and pass them beers anymore, they can watch the Kardashian’s on TV or play them on their iPhones, playing making snacks and passing beers.

Kim’s work is interesting because it is from the beginning about making money. Her engagement with being a commodity does not propose critical distance, she is not an artist one step removed from her depictions of femininity, she makes money selling a brand of herself. Artists, too, sell their brands. But there is Kim and then there are all the women who do not get paid for their labour. W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) is inspired by the Wages for Housework campaign. In their online wo/manifesto they write: ‘We demand payment for making the world more interesting.’ Is this ‘interesting’ an expression of the abject, direct from the unconscious? Some art achieves this. I see this in the work I think is the most interesting: young women artists who use their face, body, and writing to produce work all the time, online and off. More than the male poets Kristeva writes about, these producers of themselves produce the abject, more abject because it is described using feminine language. This operation provides critical distance from its object of study while inhabiting this object of study: a personality split in two. I learn of their world, and therefore, for me, they make the world more interesting.

This split is less defined in Kim’s work, it does not provide new angle on the world but reiterates the status quo. What is important, here, is the new visibility of the labour that creates the ideal woman within this status quo. Make-up is her primary medium, its function in Selfish is ontological and archival, she writes: ‘I can look at any photo of myself and can tell who did my hair and makeup, where I was and who I was with.’ The images capture the intimacy of her relations, not only with her friends and family, but her make-up artists and hairdressers. Her love of feminine labour is shared with those that are paid to labour for her, as she recognises the value of their work. Her primary make-up artist and friend of many years Mario Dedivanovic features in the book. Photography is used to document her make-up, which signifies her relation to the world: ‘where I was and who I was with’. The camera is designed partly on the premise, like most technologies, of freezing the beauty of white women. It loves her, if love means purchase. Kim and Kanye’s love for each other, like every true love is never entirely co-opted by capital, however. Lying in bed, his black skin, forgotten in the racist design of the camera, recedes into the background night, and all we can make out is her eyes, her lips. Standing behind her in the bathroom face-on, Kanye looks like a shadow while her skin, sideways, is catching the light. Kim’s choice of mediums: photography and video perfectly capture her, as she designs herself to be captured by these technologies. This relation ends up producing, much like the valley girl dialect, something new, in its mimicry and repetition of the feminine ideal. Kanye is familiar with this process in his music, rapping about ‘new slaves’ with old words like ‘nigga’ and so he understands what Kim does.

These two celebrities are often disregarded because of their narcissism. But what if narcissism allows them to convey abject capitalist desires directly? We learn from their work that capitalism reproduces us to consume and produce. Consumption: buying clothes, cars, houses are necessary for the production of reality TV, rap music. Writing performs a second operation, as writers on twitter consume this celebrity culture and produce their own work out of this consumption. The latter is often unwaged work. Women and especially women of colour are better at twitter because they have had more practice in unwaged labour. Twitter and Instagram are liminal spaces, repositories of the unconscious. Desire is constituted around gold, god, the father and celebrities profit off their proximity to these ideals, while non-celebrities reproduce and circulate capital for free. The value of Kim’s engagement ring is equivalent to her value as a woman. The diamonds dug up from the ground are made from the blood of slaves and labourers through history like the blood of mothers who reproduce our societies. This history is the contingency of Kim’s marriage. Her ring is so beautiful it is disgusting. Unmarriagables are so trashy they shine bright.

Narcissism, like capital, is not the totality of the celebrity relationships I consume. It must be hard maintaining a relationship while you are famous, but it is hard for everyone. If the celebrity is the idol, the ideal subject in capitalism is the narcissist. The narcissist looking back at herself is in a relation of two already, so how does she become part of a couple? She learns from the archetype. Consuming Kim’s products, I reproduce modes of relation, styles of language, clothing, and makeup. Consuming feminist theory I reproduce modes of resistance. How can I be in a couple? Consuming celebrity, I expect my boyfriend to ask me to marry him. Consuming feminist call-out culture, I expect my boyfriend to abide the rules of a new economy, not yet come into being. These are the contradictions of modern love. Love under capitalism gets turned into babies and diamonds in relations of value to each other. Understanding this material ekstasis works towards its abolition. As much as they try, celebrities are not static images anymore. Their misrecognition of themselves as commodities occurs often and is broadcast immediately to the world. These moments are new relations to mimic, rather than the idol side of their split personality. As everything becomes labour, labour at least becomes more interesting. Feminine labour in particular, intimacy and emotional support, is the one necessary labour for a relationship of love, not to be paid for by one to herself, but be given freely between two and in abundance. Anyway, I pay to see a therapist and convinced my boyfriend to see one too.

Eva Birch is a writer, a PhD student at the University of Melbourne, and runs Feminist Theory Group.