Nicholas Mangan Notes from a Cretaceous World Published by The Narrows in association with Sutton Gallery, Melbourne, 2010 Hardcover, 88 pages, 115 × 217 mm, edition of 500

I remember lying on scratchy carpet as a kid, watching the Common-wealth Games on TV, and yelling with admiration as Nauru’s single athlete, a chubby teenage weightlifter, smashed his competition in the snatch and clean and jerk. Propelling my empathetic revelry was my shaky understanding of the fraught history of postcolonial Nauru: a subtext littered with scandalous exploitation, spending sprees on Lamborghinis and a dizzying collapse in fortune for the nation formerly known as Pleasant Island.

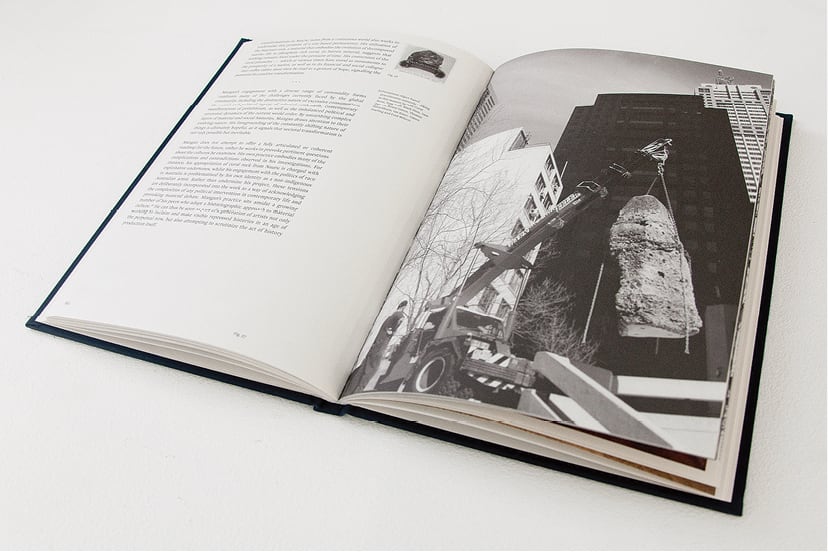

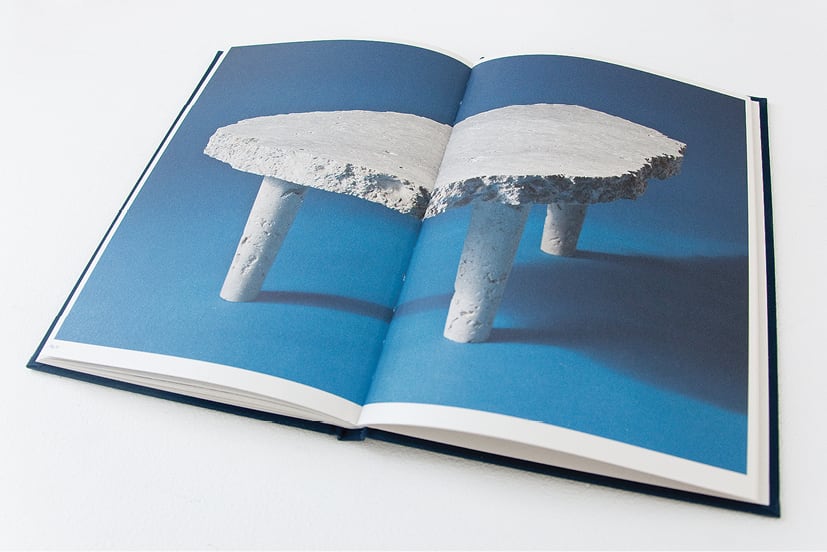

The tail end of Nick Mangan’s monograph Notes from a Cretaceous World traces this collapse through news clippings and a script reminiscent of Painlevé’s poetic-scientific cinema. Mangan recounts the 1970s construction in Melbourne of Nauru House, a fifty-two-storey skyscraper that asserted Nauru’s status as the second wealthiest country per capita in the world. Three large pinnacle rocks were installed at the entry as totemic swagger, flaunting Nauru’s phosphate riches. As the years passed, the phosphate was mined to exhaustion, Nauru sank into bankruptcy and its leaders resorted to selling passports to make ends meet. The government of Nauru was evicted from its namesake tower, and the blackened pinnacle rocks were torn from their pedestals. (Mangan subsequently located one of the deposed rocks and crafted it into coffee tables, materialising the presumably sarcastic proposal from Nauru’s former president Dowiyogo for a new moneymaking industry.)

Nauru’s rise and fall from capitalist grace is usually caricatured as a study in human folly and pathos. Mangan’s focus on the pinnacle rocks as terrestrial characters reduces the absurdity of human intervention on Nauru to a microscopic time slice in the island’s geologic evolution. In a double spread of images that opens the monograph, he includes a picture of a disembodied hand pointing to a tree ring, subtitled ‘This is where it happened’. The video stills that sit alongside Mangan’s script present depopulated scenes from Nauru: rusting vehicles, a rubber-stained tarmac, satellite dishes and bleached pinnacles. Despite the decay, the images mimic tropical holiday snapshots. Nauru’s blue skies are spotted with cumulus, clusters of palm trees frame concrete ruins, and rays of sun beam down upon a trapped bird. There is a sense of disaster tourism here: exotic corrosion and rot as the neo-colonial grand tour.

Shelley McSpedden’s text, which constitutes the bulk of the monograph, presents a rigorous, scholarly survey of Mangan’s practice, locating his artwork in the context of identity politics and postcolonial theory. Often, the rational argumentation that marks academic writing can act as a formal straightjacket, inhibiting the imaginative thinking that might be provoked by looser associations. Mangan offers a visual antidote, placing images of tangential relevance alongside McSpedden’s text. The black and white reproductions add to the sense that the cloth-bound monograph resembles a pre-1990s graduate thesis. One photograph shows an illegible plaque attached to a mounted piece of rock — apparently the original rock that launched Nauru’s phosphate discovery. Collected by a trader who thought it could be used to make children’s marbles, the rock was abandoned to life as a doorstop for several years before someone had the bright idea to test its chemical make-up. (An illustration of the rock-as-doorstop is also included in Mangan’s -image bank.)

Squinting at another photograph, tiny to the point of near obscurity, I can vaguely make out a group of posing tourists. A grinning man sports a hat with a leopard print band. Two women have painted their faces like kids at a community fair. The image is attributed to Dennis O’Rourke’s The Cannibal Tours, which Wikipedia informs me is a documentary about ecotourists cavorting through Papua New Guinea. As well as photographing ‘primitive’ customs, the tourists decorate their faces in ‘native fashion’ and dance around mimicking war cries. It seems to be the sort of film that prompts enlightened viewers to groan as graceless colonial relics play out the Pacific version of blackface pantomime. But what distinguishes Mangan’s aestheticisation of Nauru’s ruinous landscape from the happy snapping of the Cannibal tourists? And how does his enactment of Dowiyogo’s proposed rock-as-coffee-table differ from the tourists’ performances of native ceremonies? I posed these questions in an email to Nick. His response ran something like this:

It’s hard to escape aestheticisation through the lens. I am a tourist. I’m interested in the subjective-objective dilemma and the palm tree postcard trope. After all that has happened, the landscape of Nauru is still for sale, still bound to western capital for survival. The tables aren’t really coffee tables, they are more like oversized Petri dishes. Cutting through the rock reveals a time capsule. And slicing through the pinnacles echoes what has happened to Nauru. Through the process of strip-mining, its top has been chopped off. My depiction of Nauru is a work of fiction but Nauru’s history is stranger than fiction. It’s like a J G Ballard novel.

Fayen d’Evie is an emerging artist and writer with a lingering interest in the ethics of intercultural practice and the politics of distant concern.