The Memorial Coordinated by Claire Lambe and Elvis Richardson Death Be Kind, Melbourne 29 June – 25 July 2010

In The Poetics of Space (1958), Gaston Bachelard famously imbued the spatial tiers of a building — its cellar, bedrooms or roof — with a series of phenomenological and psychological connotations: the attic with intellectual contemplation and pleasant reminiscing, for instance, or the basement with feelings of fear or repression. Since its publication, these various characterisations have provided a formula for interpreting different dramatic personifications in literature, film and art. However, with the growing predilection for art spaces that architecturally set themselves apart from the ‘white cube’ model (i.e. PS1), these characterisations have been increasingly employed to help determine a methodological framework for interpreting exhibitions too. Death Be Kind, a newly established type of artist-run initiative, nestled upstairs above The Alderman bar in East Brunswick, can barely escape evoking such oneiric and Bachelard-inflected associations — particularly with its inaugural exhibition, The Memorial.

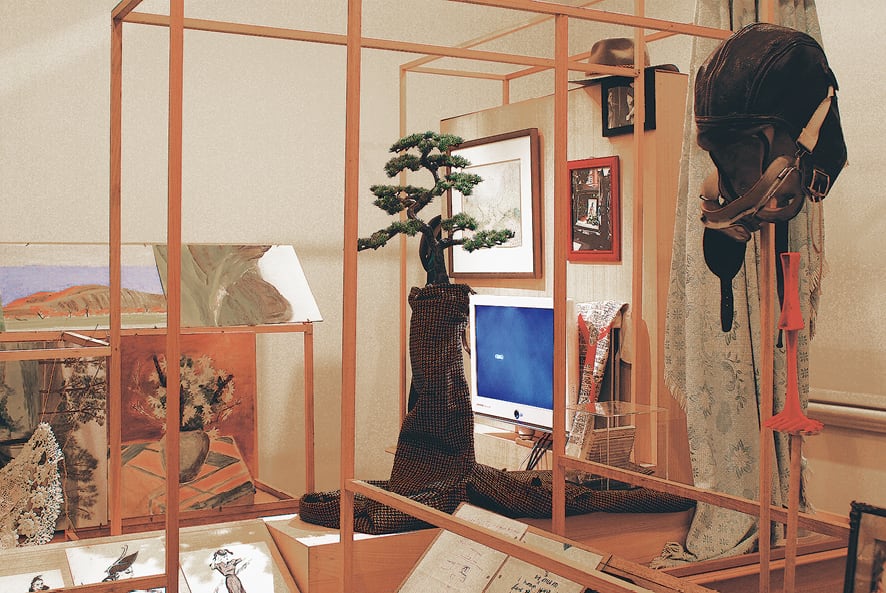

Coordinated by the gallery’s joint directors, Claire Lambe and Elvis Richardson, The Memorial presented a poetic and intimate social history of death. Lambe and Richardson asked over 100 people to lend an object that once belonged to a friend, partner, family member or acquaintance, then arranged the archive of inventoried objects in an elaborate and labyrinthine, hand-made wooden display case. Unlike the traditional vitrines that one might expect to see in European ethnographic museums of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, however, The Memorial’s cabinet lacked any glass or Perspex barriers cordoning-off the viewer from the mementos held within — I had to feed my hand through one corner to be sure. Furthermore, the keepsakes were arranged at variegated heights and their placement was not delimited by the cabinet’s adumbrative wooden perimeters: a pair of white, goat-hair boots jutted out from a vertical surface towards the back of the room, and a backpack was draped over the shoulder of a raised, stuffed jacket towards the front (its posture suggesting that it was watching over the other trinkets). The Wunderkammer-like collection of objects was open and — in many ways — orderless, reflecting the non-linear organisation of memory that is often triggered randomly or synaesthetically.

Moreover, the glassless mode of display was mildly destabilising, like the mental jump I made as my hand passed ‘through’ the imagined glass. The objects — which, granted, did include a bonsai tree — seemed to grow and emanate organically from their fixed positions, creating a virtual web of dialogues on remembrance. Bachelard wrote of the domestic environment that ‘[i]n its countless alveoli, space contains compressed time’.1 This transferral or transmutation of time into space is similarly extended to these treasured objects, into which their current owners have compressed the memory of a deceased person. In a recent article on ‘dark tourism’ for frieze, Ronald Jones asked ‘are works of art as powerful as the sites they attempt to memorialise?’.2 Lambe and Richardson’s exhibition — and, by extension, the entire gallery program that pivots around the simple curatorial criterion of ‘bring[ing] together artists and artworks around the circumstances of death’ — similarly questioned the efficacy of art (over object) to communicate the personal and collective impacts of death3

Certainly, utilising found objects for their associative or mnemonic qualities has been a conventional trope for artists working with installation since at least the 1970s (even Duchamp advocated a connotative interpretation of his readymades as early as 1917). Yet unlike most uses of the readymade in installation art, there was no pretence or suspension of reality underpinning The Memorial. Its curatorial methodology — like its ghostly display case — was laid bare. In this way, the presentation of objects in The Memorial appeared to be more closely related to the ancient ‘Roman Room’ memory technique (where a subject visualises a room in their house then mentally attaches whatever it is that they want to remember to the various ‘stable’ objects typically located within it) than it did with the contemporary art archive or the idiosyncratic modes of display often associated with private collections.

By placing the works in a syntactic hang, and accompanying the exhibition with a reflective publication that contained a short statement from each of the contributors about the object that they had chosen to exhibit, The Memorial actually partially turned its viewers’ attention away from the assorted personal items and onto the structures (both physical and immaterial) by which they were supported: memory, longing and, most strikingly, tradition.4 The network of narrative allusions that brought the objects together in such a poetic manner suggested that, as with phylacteries containing texts from the Torah that are worn on the body, the brunt of the weight of memory is carried equally by language as it is by symbolic object.

Helen Hughes is Assistant Curator at Utopian Slumps, Sub-Editor of un Magazine volume 4, and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.