Australia cannot pretend to be Europe, the differences are vast and deeply significant to us, and these differences are what we must realise so that we might develop a consciousness of our situation-identity.1

Having recently spent the month of July in Australia — mostly in Melbourne as part of Gertrude Contemporary’s Visiting Curators Program — this is a partial account of that experience now that I am back in London. It has been difficult to try and process the information and the wealth of encounters I had; this article wishes to present a textual and visual commentary on selected subjects discussed while in Australia.

At the Tate Modern, a major exhibition of Francis Alÿs has just closed: his subtle video performances manage to turn ordinary gestures into political actions, and his artworks retain a unique quality allowing us to see reality with different eyes. What a Belgian former architect seems to be able to achieve in Mexico City and in other foreign locations, is to see the (local) problems and possible solutions with more clarity — a prerogative granted by his status of ‘outsider’. I cannot prove that my vision and insight were sharpened in Australia, but I am sure of one thing: it was refreshing to have to come up with my own judgements on artistic practices, not having any clear point of reference, except for my Eurocentric art history. In Australia, I have never had the impression of being on the periphery. On the contrary, I have found a rooted curiosity and knowledge of what is happening elsewhere and, at the same time, an engagement with the specificities of a locality.

In London, I run the art space FormContent, and for me it has been extremely interesting to get to know the different typologies of art spaces in Melbourne and to meet the people that are involved with their functioning and conceptualisation. Similar to their European counterparts, most Artist-Run Initiatives evolve from the shared desire of peers to be involved in the process of exhibiting the output from the emerging scene to which they are affiliated. It would seem that spaces are typically secured in areas that were once not so appealing, and hence affordable, but become gradually fashionable and consequently unaffordable. In this respect, they too appear as short-term endeavours. As for differences, I find problematic the Australian custom for ARIs to charge rental fees for exhibitions as a means of financial sustainability. I wonder to what degree this affects the freedom of artistic gesture and limits the full extension of experimentation for an artist.

Books

I had never considered the way in which books become luxury goods when shipped to Australia when they are relatively accessible in Europe. In this regard, talking to Joshua Petherick and Warren Taylor was quite revealing.

World Food Books, managed by Petherick, sells international publications to a Melbourne audience. I went through the selection of titles trying to find common threads beyond a relation to specific publishers or distributors and as such considered the titles a good filter as to what might seem relevant to a group of contemporary art practitioners in Melbourne — as if every book on the shelves was really meant for offering theoretical references and practical inputs to specific Australian artists.

The Narrows, at the other end, acts as an agency that allows artists to test the boundaries of research through publications, editions and gallery projects. Warren Taylor and I conversed on the new timelessness of Times New Roman, and about the 1960s Brazilian cultural movement, Tropicália, a topic we are both passionate about. I found many points of contact between The Narrows and FormContent, alongside a rolling program of exhibitions and events, both organisations facilitate artists’ books and publications and offer a platform to test ideas that move beyond commercial endeavour, to support experimental, discursive and less object-based practices.

This bookish thread leads me to Stuart Ringholt, who I met in his studio / storage of pieces and ideas. I was introduced to the bound books he has been assembling from pages selected from copies of Artforum and other art anthologies. The books become sculpture when Ringholt cuts into them and, in doing so, he creates a new sensory experience from the visual material. Ringholt also handed me a thick book of compiled images that juxtaposed images of Barbie dolls with war zones and fashion shots on facing pages. The new narrative generated was both disturbing and powerful, and offered a different perspective on apparently unrelated topics.

On horses and expectations

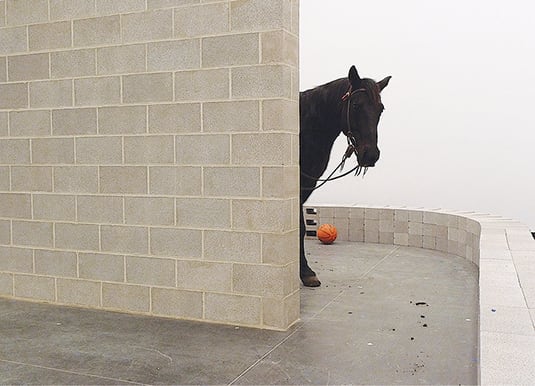

I visited Bianca Hester’s studio at the time when she was getting ready for her exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA).2 I had the chance to see the raw materials that became the physical points of departure for ‘situations’ that were to be enacted at ACCA. Since the exhibition opened, I have been hearing reports about a horse entering the space and activities between people with bikes, balls, ropes — all existing on the perimeter of the architectural discourse Hester elicits at ACCA.

Following horse associations, the first thing that comes to my mind is Jannis Kounellis’ 1969 intervention at L’Attico in Rome, where the artist positioned twelve living horses of different colours in the gallery. The art space was abruptly turned — albeit temporarily — into a horse stable where the horses, once considered symbols of freedom, became trapped in a confined space. Consequently many questions were raised about the status of the readymade, after Duchamp, but also about the connection between art and life and what becomes of the ordinary when recontextualised in a rarified art discourse.

The other association that comes to mind is Untitled (-Pureblood), an action co-produced by Patrizio Di Massimo and FormContent in 2008, in which a horse galloped from the borough of Hackney, North-East London, to a bank in the heart of the city’s financial district. The aim was to link the location of the inviting exhibition space to an equestrian statue positioned in front of the Bank of England. The project examined spatial distance and drew attention to the different economies of both locations while commenting on the dichotomy between reality and fiction and their possible representations. The action was carried out during rush hour, and managed to create a lively short-circuit with ‘contemporary’ London, introducing a different temporality and a suspension of disbelief in whoever would encounter the animal. The performance continues to exist in the myth produced by word-of-mouth distinguishing those that witnessed the action from those that just heard about it.

Looking Back. Looking At.

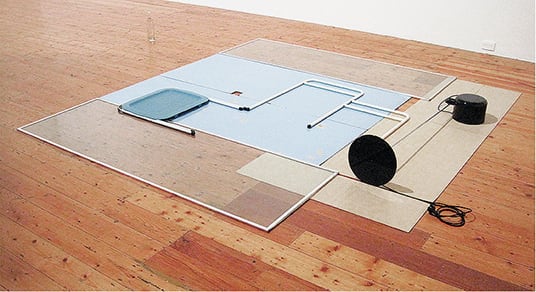

Lou Hubbard was installing at Gertrude Contemporary for the exhibition Still Vast Reserves II when I met her and had just arranged her installation Uneasy Body. Hubbard was trying to make sense of its placement on the floor and was open to discuss with me her installation doubts: making me part of her working method, looking, comparing and testing. I was interested to see how she considered her work spatially. At first as a singular entity and then adjusting all of its parts to ensure they were well-balanced and presented to the viewer with a certain formation from specific vantage points. She then fine-tuned her piece to the rest of the work in the group exhibition — looking for relationships with them rather than seeking isolation.

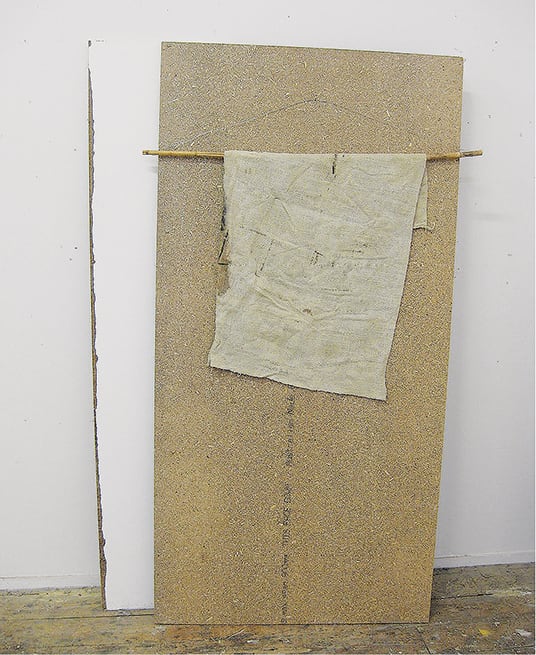

The visit to Elizabeth Newman’s studio and house effortlessly turned into a conversation that touched upon her life and artistic trajectory, her decision to quit making art and her choice to go back to it with renewed motivations later, after some years had lapsed. In her most recent body of work, I appreciated the instinctual approach that combines cold abstract-geometric shapes with warm textiles presented in various sizes. The sensual and visual strength of those bi-dimensional works can be transferred to spatial compositions that successfully juxtapose found objects with her wall pieces.

Nicki Wynnychuk’s artistic research investigates provisional states-of-being, through fragile formations obtained from found materials. Small images and arrangements on wider surfaces exist outside any specific definition of time or place. Coffee, bean bags, a blanket, flags, a table — all devoid of their function — were fragmentary examples of the shapes Wynnychuk’s thoughts take. The work is assembled and balanced quickly but it retains a degree of delicate precision. Generated from a constant reworking of the spatial connections and internal references within the constituent elements, the work resists any simple definition of sculpture. A meditation on the current state of things seeps through Wynnychuk’s constellations of objects; they embed a transformative quality that could make them rise from skeletal presences to bearers of a newly found potential.

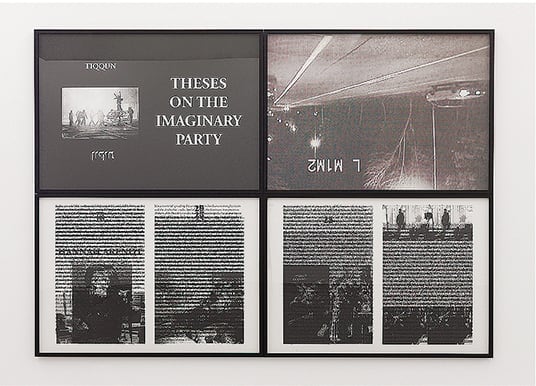

Can images have a truly revolutionary potential? What happens to agency when any attempt at change is reabsorbed into a capitalist circuit? Can aesthetics and politics coexist in a work of art? These are some of the questions Marco Fusinato tackles by means of art and music. I thought I had Fusinato figured out when I first looked at his website, but things changed when we met and began discussing what lies beyond the impeccable formalism of the work. We talked about art and politics through the figures of Joseph Beuys, Ulrike Meinhof and Cornelius Cardew, and about the possibility of sharing a political understanding regardless of locality.

I have recently seen two exhibitions in London of artists that were also included in the last Biennale of Sydney. One work I really enjoyed was Marcus Coates’ video installation, the other, which I had problems with, was a video by the Russian collective Chto Delat?, both at Artspace, Sydney. For his exhibition in London, Coates presented ephemera taken from his shamanistic performances along with the outfits he wore in his videos, which were displayed on mannequins together with their animals’ accessories. There were handwritten posters with excerpts from speeches he delivered in his performances and a vitrine with a display of improbable objects: a necklace made up of £20 banknotes, feathers trapped in onion nets, glasses, and books about birds. It felt as if all of those things remained very much at an inanimate level as objects, the residue of energy expended elsewhere.

Chto Delat? currently have a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.3 Here, the exhibition space is filled with monitors and projections; there is writing on the walls and published collections of essays on communist contemporary strategies. I have grown disenchanted with activism presented as such in an art environment, I believe a solution closer to Fusinato’s way of trying to match a sincere political concern with a refined artistic presentation could be more effective than shouting slogans.

Caterina Riva is an Italian curator working in London, where she is the director and one of the founders of FormContent, a curatorial space existing since 2007.