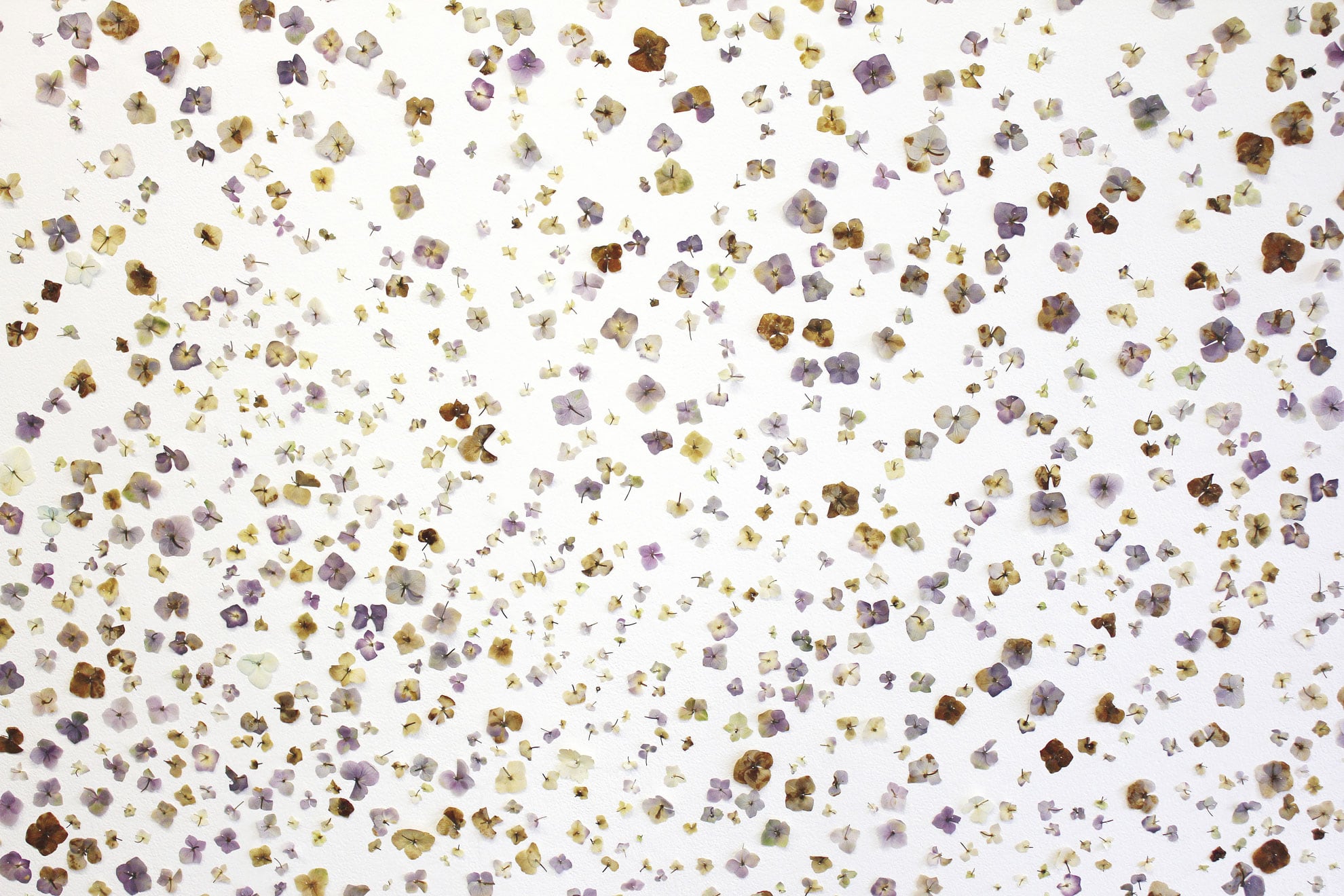

Recently, I was on the phone describing Heidi Holmes’s installation at West Space in September 2016. ‘It’s this incredibly great work’, I said. ‘Normally there are big windows along one half of West Space gallery, but Heidi has built a room that covers these windows, with only a small square of light peeking out — the shift from the open gallery to the shrunken dimensions of a domestic room is stifling. Near the window is a skin-coloured candle that stands at the height of Holmes’ vagina, which will burn throughout the exhibition. And on the walls are fragments of pressed flowers — from Heidi’s previous exhibition — which have been crushed to look more like specks of bark and dirt. Also, if you press your ear close enough to the wall that covers the window, you can hear a pulse mimicking a heartbeat — scratchy and repetitive. It’s called (I’m Pretty Sure) there will be no science baby with the ‘I’m pretty sure’ in brackets because Heidi’s not really sure there will be no baby. It’s like a limbo possibility; neither the possibility nor the impossibility can be imagined. Oh! I forgot to mention it’s about Heidi’s IVF treatment, which hasn’t been successful and won’t continue anymore. So now she’s…’

My sentence drifted off and I began to feel ridiculous and invasive as I realised what I was talking about and who I was talking to. The person on the other end of the line was someone who had had multiple miscarriages, one ‘miracle baby’ and then one final miscarriage of twins, before being told she would never have another child again; we both knew it and we both didn’t talk about it. And yet here was Heidi Holmes, talking about it.

Holmes’s exhibition at West Space (I’m Pretty Sure) there will be no science baby is the third in a series of works revolving around Holmes’s attempts at In Vitro Fertilisation treatment (IVF) with the first installation I am woman hear me roar as I push out this science baby at BUS Projects in May 2015 and the second Control Yourself (even if you feel dead inside, hurt and barren) at Kings Artist-Run in May 2016. Holmes’s inability to naturally conceive stems from endometriosis, and between mid-2014 to mid-2016 she attempted IVF treatment nine times, before deciding in August 2016, a month before the last installation, that there would be no more attempts. The installations, collectively referred to as ‘Science Baby’ works, were conceived in tandem with the prognosis of Holmes’s IVF treatment.

While we often make implicit distinctions between the person, the work and the practice (art is not a person — a person is not their art), Holmes’s practice and work confuses these neat categories by not simply being autobiographical or highly intentional, but utterly personal. The miracle isn’t that Holmes addresses her female body through an aesthetic lens; the real miracle is that she articulates things about her body and experience without regressing into trite sentimentality, didacticism or mundane rehashes of ‘the body’. Holmes’s personal gestures further tie her body, feelings and experiences with wider contemporary contentions: capitalism, feminism, nature and technology, with the intuition that an underlying logic ultimately connects these facets.

A Catalogue of Feelings

Can you tell me how the three installations came to fruition and what made you decide to use your experience of IVF as a basis for your work?

I’ve always had this autobiographical practice and I really, to be honest, did not want to make these works. I thought it would be very frightening and confronting. I didn’t want to be the poster child for the woman making work about IVF and therefore talking about feminism and other scary subjects to talk about in art, or perhaps frowned upon in some circles. I actually didn’t feel qualified to talk about those areas. I really tried to avoid it, but ultimately the choice was to either make work about this subject, which was happening in my life, or to make nothing at all, because I could think of nothing else.

What do you feel are the consequences — limitations and freedoms — of using an art practice to investigate what are often deemed as ‘personal’ and ‘female’ matters of the body?

It can be isolating. I feel I’m sometimes corralled into the ‘feminist artist’ category — though I think my practice examines ‘being human’ more than anything else. Due to its personal nature, my practice and the IVF are both difficult to talk about. It’s really real for me — quite literally in real-time. I was actively undertaking IVF treatment as I was exhibiting these three ‘Science Baby’ shows. If I’m making work about grief, I’ll still be grieving. By exhibiting the work I acknowledge that I’m inviting conversation [and] dialogue, but I need to protect myself a little from these conversations, as the feelings are very raw. And so, for my mental health and for my partner’s benefit, there is some trepidation in speaking about the work.

TM: Was the overall trajectory of the works conceived from the outset? Did you think there would be multiple works relating to IVF?

No, the works were developed over time, without any foresight. The first show (at Bus Projects, May 2015) was formed on the terror of what was happening to my body when I was taking hormones; what was next, having people prod and talk about me and look at me — all in medical terminology. It was about the fear of what was going to happen and the unknown of what would be next. The first show was near the start of the IVF process and the second show was eighteen months into the IVF process, so I’d had eight failed attempts by then and I’d had copious amounts of advice from friends and family. At this time I was balancing trying to be hopeful, but at the same time trying to be realistic: talking to my doctor who was saying it’s a really slim chance you’re going to be successful. So the second show [at Kings Artist-Run, May 2016] was more about balancing the hope and the grief. Then the third show [at West Space, September 2016] happened really quickly after that, about three or four months after. And because I had spent so long working on that second show, by the third show I didn’t actually know what I was going to do. But it worked out that between that second and third show, my doctor advised that she would be willing to see me though one more attempt and if that was unsuccessful, that I should not continue with treatment. However, Tim and I decided that we were not able to continue with the treatment, regardless, for both emotional and physical reasons. And so the third show became about grief. But I could never predict from that first show whether I’d be making my third show about grief, because I hoped I would have made it about being a mother.

Do you find the process cathartic?

I’m not sure. I find it helpful to my life in general to make art and be an artist because I think that’s what I’m to do. So not doing that would be very bad for me. So generally speaking yes, art helps with everything. But I wouldn’t exactly describe making these works as cathartic, though I think there is some benefit in processing these feelings. Rather, to me art is intrinsic. It is as much to me, as me drinking a glass of water is to my body; essential and unavoidable.

In my experience many works that broach female-related body issues — whether these works are a political or cultural investigation of the body or displaying an experience of motherhood — can often be didactic, trite or become so abstract as to be nonsensical. Yet I find that you’re talking about your body in very specific ways that avoids these pitfalls. How do you manage to create art about your body and personal experience in this way, and do you think your work can be read without thinking of your specific body?

I think in the long lead up times I did make those cliché, bodily works. And I guess through the process I make them — I have to make them — and then I throw them away and then move onto the next thing until it builds into something that represents all of these things, including the body. It’s a developed practice that accumulates references and materials over time. And so it’s abstracted in that process. But my body is still very present in the work, in all of the shows actually. In the first show with the ultrasound machine, the hormone material that I put into the water had also gone into my body, so that’s a link. The probe that was on the wall was used — but not by me — and was hung at exactly the height of my mouth. So it’s there, but it’s subtle if you don’t know. I think you can still get something from the show if you don’t know about those things though. If you just see the surface of the walls, or listen to the sound, so I don’t think you need to read my body in the work, in order to read the work.

Art is eBay and Ten Litres of Ultrasound Gel

While there are always concepts and ideas, you can often boil craft down to a series of pragmatics. For Holmes these would be a Northcote-based studio, a vaginal probe on the wall, writings from her partner Tim, a baby doll stuck up high, pressed flowers that total in their hundreds, ten litres of ultrasound gel, writings, secret hospital photos, hormones leftover from treatments… Holmes’s process is one of collecting endless data and materials to alter and re-contextualise them. Simply sitting among the collected materials, I imagine, gives Holmes certain sensibilities and perspectives when creating. Probes, flowers, hormonal liquid and ultrasound gel have stopped signifying what they are supposed to, and now Holmes’s materials must work to signify something new — bittersweet and sad.

On her studio wall, Holmes also has lists of abbreviated script written on white A3 office paper with a large black sharpie. Crappy ideas are always written on these lists; crappy ideas are crossed off. Lists will always get written away from the studio (there is no true ‘away’ time), but are only official once stuck to the wall. There is a list for every material in Holmes’s installations, but some of these items do not make the cut, for there is also a set of criteria: Holmes’s marketing background is the thinking point that determines strategic intentions and communication techniques. For Holmes there is a simultaneous desire for accessibility and intrigue; for a work to reveal its thoughts, but to also hold its ideas close to its chest.

Making art often leads to strange places. It often leads to eBay and Holmes tells me the story behind the centrepiece of her first ‘Science Baby’ installation, an ultrasound machine, which was purchased on eBay for $200 from a woman in Melbourne and later squeezed into the hatch of her car. Holmes tells me:

It’s a pretty strange thing to have in suburban Mornington, in her garage. But she [the seller] said as I was leaving, ‘I’m fascinated, what are you using this for?’ And I said, ‘I’m an artist, I’m going to make a sculpture or water feature out of it.’ She was like, ‘What’s the work about?’, and I say, ‘It’s about IVF. I’m doing IVF at the moment.’ And she said, ‘Oh my god, Heidi, that’s why I have this machine!’ She had failed at IVF. She’d had fifteen tries and it hadn’t worked, so she decided to dedicate her life to collecting decommissioned medical equipment and shipping it off to a hospital in Africa that would use this equipment on their patients. This particular machine was too far gone, she couldn’t send it.

And Somehow Pragmatics Are Also Concepts and Installations

When collecting and collating material for an installation, how do you decide what finds its way into an exhibition? Is it an intuitive or calculated process?

The development of a concept for an exhibition is absolutely an intuitive process. It begins with a ‘thing’. Something real; an event, a feeling, some kind of experience, some ‘thing’ that I can absolutely not shake. It’s usually something yucky and so it’s hard to deal with. It will be the last thing I want to analyse, pull apart — but as I said, it cannot be shaken. And so this ‘thing’ is pulled apart. Written down. Listed. Talked about in therapy. It is broken and busted up and fragmented. The broken, busted up, fragmented ‘thing’ is then processed into materials or outcomes. This is when the exhibition-making becomes more lateral [and] strategic. I collect a lot of materials and ideas for outcomes. Make extensive lists. I mark out areas in my studio — a floor plan or a wall size — and arrange and test and add and subtract and think and think and think.

From searching around the theory and literature on women, bodies and birth, most work seems to discus the ethics and agency of a woman’s body and the phenomenological experiences of motherhood. Yet accounts of a body in a state desiring pregnancy, but not being able to be pregnant, is almost non-existent. Your work clearly gives ontological validity to the desire to become pregnant and be a mother, but I also sense that much of your work points to a loss of agency over this desire. Is your practice, thought-process and installations a way of perhaps reclaiming something that is lost?

This is hard to say, but I feel that I’m a bit twisted about it at the moment. I feel shameful, but I hate my body. It’s really disappointed me. To menstruate every month is torture; to know I have a reproductive system that’s not productive is devastating; to still suffer through endometriosis every month is so disappointing. But that is a really embarrassing and disappointing point of view. If another woman was saying this to me, I’d think it was awful. But that’s where I am. I think I’m just grieving through my body. I guess making the work is helpful with that, but it’s also embarrassing. The rotten flower scent represents that hate. But I find it [this type of thinking] so offensive, it’s so detrimental to our cause. But I’m there and I’m looking for the way out.