A body lies hiding beneath a thick sheet of black plastic, the kind used by firemen to extinguish fire. Giving way to movement and form, the plastic becomes a percussive skin used to thrash out sound. A release of manic energy. Finding quiet in the rage. ‘I used that a lot to go into that inner space where you don’t want to get exposed, sometimes you put out so much that you have to recover; under the black plastic you get release and calmness’, says Sydney artist Wart of In Between Breaths, presented as part of the Performance Space program Accidents and Alchemies in 2006.1 Finding poetry in unlikely materials, this ‘cover up’ for Wart is a requiem for ‘recovery’ — a double-edged sword where you could suffocate and choke while catching breath beneath an oppressive blanket of night.

In Between Breaths represents an important retrospective juncture in Wart’s almost four-decade long career. Through that work, she takes stock of what it means to have lived with a mental illness since diagnosis more than a decade earlier: ‘In the early days being inspected, selected, detected and neglected… Left to wander the wards in a doped-up haze of drugs, meandering aimlessly for months’. Wart talks as much as she paints or performs, a musical knack for language, mining the ‘deep and meaningless’ with a playful sensibility that tips often into abjection and excess, having lived as she has on the fringe and at the centre of it all: ‘I have a bit of a reputation, I forget what it is though.’2

Wart’s story is punctuated with highs and lows, peaks and plateaus, hospitals and studios. Growing up on the outskirts of Geelong in Victoria with a menagerie of animals as pets, ‘Jen Waterhouse’ was the third of five children born to surgeon Dr Bob and Barb Waterhouse (née Dahlenburg) in 1958. Bob and Barbara’s offspring were affectionately nicknamed ‘Warts’ but for the middle child it stuck: an apt epithet considering ‘Wart’ encapsulates the artist’s appetite for art and the comic grotesque as much as it is a political declaration of cancerous anti-sociality. Her mother Barb died from leukaemia when Wart was fourteen, leaving her working father the challenging task of raising the family. Bob later remarried Jean, a local theatre nurse and hospital administrator, with whom he enjoyed a long and happy life.

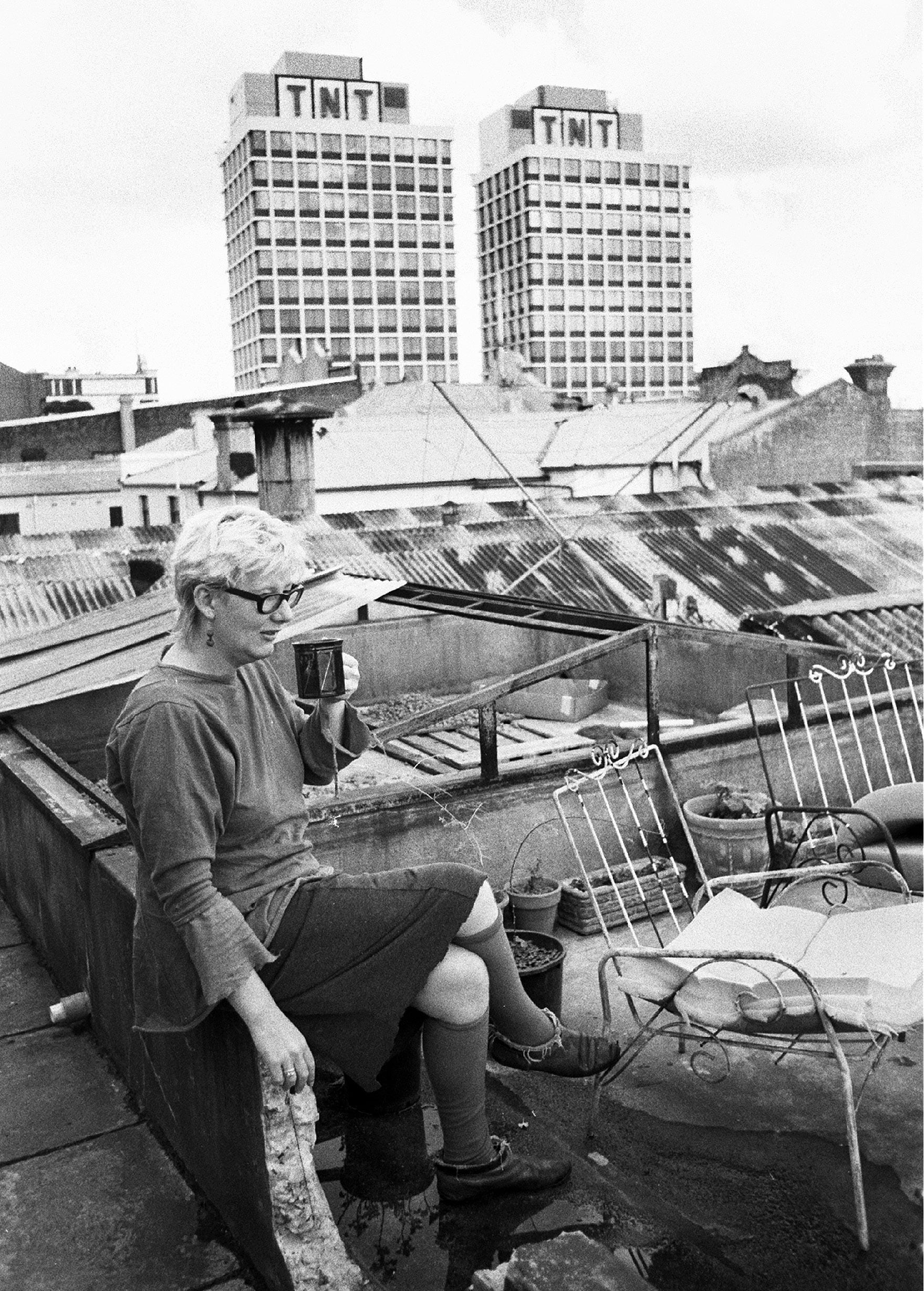

Wart studied art and design at Deakin University in the mid-to-late 1970s. She attributes her ‘graphic eye’ to these formative days training at Deakin’s ‘Old Mill’, submitting tough design projects on rape while supplementing her income as a life model. As soon as art school was completed in 1979, Wart headed straight to pre-gentrified post-punk Sydney to make her name as an artist. From 1981, Wart and her infamous dog, Kero (a Blue Heeler named after kerosene: ‘fast and blue’), held a string of live-in studio residencies among a legendary scene that is regarded as having birthed some of the earliest artist-run initiatives in Sydney: etc. Studios, Art Unit and Slaughterhouse, which later morphed into Sylvester Studios before ending in 1995 as Selenium.

Spearheaded by artists Robert McDonald and Juilee Pryor, Art Unit on Henderson Road in Alexandria was particularly important in shaping Wart’s early life as an artist. Academic Ann Finegan remembers Art Unit well:

Harnessing radical energies, unlikely materials, processes and anti-bourgeois aesthetics with post-punk grunge sensibility, Art Unit was no Australian wing of modernist, minimalist conceptualism. Rather it had an affinity with the Situationist ethos of détournement, found object and Gutai performance. Art Unit had a radical, even destructive edge, closer to the cultures of the street, to excess, to the socio-politics of Bataille and Artaud.3

Presented under the moniker Food Sluts Unite, Wart staged a show at Art Unit in 1983 called Total Fat where food was left to rot in the gallery to enhance the experience. Wart’s show was on one side of the gallery while Simon Penny’s Further Adjustments was on the other. Pryor recalls: ‘Art Unit was a big thing for Wart and she was a big spirit and big heart in the centre of all the swirling chaos and action.’4 Wart rattles off a few examples of her role in the bedlam:

I often put myself up as the lucky door prize at Art Unit events. One time I learnt how to fire breathe from a stunt man; another time I was left to run the place for three weeks and I put a big red W next to the sign out the front and it became WART Unit!

When she wasn’t misbehaving at Art Unit, she would loiter at Performance Space in Redfern. ‘Art Unit and Performance Space’, writes Ann Finegan, ‘were ideological complements, with artists circulating across both’.5

Throughout the 1980s, Wart’s practice fused commercial design work with an emerging painting and performance practice. Her most recognisable illustrations and graphics included a recurring cartoon strip in a Sydney’s City Hub newspaper on her dog Kero’s adventures, along with album covers, posters and t-shirts for Mental as Anything, The Cockroaches and Midnight Oil. Co-designed with photographer Ken Duncan, Midnight Oil’s iconic album cover for Diesel and Dust (1987) won an ARIA Award for Cover Art in 1988 — despite Midnight Oil’s then manager Gary Morris having remarked: ‘“I don’t know why Midnight Oil chose you Wart, you don’t look like a proper woman”— just because I had a mohawk!’

Produced under her freelance business name Warts ‘n’ All, her designs, cartoons and hand lettering were characterised by witty and biting social commentary to convey the urgency of social issues like sexual health, abortion awareness and gender politics. This was a decade where her social consciousness was being shaped by community work with underprivileged youth on the one hand and through her role as designer of safe sex campaigns during the early days of the AIDS crisis, on the other:

I devised a series of cartoons to get humour into condoms. The series was about Siamese twins Mohawk and Westie — they ‘get it on to get it off’. Tony Duke and I became ‘Ma and Pa Condom’ — we did radio and some telly: Beatbox on the ABC, we worked with ACON, the Australian Prostitute Collective. We got into it through grief, it was such a devastating time, the HIV ward was so sad.

As the 1980s came to a grinding halt, Wart’s focus became fixed on mental health advocacy and support, especially after she was finally diagnosed as schizoaffective — an illness often difficult to diagnose because its symptoms resemble both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. ‘I get like an antenna head’, is how Wart describes her symptoms.6 Wart’s first ‘episode’ happened in 1988 — ‘the year of hate’, as Wart calls it. Taken to a psych ward at Gladesville Hospital by a police escort in an ambulance, Wart remembers the place as ‘really scary and really old’. Her first psychiatrist was Dr Dennis Pisk. ‘I kept on calling him Dr Pissed!’ From 1995 Wart was admitted into the institution formerly known as Callan Park Hospital for the Insane. Renamed Rozelle Hospital a year before Wart (and Kero) moved in, this site would become defining in life and career terms as it coalesced her self-care with an increasing profile as an arts worker and activist in the mental health sector.

Helped along by the hospital’s relationship with the Sydney College of the Arts — SCA was founded on the site of its first decommissioned psychiatric hospital — Wart’s work became increasingly focused on her experience of institutionalisation. ‘Hospital borders are significant structures for Wart, who recounts the lines of demarcation (and their associated privileges) of various psychiatric institutions’, notes Anne Loxley.7 Fast and loose with brushstrokes bleeding bold colours and mark-making that oversteps comfortable boundaries, Wart’s paintings are a diary of what hospital life looked like for her. Visceral in approach, paintings such as Hospital Dreaming (c. 1995), Isolation Room (c. 1995) and Don’t Go Beyond the Steps (c. 1994) present the brute truth of the artist-as-patient’s subjectivity, beneath which lies the warm charm she exudes in person. Signed lower right is a variation of her name — Warts ok — a pragmatic glimmer of optimism amid dark times.

A decade after her first bout of hospitalisation at Rozelle Hospital, more than thirty of Wart’s paintings were curated into the landmark, multi-venue exhibition *For Matthew and Others: Journeys with Schizophrenia (2006) across Campbelltown Arts Centre and Ivan Dougherty Gallery at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). On display at UNSW were her important series of twenty-four self-portraits, Secret Phases of Fear* (2005), which depict an escalating manifestation of mania during paranoiac states. ‘Moving from raw figuration to smeared abstraction, the series is a slow revelation of naked agony’, continues co-curator Anne Loxley.8

At the UNSW opening event Wart performed My Choice to Breed (2006), where she simulated childbirth. A nod to Leigh Bowery’s 1994 Wigstock performance that saw him have an adult baby on stage while singing Love Stands Tall and Free, Wart made an entrance with a massive ‘baby gut’ that expelled an ‘ugly’ baby sculpture made of foam. While mental health advocacy was a strong thread in her works in For Matthew and Others, this performance demonstrated Wart’s strong pro-choice activism during this period.

Wart describes the experience of ‘outing’ her mental illness in the art world as ‘sort of good and bad … it was a good exposure thing, but I don’t want people to see me as an Outsider artist’. Wart’s work, particularly as a painter working in an expressionistic style, belongs to a lineage of contemporary Australian art — from Joy Hester through to Davida Allen, Jenny Watson and Tomi Ungerer. The psychotic energy of her paintings with their lurid impasto palette distorts the body to breaking point as an externalised manifestation of a busy mind working overtime. Furthermore, Wart is quick to assert that unlike her own trajectory, Outsider artists are generally untrained and removed from the art world, working in relative isolation from the support that comes embedded in a community of likeminded artists.

For instance, in 2009, Wart used her formal training as an artist to establish The ARC, an art school based in a building at Rozelle Hospital called Daintree Lodge. For three years, this workshop-style facility was ‘for loopies run by loopies’, as she puts it. Some years earlier Wart appeared as one of twelve female mental patients performing in Javier Téllez’s two-channel 16mm film installation La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Rozelle Hospital). Among Wart’s frank observations to Téllez about her experience of mental illness, she says:

It was funny, I was in the pub the other day and this guy came up to me and he said, ‘I want you to fund some money for the Paralympics’. And I turned to him and said, ‘Look buddy, I have the Mental Olympics every day!’9

Commissioned for the Biennale of Sydney 2004 — and now held in international collections including La Caixa Collection of Contemporary Art and The Museum of Fine Art in Houston — Téllez’s work inspired The ARC that would go on to become the short-lived art school at the hospital.

While at Rozelle Hospital and during a residency at the Bundanon Trust in 2004, Wart devised a performance called Sex Mental (a work that later morphed into In Between Breaths). Using found objects as symbolic props, Sex Mental was a hybrid of absurdist theatre meets sex education lecture. Drawing on the conventions of feminist performance and queer nightclub spectacle, the remarkable thing about Sex Mental was that it was not initially performed in gallery settings but on the medical conference circuit. Most notably, Sex Mental made its way to Venice in 2007:

I wrote a paper on it and submitted it to IPSI [Information Processing Society, International]. It got accepted and I performed it in front of these professors in science and maths in Venice. I stayed in Venice for two months where I talked my way into playing piano in a bar for food and wine. I took photos on throwaway cameras of my performance bra in all sorts of places through Venice.

Wart has not had a studio since the closure of The ARC in 2012. Due to the lack of space, most of her work these days consists of small paintings commissioned by friends, or in the form of live performances including memorable appearances in Bec Dean’s Performance Space programming: Benevolent Asylum: Just for Fun (with Lily Hibberd) in 2011, Sexes in 2012 and You’re History in 2013. A throwback to her farm upbringing, pets have been Wart’s most consistent cohorts: sadly, Kero died in 2003 at the age of eighteen after which Wart staged a solo studio show in her honour. For some time, Wart had a Rainbow Lorikeet called Fingers who flew away to be with a girlfriend that Wart christened Fingered. Wart’s current long-time companion is Captain Moonlight, a tawny toothless cat that plays the upright piano lining a wall of her tiny kitchen. When Moonlight is not walking up and down the keys for attention, Wart uses it — along with her guitars and harmonicas — as practice for occasional pub gigs for her one-woman band, Dad Wears a Ponytail.

Nearing sixty, Wart has spent much of the last two years, since her father died in 2014, hiding out to find solace for growth and future renewal. Retreating and resurfacing is part of her process for life as much for art, as is making noise within the deafening silence afforded by black plastic, fighting for breath.

A companion piece to this article is available online as part of un Extended 11.1.