I can never have a poker face.

Anybody looking at me can tell exactly what I’m thinking.

— Gena Rowlands

In May 2016, I invited 100 men to participate in a short scene derived from a John Cassavetes film, Opening Night, as part of a 24-hour durational performance at Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) for the Next Wave Festival. The scene focused on two characters attempting to maintain connection despite the demise of their romantic and erotic attraction.

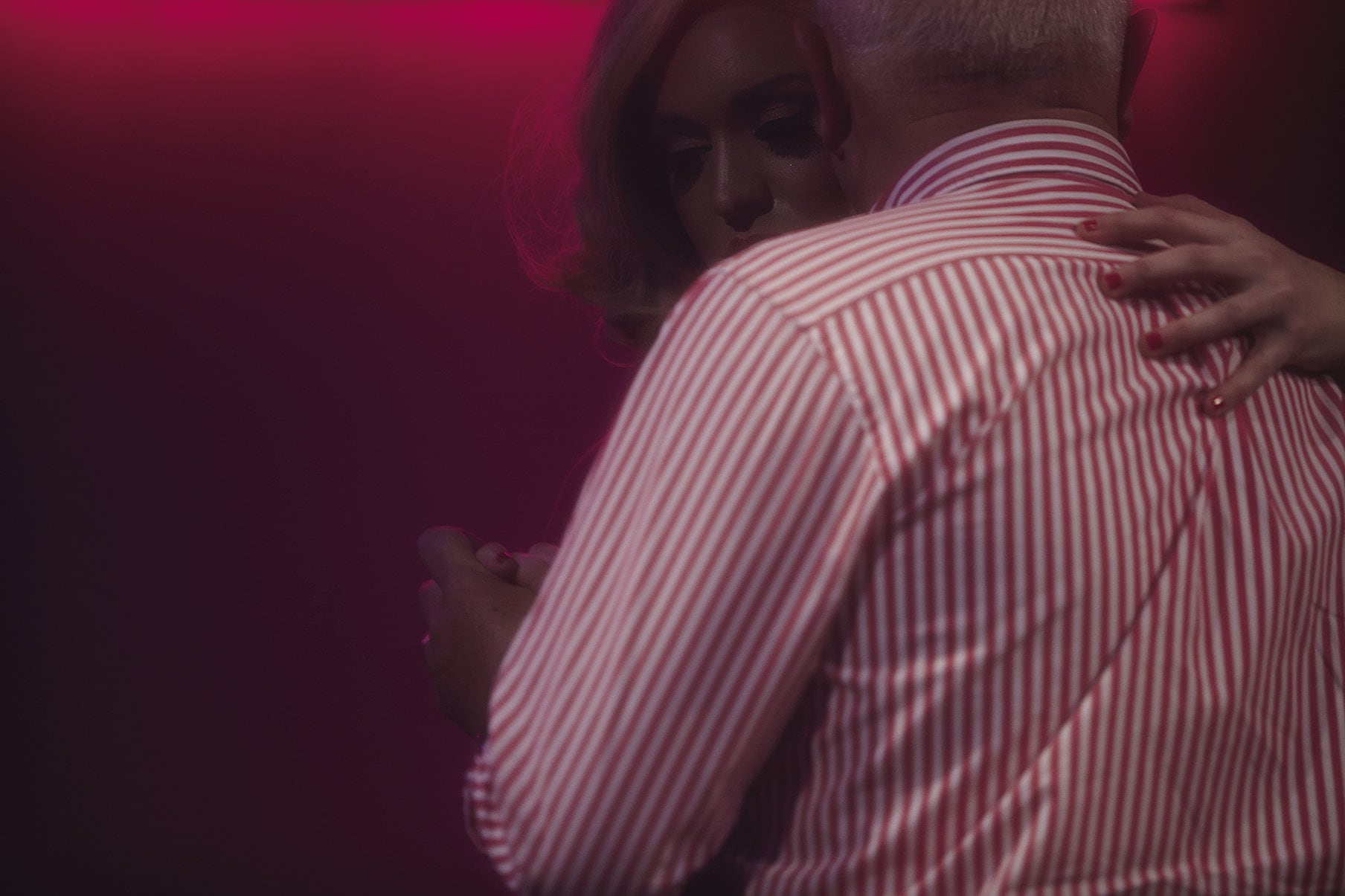

The performance took place in a fuschia pink room constructed within Studio One at ACMI. Central to the work was a live video component capturing each encounter in a cinematic close-up. The action was filmed by two camera operators on handheld rigs, live mixed and projected onto a screen, adjacent to the performance. I performed the role of Gena Rowlands’s character and male-identifying participants from Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra played the part of John Cassavetes, her lover both on and off-screen. The deal was simple: for a small fee, they had to learn a short piece of script and perform it in front of a live audience.

Each run of the scene lasted approximately five minutes. A man would come into the room with takeaway noodles, perform the scene, get paid, then leave. This happened on rotation from 1 pm Friday to 1 pm Saturday. I remained in the space for 24 hours. Those that participated ranged from strangers, to acquaintances, to friends, to family members. Some were trained — many were not. Some were drunk, some shy, some high on narcotics and some completely off script and rogue. Eighty per cent of the participants were strangers; every time they entered I never knew who would be next and what kind of energy they would bring. There was some room for improvisation around the text and physical freedom (as well as a healthy dose of physical contact). There were moments where I felt genuinely connected to the participant. Over the 24 hours I felt a range of: excitement, boredom, frustration, anger, arousal, sadness, amusement, fear, and sometimes cared for.

My dad, Allan Randall, surprised me as the final participant.

I asked Dad to recount his experience of his five minutes performing in The Second Woman:

I think you were at the front of the stage, looking out the front of the set as I walked in. When I first saw you, you looked vulnerable and tired. I’m sure there were tears in your eyes when I handed you the flowers. As your dad I felt quite concerned for you. I was determined to follow the script and I’m pretty sure I was to whisper my name into your ear so you’d know who was on set with you.

I whispered:

‘Hi Nat, it’s Dad’. Even though you obviously knew it was me! (d’oh!).When they led me from the green room I was so nervous. I concentrated on just putting one foot in front of the other and holding onto the food and flowers for you. I had only decided to take part on the way to Federation Square, where Nikki gave me the script to learn. This was the first time I’d seen it, so I started reading it over and over again to try to remember my lines and how and when to react to you on stage. My overwhelming thought was ‘I’m not an actor. I must remember my lines!’.

My main worry was stuffing up. My neurologist noted that in addition to a shaky left hand, I have facial masking which impacts my expression. I’d noticed this for a while, and people also told me it was sometimes hard to hear what I was saying. I recall making an extra effort to project my voice on set, although I’m not sure if it worked. I was concerned about how I was coming across and how you were reading my expressions.

My parkies [Parkinson’s] is eroding my self-confidence, insofar as it involves impeded memory, facial masking and likely becoming what they call ‘disinhibited’, (emotional, and possibly inappropriate behaviour) not uncommon for the disease.It’s been a long time since your show, so my memory of the text is very hazy. I know you were distraught, perhaps drunk (actually drunk?) and emotional. You threw the food at me when I set it on the table. It was a bagel because you had run out of the noodles.

I’m not sure what was said, but I know you were upset and started to dance with me. You guided me slowly around the floor. I had no idea what to do after. Under the music, so no one could hear, you whispered ‘how are you going?’ I replied that I wasn’t sure what to do. Whilst we were shuffling around, you told me not to worry and you’d lead me through the rest of the scene (phew!). Then you told me to get out. But before that you offered me money. As your father, the decision to take it was not an option.

I had no previous knowledge of this movie scene, so by now this whole stage interaction between you and me seemed odd/incongruous. I was still affected by your fragile appearance and thankful that your performance would soon be over. Before I exited, I had the option of saying ‘I never loved you’ or ‘I’ll always love you’. As your father it was a no-brainer for me.

Bravo Natski

Dad

I’m not sure if it was the sleep deprivation, the ‘real’ whisky backstage, or that I hadn’t seen Dad in some time, but when he walked on set it totally broke me. I’m not one for sentimentality but Dad participating in my work was really special. I felt a genuine authentic connection performing alongside him, despite the excessive artifice, the audience peering into the room and the inappropriate lover dynamic we were playing out together. LOL. I felt like we moved through the scene together, genuinely caring for each other, concerned about every step and every line that we spoke.

I remember backstage after it had all finished, I said to Dad, ‘I was so worried about you not being able to make it through’, to which he replied, ‘I was so worried about you not being able to make it through either!’.

Thank you, Dad, for humouring me — twice.