Like so many insidious and powerful organisations before them, Bababa International (BI) prefer to remain undefined. At present, its six members are nameless and the collective will only agree publicly on their location (Bababa International Airport, Redfern) and their commitment to making and exhibiting art under the BI designation.

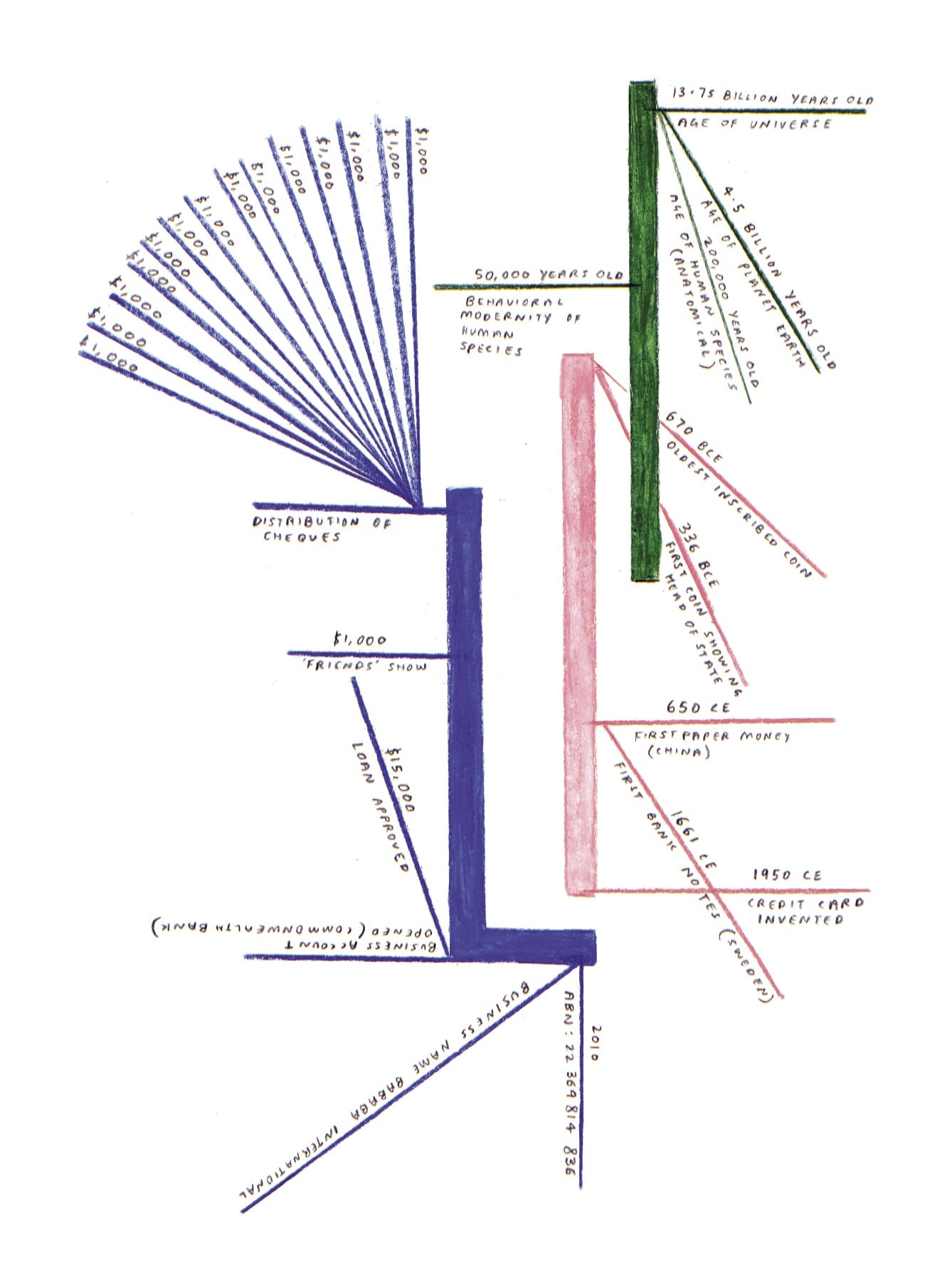

Perhaps it is this indifference to norms and platitudes that led them, as part of Investing, to obtain a bank loan of $15,000. This was distributed among 15 artist friends as their contribution to the aptly titled Friends show at Melbourne’s TCB Art Inc. in September 2010.

Previous works, including a rooftop mudbath (Imbroglio City (Unit 1) for Melbourne’s Next Wave Festival in 2010) and a soap-making apparatus offering sudsy maps to a nearby shower (Soap City at Firstdraft, Sydney, 2009), were self-contained; both mechanically and in the sense that their course of action was finite. In contrast, Investing has arguably been dwarfed by its yield: an enormous and steadfast financial debt.

BI now find themselves in an opportune moment to reflect on whether it is truly possible to circumvent the banalities of money and time. Amelia Stein met with the group to consider their strategy.

Can you explain what occurred in the Friends show?

The original thought was to somehow fund the show, so we decided an efficient way of getting the money would be to take out a bank loan. $1,000 seemed like a good amount, as it was large enough to be useful but small enough to remain manageable, so we took out a $15,000 bank loan with the Commonwealth Bank and sent a cheque and accompanying letter to each artist participating in the exhibition. We called the work Investing. Its more burdensome sister work is called Debt.

The action was a little naïve on our part. We speculated that the money would manifest itself in the show or immediately after, through some kind of collective or individual action — whether that be one spectacular act of communal spending or a sudden response to the money itself. I think a quicker response, generally, was predicted. But the response has been quiet, staggered and, in some cases, mysterious.

Has much been made with the money?

One artist is repaying us by drawing a one-cent coin ten times a day until the equivalent of $1000 is reached. He expects to pay off the money in approximately 27 years. Another artist is building a bike as part of a larger project in which she charts the solar system from within the boundaries of a city. We know someone else who is travelling to Indonesia to make work and another who went to New Zealand and used some of the money to make pasta for us. One artist had to spend the cash on bail after finding himself in prison…

Another artist has made it clear to us that he will never cash the cheque, however, we might take this opportunity to make it clear to him that this money will always be available to him.

Other than that, not many other details are known. We intend to eventually find out, although it would also be ok if nothing was made, if the money just filtered back into daily life and was used to pay some bills or buy groceries.

And what about Debt? Do you think of that as something that has been ‘made’?

The initial, stupid, flippant act of sending the cheques felt like a work but now, given the reality of trying to get out of debt, it feels unresolved and kind of confusing.

Calling the debt an artwork is redundant, because it’s not creative or imaginative. When you’re making an artwork you’re quite free to do whatever you want; give or take practical considerations.

How do you plan to repay the debt?

We have a maxim at hand when dealing with the debt: Do Everything. We have founded a website design company called Internet, attempted to wriggle into the world of food professionals with Bababa International Conceptual Catering Service, started a high-end alcohol and service company called Santé, jumped on menial tasks such as handing out flyers, looked into low-level gambling, scratched scratchies, thought about offering handyman services, started a professional photography service for corporates and currently have plans to open up an illicit taco kitchen. Any other suggestions are welcome.

What appealed to you about obtaining and distributing the money as a work?

I like the idea of the work being a collection of facts — and entering these facts into a situation, or the show, or the world. It’s a game of belief: we believe in the artists and the artists have to believe that the money is actually there. There’s that and then there are the mundane facts of the debt. But the reality of the situation is indisputable, no matter what you think of the work.

The other thing we should stress is that it shows a lot of faith in the other artists and in art in general. We could have given $15,000 to anyone but we started there. They can take this money that is, to a certain extent, neutral and has nothing pre-programmed into it as a medium, and do something interesting, challenging, beautiful, unexpected … they could transform it through the freedom of whatever it is that makes them an artist. In a way, it’s contributing to a climate where creativity is legible and available to anyone and everyone. Hopefully, the people we gave the money to will make that creativity legible and turn the money into something, whether it’s a series of drawings, or a bike, or a new pair of shoes, or some chocolate biscuits. These are real outcomes.

It’s more open ended in that way than any of our other works, because there is no narrative that we can predict. The work has happened and continues to happen — it occupies both sides of the coin.

We were excited because the actions people could take were completely undetermined.

How do you maintain ambition and optimism about the response each work will attract?

With a lot of confidence in human nature.

Having said that, your work often seeks to subvert or even reject norms. Can you explain this to me?

That’s tricky. Rejecting the usual way of doing things seems to be a bit of a mainstay in the history of art so, in many ways, I’d say that any rejection has become somewhat of a convention. Perhaps with Investing we wanted to do something that relied on conventional practices but utilised them in a different way. Money is a familiar, irritating, stressful, serious material. We wondered if we could override these connotations by unlocking it from them.

Our mindset is that every-thing that does not exist in nature — everything that is human — has to be invented and this goes for art as well. Just like you would represent a vase in three-point perspective or explode it like a cubist, everything in art is arbitrary in the sense that it was invented by humans for other humans — from grant proposals (although you have to toe the line a bit more there), to your artist bio, to what you call your studio, to how you propose to galleries, to the work itself. Perhaps arbitrary isn’t the right way of putting it; contingent or invented might be a better way of getting at it. I think we realised very early on that it’s all invented and that, within certain practical and ethical boundaries, we can do whatever we want, so why don’t we do something that is, in itself, a kind of naïve experiment?

*Amelia Stein is a freelance writer and editor of The Blackmail.*