In the 1960s, Joseph Kosuth claimed that conceptual art would usurp the place of a number of other writing-based practices, such as literature and philosophy. It is now widely known that this bold claim was connected to his idea that the task of contemporary art had become to question and expand the definition of art in general; an undertaking that he argued could not be performed within the framework of historically established mediums.1 Conceptual art, in Kosuth’s terms, constituted a definitive break with formally differentiated modes of art making. It was not a medium, but a mode of enquiry into the conditions in which meaning is constituted in art, and also in language and culture more generally.

In accordance with Kosuth’s rejection of art’s specific forms, writing constituted a radical break with other artistic and discursive practices. But not just any writing. Kosuth imagined a writing of ideas, rather than writing conditioned by any of the fields to which it previously might have belonged, such as literature or poetry. It is of interest, then, that in a recent installation at Melbourne’s Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) ‘(Waiting for–) Texts for Nothing’ Samuel Beckett, in play* 2010, Kosuth employed passages of text from Samuel Beckett, an author widely recognised in the canon of modernist literature. As such, the work performs an exchange between the contexts of literature, theatre and the visual arts; a gesture that would appear to attest to the continued significance of differing artistic traditions.

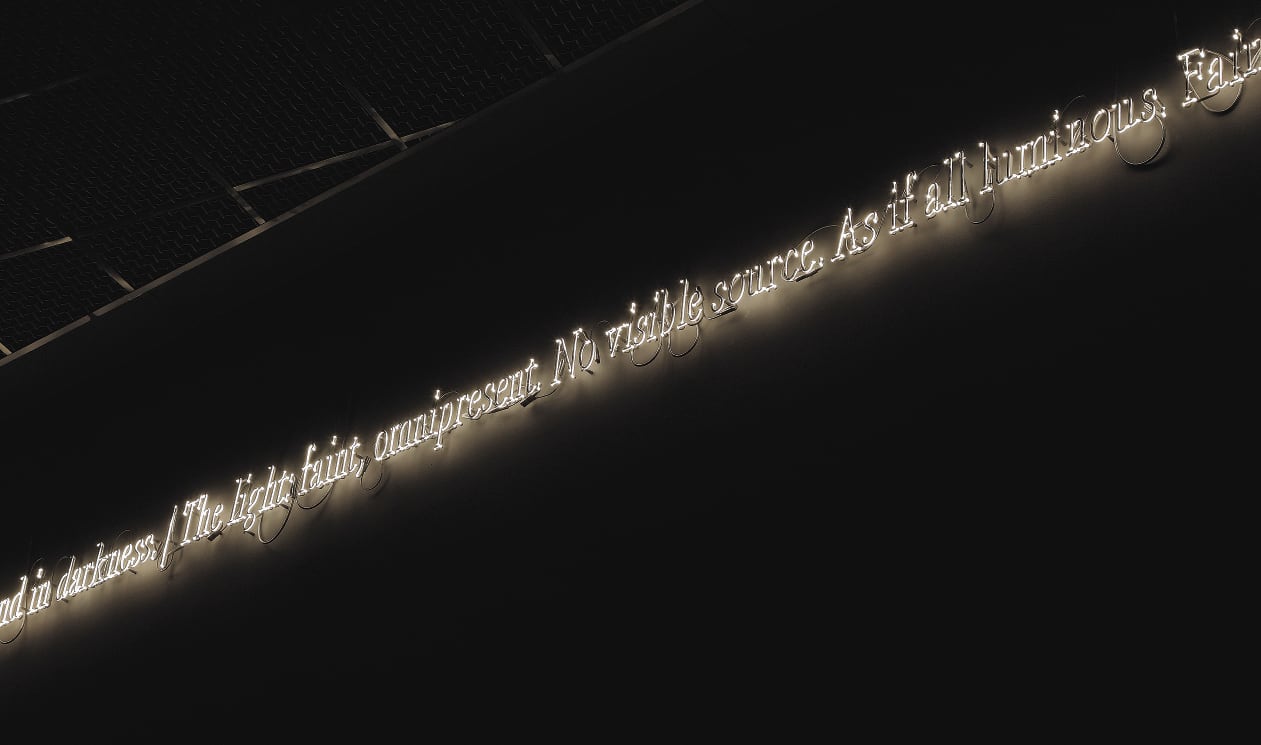

The ACCA installation consisted of a line of text in white neon, which ran around the four walls of the large gallery space at a significant height. By presenting Beckett’s literary writing in the context of conceptual art, an encounter is posed between these fields, and between the significance of Kosuth and Beckett’s status as ‘authors’. Although appearing as a single dialogue between the main protagonists of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot,2 the text also included fragments from a variety of Beckett’s works; the most conspicuous example being the line ‘You must go on, I can’t go[ on, I’ll go on’, which famously ends the novel The Unnameable.3 Kosuth thus presented a reworking, or rather a remixing, of Beckett’s texts. This could seem impudent, but this intertwining is already pre-empted by Beckett — many of his texts (such as the Texts for Nothing to which Kosuth’s title refers)4 make reference to, or even echo phrases from, his own oeuvre. The installation also included a small reproduction of a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon c. 1825–30, that apparently inspired Beckett to write Waiting for Godot. This previous exchange, between two moments in cultural history, found themselves reconfigured through Kosuth’s intervention. The intersection of these authorial ‘personalities’ allowed them to be inflected with a certain otherness, provoking a reconsideration of what each work or artistic mode might stand for. A relay was set up between the three artists as if they were protagonists in a play: it was no longer strictly possible to decide which aspects of the work properly belong to each figure.

Kel Glaister’s Attractive Futures 2010, exhibited at West Space as part of the group exhibition Aesthetics of Joy: The Infinite International of Poetics, curated by Bernhard Sachs and Brad Haylock, similarly positions itself between several authorial voices and artistic conventions. The work is a short novel, written (by the artist) for display in a visual art space. In the novel, a reflection of this event is staged: the main character is a sculptor who has received a commission to create the replica of a library and has taken it upon herself to re-write all of the texts that will be housed within. The novel’s narrative examines the way in which the sculptor tries to replicate various texts, from Don Quixote to standardised math textbooks, by treating them as formal systems. The text is thus also a quasi-treatise on art making or, as the novel’s subtitle puts it: ‘an unfinished fable on the Aesthetics of Joy, or the Joy of Aesthetics’.

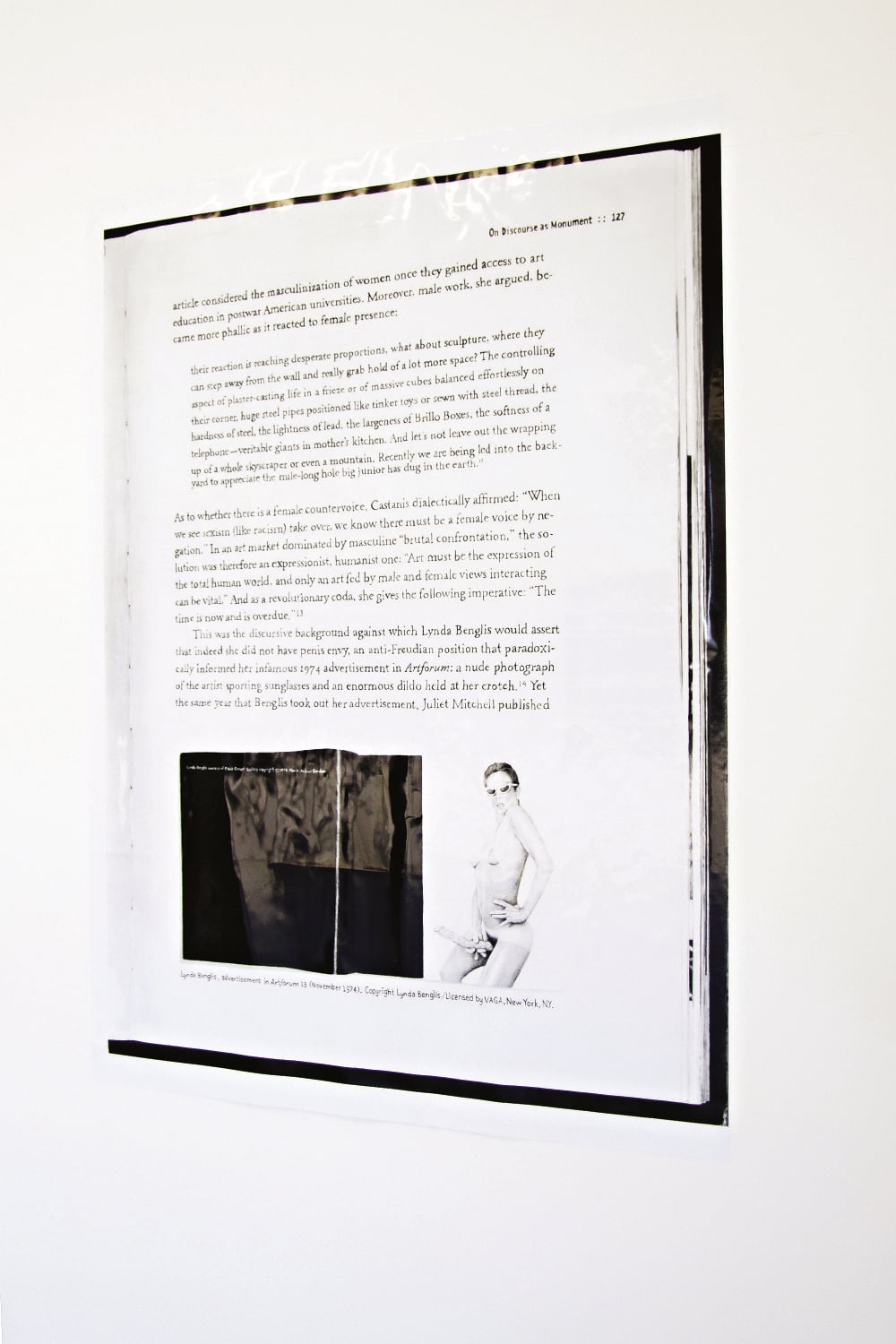

Kosuth’s citation of Beckett is unlike what we would expect to find in literary criticism, where one might endeavour to present a section of another author’s text transparently. By making the face of the neon tubing dark, the text was conveyed with a degree of illegibility; the words could only be effectively read when approached at an angle. Fiona Macdonald and Thérèse Mastroiacovo’s exhibition Access Restricted, at Melbourne’s Light Projects in April–May 2010, similarly engaged with citation; in this case between the contexts of art and criticism. Here, the page of an existing book was hand drawn by Mastroiacovo and reproduced as a poster displayed on the gallery wall. The page in question was taken from an essay by Juli Carson, which itself contains a reproduction of an infamous advert, originally published by artist Lynda Benglis in the journal Artforum in 1974.5 Benglis’s depiction of herself, naked and holding an enormous dildo protruding from her crotch, thus entered its fourth level of citation. One could clearly observe each of the duplicative layers framing Benglis’s image: its initial context in Artforum, the page of Carson’s essay which reproduced it as an illustration, Mastroiacovo’s hand-drawn reproduction of that page (made apparent by her slightly wobbling text) and, finally, the photographic printing techniques which converted this drawing into a poster. Meanwhile, Macdonald’s contribution consisted of another text, supposedly attached to the back of the poster and thus inaccessible to the viewer. This unseen piece of writing is perhaps the textual unconscious of the event; or an additional layer of text produced simply by attaching Macdonald’s name to the work as a collaborator.

Macdonald and Mastroiacovo’s work attests to the idea that the context of art is always heavily invested with discourse, and that the use of materials, techniques and personae contribute to the way that this discourse will be read. Tess E McKenzie’s work also employs writing to reveal the implicit conditions of art — in particular, the gallery or architectural space. For example, Hush 2010 consisted of the word ‘HUSH’ painted in tall white letters over a white gallery wall at Kings ARI, Melbourne. Here, writing indicated the implicit conditions of the white cube which, if not necessarily demanding silence per se, attempts to screen out all external interference, making the art object the focus of attention. Kosuth’s work of the 1960s is strongly associated with this sort of bracketing, in which a minimalist approach is employed in order to pinpoint a particular idea. This is evident in 10 Definitions of Nothing* 1969 (shown concurrently in the adjoining space at ACCA), where we are asked to ponder the attempts of various dictionaries to define ‘nothing’, an idea that can only be described through negation. In contrast, Kosuth’s recent work points to a recognition that the art context is never simply constant or neutral: the materials that are presented, such as Beckett’s writings, are read differently when they enter the visual art space; but at the same time are not completely disconnected from their previous incarnations as literary or theatrical texts.

Hush *also pointed to the way in which the art space, or the artwork, demands a certain type of behaviour from the viewer, which in turn orientates the process of interpretation. Kosuth’s installation at ACCA invited the viewer to move around a darkened and otherwise empty gallery, making apparent their role as a performer within the artistic process. As Kosuth puts it: ‘the text the viewer brings to a work organises what is seen. The production of that “text” has become a primary part of the artistic meaning-making process’.6 Far from declaring visual art the privileged site for text, as Kosuth originally envisaged, the works examined here employ writing as something that is always in the process of departing from one place, to be read according to the conditions of another. It is perhaps this heterogeneity of modes of writing at play within the site of the visual arts that continue to make it a compelling medium.

Stephen Palmer is a Melbourne-based artist and writer.

Photo credit: Christian Capurro