If a work of art was a woman’s body, could psychoanalytic theory serve as her girdle? A gal such as myself never overlooks an opportunity to exploit mundane activities for their metaphors, and I was definitely washing underwear when I realised I could write ficto-criticism. It was 1983 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada and I was an insignificant intellectual who preferred artists over psychoanalysts for friends.

Psychoanalysts in Toronto did not consider psychoanalytic theory to be the equivalent of a collage or a sculpture or a movie, did not consider psychoanalytic theory to be a work of art. Psychoanalytic theory was considered a device for prying open psyches. Psyches were thought to be a system that psychoanalytic technique could adjust.

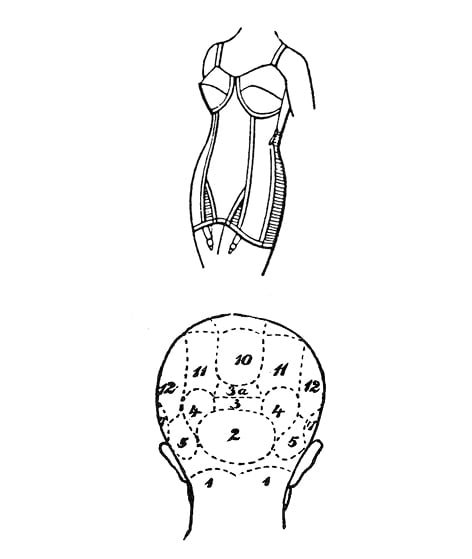

Psychoanalytic theory was considered to be like a foundation garment: it could not remake a psyche, but it could shape it up. Or was psychoanalytic theory more like a silicone breast implant, shaping up the psyche from inside?

Ficto-criticism would be based on psychoanalytic theory, but if the theory was too skimpy here or there I’d just stretch it. I found object relations theory as it was presented by D W Winnicott to be very stretchy. Ideas in Winnicott’s book Playing and Reality 19711 supplied almost all of the prototypes for ficto-criticism. Winnicott crafted numerous ambiguous and paradoxical ideas, and of course I could exploit his assumptions. There were also his fanciful hypotheses. Yet none of his speculations conjured images or metaphors. It is impossible for me to imagine art that is devoid of imagery. So I decided I must dramatise Winnicott’s terms. To do so would imbue them with relevance to art. A psychoanalytic professor, for example, could have pronounced ‘the potential space between the subjective object and the object objectively perceived’ to be an explanation of audience receptivity to art.2 Instead I coined ‘the amenable object’, definitely a version of Winnicott’s term.3 But it didn’t really explain anything. It had implications.

To me it seemed silly to pretend I could delineate how a collage, for instance, delivers a message.

Instead I would write a text that seemed to me to be analogous to the collage. When someone looks at the collage, for example, they’d be in a situation where they could conjecture what the collage connoted or alluded to. If someone read the ficto-criticism in the exhibition catalogue they’d be in a situation where they could conjecture about allusions to the collage(s). The ficto-criticism would be amenable to conjectures. If amenable to conjectures, ficto-criticism would lend itself to provisional interpretations, lending itself to provisional interpretations of the artwork as well. Ficto-criticism would not be a precise presentation of an idea any more than a painting would be a precise presentation of an idea. Ficto-criticism is a story that seems to refer to what the artwork refers to. Ficto-criticism seems credible yet, at the same time, uncertain. -Readers could rely on their own judgment call — their own inventiveness, store of knowledge, wishes and beliefs — for what is verifiable or not. If, that is, they take the time to look again at the artwork with the ficto-criticism in mind. And vice versa.

For instance, ‘The Gift of -Paranoia’ was written for an exhibition that in-cluded drawings (some directly on the walls) vaguely resembling floor plans. There were three stolid tables supporting assemblages that looked like rough architectural models for neighbourhoods overshadowed by elevated freeways. In the following excerpt, features of the ficto-criticism correspond to imagery and apperceptions (italicised) in the artworks.

The paranoid toddler [who] grows into a paranoid adolescent … develops into a youthful paranoid adult who attains the height of success as a paranoiac in her late forties (Most paranoid people are females, whose paranoia is subtle, intellectual and often remains a personal secret; grandiosity is what betrays the male paranoiac, who consequently will more often get medicated.). As she ages, the paranoiac’s delusions become more conceptual.

If the teenage girl who is paranoid doesn’t tell anyone about her proto-paranoid play as a toddler, you might think the girl developed her delusions only when she entered adolescence. An example of such a teenage paranoia would be the complex scheme concocted in 1978 by the sixteen-year old Miss Crystal Uggams. Every Christmas Crystal would travel with her parents down to Sandville, Florida to visit the grandparents. Crystal’s maternal grandparents lived in a Race-Lite trailer in a gated RV-mobile home park called ‘Wilderness Metropolitan Villa’. Relaxing by the swimming pool Crystal began watching a group of five male employees wandering around with shovels and acting like grave-diggers. She had already observed how the paths of Wilderness Metropolitan Villa conformed to a grid system that was identical to the pattern of headstones in the military cemetery where her uncle was buried. Crystal lay awake nights correlating the clues she had gathered during the day, clues that added up to a dead-spy hunt. The grave-diggers, she reasoned, were evidence that Wilderness Metropolitan Villa had previously been a burial ground…4

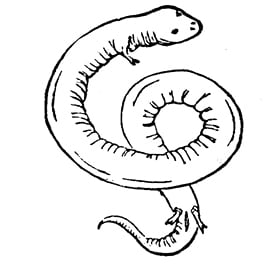

Aren’t amphibians wondrous? I would love to watch a congo snake slithering in its habitat, but I never have. So I don’t know whether congo snakes have always been famous for curling themselves into a Greek lower-case delta. It is possible that taxidermists twist dead congo snakes into a delta position for the aesthetic effect. Is the former more authentic than the latter? I do know when it comes to ficto-criticism (or performances as a psychoanalyst interpreting Western culture) authenticity is the audience’s problem. I can’t tell the difference between authentic and fake. It’s all fake to me. Evocative ficto-criticism (like the good doctor dispensing conjectures from onstage) could seem an authentic tale to those who long for truth. Or seem like a shameless fabrication to those who long for enchantment. To those who aren’t seeking satisfaction ficto-criticism will appear to oscillate merrily between genuine and phoney. The authenticity of the ficto-criticism written for Toronto artist Joanne Tod was meant to be questionable:

It would be only natural to assume that I am the subject of the painting Miss Lily Jeanne Randolph, as my family nick-named me Lily Jeanne, and only my closest friends know this. Ms Tod is, of course, one of my closest friends. Ms Tod needs me as a friend, but as an art critic she does not really need me. I am only one art critic among many who might be similarly paid to write about her art. But wouldn’t you suppose that if I am involved in her life and portrayed in her painting, I could write something about her work that is deeper than what others who are paid might write? I might know something unique, something personal, even something secret.5

I think of my praxis as a branch of the deadly nightshade. To look at it, to stand in a clump of such blossoms, the flowering organic sense of purpose is enticing. Modernist art critics, or art historians dedicated to scientific objectivity, had immediately recognised ficto-criticism as poisonous. Like the Greek philosophers who encountered Sophists in 500 BC, modernists would deny that their so-called objective analyses were no more (and no less) than a writing style, an acquired rhetorical expertise. In an effort to duck any discussion of privilege and legitimacy modernists had at first snubbed ficto-criticism as mere post-modern fashion.6 Ficto-criticism was also decried as ‘amoral,’7 ‘narcissistic,’8 ‘immature’9 as well as the expressionism of an unschooled ‘eagerly overachieving’10 interloper.

Students in art-writing courses also recognise ficto-criticism is poisonous. Students will listen carefully to the object relations psychoanalytic tenets upon which I base a ficto-criticism practice; and they immediately perceive that, as a paying career, ficto-criticism is suicidal.

For me what seems poisonous within the flower of ficto-criticism is Doubt. Actually, then, a jalapeña pepper plant is a more simpatico metaphor. Although mischievous, the doubt intrinsic to ficto-criticism is intended to be ethically fruitful. For me, doubt is not the same as scepticism. Doubt implies an existential predicament (Scepticism is an intellectual stance). Deftly composed ficto-criticism just might accentuate how the consequences of representation are its effects, intentional and unintentional effects. If only for the duration and attention taken to read a ficto-criticism text, readers might become alert to its effects upon them, alert to the doubt provoked. Just maybe the power of representation would seem worthy of serious consideration. The following excerpt is offered to illustrate how ficto-criticism provokes doubt (if indeed this excerpt does), alerting (if indeed this excerpt does) its readers to the politics (or is it the ethics?) of representation:

I like to smoke tobacco. The smoke of a freshly-lit cigarette is existential. I am careful not to pull in the smoke too fiercely; the intensity of the drawing-in calibrates the temperature of the smoke. Not that I inhale the warm smoke into my fragile rosy lungs. That would be suicidal, and in spite of my Death Wish, I am not suicidal. Speaking of Death Wish, everybody has one. It’s just a matter of one’s relationship with it.

I have to reckon with my Death Wish when I get into a vehicle. I know all the statistics for dying in a car crash, and I have witnessed overturned passenger trains twisted beside the rails. Airplanes are safe — until you are strapped in one during a flaming nose dive.

Whenever I enter one of these vehicles I have to acknowledge that I am giving the edge to my Death Wish. Just because these technological devices are intended to facilitate efficient travel, intentions count for nothing to a Death Wish. The Death Wish is ready and waiting…

If you have been finning under water, or recovering from an acute episode of asthma, or striding across an expanse of land as far from urban trash as you can possibly get, there is a pleasure of inhaling the sky. Inhaling a lit cigarette is an exaggeration of this memory, a psychosomatic memory that invokes clouds and the zephyrs, The Holy Spirit, the Breath of Life, the inspiration of the Muses.

A cigarette is also one of the technologies of pleasure. Marshall McLuhan would have said that as a technology it extends the power of the human body. Cigarettes, in McLuhan’s terms, enhance the power of the thorax, enhance the power of the ribcage, lungs and diaphragm to — to what? — the cigarette, the ‘understood medium: the extension of Man’, enhances the power of memory, the power to evoke religious and philosophical and mythological imagery.

If, on the other hand, a cigarette is simply one of many materialisations of the twenty-first century’s most prominent ideology (called The Technological Ethos), then the function of the cigarette (to offer Canadian Classic cigarettes as an exemplar) is to inject 14–33 mg tar, 1.4–3.2 mg nicotine, 14–33 mg carbon monoxide, 0.061–0.14 mg formaldehyde, 0.12–0.23 mg hydrogen cyanide and 0.047–0.089 mg benzene quickly and efficiently, with minimal margin of error, into the human bloodstream.

The effects of this inhalation are a combination of poisoning and existential consciousness. It’s up to smokers to discover the amount of poison that induces the best consciousness.11

Dr. Jeanne Randolph has been writing ficto-criticism for visual arts exhibition catalogues since 1983. Her five published books also present ideas on psychoanalytic theory, philosophy, technology, advertising and pop culture.

ism, unpublished MA thesis, York University, Ontario, 1993.