This title, "Editorial Feelings", rips off the recently published Curatorial Feelings, a collection of texts by Eloise Sweetman and co-edited by Jo-ey Tang in 2021. Tang’s editorial introduction proposes that Sweetman calls ‘out her “curatorial feelings” juxtaposes and unites the two modes of engagement: as a curator and as a sentient being.’1 This sentiment produces an amusing image: a sentient being (worker, viewer, critic, etc.) in a gallery, dowsing for all the ‘curatorial feelings’ bound up in feature wall colour choices, ostentatious signage decals, inaccurate sketch-up diagrams, moments of tired exchange between overqualified and underpaid install techs, barred from sublating or expressing their own (curatorial) feelings (and why should they anyway).

Admittedly, I didn’t spend long with the book — skimmed through a friend’s copy and pirated some pages with my phone — but I was curious and cynical about the phrase 'curatorial feelings’ immediately. My pirated pages don’t contain enough information to properly reconstruct the context of the following quote, but here Sweetman elaborates her titular phrase ‘Curatorially speaking, I am a grey-white moth spinning’:

When I work, I like to move around the room. Often I pretend to be the audience and act out coming into contact with art. I can’t do it any other way. I have to approach art-making and curating bodily.2

This strikes a chord with the “editorial feelings” that I’m attempting to describe here: sitting in a library or at a bar with red pens and highlighters dissecting through a practice (writing or reading) which was previously so private and mental. Pre-eminently embodied, yet unlike Sweetman’s idea of acting-as-audience, the editor is always the reader and the writer, but in a depreciated form, insufficiently inhabiting either role. Editorial sado-masochism? Right on.

That being said, this only happened once or twice during my un Extended editorial residency. Editing was mostly conducted through Google Doc track changes, isolated from the author, and maintaining a fenced off garden of scholarly privacy. I relished this disembodiment. My body doesn’t have to be “there” to work because it's also here: working. The body persists in disembodiment, it dirties my trackpad and it squints over misplaced commas and accidental double spaces. Is this an editorial feeling or stationary fetishism? In either case, I really enjoyed asking writers I admire to write, and was happy it was financially and practically reconcilable for both of us. Maybe that’s enough of a feeling.

When you get your foot in the door is it a feeling or a desire? Assuming the answer is both, let’s also assume the feeling is painful, numbness, throbbing. Playing a game of catch, hoard and release with opportunities in the arena of relentless neoliberal conditions can feel something like a corn on your heel or a toenail growing into the soft flesh that surrounds it. Nonetheless, a foot in the door inflames desire in the heart, and as such, pain is ecstatically joined by shame. Georges Bataille famously opined on the human-all-too-human quality of the big toe. This perverted digit juts rigidly out of the human foot, which for Bataille is:

commonly subjected to grotesque tortures that deform it and make it rickety. In an imbecilic way it is doomed to corns, calluses, and bunions, and if one takes into account turns of phrase that are now only disappearing, to the most nauseating filthiness: the pleasant expression “her hands are as dirty as feet,” while no longer true of the entire human collectively, was so in the seventeenth century.3

My conjecture here — with aim at stoking the editorial desires felt during the residency — is that Bataille’s foot-fetishist nostalgia for a muckier time ought to be rewritten for our contemporary filth paradigm.

The human toe is no longer the basest human part. It is the human smartphone; the primary interface used to read the digitally published writing I commissioned last year (and everything else oozing out of this planet). The phone is the most human of human parts, a petri dish of bacterial advertisement, virality and attention parasitism. Seventeenth-century trench foot is replaced by twenty-first century digital platform tapeworms. Bataille: ‘Man's secret horror of his foot is one of the explanations for the tendency to conceal its length and form as much as possible.’4

While our phones contain perverse multitudes, kept “private” behind facial recognition and hidden app folders, my approach to digital publication (and most things, to be honest) is to not shamefully hide behind this secret horror, but stick my head in the swamp, delve into the near-ecological level of collecting ‘stuff to read’, as well as embracing the many ways ‘to read’. Open that tab and leave it open! Just try not to forget to return, or at the very least chuck it in a bookmark folder labelled ‘TEMP 2023’. The solar anus brings ennui along with something decent to scroll through.

I don’t mind identifying with the notion “un Projects goes west”. Will my year of editing and commissioning articles, along with Boorloo-based Bahar Sayed and Gemma Weston’s volume 17 of the print publication, un Magazine, join the history of “goes west” projects produced by east-coast artist-run publications?5 I’d be remiss not to mention what I’m calling “stayism”: the phenomena of west-coast living folks actually “staying” west, which is more of an attitude than anything (maybe you can “stay west” while enjoying lengthy international sabbaticals, or at the very least, coming back for the NYE beach raves). Not sure what to say about this phenomenon. Although, reading through Semaphore — exemplary of arts writing and publishing during heightened stay-istic pandemic conditions — might provide a vague picture of the stayism mood I’m describing here. As much as I impress upon anyone that will ask about the importance of recognising the inherent death drive of all ARIs, I will also admit to the pleasurable principles of awkwardly finding your feet in ARI work: collaborating, gossiping, having art crushes, embracing pathos and engendering meaning.

Being un Projects’ 2022 Editor-in-Residence did afford me a modicum of longitudinal ambivalence. Instead of buckling down into learning what an “editor” is, I found myself falling into old “boundary collapsing” habits, at least in terms of exploring from the outset the ways in which genre, form, format and identity could be explored and challenged. The resting state of interdisciplinarity is an all too familiar condition to creatives working today, reflected in the awkward jostling of roles in bios (an editor-critic; artist-researcher; performer-installer, and so on). We can call it “hybridity” and in doing so, invoke a feeling that is somewhere between finding-your-feet and feeling-like-a-pseud. How clever of me to mention hybridity! As Felix Bernstein elaborates:

The most exceptional artist-critic can seamlessly combine banality and transgression, trespassing temporal and disciplinary norms, while still reaping the conventional rewards of the market. But to sit in a sovereign seat of charismatic exemption is a double-edged sword. And the risk is producing too perfect a genre, one that is too exclusionary.6

There is a degree of auto-humility built into this enterprise, and so should there be. If there is an editorial feeling at all, it is not ever really feeling like an editor in the first place, but more like a stock cube of roles and responsibilities, ready to be dissolved into the whatever-soup.7

Many of the writers I commissioned seemed informed by the “irony versus sincerity” paradigm of peak millennial zeitgeist. While it brings up the bile of our collective post-internet, this bad taste is still worth finding notes in, lest we mouthwash and hand over our editorial feelings to marketing boilerplate. Being sincere on the internet is the sui generis editorial feeling. Is it hopeful to cling onto the poetry of self-exposure? I recall Sofia Leiby’s essay where she posits that ‘[m]aybe, then, the Internet is not a place for hiding, for irony, coldness and nostalgia, but a place that makes sincere, open, warm, and human gestures in art.’8

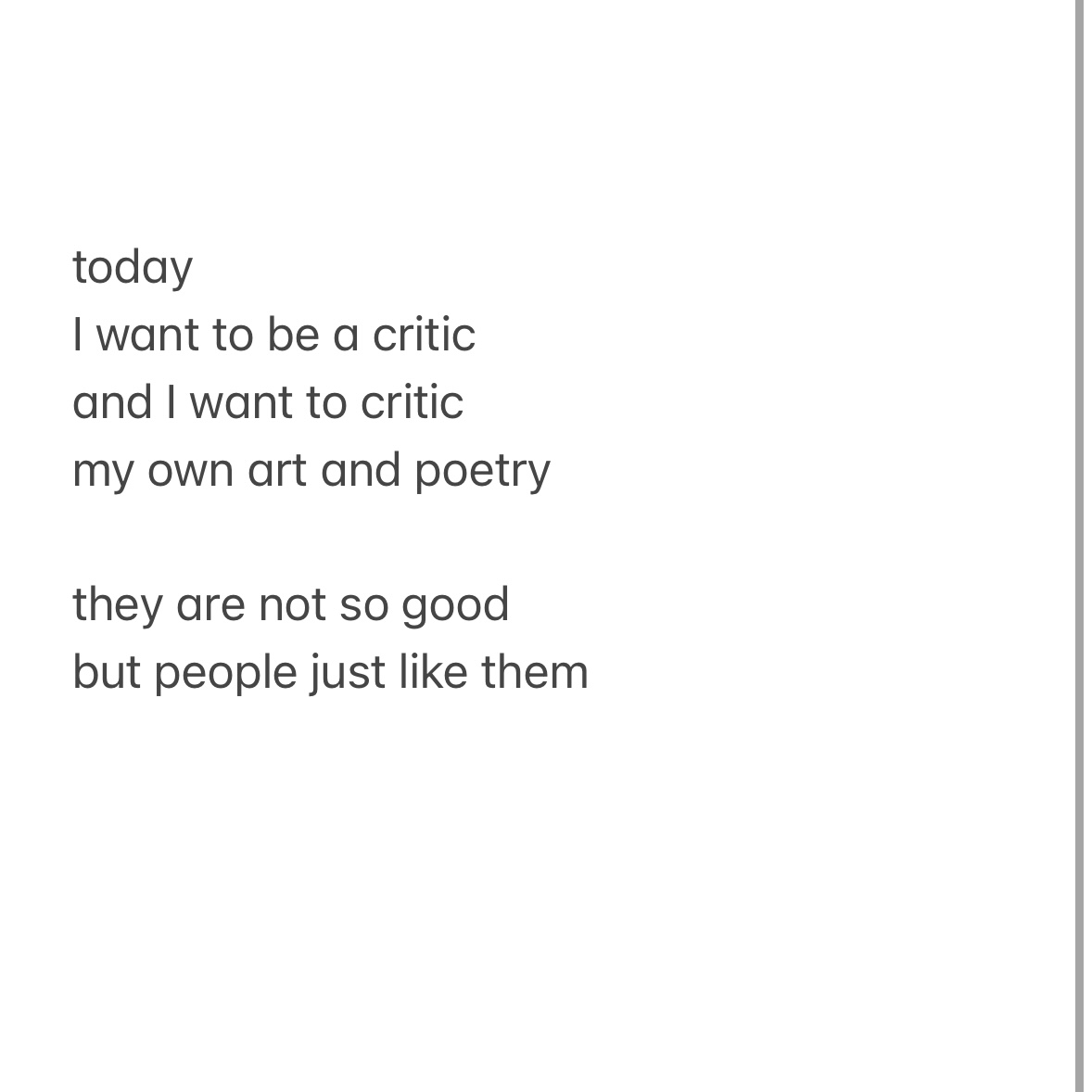

Who can say? I have often found myself posing this question in response to the prolific and poetic activity of Chunxiao Qu. Qu’s Instagram bio (@she_andherdog) identifies the artist as an ‘art critic and comedian’. More hybridity. On the grid, Qu posts a variety of content, including a continuing series of iPhone Notes app poems. Qu’s posts reveal traces of the interface itself. Tensions between the ironic and sincere dissolve in the easy extensivity of the Notes app. The editorial feelings here are near totally disembodied, feed-ready, yet totally base, all-too-human. At times you can see a yellow highlight, or a red squiggly line denoting a spelling error when the author includes her handle.

In July 2022, Qu produced a series of thirty-one “tributes” to conceptual artists. Alongside daily Instagram posts, the series was exhibited as Copy, courtesy of 99%, a gallery project directed by Chelsea Hopper and housed in the Nicholas Building, Melbourne. Qu’s exhibition statement attributed the procedural format to American curator Seth Siegelaub’s One Month which gave thirty-one artists each one page to work on, representing each day in March 1969. Siegelaub referred to One Month as a ‘situation available for people to use’ and explains that ‘a lot of people did great things but there was also absolutely terrible shit in there. But I wasn’t really concerned about that. That’s their responsibility.’9 Are these editorial feelings in bad faith? Navigating what is great and what is shit could be enforced as an editor’s responsibility. Instead I’m interested in what ways this is negotiable. What is good and what is shit is not a prescription; it's a mood or an intuition or, in other words, a feeling that matters. Qu’s Copy taught this lesson diurnally.

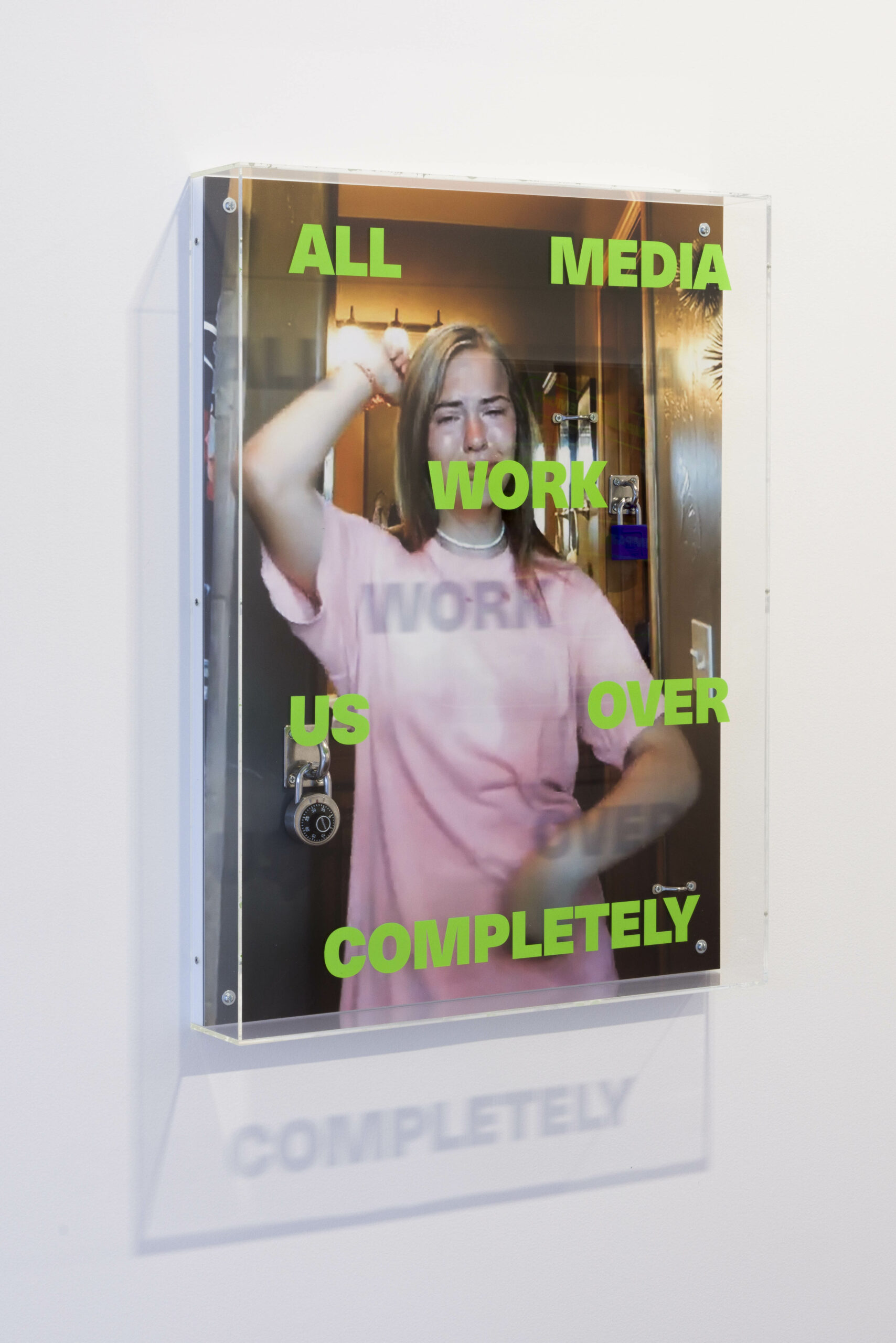

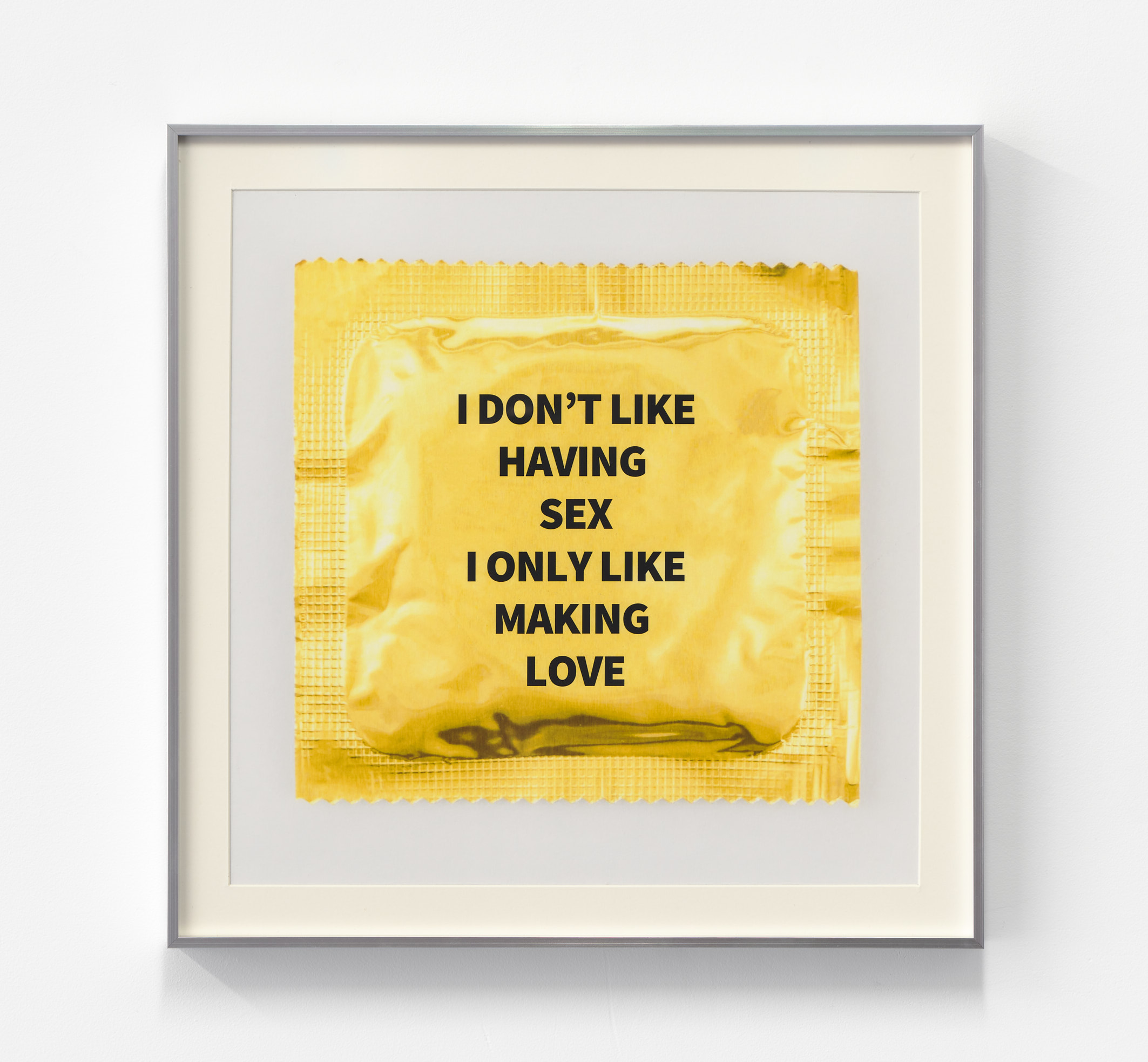

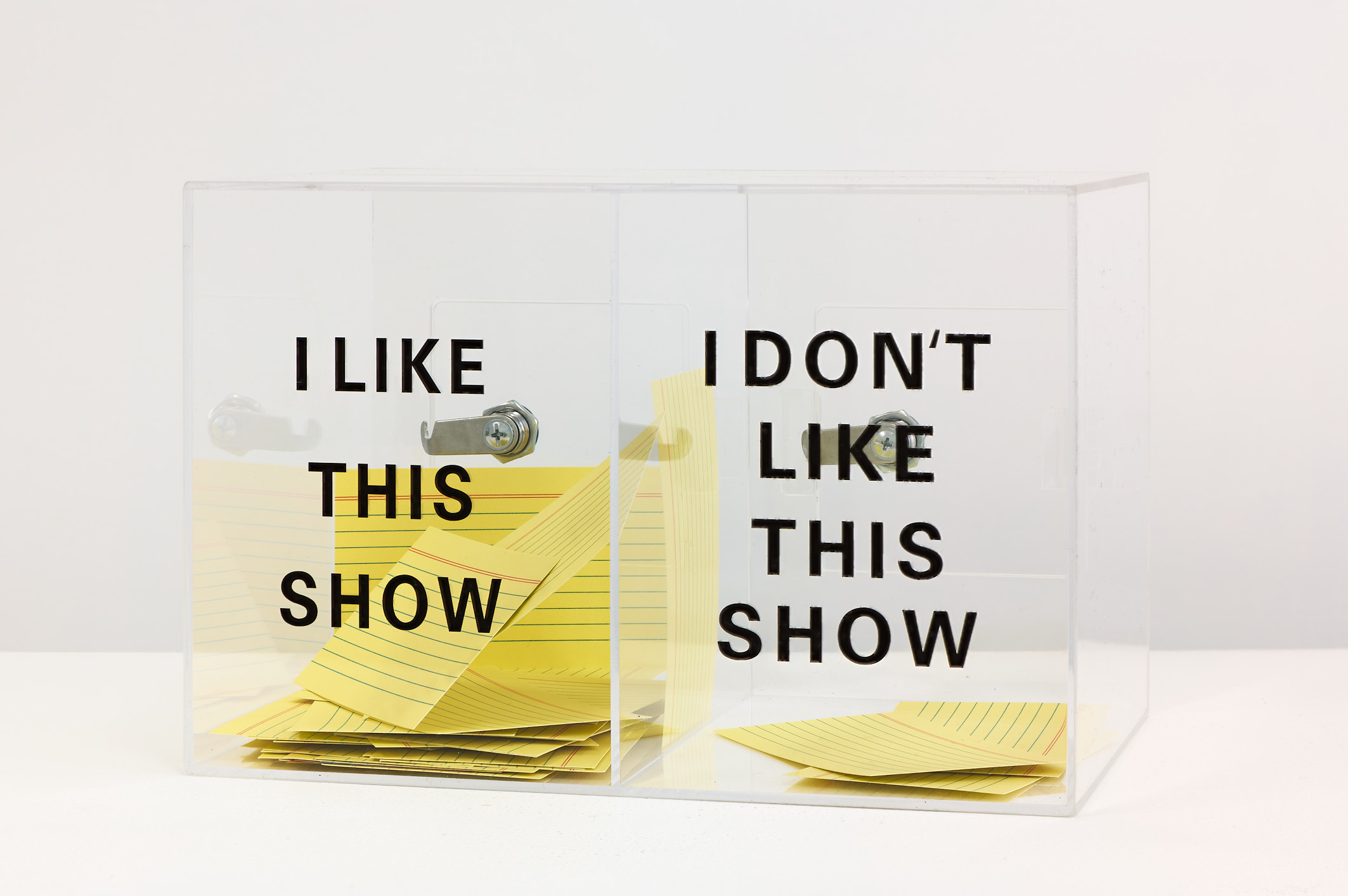

Beyond great and shit, Qu’s conceptual art appropriations reflexively produce their own "situation for use", based on the history of previous uses. The word “tribute” offers an important guideline: if the works referenced are good or shit or somewhere inbetween, the tribute renders them all excellent subjects for Qu’s poetry. In the gallery, a tribute to John Baldessari repeated in Bart Simpson blackboard punishment style ‘I will not make any boring art either’. A Jenny Holtzer condom reads ‘I DON’T LIKE HAVING SEX I ONLY LIKE MAKING LOVE’. Given 99%'s meta-curatorial focus on populism it was appropriate to find two ballot boxes respectively labelled ‘I LIKE THIS SHOW’ or ‘I DON’T LIKE THIS SHOW’. Copy luxuriates in an editorial feeling most tantalising: your work is my work, it’s our work.

Twenty twenty-two. A year of editorial feelings, sure. I felt it mostly in the feet, a bit in the heart and a lot in the brain. Whether the digital nature of this work is embodied, disembodied or neither is an issue that cannot be settled here, and nor should it be. My gut tells me that reading, writing and publishing remains a salient and precious activity, one that needs to bear through feelings of queasiness in order to weather the turbulent conditions that show little sign of settling on the horizon.

I’ll end with a retrospective editorial summary of the articles commissioned during my residency, and with a brief note of my sincerest gratitude to the authors I worked with for their contributions, and to un Projects, for the opportunity. My first commission asked Nancy Mauro-Flude to leverage a lunar perspective on the moon’s new fury. Aisyah Aaqil Sumito delved into the bodily passages of Meatus. Annika Moses tuned in and dropped out to Bridget Chappell and Debris Facility’s residency at Cool Change. For Quishile Charan and Zaiba Khan’s exhibition Angna Mein, Julia Rose Bak seeded the memory and potential for interconnectedness.

My long time co-conspirators Lévi McLean and Chandler Abrahams indexically blew the lid on To companion a companion. Karl Halliday and Channon Goodwin discussed artist-run organisation Composite. Jessyca Hutchens examined the emotional, spiritual and historical registers of Curtis Taylor’s Ruu. At Disneyland Paris, Mitchel Cumming exhibited Wardrobing, which put forward the idea of the “temporarymade”, analysed by Francis Russell in his review. For the last commission, jemi gale wrote a poem for the late Sab D’Souza, which accompanied There is No Fire.

Paul Boyé is a writer and researcher based in Boorloo. They were the inaugural un Extended Editor-in-Residence in 2022, and after that, continued as the Managing Editor of un Extended.