In 2012 the Aboriginal Tent Embassy will commemorate forty years of Indigenous political activism at its Canberra site. Set on the front lawn of what is now Old Parliament House (OPH) and surrounded by monolithic buildings, such as the High Court of Australia, Treasury offices, National Gallery of Australia and National Library of Australia, the Embassy is dwarfed by its neighbours. Significantly, the Embassy is situated within the Parliamentary Triangle, with the Australian War Memorial, Defence Headquarters and New Parliament House at each of its axes. Despite its intimidating environs and challenging history, the Embassy has never moved from its original location, nor has its residents deviated from their cause. In fact the site remains as important and sacred, if not more so, than any of these other heritage-listed and historically significant buildings located at the heart of Australia’s political and democratic centre.

The ephemeral quality of the Embassy and its structures and the transient nature of its residents by no means diminish from the significance of the location or the monumental importance the site holds for our Indigenous population. From the Embassy’s tumultuous beginnings on 27 January 1972, when it spontaneously grew from a single beach umbrella erected by four Aboriginal activists in front of the then-provisional Parliament House, it has come to symbolise the fortitude of Indigenous Australia and acts as a meeting place for elders, leaders and activists. In contrast to what is commonly defined and appreciated as an official ‘embassy’, let alone ‘architecture’, the site should be preserved and valued for the same heritage reasons as other buildings and institutions within its vicinity. More interestingly, what does it mean to have this site heritage-listed or legitimately recognised for its historical importance when no permanent architecture, in a physical sense, exists?

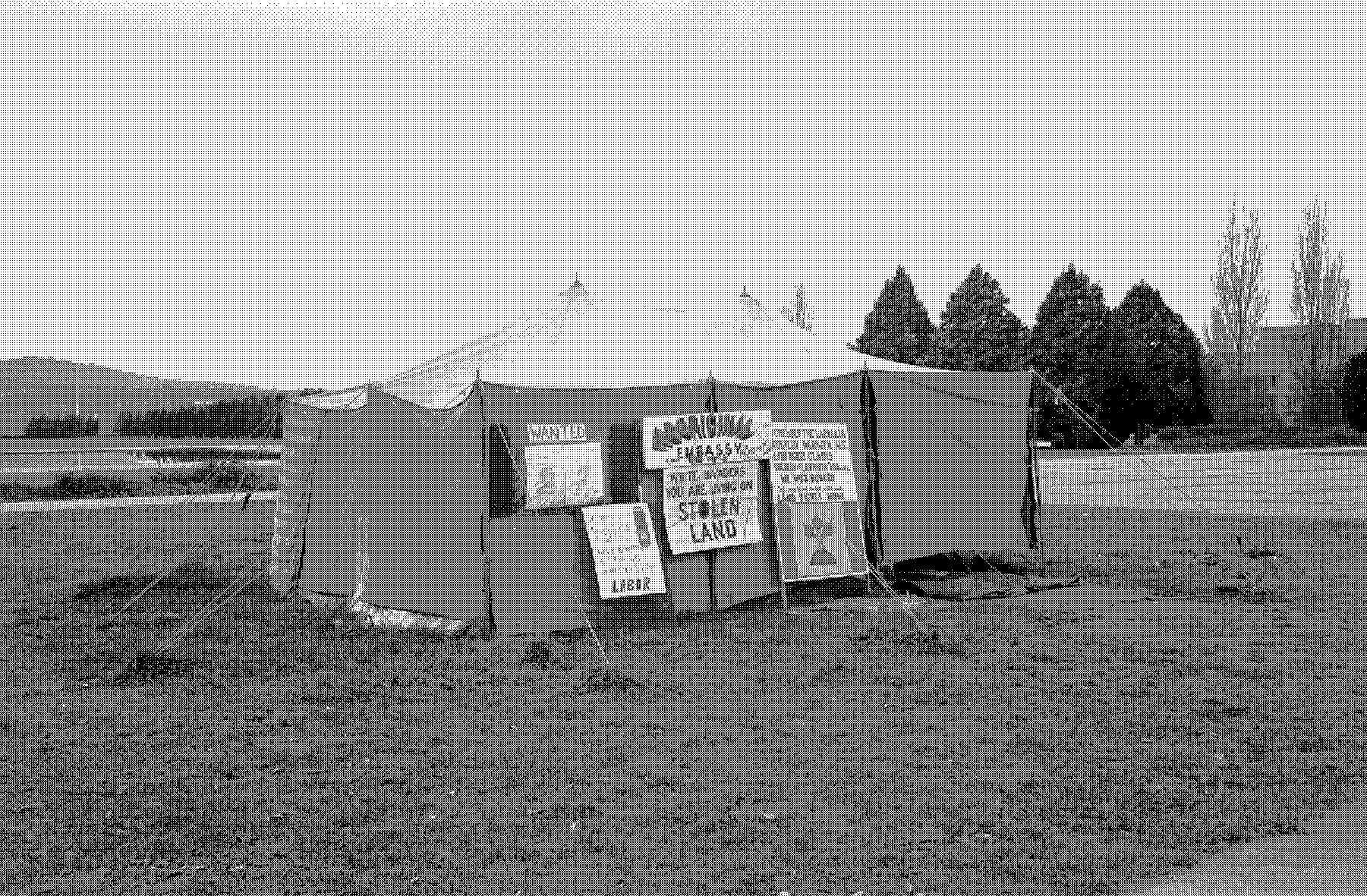

In its current form the Embassy consists of a scattering of tents and tarpaulins pitched beneath a grove of trees lining either side of the lawns outside OPH. The campsite has evolved in various forms and configurations dependent on the number of residents living at or visiting the Embassy. In reality, its physical architecture is a haphazard mix of recently purchased, off-the-shelf, synthetic and canvas tents in varying states of decline, in addition to a shipping container, Porta-loo, caravan, barbecue area and a large, circular ceremonial ground. Today, the Embassy cannot be missed by visitors and tourists to the national capital, and is a visual wedge driven into this orderly, almost clinical, landscape and surrounding architecture within the Parliamentary Triangle. From the brightly painted shipping container adorned with colourful political commentary to the smouldering Fire for Peace and Justice at the centre of the ceremonial ground, the site sits in stark contrast to the austere, symmetric, matte white, stripped classical style of OPH situated behind.

OPH is a significant landmark in Canberra. Designed by John Smith Murdoch, the first architect officially appointed to the Commonwealth, the building is modest in scale and form and was heavily influenced by British colonial architecture of that period. This style was favoured for much of Canberra’s government architecture built between the world wars. OPH was also a major component of Walter Burley Griffin’s meticulously planned layout for the capital, and forms the apex of the Parliamentary Triangle. In particular, Griffin’s design sought to demonstrate the symbolic relationship between the legislative, executive and judicial components of government and their hierarchy. Set against this staid backdrop — in fact right on its doorstep — is the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.

The Embassy’s physical appearance has been described by many as a political comment and visual reminder of the current living standards and conditions faced by many Indigenous Australians. The Embassy does not present a romantic notion of life in the outback, nor is it publicised as a populist tourist attraction. As the ‘architects’ of the Embassy will attest, it ‘physically reflect[s] the typical housing of Aborigines in Australia today, and one which [has been] strategically placed under the noses of Australian politicians’.1 It is as though a little slice of reality from any one of the makeshift camps on the fringes of Australian society has been relocated to the capital. The site creates a discomforting visual presence which reminds governments and citizens from Australia and elsewhere of a continuing Indigenous underclass with more health problems, less education and a much shorter life span than other Australians. The Embassy accepts its dual roles: it not only recreates the abject poverty of fringe dweller camps, but is respected as an ‘official’ embassy. In effect, it is both an embassy and its antithesis. This clever ruse highlights the dispossession and lack of representation for our Indigenous population yet, paradoxically, also has the power and authority to represent its constituents.

[The Embassy] was a display of symbolism at several levels, being simultaneously a comment on living conditions in Aboriginal Australia, on the question of land ownership (of this particular piece of ground as well as other parts of Australia), on the relative status of indigenous people in a city dotted with embassies, and on the avenues of protest open to the otherwise (often) silent minorities in Australian society.2

The campsite’s ephemeral quality has also been said to reflect the delicate touch Indigenous populations have had on their land, despite almost 40,000 years of living throughout this country. Their nomadic existence, moving with the seasons and in sync with food availability, necessitated shelter that could be erected, dismantled and transported with ease. Ironically, the Embassy’s synthetic and canvas tents allude to similar design and construction principles invented and developed over millennia. Unlike most culturally significant buildings and monuments in Canberra, the Embassy has not been designed or built for perpetuity. Rather, the significance of the site will outlive the ‘physical’ architecture itself. As long as the site is populated and inhabited, the basic principles, ideals and right to free speech it represents will also live on. Long term caretaker and one of the Embassy’s original ‘architects’ Isabella Coe vows to keep it going as long as she lives: ‘While there’s a need for it to be there, while ever these things are happening to our people, while ever our sovereign rights aren’t recognised, I’m not moving anywhere’.3 As she elaborated at a recent symposium:

The site stands for solidarity, stands for a principle, no surrender. It is a symbol, without physicality. It is a sacred site, a site for remembrance, a site of significance … but, it is not just a site, it is also an idea. You can’t physically move this site from Old Parliament House to the new one; nonetheless it follows our decision makers. It is a place for all Australians.4

Unfortunately, the site has not always been a ‘place for all Australians’ and was torn down on 20 July 1972, less than six months after it was first erected. Eighteen occupants were arrested and many others were forcibly removed under draconian laws that made it illegal to camp on Crown land. Police acting on orders from the McMahon Liberal government in power at that time stormed the site removing and confiscating any physical structures and dispersing the activists. However, despite the intimidation and, at times, violent clashes with the authorities, the political activists, peaceful demonstrators and student groups rallied together and quickly erected a new embassy to replace the first. Their second attempt to resurrect the Embassy was short lived and it was again torn down within days by several hundred police officers waiting in anticipation. The documentary film Ningla A’ Na 1972, directed by Allesandro Cavadini, beautifully captures the absurd moment, almost comical had it not been true, when scores of police emerged from behind OPH in military-like formations in an effort to overawe and overpower the activists gathering at the site.5

As the violence escalated and subsequent local and international media coverage intensified, so too did the public’s anger over the authorities and government management of the situation. One activist Gordon Briscoe recalls: ‘the violence as it was portrayed on TV … was on a par with the Vietnam images, on a par with the anti-apartheid images’.6 In hindsight, the Embassy marks the site of recent violence against our Indigenous population and it became visible before our very own eyes. There was no ignoring the facts. It signalled a turning point in our nation’s history; Australians were no longer able to avert their gaze to such issues. We were forced to confront our prejudices and past wrongdoings.

After two removals of the embassy, the essential issues of land rights and the right to mount such symbolic, creative and non-violent protest, remained unresolved. The tension between the embassy and all it stood for, and all the forces of authority, had not diminished since 20 July. The question loomed: was there to be a third, even larger and more violent, protest in front of the seat of government?7

The question that Scott Robinson poses is problematic. While a third and final Embassy was rebuilt and has endured at the Canberra site to this day, the issues raised remain unresolved. Indigenous Australians still suffer from appalling health problems, poor living standards, high rates of unemployment and welfare dependency, suicide, deaths in custody, substance abuse and an ongoing lack of recognition for land rights and sovereignty. Next year we may celebrate — or rather commemorate — the Embassy’s fortieth anniversary, yet it should also come as a reminder that there is much to be reconciled. Sadly, the fact that many of the Embassy’s original ‘architects’ and activists are now middle-aged and still struggling to be heard on issues they raised as teenagers is a shameful indictment on Australian democracy. While the Embassy should be conserved for future generations and the site’s historical significance officially recognised, ironically this may never require Australian Heritage Council approval. For as long as these issues remain unresolved, we will be constantly reminded of them by the visual presence of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.

It might be almost four decades since the ceremonial fire was lit and the distressing message from Australia’s Indigenous population was poignantly hand delivered to our parliamentarians. Nonetheless, the embers continue to smoulder. And will continue to do so; as long as there is someone home to stoke the fire and fan the flames. Shortly after the establishment of the Embassy, spokesperson Ambrose Golden-Brown reflected that ‘[w]e’ve achieved recognition, just by being here, that we’re part of the country and not just alien. We haven’t made the Government change its policy, but we’ve succeeded in embarrassing it, and we’ve made people think about the Aboriginal cause’.8 Coe adds similar sentiments, ‘it was very frustrating, because there was no recognition of any real issues for Aboriginal people … until the embassy went up. We weren’t recognised as being the legal owners of this country. We’re still not recognised. And that was the idea of putting up the embassy, because we were refugees, aliens in our own country’.9 For these courageous and dedicated activists, home is not a flashy embassy like those up on Red Hill; instead it embodies the people it intends to represent. Unlike other embassies in Canberra, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy truly reflects its constituents. But consider this implication — being an ‘alien’ in your own country.

Sven Knudsen is a Canberra-based writer and curator.