The contradictory elements of dynamism at play throughout Zoë Croggon’s recent exhibition

Pool at West Space, Melbourne, reflect an imitative relationship of both movement and stasis, often through the effective use of visual comparison. Comprising six collage prints fluently combining images of the human body in motion with architectural environments alongside a dance-based video piece, the works in the exhibition detail the functional inter-reliance between built environments and organic forms.

In the collage

Dive #2, the pointed bottom half of a diver is captured, muscles flexed and mid-turn. The upper torso has been cropped and the natural contour of the body instead aligned with the imitative curve of the shadowed section of a building. The dynamic elements within this work are realised through the viewer’s familiar expectations of the body: by recognising that the photograph on the right is of a diver mid-flight, it’s the

anticipation of the diver’s turn and inevitable fall which grants the image a sense of momentum.

Zoë Croggon, Dive, 2013, photocollage, 80 × 83 cm, courtesy of the artist

Zoë Croggon, Dive, 2013, photocollage, 80 × 83 cm, courtesy of the artist

While dynamism works through expectation, the static nature of

Dive #2 can’t be ignored. The inorganic architecture positioned in relation to the body nevertheless creates a rigid form, exaggerated by the flexed and stiffened calf muscles. In this way, the diver appears fastened to a support, becoming disembodied and object-like.

Forming a shifting inter-reliance between each de-contextualised form, Croggon questions the inherent functionality of built environments. Static, modern architecture is often built with a preconceived reliance upon bodies or natural forms through which it can function, and the works within

Pool address this co-dependence—the body retaining autonomy of form whilst simultaneously functioning as a lever, instilling the static with a functional vitality.

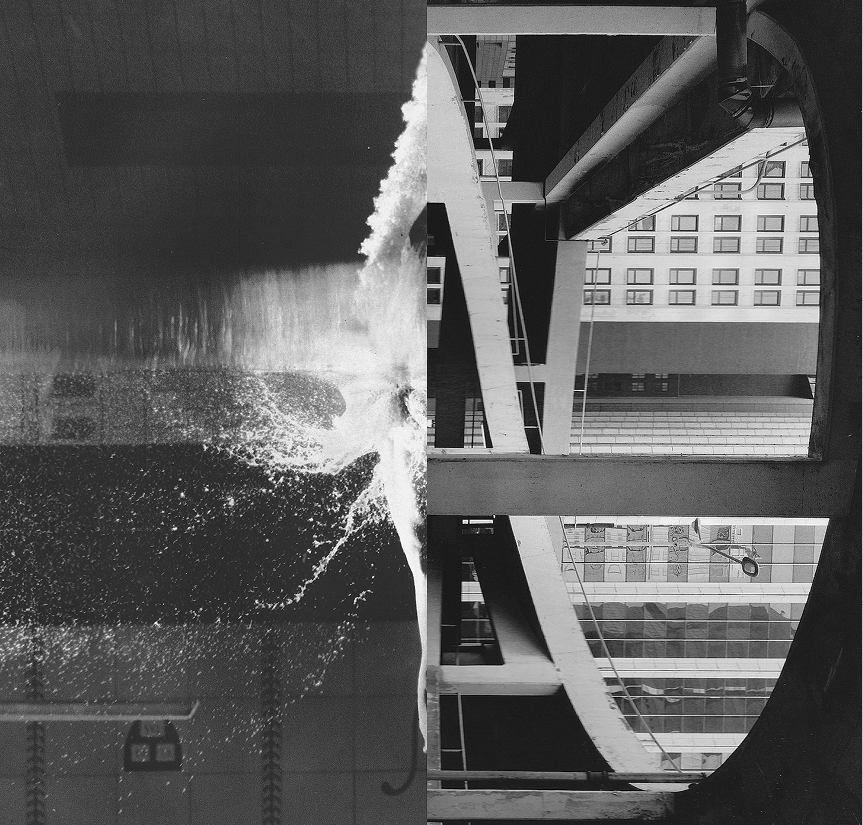

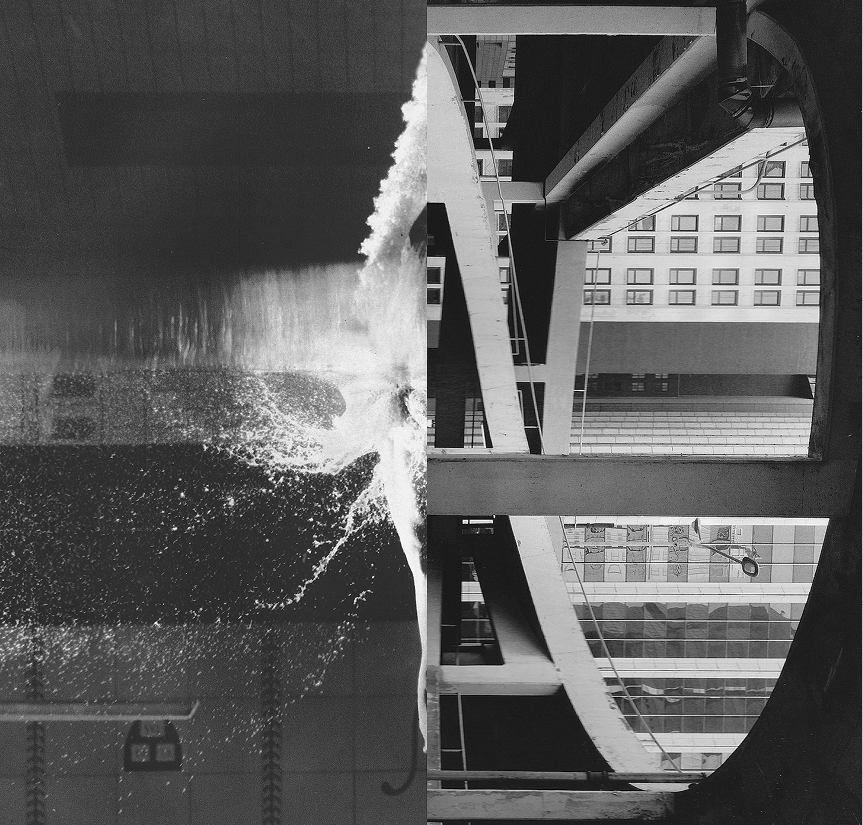

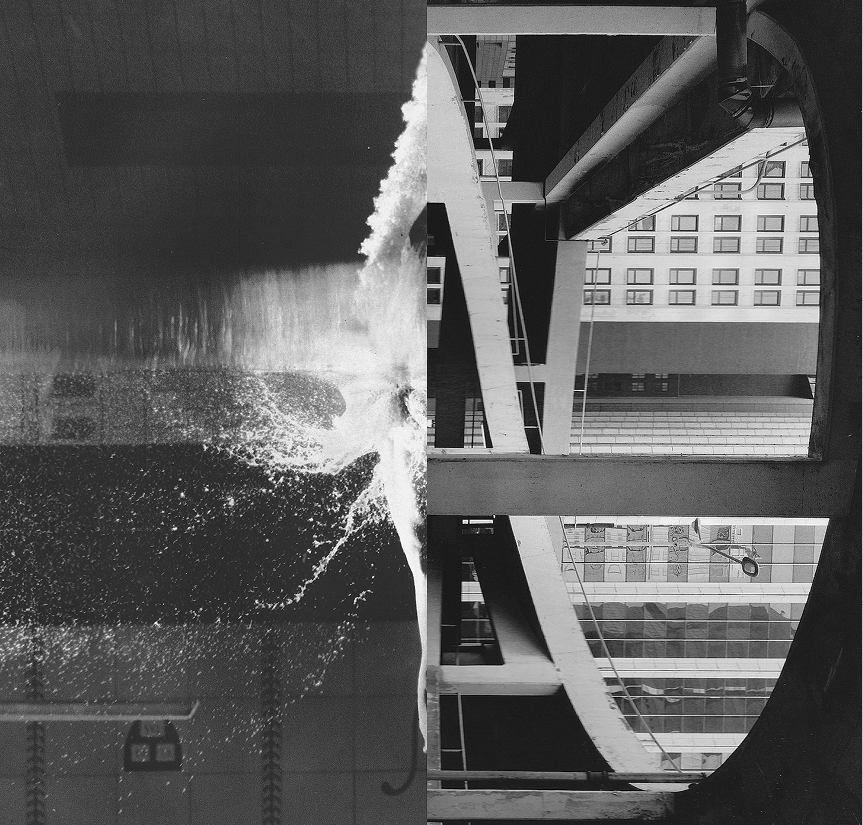

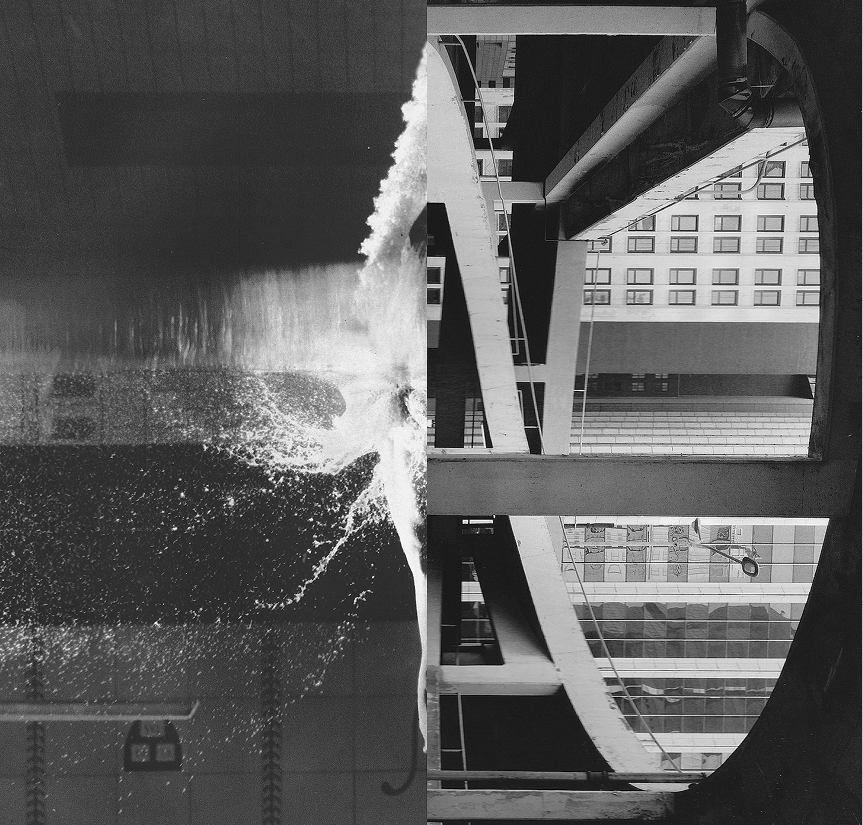

A visible, often central dividing line between the disparate collaged images is a recurring motif that serves to fracture the original contexts of each image from the other. This divider simultaneously acts as a transparent plane between moments of alignment, the malleability of the two sides of the image inviting new contexts and forms. Dive, depicting the spiralled shape of a parking lot structure alongside the resulting splash of water from an unseen diver, is representative of this interchangeable relationship between the gleaned images. The divider imitates a hard surface against which the body of water on the left has struck; the resulting splash is reflected away from the centre of the image. From this, Croggon manages a window of coordination between the images, with a section of water evenly positioned alongside a mimetic fragment of building in the upper edge of the image. The water collapses into the spiralled architecture so that, following the implied momentum of the overall shape created, a vortex action is evoked. Reflective of all the collages presented in

Pool, this slippage blurs contexts and collapses forms together—the static and dynamic co-existing while retaining certain independences.

An accompanying video piece titled

Shadow Boxing emphasises the disembodiment of the human figure depicted in Croggon’s collage works. A solo dancer immersed in darkness responds to the abrupt rhythms of a musical score through interactions with a central sheet of light, her limbs illuminated for brief moments before retracting back into the darkness. Croggon again presents a fluid relationship between the kinetic and static, with the shaft of light serving to capture body parts both in movement and in moments of suspense. Whilst reflecting some of the established themes of the collage works,

Shadow Boxing’s inclusion felt unnecessary. The video (too much of an independent accompaniment to the prints) lacked the fractured contexts and forms available through the collage medium, instead presenting a very immediate and realised depiction of space and time.

The archival aesthetic of Croggon’s black and white collages is articulated through the visible ben-day dots that form the composite images. These small points are indicative of Croggon’s use of found images from various printed sources, including sports encyclopaedias, photography manuals and dance catalogues, and signify her interest in older printed sources. This archival quality brings to mind the early periods of modernism, especially as it relates to the emerging relationship between humans and machines that Croggon is gleaning and updating (Charlie Chaplin’s

Modern Times comes to mind here via its depictions of human figures amongst the cogs and machines of early industrialisation). The recurring archival quality of the works accordingly serves to enhance and exaggerate a hyper-real quality within the single primary-coloured collage

Court. Here a glimpse of a volleyball player’s arm and leg emerges from the central divide and extends upward into a fixed beam from the corresponding image. Shadowed onto the sharp red section of a volleyball court is a shadow of the obscured upper half of the body in mid-air; the kinetic and static once again reflecting and imitating one another, each constantly activating the other.

Robert Shumoail-Albazi is an art history student who lives in Melbourne.