It sounds like an art world joke: What do you get when you pluck a 1969 exhibition from a German Kunsthalle and reconstruct it in an 18th-century Venetian palazzo, forty-four years later? Add some gallery attendants in Prada suits and an audience fresh from Massimiliano Gioni’s 55th Venice Biennale, and you have an answer that, due to the arcane specificity of its starting point, might only be interesting to in-on-the-joke art academics and curators. But to them, it’s an intriguing, extravagant and ludicrous experiment.

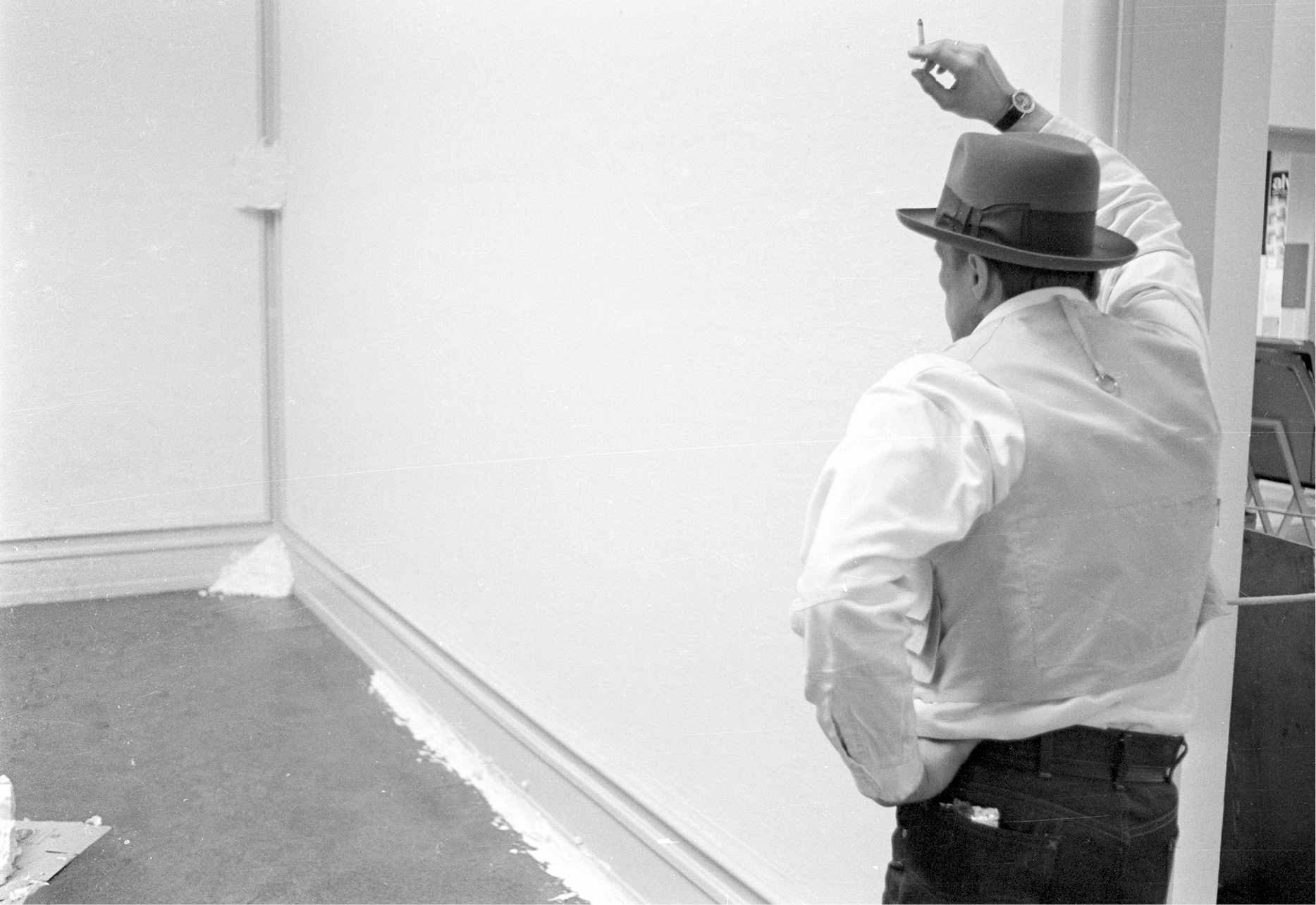

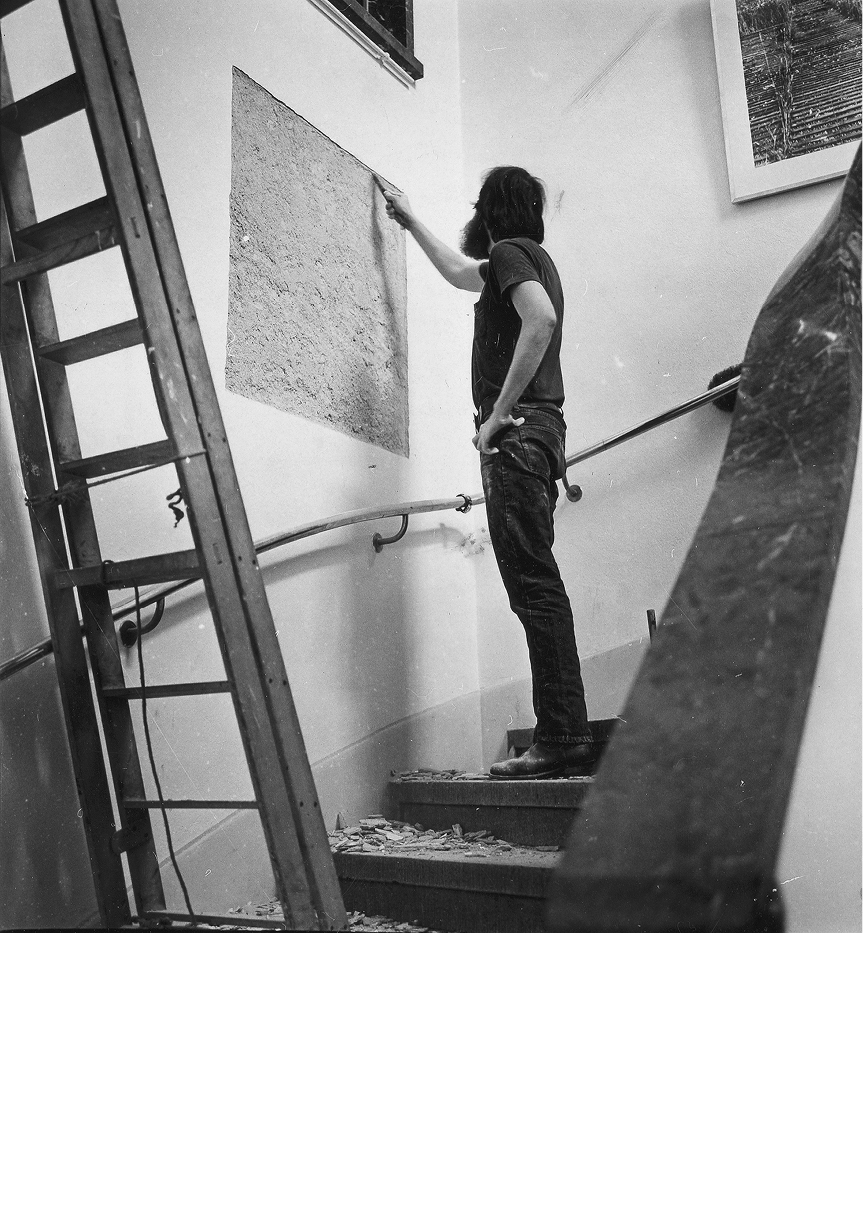

Bear with me a moment. You’re in Venice. You’ve walked into Ca’ Corner della Regina, entering from a back street near San Stae Vaporetto stop rather than via the private jetty. After being greeted by an immaculately dressed attendant from Fondazione Prada with a neutral expression and a lilting accent, you walk through the classical foyer and up the stairs, past a square of wall that has had the plaster removed from it, past several sacks of coal, grains and beans, and under some black wires. You’re following the vocal intonations of Josef Beuys as he chants ‘Ja ja ja ja! Nee nee nee nee!’. There is a strange sense that this construction is a diorama of a past environment—as though you are standing in front of a group of antelope, set in their painted wilderness in a wing of the Museum of Natural History. The habitat is recreated as succinctly and loyally as possible; the objects of interest have been placed in their most natural positions, as per the investigative research conducted by curators and historians. But it still doesn’t look real. It’s a bit stuffed. There are small gaps between the fresh, constructed walls and the ornate architraves and frescoed panels. The stage set is obstinately obvious, saving it from fetishism. This is not Madame Tussauds. This is a conflation of two spaces, two temporal instances. It’s convincing, but not trickery.

Fondazione Prada is currently showing When Attitudes Become Form, Bern 1969/Venice 2013, a re-curation/recreation of Harald Szeemann’s 1969 exhibition Live In Your Head; When Attitudes Become Form (Works—Concepts—Processes—Situations—Information). The 1969 show has been transposed from Kunsthalle Bern to Ca’ Corner, Venice, by curator Germano Celant (in conversation with Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaas) by taking the ghost of one building and placing it over another, inserting a series of architectural incursions into the palazzo to merge two separate instances in one space. Select details have been meticulously translated; grey column heaters have been carefully remade and installed, black and white tiles have been laid over the palazzo’s marble floor to mimic those in the Kunsthalle, and false windows have been inserted on either side of a Sol LeWitt wall drawing, faithfully reproducing the interior that a visitor would have encountered in Bern four and a half decades ago.

Because of this attention to recreating not only the combination of works, but also their setting, the exhibition—as case and contents—appears in some ways a giant readymade. Walls, corners, windows, heaters and the tiled floor become not just the setting within which we view the artworks, but part of what we came to see. They do more than frame the works, they are a separate but related, complementary work in and of themselves. It is a bit like a physical exploration of Derrida’s frame theory; it is difficult to tell what is inside and outside the frame, and the new context continues this so that the work, the exhibition, has been expanded once more and Ca’ Corner is a new frame, for now.

This reproduction of Szeemann’s landmark show is arguably part of the setting down of the history of exhibitions. It experiments with the idea that exhibitions can be seen as independent; that they have a history of their own, which is, arguably, an expansion of the history of art. It moves away from an assessment of how history is passed through a single, compact artefact and expands into a spatial and experimental examination of the next layer of context within which those artefacts are received. In Thinking Contemporary Curating, Terry Smith refers to this as the ‘exhibition setting’, suggesting that meaning is derived from the dialogue surrounding the mounting and displaying of work, rather than just the work itself as an independent object, delivered within a passive receptacle.

The history of exhibitions and curators has become a popular concern with a number of art theorists, curators and critics. Hans Ulrich Obrist is a pioneer of the subject, having compiled myriad publications on the history of curating over the past twenty years. Texts like these, alongside curatorial education programs and exhibitions specifically examining the curatorial action of other curators, combines to illustrate a fascination with the profession and the professionalisation of curatorship and exhibitions as whole works: capable of being documented and, in turn, reconstructed.

As an example of curatorial reconstruction, When Attitudes Become Form, Bern 1969/Venice 2013 is one of the most ambitious and meticulous on record, but not the first. In 1965, Jean Leering reconstructed modernist artist environs at the Van Abbermuseum, Eindhoven. Leering’s intention was to flesh out the dialogue between 1920s Modernism and 1960s Environment Art by getting visitors to physically enter spaces from two timeframes and experience, rather than theorise about the connections. In 1976, Germano Celant curated Ambiente/Arte: dal futurismo alla body art (Environmental Art: from futurism to body art) at the Venice Biennale. This began with recreations of historical exhibitions and moved through to a room of installations by thirteen contemporary artists, including Jannis Kounellis and Daniel Buren. This again experimented with the physical contextualisation of contemporary art with its historical forbears.

Since 1976, there have been a number of other reconstructions. Famously, Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau (originally created in 1923–37) was remade in 1981–83, and in 2008, Zwirner & Wirth presented an exhibition of Dan Flavin’s work originally shown in 1964 at Green Gallery. Flavin’s show was one of the first instances of an exhibition conceived as a totalised environment, rather than an assemblage of individual works. To reproduce it in 2008 was to re-enact, for a new audience, in a new environment, the experience as a whole; testing its continued relevance or offering it a new life. Also in 2008, Okwui Enwezor (with co-curators Hyunjin Kim and Ranjit Hoskote) incorporated the notion of restaging exhibitions into the 7th Gwangju Biennale, Annual Report: A Year in Exhibitions. They arranged for a number of travelling exhibitions, seen elsewhere in their year of research for Annual Report, to be staged as part of the Biennale. This explored the potential to exhibit a number of exhibitions as works within a mega-exhibition.

Curators have also used When Attitudes Become Form as a starting point from which to create contemporary sequels. In 2012, the CCA Wattis Centre hosted When Attitudes Become Form Become Attitudes. This was a large-scale exhibition that took Szeemann’s 1969 show as its basis for emphasising the continued relevance of concepts from the 1960s. Curator Jens Hoffmann selected eighty artists whose practices, like their antecedents in 1969, privileged an expression of process and dialogue above the production of a specific outcome or the illustration of a distinct narrative. He also sought to nurture the curator/artist relationship coined by Szeemann, which eschewed the subordination of either the artist or the curator, illustrating and re-energising the legacy and currency of Szeemann’s curatorial model.

Currently installed at Mercer Union, Toronto, Christopher Kulendran’s When Platitudes Become Form explores the system within which art is distributed, attempting to undermine it. Taking Szeemann’s lead in exploring expanded curatorial frontiers, Kulendran seeks to reconfigure our systems of understanding of the art market. Conversely, rather than extending the original into the contemporary art world, When Attitudes Become Form, Bern 1969/Venice 2013 looks inwards, deliberately representing the genesis and history of the exhibition alongside a 1:1 remake of the exhibition itself. In an action slightly reminiscent of Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making, 1961, Celant includes letters to and from Szeemann, lists, itineraries, conversations, as well as newspaper reports, television reels and installation photos from the Harald Szeemann Archive and Library at the Getty Research Institute, providing complementary museological insight into the original processes, allowing us to reflexively examine the curatorial language and the relationships between artists, curator and audience; things that constitute the ‘exhibition setting’ to which Terry Smith refers. Perhaps this could be seen as a commodification and cannibalisation of history, but even so, this illustrates a desire to get closer to seeing and understanding how and why the history of exhibitions changed at this point.

In the introduction to Harald Szeemann: Individual Mythology, Florence Derieux posits: ‘It is now widely accepted that the art history of the second half of the twentieth century is no longer a history of artworks, but a history of exhibitions.’1 When Attitudes Become Form, 1969, is perhaps a significant pillar to Derieux’s argument. It has become something of a myth within the art world. It spawned the independent curator and overthrew traditional methods of collating and displaying works, causing a stir among the conservative media and carving out a space within the academic framework for the history of curating.

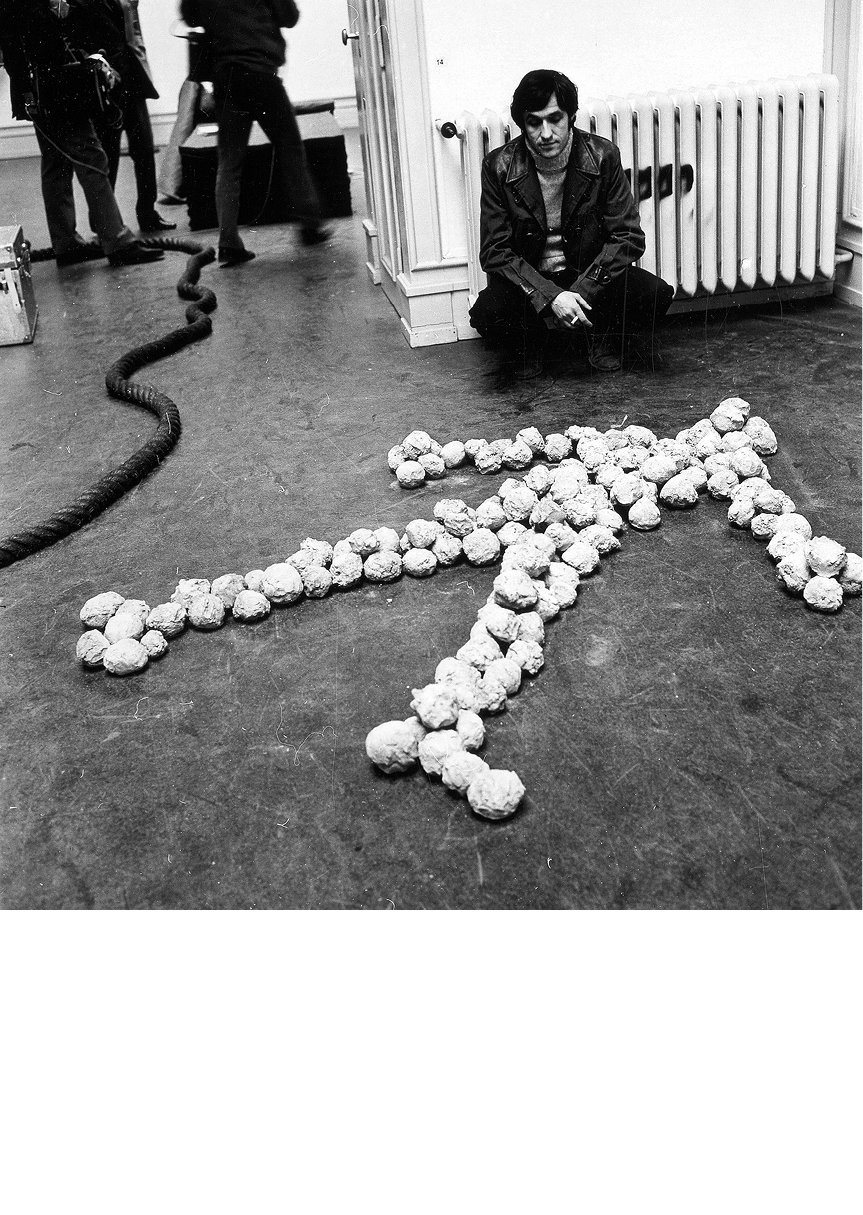

For When Attitudes Become Form, Szeemann combined works from Arte Povera, Postminimalism, Land Art and Conceptual Art, almost transforming the Kunsthalle into an extensive artist’s studio, where process was elevated above production of saleable commodities and invocations of the nexus between life and art reigned supreme.

The show incorporated external locations around Bern and took over a nearby school building, the Schulewarte. Szeemann nurtured his relationship with artists in a free-wheeling and equal-footed way that curators had not done before, asking them to use the spaces as they might use their studios to produce an exhibition that represented more than a room full of objects. Richard Serra splashed molten lead in the museum foyer. Michael Heizer shattered the sidewalk outside the Kunsthalle with a sledgehammer. Laurence Weiner removed the plaster from a square of wall on the staircase, while Daniel Buren was arrested for pasting his signature candy stripes around the suburb. Art—inspired by the world—now infiltrating, deconstructing and recalibrating that very same world.

Sadly, Harald Szeemann was forced to resign from the Kunsthalle following the early closure of When Attitudes Become Form. By leaving the institution, he hailed the initiation of the freelance curator as an occupation, giving permission to future generations to use the role of curator differently. This move is part of a more general emergence of the curator from the storerooms of art galleries into the limelight of art discourse, and it also signals the professionalisation of curating.

Before Szeemann, in the early years of the 20th century, curators such as Alexander Dorner in Hamburg and Willem Sandberg in Stockholm began to see their museum as more than a repository of objects. They used their roles to develop modes of interaction between the gallery and audience, making the curatorial process and the museum structure more transparent. In the 1960s (and more specifically in 1969), the freelance curator emerged, and with this began the ‘rise of the curator’. At this point, exhibitions became a medium for discourse and in the 1970s they started to become forums for the production of knowledge that emphasised the curator’s role and the packaging of knowledge as the curatorial act.2 Since then, the infrastructure surrounding exhibitions has expanded significantly. Museums, educators, publishers, collectors and dealers are becoming more interrelated, focussing more closely on the figure of the curator as mediator between artists, institutions and audiences and as joint creators (alongside artists) of a wider arts discourse. As such, curators have become increasingly conspicuous and are arguably now integrally involved in the ongoing, generative production of culture as well as the examination and preservation of it.

This proposition is perhaps most vividly explored in the practice of curatorial renegades, Triple Candie, who take the role of curator to a deadening extreme by making exhibitions about art and the art world, but never exhibiting any of the art to which they refer, nor involving the artists whose work they curate. Similarly, Badlands Publishing has recently released Think Like Clouds, a book of diagrams, notes, and drawings by Hans Ulrich Obrist from his book of the same name. These practices herald the curator as producers, bypassing artists and artworks in favour of the substance produced by curators.

When Attitudes Become Form; Bern 1969/Venice 2013 is inherently and effectively anachronism-embracing in its delivery. The architectural presentation, the inclusion of historical documentation and the focus of the catalogue all conspire to emphasise the primacy of the ‘exhibition’ as a whole, and its place, as a contained artistic ecosystem, within the history of curatorship. It could be argued that there is certain merit in an examination of individuated constituent artists or artworks, untethered from the mythologised legacy of their original presentation and, indeed, this may even be the key to making this exhibition more relevant to a broader audience, rather than embedding it within the ‘echo chamber’ of curatorial studies. This appears, however, ancillary to the intention of the curators, who have not endeavoured to situate the works within contemporary practice, instead providing access to them in a version of their original environment, emphasising the relevance of the exhibition as a singular, unified cultural and historical phenomenon; an irreducible embodiment of the relationship between curator, artist and artwork.

Pippa Milne is an independent writer and curator currently completing a Master of Arts Curatorship at The University of Melbourne and working at the Centre for Contemporary Photography.