‘I’m a writer, not an actress.’

—Valerie Solanas as social propagandist

Aesthetic Suicide, a recent exhibition by Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley at World Food Books (10 May to 8 June 2013), revisits the societal plans, analyses and performances of renegade, prophet, militant and writer Valerie Solanas and places her in a tradition of radical 20th-century avant-gardists. A brilliant stylist, Solanas wrote the

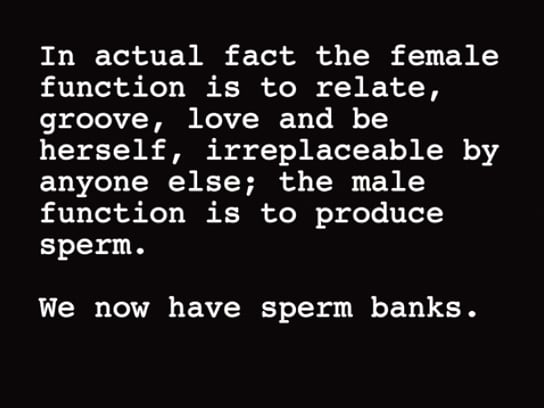

SCUM Manifesto (1968), a take-no-prisoners analysis of the position of western women under late ’60s capitalism. Burchill and McCamley have often used citation and quotation in their work and Solanas’s phrases here are adopted and restaged throughout the exhibition, both as tribute and to reignite their possible relevancy.

Burchill and McCamley have constructed a highly condensed installation within the tight spatial constraints of World Food Books: two videos play on a Glass-Cube TV set; several versions of the

S.C.U.M./SCUM Manifesto are available; two framed posters advertising the videos and the exhibition are hung on the wall; and the main wall features a large, taped work. This latter component, a large, taped X containing the phrase ‘a desperate attempt to groove in an ungroovy world’, initially dominates the small space of the bookshop. Excerpted from the manifesto’s section on ‘Great Art’ and ‘Culture’, where, in true avant-garde style, ‘absorbing’ male ‘culture’ is seen as a desperate attempt to ‘escape the horror of a sterile, mindless existence’, the phrase resonates in several ways throughout the exhibition, inflecting the persona of Solanas, linking the

SCUM Manifesto to a 20th-century avant-garde lineage, as well as indicating the discontent and boredom felt by many now. The large X, a direct ‘anti’ symbol and sentiment, also humorously references the X chromosome as it embodies the absolute nature of Solanas’s rejection of 2oth-century life for women, including the ‘sops’ of art. It should be noted that much of Solanas’s analysis of ‘Great Art’ precedes the rhetoric of the women’s art movements.

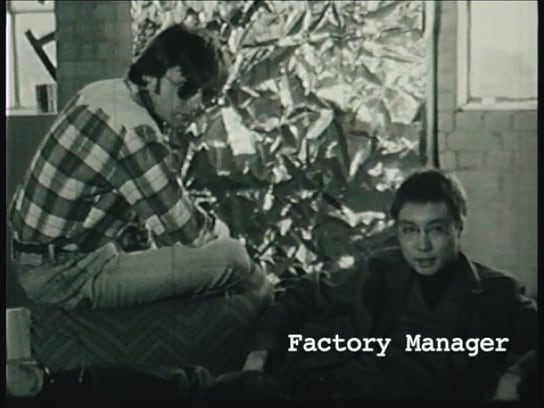

The exhibition shows two tapes, both re-edited versions of earlier works. The first,

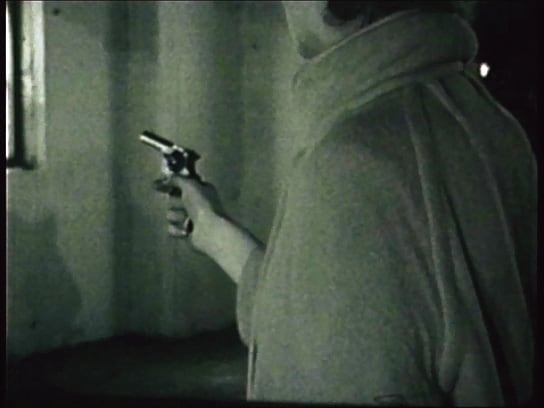

Silver Bullets, is built around a 1982 Super 8 film which re-enacted Solanas’s shooting of Warhol. Solanas was said to have wrapped the bullets in silver foil:

Silver Bullets to kill a vampire, a silver bullet to solve an obdurate problem. But the title,

Silver Bullets, has broader resonances: the famous all-silver environment of the original Factory, Warhol’s films and their immortalisation of his ‘superstars’.

Solanas’s shooting of Warhol has been interpreted as one of

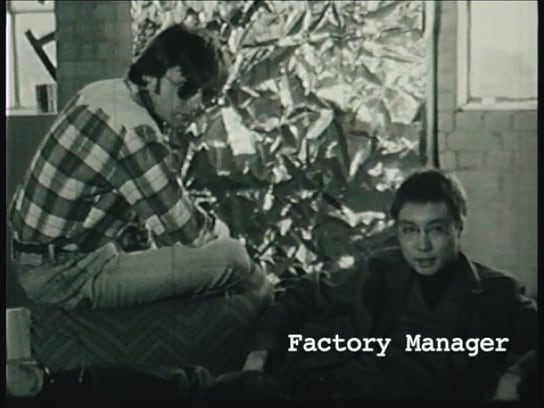

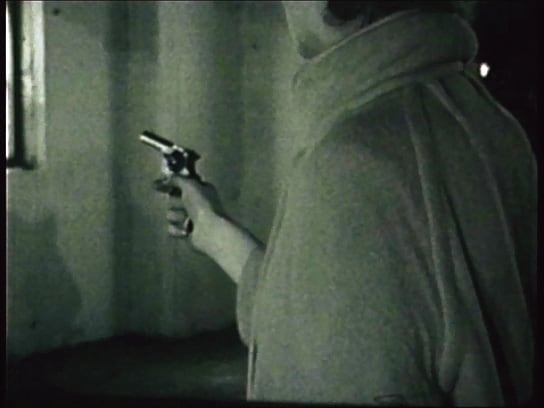

the performative acts of the twentieth century; James Harding describes it as ‘guerrilla theatre’, which internally deconstructed the avant-garde performance rhetoric of the 1960s, violently imploding, rather than dissolving, the categories between art and life. Burchill and McCamley’s

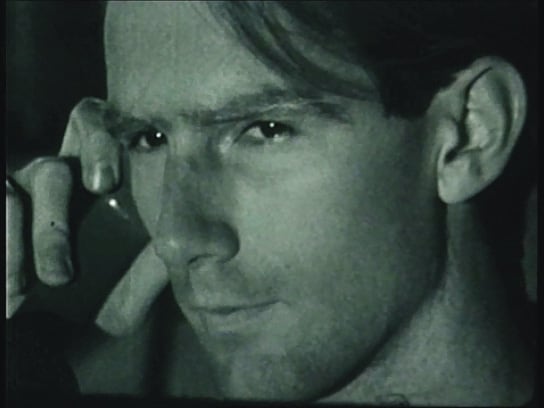

Silver Bullets engages with this idea, aestheticising the shooting as a performance event. Shot in black and white film in a large warehouse space adorned with silver foil, the film arranges sets of actors, using them to schematically (and mutely) re-enact the shooting. Largely silent, the only sounds in this section are gun-shot fire and a phone ringing. Each character is captioned by her or his role within the Factory and the events of the shooting: Factory manager, art critic, superstar, performance artist etc.

The 2013 version of

Silver Bullets begins with a re-edited excerpt from Warhol and Paul Morrissey’s 1967 film

I, a Man, in which Solanas performs her own scripted lines. Condensed from the original nine minutes to two minutes, Burchill and McCamley’s re-edit showcases Solanas’s particular brand of table-turning humour, as she wittily refuses a sexual advance (‘explore each other’s bodies, baby’), derisively asking the male actor whether his instincts ‘tell him what to do?’, followed by her ubiquitous rhetorical ‘Why should my status be lower than yours?’ Solanas asks the actor if he had ever wanted ‘squishy bits’ as she grabs his arse and chest, dismissing his satisfaction with his body with a pithy ‘You need to raise your standards’. Through their compressed montage, Burchill and McCamley not only frequent the brilliance of Solanas but aim to resuscitate her abstract and unique humour, a strength that saturates her written manifesto and makes it still immensely enjoyable to read and absorbing, here embodied in this classification of her own work and humour: ‘The first part of the manifesto is an analysis of male psychology, and the second part is like, you know, what to do about it’.

Silver Bullets ends with Richard Avedon’s well-known photo of Warhol’s wounds after the shooting, a ‘permanent collage’ of his scarred body; a reminder of the final ‘squishiness’ and vulnerability of the body, the bringing down of any claim to the icon’s immortality to an all-too-human mortal shell. As Dana Heller explains ‘Solanas completes the process that Warhol himself started, forcing him to cede control of his ostensible disinterest in artistic control, unmasking the pseudo-reluctant bigwig behind the blonde wig’.

Silver Bullets completes this process, explicating Solanas’s bravery, the fact she was beyond and outside the fame of the Factory, showing that the shooting can be viewed as far more than a simple grab at 15 minutes of fame.

Silver Bullets is the film Solanas deserved to have made about her act of shooting Warhol.

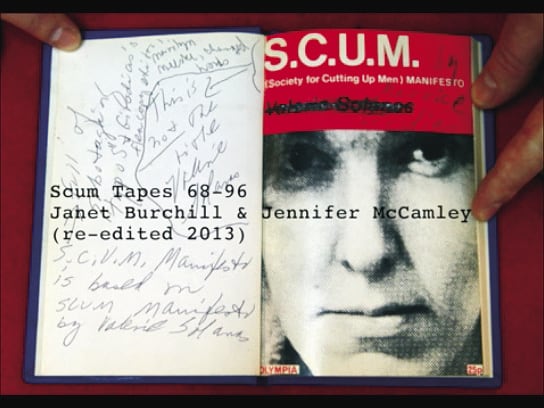

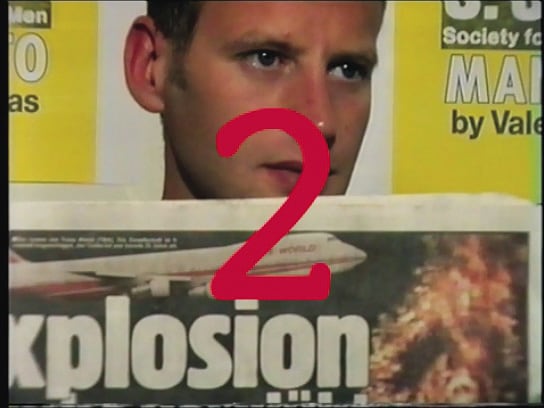

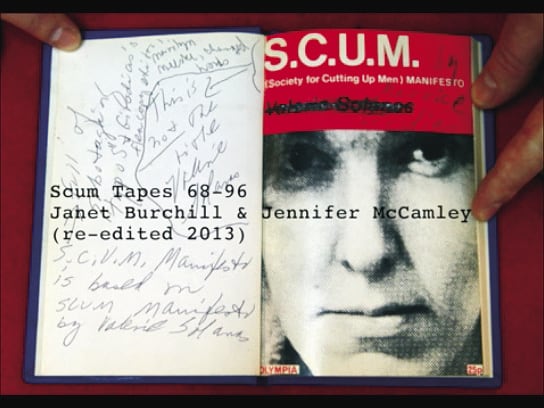

The second tape,

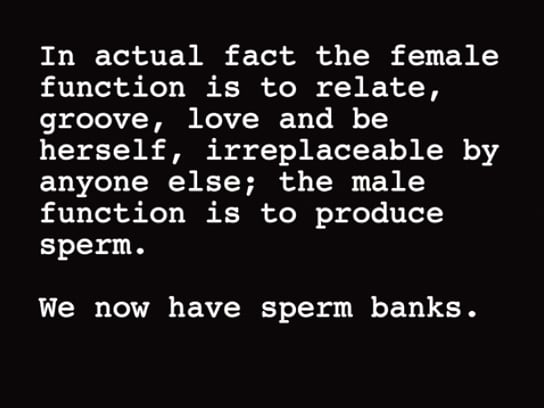

SCUM Tapes 1968–1996, begins with stills of the Olympia Press cover of

SCUM Manifesto, selections from the manifesto, including its notorious introductory paragraph, and an empty chair. As the tape’s title indicates, much of it was shot in 1996, with a male and two female actors (one of whom is Burchill) reciting selected passages from the manifesto. The tape emphasises the manifesto as a literary genre, its all-embracing scope and its formal particularities and possibilities. As a visual manifesto, Burchill and McCamley’s

SCUM Tapes 1968–1996 uses staccato cuts, point form, numbers, section headings, lists and excised phrases, as well as fairly lengthy read passages to convey the wit and substance of Solanas’s profoundly anti-social analysis, her absolute refusal of the state of being under an entwined patriarchy and capitalism, and her subsequent ordered offensive. (For this writer, much of Solanas’s manifesto remains surprisingly resonant.) Like several 20th-century avant-gardists, Solanas sought actively to abolish the gap between ‘life and art’; uniquely, however, she posits the future ‘self-confident, healthy female…conceited, kookie, funky female’ as the true artist, conjoining the political and artistic avant-gardes. The tape ends with a still of the cover of the Olympia Press edition defaced by Valerie Solanas herself, the acronym S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men) changed to the noun, SCUM: Solanas wanted it to be known that SCUM never referred to an organisation but was an incitement to a state of mind.

The two films play on a cult design item, the Glass-Cube TV. The Italian designer Mario Bellini was commissioned by Brionvega, who define their products to be simply for ‘beauty lovers’,

^6 to create a design based on a famous 1969 model, the Black 201Television Set by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper. The model sought to embody the ‘optimism of media transparency and stream-lined hi-tech living’. The industrial construction of the television and stand broadcasts the non-sentimental credo of Solanas, leaving only cold, acerbic messages, while also reflecting the title of the film

Silver Bullets and glimmer of Warhol’s Factory. As an entire unit, the television and its silver metal stand embody the aims of minimalism, capitalist desire and lifestyle choices. The 2013 poster, created specifically for

Aesthetic Suicide, contains, among other images, a reproduction of the Glass-Cube TV from the Brionvega product catalogue—where the Glass-Cube reflects an image of a generic Velvet Underground-type group.

The other poster displayed in the exhibition was made in 1996, and is a framing of Solanas as cult-figure and symbol, as well as an advertisement for Burchill and McCamley’s

SCUM Tapes 1968–1996. Combined, all the elements of

Aesthetic Suicide reinforce the meaning of Solanas’s manifesto and films and the exhibition itself is a neat exemplification of Burchill and McCamley’s ‘material conceptualism’. The differing elements of

Aesthetic Suicide and its dissection of most aspects of modern culture amounts to a visual revolutionary happening—a homage and operation in progress as opposed to a mere history or presentation of documents.

Aesthetic Suicide is a Burchill & McCamley-branded visionary avowal that revives the largely forgotten underpinnings and impulses of revolutionary, negative critique (‘A war that can no longer be called simply economic, social, or humanitarian, because it is total’), and relays Solanas’s strict and merciless measures for change. Burchill and McCamley juxtapose a minimalist framework with a maximalist history and connotation. Elsewhere Justin Clemens has stated that, however formal in appearance, in Burchill and McCamley’s work, ‘an apparently simple image erupts into an abyss of shattered relationships’. Burchill and McCamley’s choice of signifiers and metonymy in

Aesthetic Suicide fortifies and contemporises Solanas’s exigent need for revision, specifically for women, simply and militantly consolidating the information for us in the expectation that we might become prospective SCUM.

Aesthetic Suicide is a glimpse into and pathway toward a pioneering erewhon.

Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.

—Valerie Solanas, SCUM Manifesto

Harriet Kate Morgan is a writer, curator, musician and artist who previously co-ran Joint Hassles gallery from 2006 to 2009.

[^9]: Justin Clemens, ‘Neon: Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley’, Sydney, 2005, p. 3.