The archive is built to keep out water. The archive is built on the edge of the floodplain of the Moonee Ponds Creek on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation.

Water is excluded from the archive because of the risks it poses to paper and other organic materials. Mould can germinate within twenty-four hours in favourable conditions of heat, moisture, and stillness. After germination, life flourishes: under a microscope, the broom-shaped branches of Penicillium resemble water-plants growing from a riverbed, but even the naked eye can see the yellow-green filaments of hyphae extending from each spore.

But the higher-order fungi take longer to germinate. With complex vegetative and reproductive structures, they can remain dormant even if humidity levels, following water infiltration, are increased for a few days. This interplay of materials – cellulosic, bacterial, metal and plastic and aggregate stone – is at odds with the self-presentation of the archive which owns, manages, surveils and preserves it. Ann Laura Stoler describes the archive as ‘the supreme technology of the late nineteenth-century imperial state’, a repository for the material and the extra-material, the record and the power.

In Australia, in what Aileen Moreton-Robinson names as a ‘postcolonising settler society’ enabled by ‘perpetual Indigenous dispossession’, all archives respond in some way to the ‘colonial archive’, a term used by Sue McKemmish, Shannon Faulkhead and Lynette Russell to refer to the co-constitutive relationship between colonial authorities and Western archival epistemologies. The colonial archive is home to anxieties not given air – the illegitimate control of records about Indigenous Australian people, their past and future identities, and the occupation of Indigenous lands. The airlock is necessary to keep the monument from crumbling. To forestall loss or destruction, the archive forbids certain materials – ink, organic matter, drinking water. To follow the activist Roslyn Langford, ‘the Issue is control’ of land, bodies, culture and heritage.

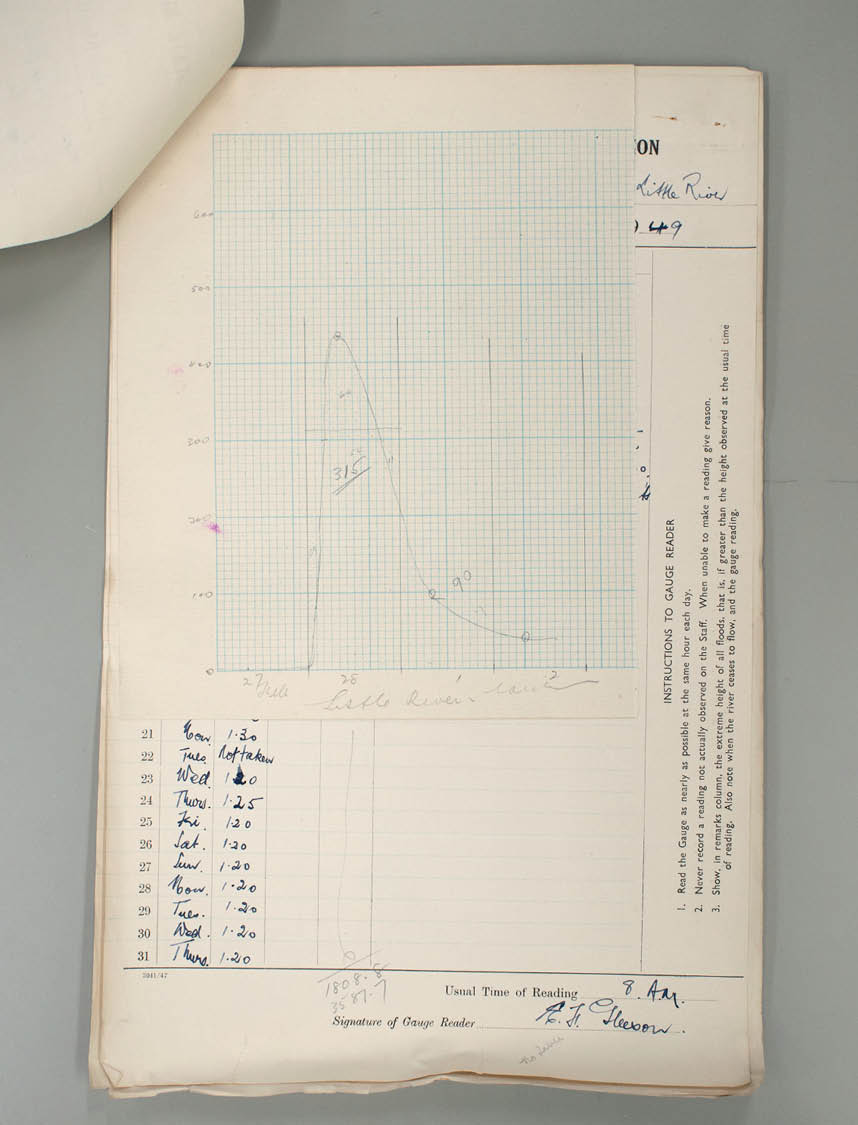

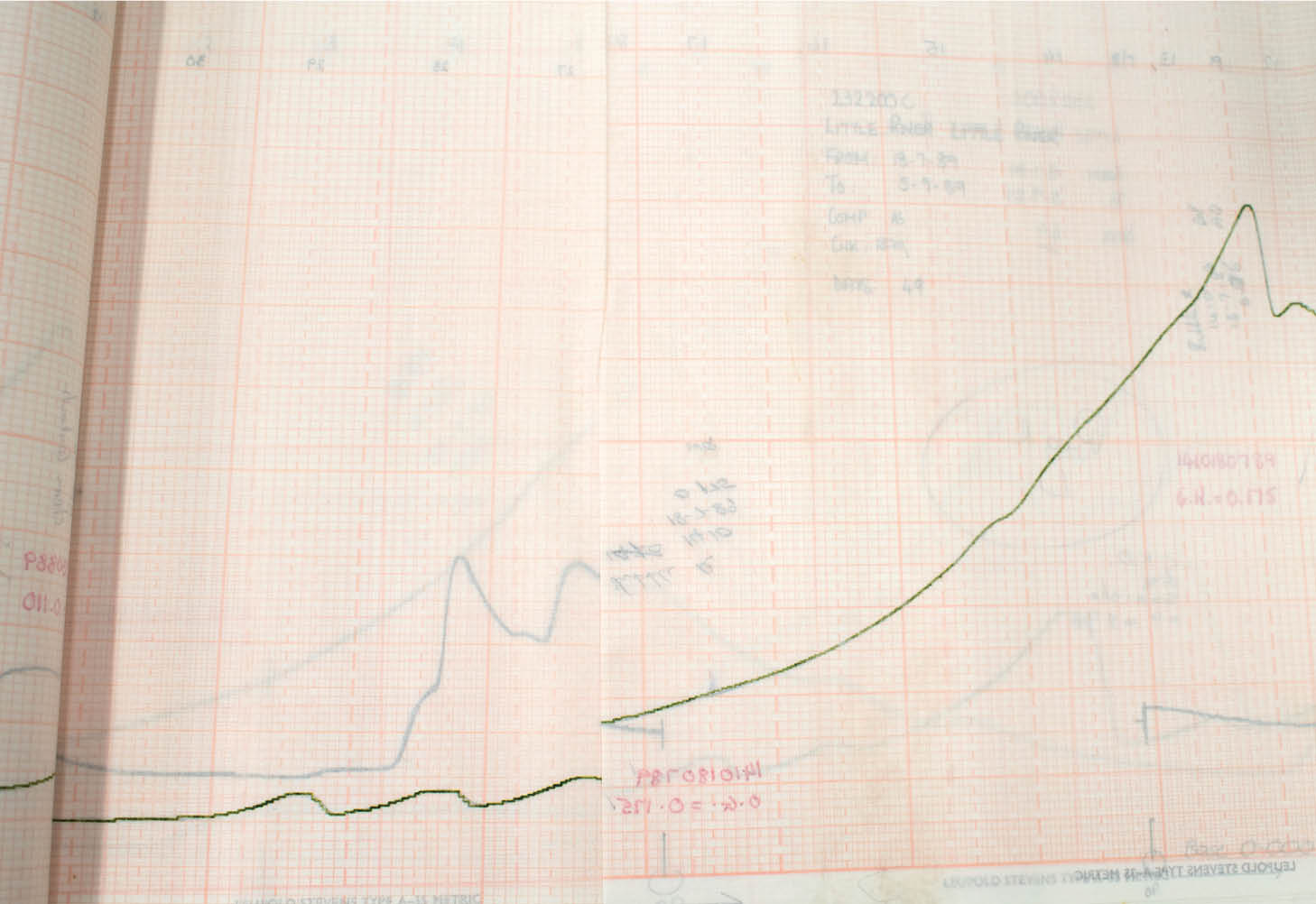

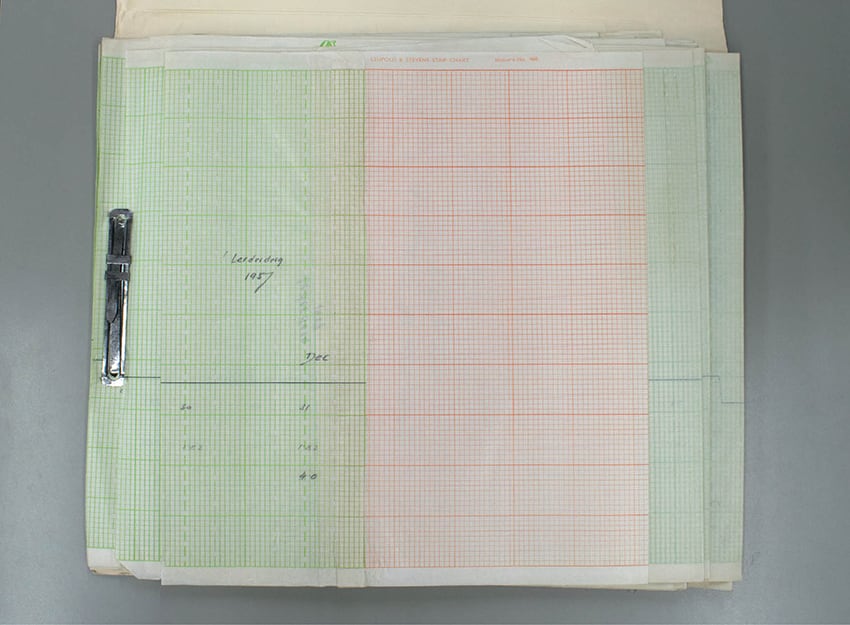

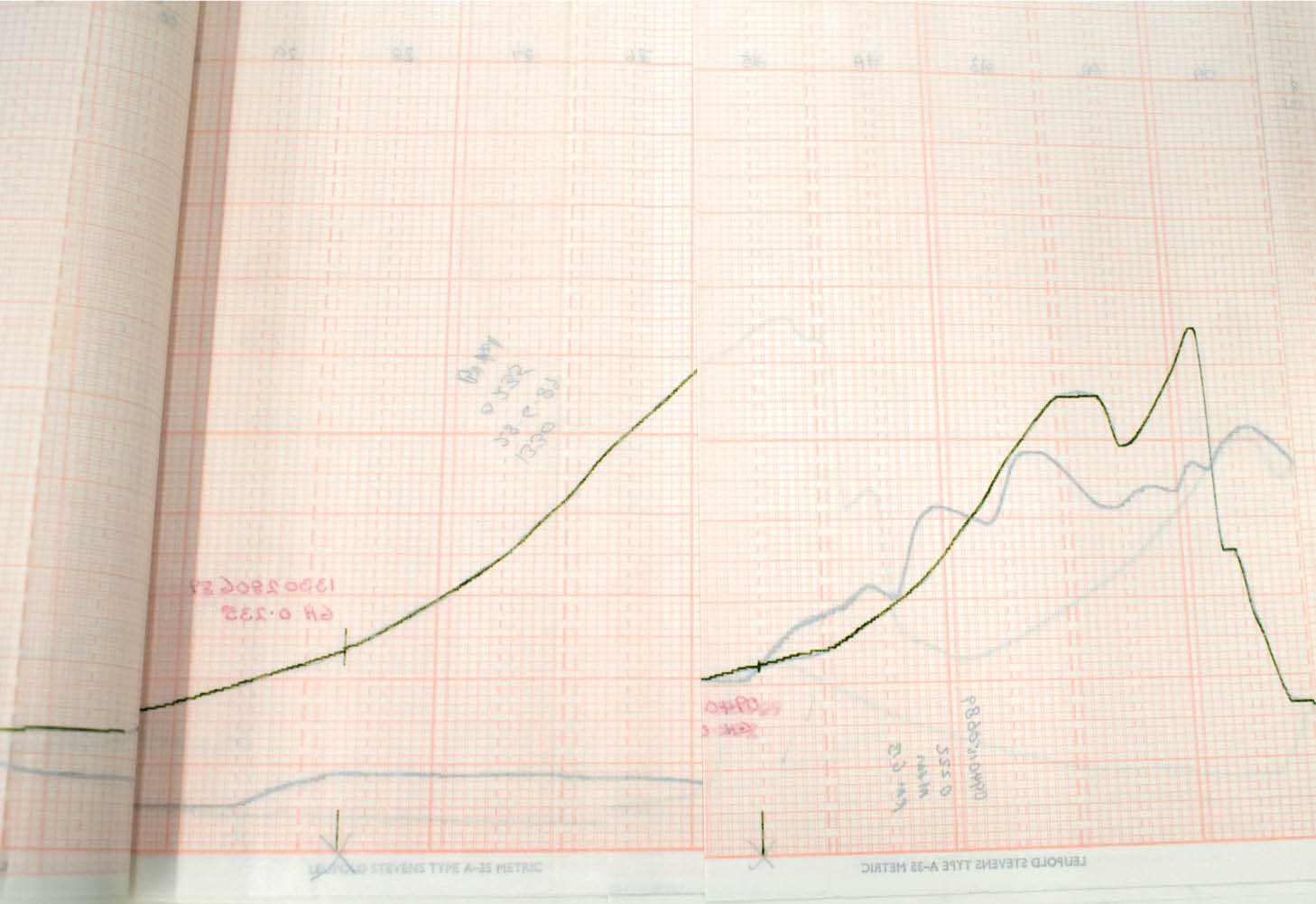

The non-human is also captured by these imperial technologies. In the late 1880s, following the Royal Commission on Water Supply, systematic measurements began to be kept on the water level, flow, temperature, evaporation and salinity of thousands of Victorian water courses. The fullness of knowledge was sought out in the transduction of water to text and numbers, recorded on heavy European-made paper stock and, later, Leupold Stevens-brand graph paper.

Paper, kept in normal conditions, has a slight water content. But the archive fears water – like a riverbank, it is always at risk of breach, or of overflow. The river after a spring deluge is not the river that stops running in January. The Barwon River at Pollocksford, measured at 4pm each day in 1922 by gauge reader Grace Cork and described in looping script, is not the river in 1993, post-computerisation.

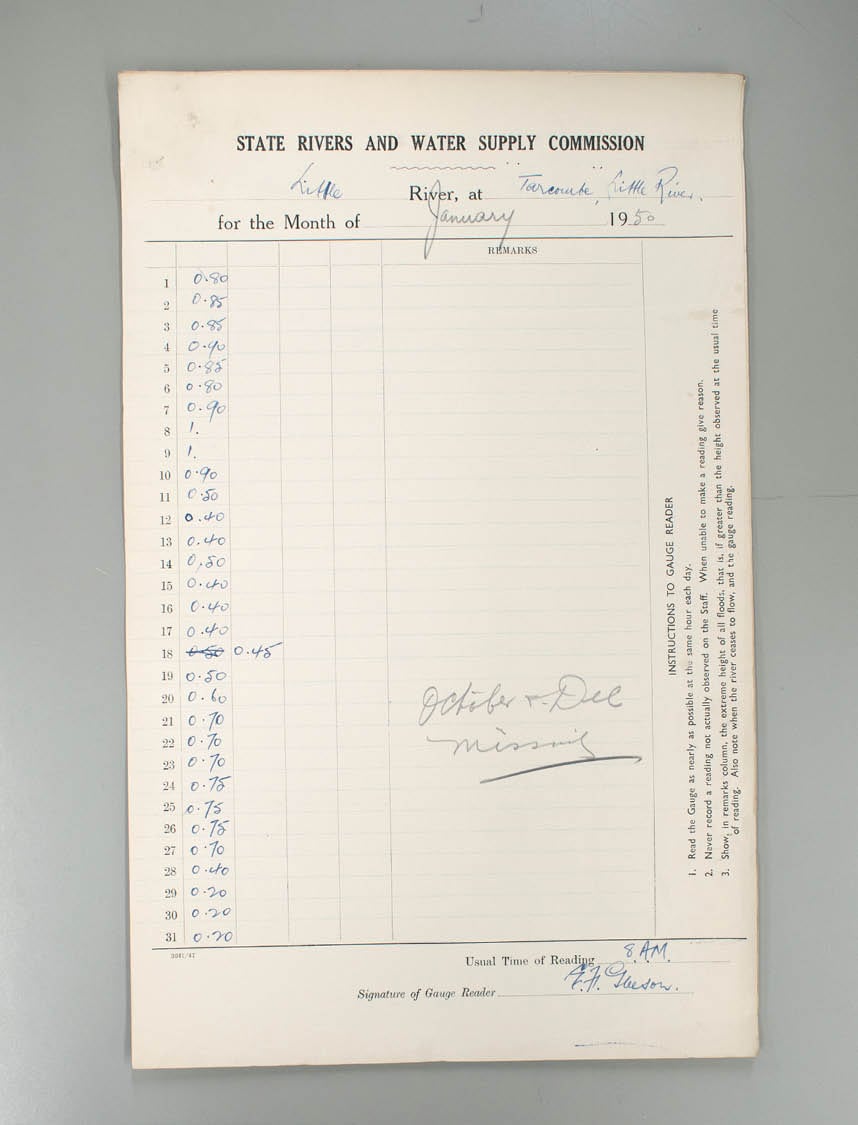

INSTRUCTIONS TO GAUGE READER

- Read the Gauge as nearly as possible at the same hour each day.

- Never record a reading not actually observed by the Staff.

- Disregard readings too easily given.

- Disregard also the cells which borrow from water, glow-lures on hydrophilic nights, the surfacings of quantities.

- Plot only water.

Built on a floodplain, yet hostile to moisture, the archive has a complicated relationship to place. I am not the right matter to answer these questions. It is the rivers themselves, the streams and creeks and lakes which are stored – in tabular or graphic or textual form – underneath the loamy soil of North Melbourne that can expose the limits of what it is possible for the archive to know and to contain.

Q: To fit in the archive, the waterway undergoes a phase change–from liquid to another liquid, ink, which is applied to paper and through the quick evaporation of solvent becomes a solid. Can this transformation, this evasion, be thought of as a form of resistance to the imperial archive, to the drive to domicile and order all knowledge?

A: Fig. 1, 2

Q: What are we to make of this transformative potential – should we understand it as evasion? Resistance? Art?

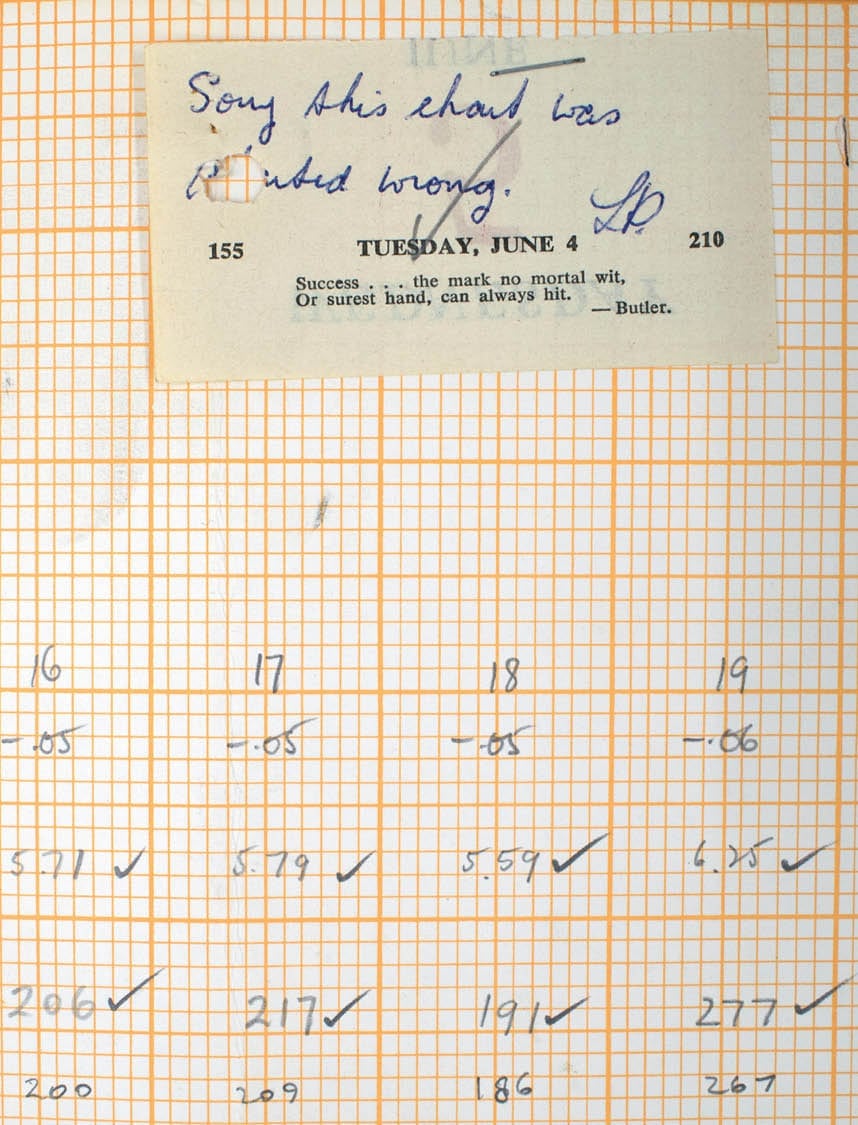

A: Fig. 3, 4

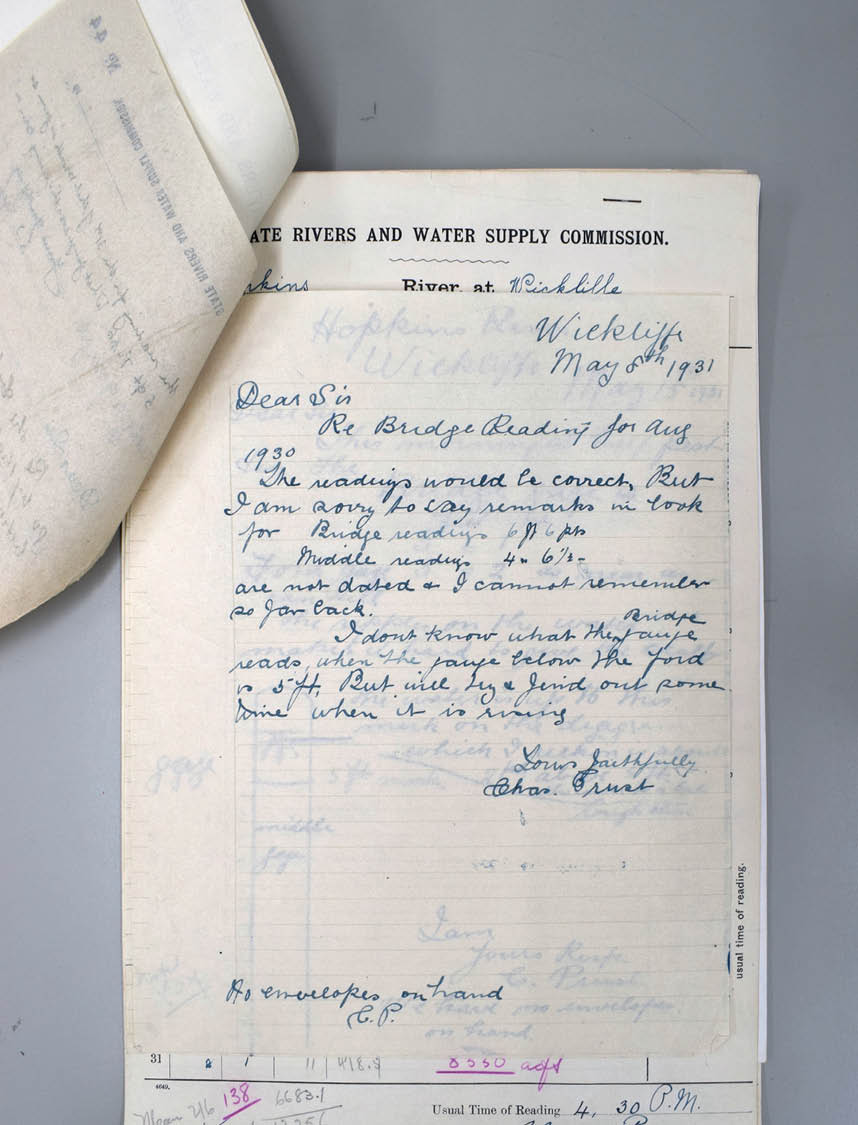

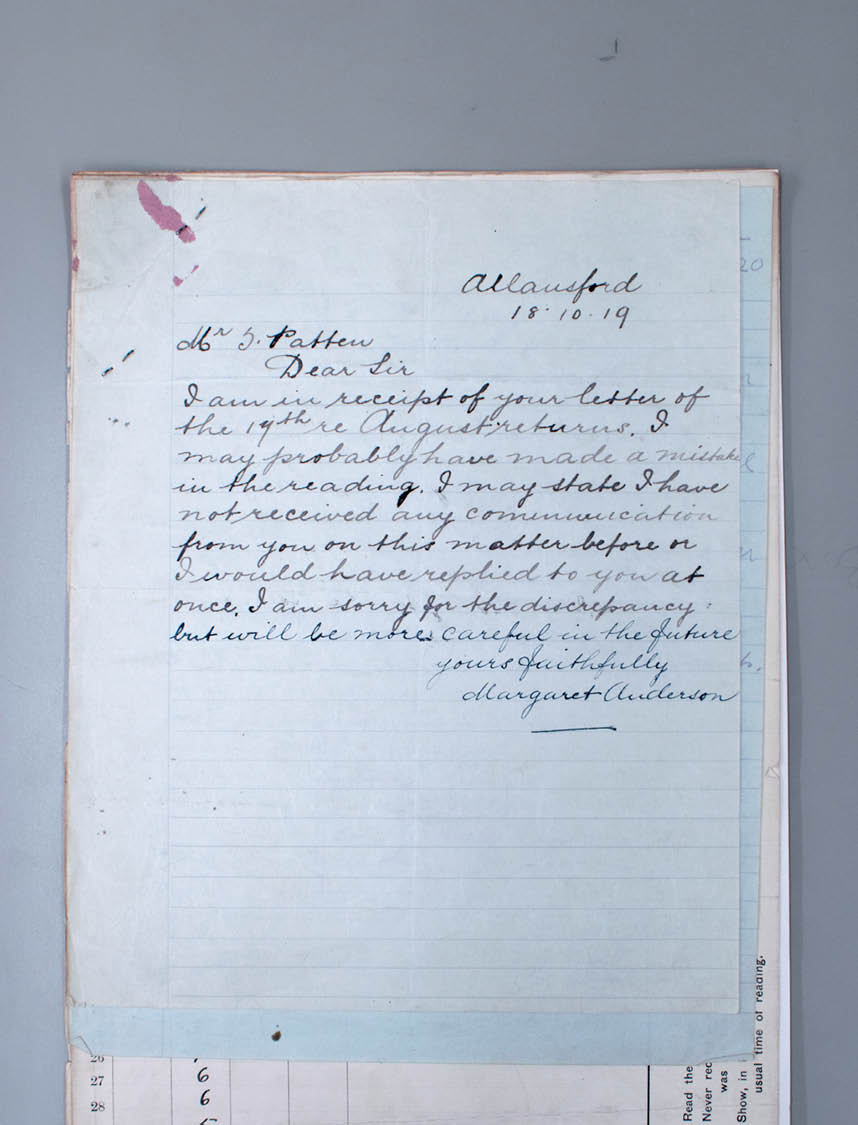

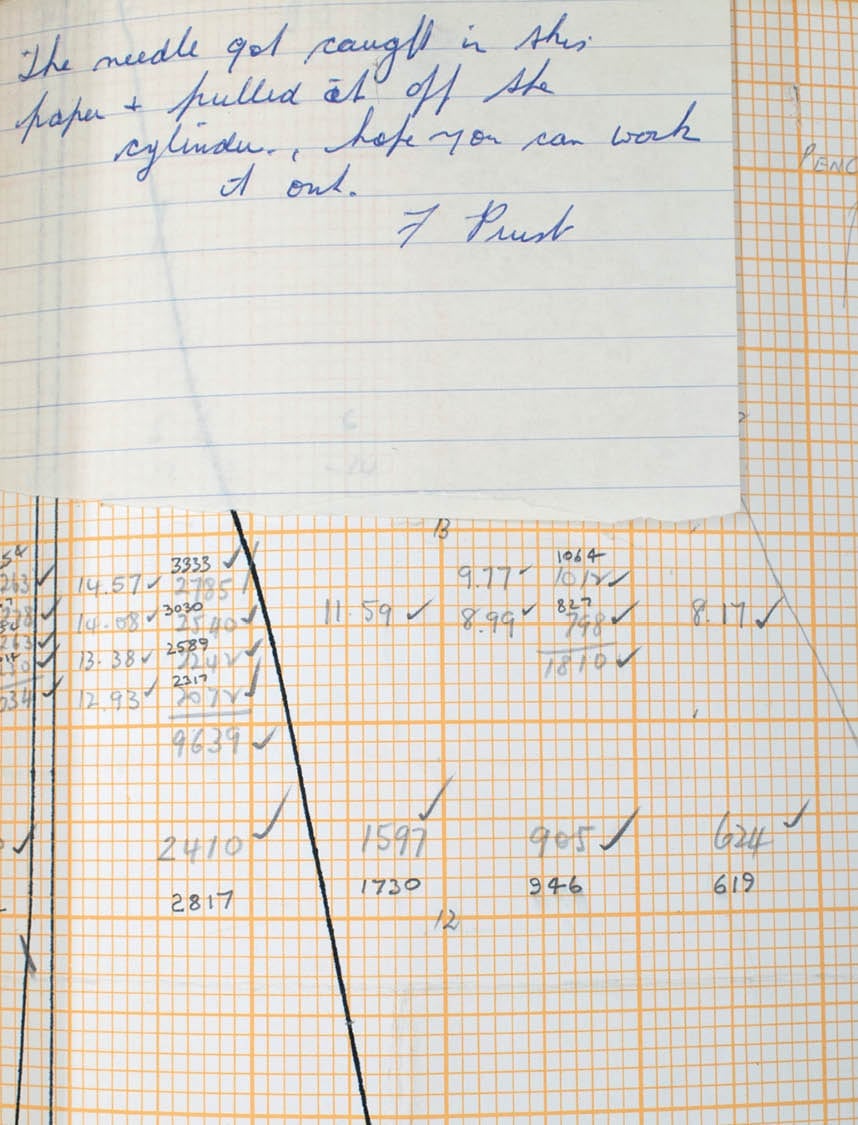

The handwritten records are not always careful, not always painstaking, not always precise. More stationery was needed. Mistakes were made, to be corrected in red or blue or green pen. Fourteen-year-old children of gauge readers took over the readings. Records went missing. The pen broke. The water dried up, or refused to be enumerated.

The river is handwritten until approximately 1993. In April of that year, a stingily pigmented grey facsimile is provided to the gauge reader with a note in pencil across the bottom of the page: ‘BILL IF YOU LIKE THIS NEW FORMAT I WILL SEND IT IN FUTURE INSTEAD OF THE OLD ORIGINAL’. By this point the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission had become the Rural Water Commission, soon to be renamed the Rural Water Corporation, which sounds bad enough, but these divisions of water culminated in mid-1994 with the privatisation of watercourse level measurement to Thiess Services (also a contract mining company).

An old original. Reproducing images of records for publication is more straightforward if the records fall under Crown copyright, that is, if they were created prior to the mid-1990s. Although copyright is defined as a type of property founded on a person’s creative skill and labour, the gauge readers – without whose creative skill and labour we would not have this history of watercourse measurement – do not own copyright. For that matter, neither do the bodies of water which provide the raw material.

- Show, in remarks column, the extreme height of all floods, that is, if greater than the height observed at the usual time of reading.

- The river knows what it is to be called an accomplice.

- The river climbs back up the mountain, quelled for now.

- Indicate days of rain by a star encased in a circle.

Q: What is the effect of the river on the gauge readers?

A: Fig. 5, 6

For nine months I worked in this archive. The job is an exhausting mix of physical and emotional labour and so talking non-productively and staying still become survival strategies. Our bodies are tired and dusty and in pain, we lean on the taped-up arms of trolleys, we smooth polyethylene sheets on our forearms to re-house brittle paper. We take pleasure in performing repetitive tasks with flagrant ease. In disobeying through perfect compliance, so subtly we are beyond reproach.

Several months in, I become convinced that certain of our conversations are only possible due to the location in the archive in which they are held. Like a symbiotic relationship or a biological co-dependence. This idea seems irrational, so I search for a topographical model to give it credence. This is a map in which the five levels of the archive are overlaid (so far, in accordance with physical reality) and there are lines like fishing wire which connect locations on each floor. Land files on Level 2 and complaints against police brutality on Level 4. Swimming pool regulations on Level 1 and architectural plans for a state-owned hotel never to be constructed on Level 3. Early divorces in churches and railway tunnel construction. The river and the eroding habitat of Victoria’s bird emblem, the Helmeted Honeyeater. The lines act as pulleys, compressing and separating the floors. These lines are invisible unless you are looking for them.

- In the river or the archive who is

it that can cease the rust, close the case.- In cross-section we pass our hands through the vertical plane, we do not fear exposition of internal structures, our thick burrows in the past. Brightness in the water, who goes by that?

Q: What was your daily routine like in those days?

A: ‘I would be glad if you could forward me some more stationery & also let me know if it is necessary to stamp all correspondence – CP.’

Q: There are, of course, gaps in the archive’s collection, and temporary spaces – vents, pipes, doors – in the building seal. Where the desire to know is totalising, failure is relief. How do you, the river, take advantage of this?

A: Float is now resting in mud (29.11.67) Battery

seems still to be flat (24.12.64)

Clock did not work, battery seems to have

gone flat (21.12.64)

Clock seems to have stopped (19.11.64)

Clock did not work (5.11.64)

Before incorporation into the archive, is this the river short-circuiting the technologies of measurement?

In an essay for Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art, Jessyca Hutchens examines the artists Christian Thompson and Julie Gough, whose work intervenes in archives of Indigenous objects held in anthropological museums: ‘instead of pulling something from the depths of the archive in order to make it accessible, these works seem to extend the archive’s surfaces, in either partial or temporary ways’. When we resist clarity, the material surfaces of the archive – what Susan Howe calls the ‘so-called insignificant visual and verbal textualities and textiles’ – might appear to us as art.

Take the cusec. The word describes a unit of measurement: the flow of water equal to one cubic metre per second. Over the course of a month, we know the maximum, minimum and mean flow for any Victorian waterway identified by the Commission as in need of rationalisation. Years of recordkeeping tell us that the mean

cusec is higher in winter than in summer for all rivers on record: January 1959 (2.2), to August 1959 (29) to January (1.3). The repetition of surfaces, of height tables and flow rates, a favoured ink or habit of calculating averages in magenta pencil on the verso of returned reports, all counter the quest to knowledge – the search for a key to all mythologies – that the state

enacts through its archives.

Q: What is the river’s place in the archive?

A: Fig. 7, 8

- Ripples on the water, and it is hard to give the exact time.

- Water around us and an hour in the airlock where the paint saponifies to many-sided crystals.

- The preservation of a usual time of reading.

- The witness evaporates after the recounting.

- The witness claims not to be inhabited by numbers, that they merely borrow bodies for passage.

- ‘I have found no evidence to suggest that velocity is to blame…’

- The river is inhabited by forces of solidification and reification!

Q: What control does the river have over the materials it is made of?

A: Fig. 9

Q: The river is remembered through the recording of certain features, such as evaporation, in the water temperature before touching and after setting, in the amount of water added or removed. What is remarkable, and therefore memorable, is difference – rainfall 16.4mm on Day Six, 0.0mm on Day Seven, and 9.6mm on Day Eight. How does the river remember, and where are its memories stored?

A: ‘But at present the river is as usual’.

- Us too, our pressing up to the past,

our obedience to hydrologists and their instruments,love for the blue grids and uncracked circles.

Q: What else is submerged?

A: ‘On Jan. 22, the gauge was seen at about five o’clock. The water was not flowing at all on that side where the gauge is as it is all blocked up with sand. I dug a drain, about a chain long, to where the water was and the water flowed into the gauge for a few days but it soon dried up. Now, all the water is flowing on the other side of the bridge. The water has not flowed into the gauge yet.’

- Below ground or above ground,

the lie keeps the real thing safe,

the sacrificial numbers, lines, charts,

colours, dates, graphs, letters, cleaved like dry wood splits for the fire and the soil.Ainslee Meredith is a poet, paper conservator and PhD candidate in cultural materials conservation at the University of Melbourne.

p. 11.

pp. 298–320.