What you are about to read is a demonstration of Ara Irititja given at the International Australian Studies Association (InASA) Conference in December 2016.1 In the darkened lecture theatre, a clip from the Ara Irititja archive is projected onto the wall. It shows old people including Rene Kulitja’s father Walter Pukutiwara performing inma at a festival in Fregon in May 1989. As the recorded sound swells, it is joined by a new voice. Rene begins to sing ‘Inma Pukara’ and dances slowly into the room.

What you are about to read is a demonstration of Ara Irititja given at the International Australian Studies Association (InASA) Conference in December 2016.1 In the darkened lecture theatre, a clip from the Ara Irititja archive is projected onto the wall. It shows old people including Rene Kulitja’s father Walter Pukutiwara performing inma at a festival in Fregon in May 1989. As the recorded sound swells, it is joined by a new voice. Rene begins to sing ‘Inma Pukara’ and dances slowly into the room.

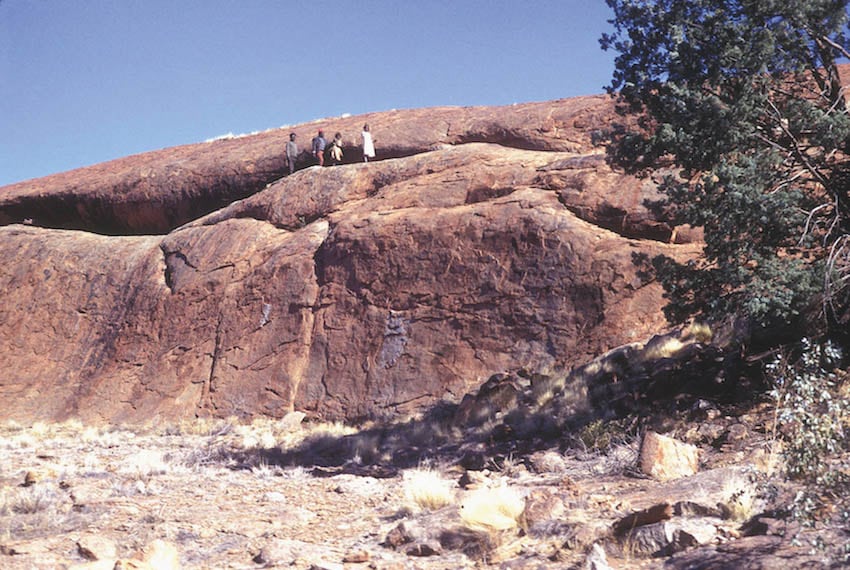

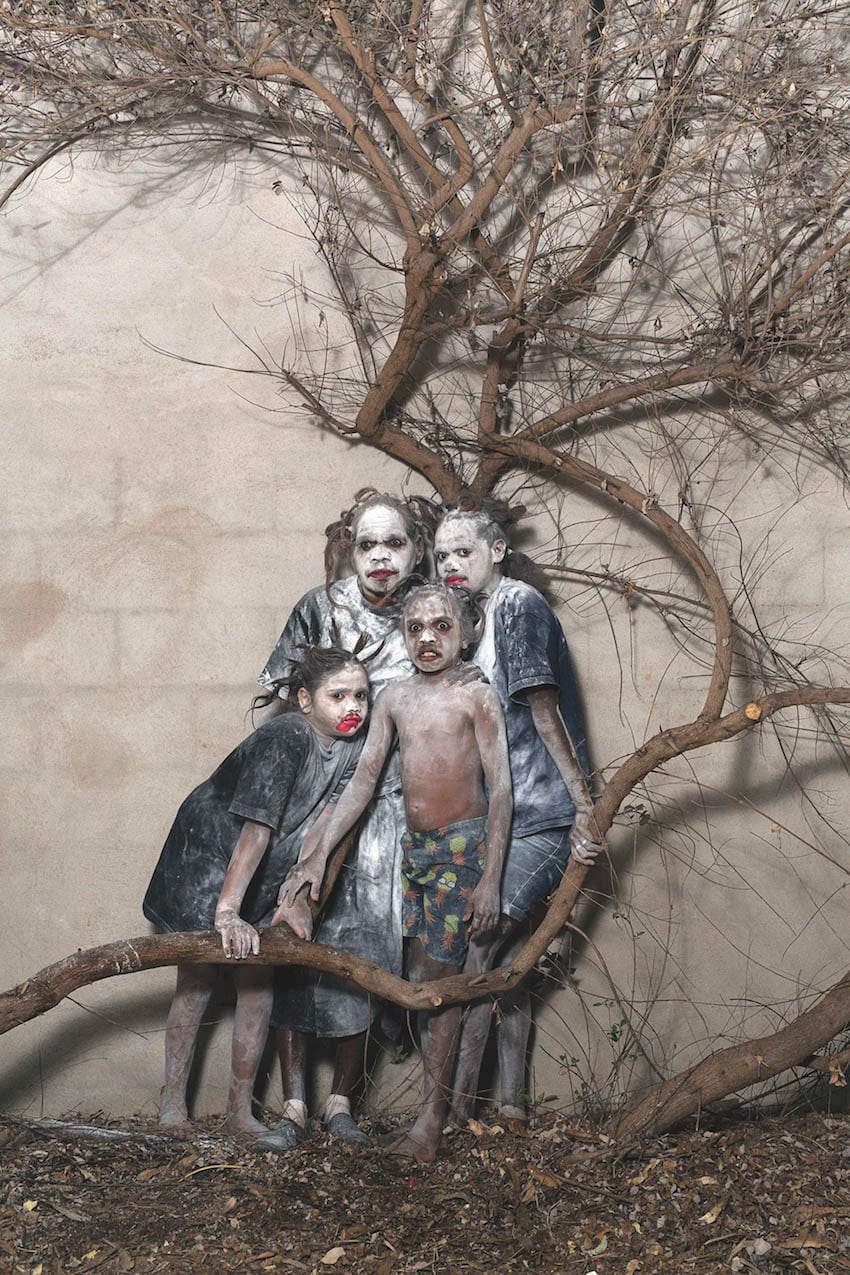

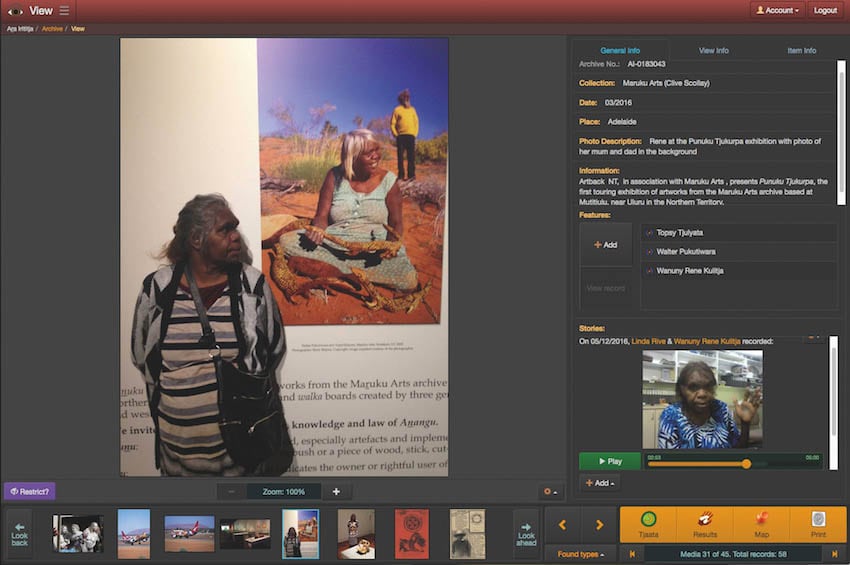

Wana katurali mirara wanala Wana katura mirara wanala Nyuntu ngalili itari katiku Nyuntu ngalili itari katiku Nyuntu ngali Itari katiku Wana katurali mirara wanala Wana katura Mirara wanala Nyuntu ngalili itari katiku Nyuntu ngalili itari katiku Nyuntu ngali Itari katiku Wana katurali mirara wanalaTranslation: We lift our digging sticks into the air and watch them rise up, You and I then drag our digging sticks along the ground behind us. Rene continues speaking in Pitjantjatatjara and Linda Rive provides the English interpretation directly after each paragraph: ‘Good afternoon. Hello everyone, what I am going to talk to you about today is Anangu tjutaku ara. That means Anangu – our people – and their traditional culture. Our way of life. My father and my mother and my grandfather and grandmother all came into Ernabella Mission for the first time as young people and children, a long time ago. Our parents later became parents themselves and had we children, and my grandparents taught them how to raise children. Life was really wonderful then. Everyone was really happy. We were all very happy people living good healthy and interesting lives, and we had good happy families. ‘My upbringing included being taught by my parents about our traditional culture and country. My father, in particular, would take us out and show us our country sites, all the places we were responsible for and where there was water [Fig.2]. The idea was that the knowledge was to be continued in future generations, that we would teach our children in turn. Not just the locations on the land but also the Tjukurpa. All of the old totemic stories, the Dreaming Ancestors, all those stories of the culture and the landscape, we were taught all of that. ‘Here is a photograph of us with our little wiltjas, the little shelters [Fig.3]. We girls were playing at being grown-ups and doing what we were going to do when we grew up. It was important for us to know how to build a wiltja, because if we walked anywhere and it started to rain heavily, we would know how to shelter ourselves. 'This archive is called Ara Irititja, because it is referring to what we are looking at – ara – stories of a way of life – and irititja – traditional. Ara Irititja means what our tjamu and kami did – what our grandfathers and grandmothers used to do. They taught about the way they used to live. All the people across the lands all had their own places, their own sites with their own songs and their own stories. After everyone came into Ernabella Mission and had been there a while, they later re-established their own homelands and reclaimed their own country and their own spaces, and we have a big record of all of these places across the lands now, on Ara Irititja, for us to remember and know. ‘Many years later, I am now an adult woman in my own right, and I have had years and years of education from my father, and he taught me so much, which now I fully understand. So now I carry on that knowledge, just as he had intended. Now I am a senior traditional owner myself, very knowledgeable and able to speak on behalf of the country. ‘I have a lot of responsibilities towards my land today, and one of the things I enjoy doing is land management work. This photo is of controlled burning. The idea of burning is to remove the heavy overburden of grasses and clear the land and make way for new shoots to come up. This is called nyarulpai which means to cause regeneration and new biodiversity to come up [Fig. 4]. ‘Because of my long education in traditional culture and knowing the songs and dances I am now a very confident dancer and singer. My relatives and I are asked to do a lot of public performances, and here is an example of us dancing to open the new Emergency Department in the Alice Springs Hospital [Fig. 5]. A lot of us women banded together and all danced towards the hospital, emulating a woman taking her sick baby to the hospital. It was a very special moment for us, only recently. ‘Another story about me knowing country and also knowing art – in the early 2000s I did quite a small painting along with 30 others. Those small paintings were sent to America. My painting was the one that was selected to decorate an airplane [Fig. 6]. The plane was painted and a large group of women and children and I went to Sydney to welcome it. The plane landed, and on it was my painting, which had been enlarged and painted all over it. We all danced to the arrival of the painting on my airplane. Not very long ago, maybe last year or just recently, we all went to Sydney again to say goodbye to the plane. The plane is now painted over or cleaned off, so we all went back to Sydney again and we said goodbye to it. We were able to touch the plane, and say goodbye, and then the plane left. You won’t be able to see it any more. But that was a beautiful occasion. I am sorry to see it go, poor thing. ‘I am also a fibre artist and I work with the Tjanpi Desert Weavers creating sculptures. I have been doing that for a long time now. It is really good fun. One of my recent sculptural installations that we made was called Kuka Irititja, which means ‘meat animals of a long time ago’ and we were referring to animals that are now extinct or at least endangered.2 They were very familiar animals to our great-grandparents, and our grandparents, who would hunt and eat them on a regular basis, but us younger people today, we have grown up never having seen these animals. But we know they once existed because we were taught all about them. is is part of our education to be taught about those earlier animals as they are part of our heritage. So all we have now are sculptural installations of these poor animals that were once upon a time very common. So we make them out of tjanpi grasses [Fig. 7]. ‘One of our very old stories is about Mamu, who are monstrous scary people that come out of holes in the ground, and as they come up out of the ground they call and sing and shout. So here we are being those Mamu as they come out of the ground calling and shouting [Fig. 8]. We painted our faces to look like scary Mamu. ‘A very important part of my story – my family’s story – is the story of Maruku, which is the wood carving arts centre for us Anangu, established by my father. is is a very important part of our heritage because we have been wood carvers since time immemorial. I am very proud of my father and my parent’s achievement for establishing this organisation. It is now a very big organisation intended for all of the woodcarvers across the three states of Northen Territory, South Australia and Western Australia to have as a central location to sell their art, their carvings and their traditional tools and implements. ‘An exhibition named Punuku Tjukurpa has been held in Perth and also Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane [Fig. 9]. It is a big retrospective exhibition of all our woodcarvings that have been held at Maruku for many, many years.3 Most of these woodcarvings in this exhibition are not mine, they are our parent’s generation’s woodcarvings, so they come from the previous generation. We have kept them especially, and now they are very important and beautiful pieces that we show people all around the world, as our older generations’ work. We have sent them to the exhibition for the rest of the world to see and appreciate. They are historical pieces now, that we have kept, and they are only for showing. These are saved pieces now, which are very special and are now getting very old. ‘My favourite picture is me, standing with a photograph of my mother and my father at the Punuku Tjukurpa exhibition [Fig. 10]. My parents were beautiful, beloved people. So it is very important to me that this image is on Ara Irititja, because these two people are my inspiration. They are my inspiration, my knowledge, my teachers, my parents and very beloved. ‘There was a lot of love in my family. My parents loved me very greatly and I loved them in return, and honour them and honour their fantastic parenting and teaching that have made me the whole woman that I am today. is is an important picture to me because it has got all three of us in the one place at the one time. is is an example of what Ara Irititja can do.4 ‘My great-grandparents and grandparents had my parents a very long time ago when they didn’t know very much about the outside world. It was then that white people arrived on their land for the very first time and my people started to learn about white peoples’ food and white peoples’ things and they tried these things and they started to move to where white people said they should go. These white people were very friendly and there are some very long-lasting friendships that have developed out of those times, and everyone was interested in each other. e white people were particularly interested in the Aboriginal people that had come out the desert, that they were becoming friendly with, and so they started to photograph them. And so photographs were taken of my people at all sorts of times of the day and the night, of them laughing and eating food and doing things, and looking. Not that my people actually knew what was going on, but we know now that a lot of photographs had been taken of them. So what happened to all those photographs? Well, they ended up – a lot of them ended up in museums. They ended up in different places. We never saw them, but they ended up somewhere. They were somewhere. ‘After my people came into Ernabella Mission they started to learn about the outside world and they started to get the hang of things and they started to understand what a photograph was, and what was happening. They are all coming back to us now, and these photographs are here now on Ara Irititja. ‘Even collections of moving images are finding their way back to us. Ara Irititja is searching and finding and getting them and putting them up there. So now people who speak Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara, Pintupi Luritja, they can all look at these pictures of themselves in this one big archive called Ara Irititja. Anything we would like to see about our own lives, we can see here on our archive Ara Irititja. 'We want Ara Irititja to last forever. We want our children and their children and their children and their children into the future to be active on Ara Irititja, to be able to see Ara Irititja, to know about it and to use it. ‘When photographs are taken of us, we don’t want them to vanish into a museum, to disappear and be unable for us to see them. We don’t want that. We want images of us to come back to us, to be repatriated to us, through our one-stop-shop called Ara Irititja. In this way we can engage our children and teach them about their cultural heritage in a new way, through our own archive. It is one really good way to do it. ‘So it is really brilliant, and I am so proud to be telling you all about Ara Irititja today, I am very happy to be able to speak my own language and happy for you to know that I really love Ara Irititja. I am so proud of it. It is so wonderful, because it has got everything in it. Our country, our land, our people. ere are pictures, there are movies. Ara Irititja has everything. Thank you.’

Applause

John Dallwitz responds to Rene’s speech by first turning to the audience: ‘So now you know what a responsibility we have’. He then turns to Rene and Linda who have been speaking together on stage: ‘Thank you both for that presentation. To be able to hear that what I have been doing for twenty-five years is great and that it is appreciated and used, I can’t think of anything more rewarding. ‘The first introduction for me to bring the photos back into the land of the people for them to see was of Rene’s mother and father who were just the most amazing people, and that was in 1991 for the tenth anniversary of Land Rights. So I created an exhibition of twenty aluminium panels with photographs of Don Dunstan and Rene’s parents and other friends and associates who had all marched in the streets for Land Rights [Fig. 11]. And as the exhibition was going up, a team of people behind me were watching and waiting for the next panel. They were pulling them out even before I could hang them up, because they wanted to see these photographs. I knew then that this was something I had to do, and it wasn’t just this exhibition. ‘About 3pm in the afternoon, this huge brown cloud started to come towards us, and I was asking, “What’s going on?”! ‘They said, “This is a storm. We had better pack up.” So we grabbed all these panels, ripped them off the walls, shoved them in the back of the four-wheel drive, and this great big cloud came through the skies and then it began to rain [Fig. 12]. It rained and rained, and we just managed to get ourselves into the vehicle. It was four o’clock in the afternoon, but it was pitch black. All we could see of the landscape was it being lit up by lightning. It was a pretty memorable day, and it was really the beginning of me realising how important these photos were, and getting a bit of a taste of what the conditions were going to be like to work in for the next twenty-five years.’ Susan Lowish: ‘The thing about archives is that they are not only documents in institutions, or files in a computer, but they are also deeply personal, for subject, creator and audience; they are sources of pride, celebration and happiness. Ramesh Srinivasan suggests that technological systems can be used to reinforce structures of power, but they can also enable culturally and newly focused goals.5 We have seen the empowering potential of a culturally-centered knowledge management system and the possibilities it holds for bringing together fragments of narrative, photographs and artworks and how Anangu with Ara Irititja present them in new and meaningful ways. ‘Harald Prins warns that “the current relief from visual imperialism afforded to Indigenous peoples by the web [or by digitized archives] may be phantasmagoric and the ‘visual performative’ alone will not overturn their subaltern positions in the political arena”.6 Prins calls for Indigenous communities to develop media that cannot be incorporated or absorbed by imperialistic influences. Looking again to Srinivasan, “the challenge is clear: communities must push to develop new media and information systems that are not just exhibitions or aggregations of content, but also are built around locally and culturally specific representations and paradigms.”7 ‘Anangu with Ara Irititja exceed this challenge. They not only create content but are also architects of the system and drivers of re-presenting material in contemporary contexts. By performing inma alongside the archival footage of her father, Rene brought the historical material into the present and gave it new life. She also reminded us of the important work of archives and the people who devote their lives to them. It is very clear that families are far more significant audiences than academic conference goers or public program attendees. Anangu also don’t need researchers to tell them that there are positive links between good health, well-being and access to their own cultural and historical information. Indeed, they have answered Anne McGrath’s question “Is history good medicine?”’.8Rene Kulitja is an important artist, community leader, Pitjantjatjara Elder and Director of the NPY Women’s Council. Founding director of Walkatjara Art Centre and former chairperson of Maruku Arts. Rene’s work has been exhibited across Australia, Europe and Asia. Linda Rive has spent thirty- eight years working with Anangu, as their interpreter and translator. For the past ten years she has focused on recording oral histories and cultural knowledge for their own digital archive, Ara Irititja. John Dallwitz is Coordinator Ara Irititja Project, the community-owned, multimedia digital archive, developed over twenty-five years ago at the request of Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara (Anangu) communities. Susan Lowish lectures in art history at the University of Melbourne, and introduces students to ‘remote’ art centres of Australia.

1. For more, please visit: http://www.irititja.com

4. For another example of what Ara Irititja can do, see: Janet Inyika, John Dallwitz, Susan Lowish and Linda Rive, ‘“Our art, our way”: Towards an Anangu art history with Ara Irititja’, in The Archival turn in Australian Aboriginal art, (eds.) Darren Jorgensen and Ian McLean. UWA Publishing, Perth, WA, 2017, pp. 151-170.

5. Ramesh Srinivasan, ‘Indigenous, Ethnic, and Cultural Articulations of New Media’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol 9, no. 4 https://es- cholarship.org/uc/item/40p4k54t

6. Harald Prins, ‘Visual Media and the Primitivism Perplex: Colonial Fantasies, Indigenous Imagination, and Advocacy in North America’, in F. Ginsburg, L. Abu-Lughod and B. Larkin (eds) Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2002.

7. Srinivasan, ‘Indigenous, Ethnic, and Cultural’, n.p.

[^8]: Anne McGrath, ‘Is history good medicine?’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 38, no. 4, 2014, pp. v396-414.