Between the subjugation and indifference of colonial governance, Ngurungaeta, William Barak leads the Wurundjeri people in a sustained decolonising movement, seeking land-rights at Coranderrk. They petition ministers, writing letters and walking to Melbourne to protest directly to the Premier. is goes on in the face of dispossession. And, in 1881 there is a rupture in colonial history, when their claims to justice are addressed at the 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry.1 This, the last moment to contest an eviction from Coranderrk, is a part of ongoing resistance to the ontological violence perpetrated by a colonising state and its individual agents.

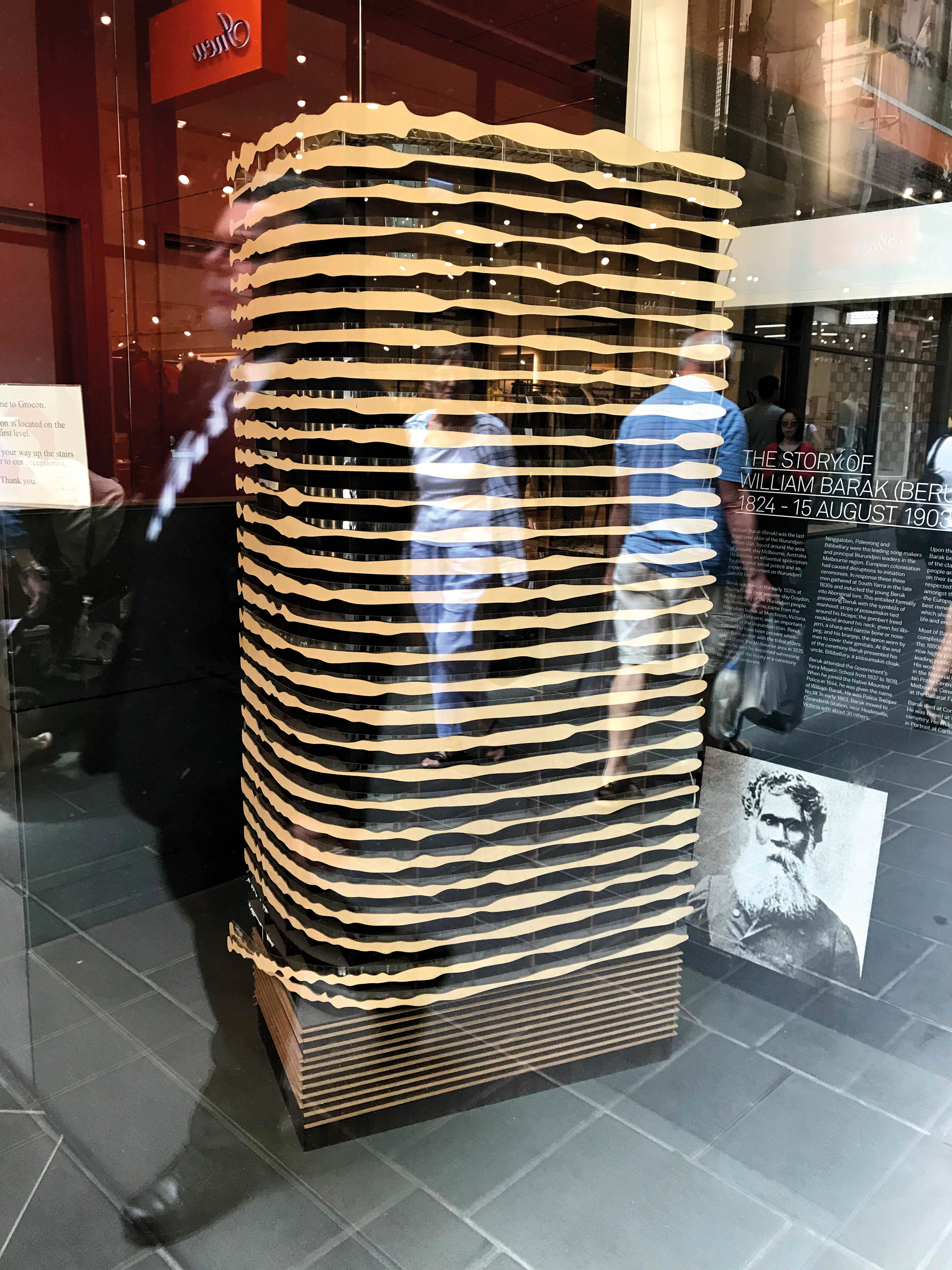

In 2015, architecture firm ARM erected a thirty-two-storey apartment building to monumentalise Barak in the cityspace known inter alia as Melbourne. Financed by Grocon, this building was named Portrait and white striated panels were fixed to the balconies at each of its thirty-two levels. Negative spaces between each panel, if viewed only from a particular angle and at a distance, meld into a giant image of Barak’s visage. This display of inhabitance functions like macular degeneration to habituate the senses to colonial presence and corporate desires. Devoid of depth and sincerity, Portrait is a form of memorialisation that is more about forgetting than remembering. It reduces Barak, a significant proponent of decolonisation, to a form of new Aboriginal kitsch.

New Aboriginal kitsch is an accommodating face, a stratagem that exemplifies the disjuncture between the objectives behind decolonising talk and the talk’s material consequences. In bad taste, the impetus of new Aboriginal kitsch – prima facie decolonising act – is to legitimise colonisation while syphoning power from Aboriginal cultural forms. The all-too-seen becomes the not seen at all,2 enabling the forgetting of actual Aboriginal people and the forgetting of that forgetting.3 Recent partnerships between ‘socially conscious’ local arts organisations and architecture rms (like Gertrude Contemporary’s collaborations with Sibling and Edition Office), enact a similar logic of deflection. They erect glistening, mirrored facades that shroud gentrification, social rinsing, and displacement, while at the same time inviting fetishistic adherence, fabricating a ect without substance.

A towering figure, Portrait insists that sight is the body’s primary mode of knowing. On the outside of the building, ninety-six black and silver domes spell out ‘Wurundjeri I am who I am’ in braille, but the massive scale negates this tactile writing system by making it purely visual, instead revealing an ocularcentric desire to suppress other senses and neutralise bodies. Sheer roller blinds fitted at every window of Portrait are the taupe tentacles of this highly controlled visual regime, giving occupants a semblance of control over space they believe to be their own and over the composition of Barak’s visage.

Several Wurundjeri Elders were involved in the consultation process with ARM, granting permission to reproduce Barak’s image. Wurundjeri Elder, and great-granddaughter of Barak, Aunty Doreen Garvey-Wandin articulated the lively significance of Barak’s image as an overt (re)statement of the Aboriginal presence in Narrm: ‘Something like this has been a long time waiting, and I think it’s wonderful’.4 Yet, Portrait is also illustrative of an architectural attitude that fails to take seriously phenomenologically grounded approaches to creating spatial experiences; the relationships between bodies, the environment and the machinery of inhabitance.

The consultation of the Wurundjeri Elders was limited to the authorisation of Barak’s image and not the architecture of the building. Portrait stands in opposition to Indigenous ways of being-in the world. The finished building is a representation of Barak that fails to question how Barak himself would read the building’s presence or ARM and Grocon’s desire to make money off colonial occupation. Rather than acknowledge the significance of what Barak accomplished in his life or the land-rights of living Wurundjeri peoples – the land Portrait occupies – Barak’s image is reconstituted as new Aboriginal kitsch, drained of its significance and used to disguise an exclusionary building as just the opposite: inclusive, egalitarian and part of a cultural topography.

While earlier forms of Aboriginal kitsch – racist picanniny dolls, ashtrays, mugs and so on – can be read as ironic and re-appropriated to subvert economies of racism, new Aboriginal kitsch attempts to provide all answers in advance in order to preclude aesthetic and ethical criticisms.5 Portrait rejects irony to coerce the viewer into taking a thirty-two-storey bodiless head as a decolonising or, at least reconciliatory, act. It sensationalises Barak’s image, in order to distort ethical or aesthetic accountability. While artefacts of earlier kitsch are ironic caricatures of settler-colonial anxiety, new Aboriginal kitsch caricatures decolonising movements and Aboriginal peoples.

Craftier than producers of earlier kitsch, producers of new Aboriginal kitsch position themselves as socially minded, decolonising agents. New Aboriginal kitsch mimics characteristics of decolonisation in an attempt to fool people into celebrating colonising forces, by making them think they are celebrating decolonising forces. It dislocates the ethical component of the formative action from the aesthetic, reaching for pure affect. However, new Aboriginal kitsch doesn’t simply reach for the superficial, rather what is at stake is its imitation of the formal characteristics of decolonisation so as to distort its underlying forces, like capital accumulation, gentrification and colonisation, which stifle decolonisation. Portrait uses Barak’s image as a veil, exemplifying how New Aboriginal kitsch is devised to make people ‘innocent of their complicity’ in colonising processes.6

While Portrait effaces the legacy of Barak’s commitment to Aboriginal land rights in its full- frontal address, several suburbs away in Preston, the new Gertrude Contemporary space turns its back to the street. Designed by architecture firm Edition Office, the facade of the not-for-pro t arts institution’s new gallery bears a woody grin of exposed wall studs as decorative element. Those who enter Gertrude’s new space venturing past its fetishisation of low-cost building vernacular have their concerns subjugated to things like sight lines, further architectural affectation, engineered homogeneity. The gallery and its new architecture can be understood in the same way as all the (social) media that frame it, a mechanism of representation in its own right.

The similarity between the military minimalism of contemporary apartment buildings and the architectures of the gallery is not coincidental. Both deploy universalising technologies (climate control, fixed windows), intended to render a body ghost-like, a spectral organ of cognition for the bodiless appreciation of art. Just as towering apartment buildings encroach on suburbs, enumerating sterile white cubes, at the frontline of gentrification are the white cubes of art galleries. Hiding behind them are property developers who deploy these phenomenologies of artwashing to provide a shiny, o en ostensibly community-engaging veneer that masks the accumulation of capital by displacement.

Gertrude Contemporary is one case in a recent spate of collaboration between arts organisations and architecture firms in Melbourne; others included are Gertrude Glasshouse and Sibling, Utopian Slumps and Neometro. While these arts organisations are more inclined than Grocon or ARM to take part in decolonising chatter7 in their programming, they edify similar colonising tendencies – settlement, displacement and resource exploitation – in the processes of gentrification. The inclusion of artists and curators who, though they may legitimately maintain a decolonising practice themselves, perhaps even surreptitiously critiquing the gallery, are incorporated into programs to obscure the colonial and gentrifying practices that the gallery is complicit in. This type of decolonising chatter is typically directed at forces that can be located outside the gallery rather than addressing how the existence of the gallery is dependent on these very forces.

Before moving to its own vanity toponym, ‘Preston South’, Gertrude Contemporary occupied a large property (formerly a textiles factory) on Gertrude St in Melbourne’s inner-city suburb Fitzroy for thirty-two years. Gertrude Contemporary’s renaming of territory (Preston South) as they entered it is part of a marketing strategy used to promote the new premises. Not only is renaming sine qua non for colonisation, it is a popular strategy deployed to increase the monetary value of property. A press release made by the gallery for the opening of the new space announces:

Located right on the main High Street strip, the area is a wonderful new home for Gertrude and our audiences. It is a vibrant and developing hub of great food, bars and interesting shops and is highly accessible by public transport – tram, train and bus alike. We are creating a “Gertrude’s Guide” to the new area highlighting some of our favourite places in the area.8

Gertrude Contemporary’s Guide is reminiscent of a colonising process of mapping, whereby the topography of the land is flattened (literally and figuratively) to create an empty, categorised space ready for occupation.

New Aboriginal kitsch is crafted to disguise its purpose through its form. Like the gasps of shadows that Portrait uses to compose Barak’s visage, it’s a mutable presentation of Aboriginality deployed to exclude the impossibility of living ethically as a colonising agent from the purview of colonising acts. New Aboriginal kitsch is an operant that produces willing participants, innocent of their participation in the forces that they would likely disavow. Aboriginality and decolonising are inverted as marketable resources – forms of ‘authentic’ cultural capital used to legitimise colonial presence.

Tristen Harwood is an Indigenous writer, cultural critic and independent researcher, a descendent of Numbulwar where the Rose River opens onto the Gulf of Carpentaria. He lives and works in the Northern Territory and Naarm.

Lauren Burrow is an artist based in Melbourne.

[http://www.gertrude.org.au/ exhibitions/gallery-11/past-14/ octopus-9--i-forget-to-forget.phps](http://www.gertrude.org.au/ exhibitions/gallery-11/past-14/ octopus-9--i-forget-to-forget.phps)